# RNA-Seq Differential Expression Analysis Day 1

**When:** Monday, June 21st & June 23rd from 9:30 am-11:30 am PDT

**Instructors:** Amanda Charbonneau and Saranya Canchi

**Moderator:** Marisa Lim

**Helpers:** Abhijna Parigi, Jeremy Walter

**Zoom:** https://zoom.us/j/7575820324?pwd=d2UyMEhYZGNiV3kyUFpUL1EwQmthQT09

:::success

While we wait to get started --

1. Click this button [](https://binder.pangeo.io/v2/gh/nih-cfde/rnaseq-in-the-cloud/stable?urlpath=rstudio) to start a virtual machine. It can take up to 20 minutes for them all to start with this many participants so we're going start them and talk about the differential expression (DE) pipeline we're using while they all spin up.

3. :heavy_check_mark: Have you looked at the [pre-workshop resources page](https://github.com/nih-cfde/training-and-engagement/wiki/Resources-for-Workshop-Attendees)?

2. :pencil: Please fill out our pre-workshop survey if you have not already done so! Link here: https://forms.gle/4jGFeV7eJpV3exhD6

Put up a :hand: on Zoom when you've *clicked* the launch binder link! (It takes a few minutes to load, so we're getting it started before the hands-on activities)

:::

[toc]

# Introductions

Have you heard of the NIH Common Fund Data Ecosystem?

:::success

Put up a :heavy_check_mark: for yes and a :negative_squared_cross_mark: for no!

:::

We are both postdocs at UC Davis and part of the training and engagement team for the [NIH Common Fund Data Ecosystem](https://nih-cfde.org/), a project supported by the NIH to increase data reuse and cloud computing for biomedical research.

You can contact us at achar@ucdavis.edu and srcanchi@ucdavis.edu.

Links to papers we mention and other useful references are here:

https://hackmd.io/vxZ-4b-SSE69d2kxG7D93w

# Conceptual Overview

::: info

## Learning Objectives:

- Run a RNA-Seq pipeline

- Learn the basics of the pipeline elements and how to run them

- Learn what some basic RNA-Seq files look like

- Learn how to make your own analysis reproducible

:::

This is a two day workshop. Over the two days we're going to go through an entire RNA-Seq pipeline. Today we're going to do the prep part of the pipeline: cleaning, aligning and getting counts. On day two we'll put that data into R and do a differential expression analysis. This is a very short course that is meant to be an overview of a pipeline, and the material is a compressed version of other ~8-16 hour courses I teach on RNA-Seq. So, for many steps I've included links out to more materials with more detail in case you'd like to explore further.

----

If you attended the RNA-Seq concepts course, you might remember [this figure](https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-020-76881-x/figures/1):

from [a paper published last year](http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-76881-x) where they ran the same two datasets through 192 different pipelines to see how the pipelines changed the results. The pipeline we're going to use is **Trimmomatic -> Salmon -> TPM -> DESeq2**:

The concepts workshop covered a lot of experimental design and the conceptual mathmatics behind differenetial expression algorithims, but we mostly glossed over choosing a pipeline, so why did we choose this pipeline today?

- It's relatively fast

- It uses popular tools

- The tools have active developers

- I know it pretty well

Those all probably sound like really bad reasons, but they actually aren't. Fast is good for a very short workshop, but if you have a good experimental design, data with at least 3 (but prefereably more) biological samples per modeled treatment, have done a 'standard' experiment (so you don't expect only one genes expression to have changed, or every genes expression to have changed) and have a transciptome to map to, this pipeline is likely one you would choose. It uses popular tools, which also means these tools are the ones with the most people using them and finding and reporting bugs. All those users also means that the there are also lots of people asking for help making the tools work with their edge cases. These widely used tools are among the most flexible because so many people use them! It's also important to keep in mind that with a differential expression analysis:

- You are always measuring biological variation plus a whole bunch of experimental variation

- There are no techniques for empirically measuring what the biologial levels of any given RNA transcript are in a cell- qPCR is good, but it's still PCR. Random sampling is *inherent to RNA-Seq assays*.

- We can say that one pipeline gives more or fewer DE genes, but which one *best reflects the biology* is not really known. When most people compare pipelines they are looking for the one with the *most* DE genes...but more DE genes isn't necessarily better, it's just more. What is expected for *your* experiment?

- The best we can do is to understand the assumptions and constraints of the pipeline we use, and if our data doesn't fit those parameters, choose a pipeline that is a better fit

The good news is that all of these pipeline choices start at having reads! If you have done a good job with your experimental design, and find that your data isn't a perfect fit for your pipeline, it is easy to change to a new pipeline. A good RNA-Seq dataset can be run through *all* of the pipelines described in [Corchete, et. al.](http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-76881-x). An experiment with poor experimental design won't work in *any* of them.

:question: Questions?

:::success

:heavy_check_mark: Did the binder load? Put up a :hand: on Zoom if you see Rstudio in your web browser. There is another long loading step that we can run while we chat. Once your binder has loaded open the `terminal` tab and paste in these commands:

```

conda init

echo "PS1='\w $ '" >> .bashrc

source .bashrc

conda env create -f rnaseq-env.yml

```

We'll talk about what they do in a bit

:::

---

## Getting and caring for your data

Typically you will give your prepared cDNA to a sequencing center, either as a prepared library ready to go in the sequencer, or as partially prepped cDNA that they process into a library and then sequence. Some labs have miSeqs which are small sequencing machines that are cheap enough to have in the lab, in that case you might be doing your own library prep and seqencing run. Note that miSeqs can only run a single lane at a time so may cause batch effects if you need to run a lot of samples. If you want to know more about batch effects and making sure your sequecing will result in useable data, come to our next RNA-Seq Concepts training.

If you sent out your sequencing, you will likely get an email when it is done. The email typically contains a link to an FTP server where you can go download your results. Sequencing results are far too large to send by email, so you need to go to their server and retreive them.

It's really important that you go retreive your reads, at least breifly look at them, and store them somewhere safe right away. Most sequencing facilities only retain your reads for ~ 30-60 days, and then delete the data. Most also will only re-run bad samples if you tell them within a couple weeks of recieving the data. These facilities have limited server space for data AND limited freezer space for storing the extra from your run. If you don't notice you have the wrong files, or bad data, or a corrupted file until six months later, there's nothing they can do, you'd need to redo all your samples and send (and pay for) them to be sequenced again.

When you get your data you should have two types of files, one should be a text file or an excel file that has the metadata about your sequencing. It will look something like this:

The other type of file you'll get is the sequencing data itself. This will almost always be FASTQ files, although they might be compressed when you first download them and so be `.gzip` or `.zip` or `.tar`.

## Assessing read quality

You can think of an Illumina sequencing reaction as very fancy but very slow PCR. Because the machine adds bases one at a time and takes a photograph to determine what bases are added, there are many ways in which a given base call can be less trustworthy than another.

For instance, if many clusters in the same region on a lane happen to have the same base at the same time, they can drown out nearby bases:

We're going to assess read quality today with fastQC.

## Trimming your reads

We're going to use a piece of software called Trimmomatic. You trim your reads to remove low quality bases, but even if all of your reads are high quality you still should trim.

image from https://seekdeep.brown.edu/illumina_paired_info.html

Each read will have not only the target sequence- the actual cDNA that you are interested in, but also adaptor sequence (purple) and a barcode (orange). If you have opted for paired end sequencing, both ends of the read will have these sequences. For single end sequencing, both ends will have an adaptor, but only the begining will have a barcode. In some applications (like mapping) having a bit of adaptor left over on the ends of a read is not a huge problem, but if you are asssembling your own transcriptome or genome, bits of adaptor can act like 'sticky ends' and give you poor assembly.

## Mapping

When you create a RNA library, you break your collected RNA into smaller pieces before adding adaptors:

In order to say how many of your sequencing fragments belong to a given gene, you need to map them to a genome or transcriptome. In many pipelines, mapping and counting are seperate steps:

In which case you would map to a genome or transcriptome:

But we're using a pseudoalignment tool today: Salmon. Note that Salmon is designed for doing pseudoalignments of RNA reads to a transcriptome. It will let you put in a genome for mapping (it can't tell the difference, they're all just fastas files!) but the results will not make any sense!

One of the novel and innovative features of Salmon is its ability to accurately quantify transcripts without having previously aligned the reads using its fast, built-in selective-alignment mapping algorithm. It will do the mapping-like step and counting all from one command. Further details about the selective alignment algorithm can be found [here](https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/657874v1).

## Counting

For DE RNA-Seq, we have sequenced the samples so we can measure the differences in gene expression products and compare them. However, in order to make that measurement, we had to alter the sample a number of times, and we have ended up with a file of millions of reads, each of which is only a tiny piece of any given expression product.

From https://osf.io/bv85u/

In the previous step we mapped those reads to try to determine which trancsript each came from, but for the measurement to be useful we need to count how many fragments mapped to each transcript.

from http://arxiv.org/abs/1303.2411

It seems from graphics like the one above this should be a reasonably straightforward process, but in fact, counting and how you do it can profoundly change the results of your experiment. Consider this simplified example:

Let's assume that in the actual cell we sampled, there were two genes that were expressed at exactly the same level, here I've given them a true expression level of 3 copies per cell:

For this example, lets ignore all of the possible sources of error from library prep and sequencing. Let's also pretend that when we broke these transcription products into fragments, they all broke into exactly equal, non-overlapping pieces like this:

If we perfectly mapped all these pieces back to the correct transcript and just counted how many sequences we got for each gene what would we get?

It would look like Gene A had much, much higher expression, even though, in the cell, both genes were expressed equally. This example is extremely simple and makes a lot of assumptions, but it gives us a way to visualize the difficulty of counting reads. Imagine for a moment how much more complicated this is when you have to also account for most genes having multiple isoforms, each of which is a different size:

and that we need to compare the totality of those isoforms to other genes that also have many isoforms:

And we need to do this counting in a less than perfect environment, because we know that our tool for measurement - RNA-Seq - is sampling the true cellular expression in ways that introduce bias and error.

The Salmon "pipeline" that runs when you invoke Salmon is doing its best to account for all of these different sources of bias and error using a lot of fairly complex math:

## Differential Expression

Once we have counts, we need to decide whether the samples we are testing differ by those counts. Again, this seems like it should be a simple case of comparing counts per gene, but in reality it requires a lot of careful statistical modeling to get a reliable answer.

In this tutorial we're using DESeq2 to model our counts and determine which genes are differentially expressed. Like Salmon, DESeq2 is doing a pipeline of many steps when you invoke it:

From https://osf.io/gbjhn/

Salmon has already given us counts that have accounted for a number of technical sources of bias and error. The steps in DESeq2 are largely about accounting for bias and error due to the biology itself. Your experiment won't be sequencing one individual as a control and one individual as a treatment to compare, you'll have sampled many individuals from both groups, and perhaps had more than one treatement variable. Just as you wouldn't expect any two controls to grow to exactly the same size, or at exactly the same rate, or have any other phenotype perfectly in sync, we wouldn't expect two controls to have exactly the same number of copies of each gene at a given time- even if they're clones. DESeq runs all these steps to try to distinguish the biological variation within treatment groups from the variation due to your experimental intervention, as well as removing things like blocking effects.

---

# Let's get started!

:::success

:heavy_check_mark: Did the binder load? Put up a :hand: on Zoom if you see Rstudio in your web browser.

:::

The button you clicked at the beginning of class opened a thing called a Binder. This is a cloud machine that was created when you pushed the button, and all the time we were waiting was it starting up the machine, and then installing all of the tools and data we're going to use today. Binders are great for teaching, because they let us all work in exactly the same environment and they give each of us a cloud machine for free! However, because they are free, they are relatively small and slow, so they are not good for doing a very large data analysis.

To do a bigger analysis in the cloud, you would probably want to rent a machine from Amazon or Google. These typically cost money, and don't come with software pre-installed. For this tutorial you don't need to download and install anything, but we're giving you the commands you would use here. You can set up an Amazon or other paid cloud service and use the same tools we use today. If you want to learn more about setting up a cloud computer for larger analyses, sign up for one of our [Intro to AWS workshops](https://www.nih-cfde.org/events/cfde-training-workshop-2/).

---

==Instructor Switch!==

# Running the workflow

## Setting up your workspace

Use `workshop_commands.sh` file and show people where that script can be found.

Setup the conda installer and initialize the settings:

```bash=1

conda init

```

We will shorten command prompt to `$`:

```bash=2

echo "PS1='\w $ '" >> .bashrc

```

Update your terminal to let the changes take place:

```bash=3

source .bashrc

```

:::info

Note: you could also restart the terminal for the same effect

by typing `exit` and then opening a new terminal.

:::

:::success

:heavy_check_mark: Put up a :hand: on Zoom when you've got a new terminal window and see this at the prompt:

`~ $`

:::

Create a conda environment from the provided YAML file:

```bash=4

conda env create -f rnaseq-env.yml

```

:::info

Alternatively, use `mamba` for faster installation:

```

mamba env create -f rnaseq-env.yml

```

:::

Activate your new conda environment

```bash=5

conda activate rnaseq-qc-map

```

:::success

:heavy_check_mark: Put up a :hand: on Zoom when you've got a new terminal window and see this at the prompt:

`(rnaseq-qc-map) ~ $`

:::

---

## Directory setup

A best practice for any bioinformatics project is to keep your data organized. It's easier to work if all of your data is arranged in folders (directories), and many of the tools we're going to use make several files, and it can be difficult to track which files are which. Organizing your project and using naming schemes will make it easier to do your work AND much easier to figure out what you did later. Lets set up our directory structure:

1. Make a folder for the project we're working on:

```bash=1

mkdir myproject

```

In your real work, give your project folder an informative name! I usually use something like 08_07_21_deseq_burbot so that I know from a glance when I ran this pipeline, roughly why, and on what species.

2. Make a folder inside of it for your raw data:

```bash=2

mkdir myproject/raw_data

```

It's always best to keep your raw data in it's own folder.

3. Make a folder for the reference files we'll need:

```bash=3

mkdir myproject/ref_files

```

This is where I put things that are like raw data, but that are easy to re-download

4. Make a folder for your raw fastqc output:

```bash=4

mkdir myproject/raw_data/fastqc

```

5. another for holding trimmed data:

```bash=5

mkdir myproject/trimmed

```

6. a folder inside the trimmed directory to hold trimmed fastqc output:

```bash=6

mkdir myproject/trimmed/fastqc

```

7. one last folder to hold our salmon results:

```bash=7

mkdir myproject/quant

```

8. Use the tree command to view your work:

```bash=8

tree myproject/

```

This should give you a directory structure that looks like this:

:::success

:heavy_check_mark: Put up a :hand: on Zoom when you have verified you have 6 directories with this structure

:::

----

## Download

Now let's download some files to work on. We're using a tool called `curl`. You are supposed to read `curl` as "See URL", as in, go look at a website. This means that it's default is to go look at a URL and display it to you. It does not save anything by default. If you want to keep the output, you need to tell `curl` not just where to go *look* but also where to save the output with the `-o`

:::info

The other common tool for getting data is `wget`, which you are supposed to read as 'web get'. It's default is to *not* show you the result and instead to just download (get) the URL, if you wanted it to show you the URL you'd have to give it a flag. Some operating systems have one, some have the other, hardly any have both. So it's kind of nice that you can tell their default behavior from their pun names.

:::

First we want some sequencing data. This is a public dataset from sequencing a yeast, but yours would be copying your saved data from your sequencing facility:

```bash=1

curl -L https://osf.io/5daup/download -o myproject/raw_data/ERR458493.fq.gz

```

We also want the metadata file that goes with this sequencing:

```bash=2

curl -L https://osf.io/9c5jz/download -o myproject/raw_data/err_md5sum.txt

```

We'll also need to get the files from Illumina that describe the primer sequences that were added onto the cDNA for sequencing. This sequencing run used the "TruSeq2" primer set, and single end sequencing.

```bash=3

curl -L https://raw.githubusercontent.com/timflutre/trimmomatic/master/adapters/TruSeq2-SE.fa -o myproject/ref_files/TruSeq2-SE.fa

```

We will also need the transcriptome for *Saccharomyces cerevisiae*. We're doing quasi-mapping, but that still requires a transcriptome to quasi-map to. For this workshop we have included the reference files in the `yeast_ref` folder, but are including the command to download the file:

```bash=4

curl -L ftp://ftp.ensembl.org/pub/release-99/fasta/saccharomyces_cerevisiae/cdna/Saccharomyces_cerevisiae.R64-1-1.cdna.all.fa.gz -o myproject/ref_files/Saccharomyces_cerevisiae.R64-1-1.cdna.all.fa.gz

```

:::success

### Exercise :writing_hand:

Use the tree command to determine if you have downloaded the correct files to the correct directories.

Note that the first two files are in raw_data, but the second two are in ref_files. Why?

Put up a :hand: on Zoom when you have visualized your new files and their locations.

:::spoiler Hint!

```bash=1

tree myproject/

```

Our raw data are the same kind of data, we've mostly downloaded FASTQ files, but they are fundamentally different in how we use them and how hard they are to get again if we ruin one. Its best to keep your raw files away from ones you might edit or change.

:::

---

## Validation

These files were small, so it's unlikely we had internet drop out that would cause them to be corrupted, but it's always good to check. For files that are readily available like the primers, the worst that can happen is your pipeline stops because it encounters an error and you have to start the pipeline over. But it's absolutely *critical* to check your own sequencing files when you get them from the sequencing facility. If you download them with an error and don't notice for a few weeks, you'll likely have to pay to have them resequenced, assuming you have enough sample left to send them.

When your facility emails you they'll provide not only a link to the files to download but an md5 hashsum and other metadata. The md5 hashsum is basically the result of taking each file and running it through an equation to get a short-ish number value 'answer' for it. If you run the same file through an md5 algorithm, you always get exactly the same result. If you change the file at all, it changes the md5 hash you get out of the equation. This makes it great for checking to see if the file you downloaded matches the one on the server.

```bash=1

md5sum myproject/raw_data/ERR458493.fq.gz

```

Let's compare that to the md5 sum we got from the sequencing facility by looking at the metadata file we downloaded:

```bash=2

head -n 1 myproject/raw_data/err_md5sum.txt

```

Note that you can use the first 7-8 characters of the hash for comparison as they are unique.

:question: Do they match?

:::info

Some systems have `md5sum` others have a tool called `md5`. Both use exactly the same equation, and so will give the same answer, they just reverse the order it's displayed. If you use a system that has `md5` the order of the answer is:

```

MD5 (ERR458493.fastq.gz) = 2b8c708cce1fd88e7ddecd51e5ae2154

```

for `md5sum` the answer is:

```

2b8c708cce1fd88e7ddecd51e5ae2154 myproject/raw_data/ERR458493.fq.gz

```

:::

:::success

### Exercise :writing_hand:

Check that you have the correct hash (26e91cde337004233b7f43aff7102828) for the *Saccharomyces_cerevisiae* transcriptome

Put up a :hand: on Zoom when you have verified the genome file

:::spoiler Hint!

```bash=1

md5sum myproject/ref_files/Saccharomyces_cerevisiae.R64-1-1.cdna.all.fa.gz

```

:::

---

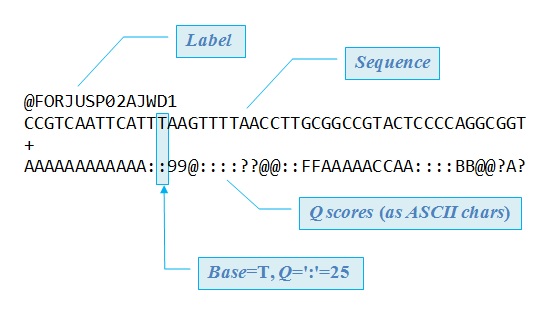

### Anatomy of FASTQ File

Doing your experiment, prepping all those samples and having them sequenced was expensive. It's good to do a couple other quick checks to make sure that the files look ok. The md5 hashsum told us that we got the file intact, but it doesn't tell us if the data inside the file looks right. To do that, we're going to do a quick visual check, and a math check.

For the visual check, let's look at a bit of our sequencing file:

```bash=3

zcat myproject/raw_data/ERR458493.fq.gz | head

```

This file is a FASTQ file that is gzipped (that's what .fq.gz means). So this command first unzips it in place (`zcat`) then sends that output (`|`) to the `head` command, which take just the first 10 lines of a file and displays them on the screen.

What we see is a few repeating chunks of information. FASTQ files are files that store all of the information about each read. Each read gets 4 lines of information.

It's easier to see if we ask `head` to just display the first 4 lines:

```bash=4

clear # this clears your screen

zcat myproject/raw_data/ERR458493.fq.gz | head -n 4

```

- Line 1 always starts with an `@` and is the name of the read. Often, but not always, the name line also has information about where that read was in the sequencing lane. the `DHKW5DQ1:219:D0PT7ACXX:1:1101:1724:2080/1` part of the first line of our file is basically a complex way of telling you the make and model of the sequencer it was run on (notice that the `DHKW5DQ1:219:D0PT7ACXX` is always repeated for our files), then the corrdinates of where this particular read was in the sequencer. The `/1` at the end tells you that the read came from the forward strand.

- Line 2 is the sequence of the read.

- Line 3 always starts with a `+` and often is blank, or just repeats the stuff from line 1, but is a place for extra information

- Line 4 is the quality score for each base. The quality score is *encoded* in some way, and the encoding changes from company to company and across time. For modern Illumina reads, a score of 0 is the lowest quality score, and a score of 40 is the highest. Instead of typing the scores as numbers, they are each encoded as a character.

```

Quality encoding: !"#$%&'()*+,-./0123456789:;<=>?@ABCDEFGHI

| | | | |

Quality score: 0........10........20........30........40

```

A score of 10 indicates a 1 in 10 chance that the base is inaccurate. A score of 20 is a 1 in 100 chance that the base is inaccurate. 30 is 1 in 1,000. And 40 in 1 in 10,000.

Until recently, you needed to know what encoding your data used and feed that into the parameters of your sequencing pipeline, but nearly all modern sequencing tools have started auto-detecting the encoding, so this is only something you need to worry about if you have very old sequence (more than 5 years or so) that might not be included in the tools knowledge base. If you ever need to figure it out, you can use this [chart from wikipedia](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/FASTQ_format) to figure it out by comparing the quality scores in your file to the ones available in any given encoding:

With this information, we can do a visual check! What should we look for?

- First line of the file starts with `@`

- The first and third line for any sequence we check are exactly the same length

- If we got paired end reads, there should be some first lines that end in `/1` and `/2` or a similar notation.

- If we got single end reads, we shouldn't have any `/2`s

- Count the number of letters in your first read (line 2) is it the number of bases you paid for?

Obviously you won't check every read in the file like this, but it's good to check the first few lines (with `head`) and the last few lines (with `tail`) whenever you get your new sequences.

for `tail`, be sure

- your file ends with a quality line

- your sequences haven't changed length

```bash=7

zcat myproject/raw_data/ERR458493.fq.gz | tail

```

Because we now know something about the format of this file, we can also see if the overall size of the file makes sense. To do this, we'll `zcat` our file to a different command line tool wordcount: `wc`. We'll do `wc -l` to have it count how many *lines* are in the file:

```bash=8

zcat myproject/raw_data/ERR458493.fq.gz | wc -l

```

:::success

### Exercise :writing_hand:

What can knowing the number of lines tell you?

Put up a :hand: on Zoom when you have an answer

:::spoiler Hint!

This file has 4375828 lines, which means it must have 4375828/4 = 1093957 sequences in it. If we had gotten a non-round number answer, that would tell us that the file wasn't formatted correctly somewhere or had missing or extra data. We can also check the number of sequences against the number of reads the sequencing facility said they sent to make sure they're similar.

:::

---

## Caretaking

We are pretty sure our sequencing file is ok, so there's one more thing to do before we start doing a lot of work with it: We should make sure we can't accidently delete or change it.

```bash=0

ls -l myproject/raw_data/

```

:::info

### Reproducible Data Practice :eyes:

By default files are writeable – they have `w` in their permissions - which means we can edit or delete them. By default, UNIX makes things writeable by the file owner. This means we can accidently create typos or errors in raw data, which could drastically change our results but be very hard to notice. Raw data should always stay raw! Changing the permissons of raw files keeps them raw.

:::

Let’s fix that before we go on any further:

```bash=1

chmod a-w myproject/raw_data/ERR458493.fq.gz

```

Here we are using the chmod command (for change mode, which handles permissions of files/directories), and providing the argument a-w, which means for all users (a), take away (-) the permission to write (w).

If we take a look at their permissions now:

```bash=2

ls -l myproject/raw_data/

```

We can see that the ‘w’ in the original permission string (-rw-rw-r--) has been removed from the file and now it should look like -r--r--r--.

:::success

### Exercise (Bonus) :writing_hand:

Change the permissions of the md5 file.

Put up a :hand: on Zoom when you're finished

:::spoiler Hint!

```bash=1

chmod a-w myproject/raw_data/err_md5sum.txt

```

:::

---

==Instructor Switch!==

## Quality Assurance

We've convinced ourselves these files are worth working on, we've fixed them so we can't accidently ruin them, so lets start with quality checking!

```bash=1

fastqc myproject/raw_data/ERR458493.fq.gz --outdir myproject/raw_data/fastqc

```

This command runs the tool `fastqc` on our raw sequencing file, and saves the output in our `raw_data/fastqc` directory

:::success

### Exercise :writing_hand:

Can you use `tree` to verify that your command ran successfully?

In the zoom chat, type in the number of files that `fastqc` makes

:::spoiler Hint!

```bash=

tree myproject/

```

Shows that we now have a zip file and an html file in the raw_data fastqc folder

:::

:::success

### Exercise :writing_hand:

Using the Files/Plots/Packages pane to navigate to the files generated by fastqc and click on the `html` file to open it in another tab of your browser.

:::spoiler Hint!

Following the path from the tree image, click on 'myproject', then 'raw_data', then 'fastqc' to see them.

:::

---

### Anatomy of a FastQC report

- **Basic Statistics-** the metadata about this sequencing file

- **Per Base Sequence Quality-** overview of the range of quality values across all bases at each position in the FastQ file

- **Per Tile Sequence Quality-** deviation from the average quality for each tile

- **Per Sequence Quality Scores-** allows you to see if a subset of your sequences have universally low quality values

- **Per Base Sequence Content-** proportion of each base position in a file for which each of the four normal DNA bases has been called

- **Per Sequence GC Content-** GC content across the whole length of each sequence in a file and compares it to a modelled normal distribution of GC content

- **Per Base N Content-** percentage of base calls at each position for which an N was called

- **Sequence Length Distribution-** distribution of fragment sizes in the file which was analysed

- **Sequence Duplication Levels-** degree of duplication for every sequence in a library and creates a plot showing the relative number of sequences with different degrees of duplication

- **Overrepresented Sequences-** lists all of the sequence which make up more than 0.1% of the total sample

- **Adapter Content-** cumulative percentage count of the proportion of your library which has seen each of the adapter sequences at each position

There are some important things to know about FastQC - the main one is that it only calculates certain statistics (like duplicated sequences) for subsets of the data (e.g. duplicate sequences are only analyzed within the first 100,000 sequences in each file). You can read more about each module at [their docs site.](https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/Help/3%20Analysis%20Modules/)

---

## Trimming

Rarely are your sequences good enough that you don't want to trim at all. Here we're doing fairly light trimming just to get rid of any adaptors and very bad bases:

```bash

trimmomatic SE myproject/raw_data/ERR458493.fq.gz myproject/trimmed/ERR458493.qc.fq.gz ILLUMINACLIP:myproject/ref_files/TruSeq2-SE.fa:2:0:15 LEADING:2 TRAILING:2 SLIDINGWINDOW:4:2 MINLEN:25

```

:::info

### Reproducible Data Practice :eyes:

Notice that we are inputing raw_data `myproject/raw_data/ERR458493.fq.gz` and outputting trimmed data `myproject/trimmed/ERR458493.qc.fq.gz`. For that output file we've both directed it to the trimmed folder AND slightly changed the filename to indicate it has had quality control done. Using consistent folders and file naming schemes like this makes it much easier to check your command by eye and to be sure you're using the inputs and outputs you mean to!

:::

Note that trimmomatic is actually a java program that we call from the command line, so it’s syntax is a little confusing. The arguments are followed by a colon, and then what you are specifying to them.

#### Code Breakdown

| Flag | Meaning |

|--------------------|------------------------------------------------------------------|

SE | this is specified because we are working with single-ended data, rather than paired-end data where there are forward and reverse reads|

ERR458493.fastq.gz | the first positional argument we are providing is the input fastq file (note it is okay to provide compressed .gz files to trimmomatic) |

ERR458493.qc.fq.gz | the second positional argument specifies the name of the output files the program will generate |

ILLUMINACLIP:TruSeq2-SE.fa:2:0:15| here we are specifying the argument we’re addressing “ILLUMINACLIP”, first specifying the file holding the adapter sequences, then 3 numbers: “2” which states how many mismatches between the adapter sequence and what’s found are allowed; “0” which is only relevant when there are forward and reverse reads; and “15” which specifies how accurate the match must be |

LEADING:2 TRAILING:2 | both of these are stating the minimum quality score at the start or end of the read, if lower, it will be trimmed off |

SLIDINGWINDOW:4:2 | this looks at 4 basepairs at a time, and if the average quality of that window of 4 drops below 2, the read is trimmed there |

MINLEN:25 | after all the above trimming steps, if the read is shorter than 25 bps, it will be discarded |

---

## Quality Assurance II

Now that we've trimmed, we should look at the FastQC report to see what (if anything) has changed and whether we want to adjust any parameters.

```bash=

fastqc myproject/trimmed/ERR458493.qc.fq.gz --outdir myproject/trimmed/fastqc/

```

:::success

### Exercise :writing_hand:

Compare the trimmed FastQC report to the original one. What has changed? Has it improved the data?

:::spoiler Answer

- There are fewer reads, but not drastically so

- The sequence length has gotten shorter on average and now has a much wider range

- per base sequence quality hasn't really changed

- the first few (~9) bases of reads still look a little dodgy

:::

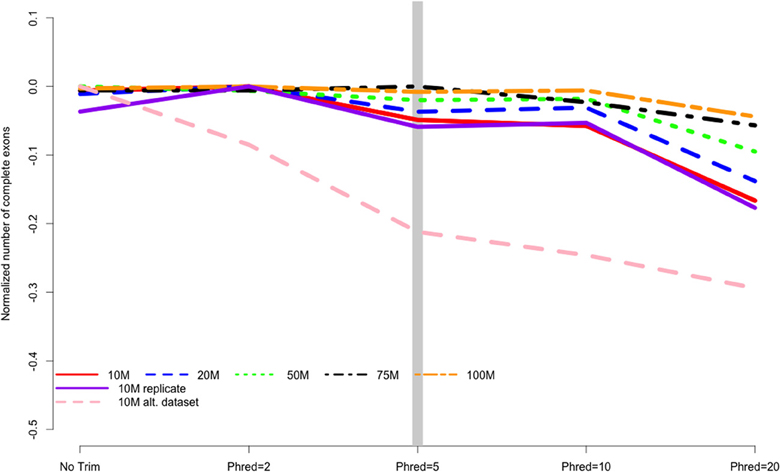

Is this trimming good enough? As with everything else in RNA-Seq, this not easy to answer. For guidance, lets turn to a paper that [emperically tested a number of trimming parameters](https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2014.00013) to see how they changed the results of mapping, which directly influences how much differntial expression you can measure.

This figure shows how many complete exons were recovered from datasets with various trimming levels (the x-axis) and numbers of reads (the lines). What we see is that at a Phred score cutoff of 2 all the datasets except the 10M alt dataset recovered all of the available exons, but at no trim and more stringent trims recovery of exons decreased. The orange line shows that if you have many, many reads (hundreds of millions) then you can get away with more stringent trimming, but if you have low or moderate numbers of reads (the other lines) trimming more gently will likely give you better results.

Image credit https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2014.00013

:::info

### Reproducible Data Practice :eyes:

Whatever trimming parameters you choose, it's important to record them. This is true of all the parameters you set in a given experiment. One easy way to ensure you know exactly what you did is to record your commands as you run them in a text file and save that file in your project folder. Then if you run a few different analyses on the same data, you not only know which data output files go together, but exactly how you made them.

:::

:::success

### Exercise :writing_hand:

We can test to see if increasing the trimming makes a large difference in this dataset.

Re-run trimmomatic with leading and trailing minimum scores of 5, then run a FastQC report for your new trim. Be sure to name the output files something that will distinguish them from the ones you already have.

Compare the fastqc report to the one with a minimum of 2. Has it improved the data?

:::spoiler Hint!

```bash

trimmomatic SE myproject/raw_data/ERR458493.fq.gz myproject/trimmed/ERR458493.qc5.fq.gz ILLUMINACLIP:myproject/ref_files/TruSeq2-SE.fa:2:0:15 LEADING:5 TRAILING:5 SLIDINGWINDOW:4:2 MINLEN:25

fastqc myproject/trimmed/ERR458493.qc5.fq.gz --outdir myproject/trimmed/fastqc/

```

:::

---

## Running Salmon

"Salmon provides accurate, fast, and bias-aware transcript expression estimates using dual-phase inference" [Patro et al., 2016](http://biorxiv.org/content/early/2016/08/30/021592).

[Salmon](https://salmon.readthedocs.io/en/latest/salmon.html) is a tool for fast transcript quantification from RNA-seq data. It requires a set of target transcripts (either from a reference or de-novo assembly) to quantify and FASTA/FASTQ file(s) containing your reads.

### Generating a Salmon index

Salmon runs in two phases, indexing and quantification. The indexing step is independent of the reads, and only needs to be run one for a particular set of reference transcripts.

If you start with the basic Salmon documentation, you'd likely start by creating an indexing command like this one.

```bash

salmon index --index myproject/quant/sc_ensembl_index --transcripts myproject/ref_files/Saccharomyces_cerevisiae.R64-1-1.cdna.all.fa.gz

```

:::success

### Exercise :writing_hand:

What kinds of files does indexing make and what do they tell you?

Either in the command line or the file browser check out one or two of the files that were created. Avoid the `.bin` files, these are in binary and won't open. What is in the non-binary files? Are any of them useful? Report back in the chat if you find something that seems important.

:::spoiler Hint!

- the duplicate_clusters.tsv file shows which mRNA sequences were filtered out as duplicates

- the `.json` files have information about the version of the tool you used and what parameters it ran with

- `.log` files have some information about what happened in this specific instance of running the command

- check the resulting `pre_indexing.log` file in particular

:::

---

A warning isn't the same as an error, and we could proceed without making decoy sequences, [but it would likely make our analysis a little worse.](https://salmon.readthedocs.io/en/latest/salmon.html#preparing-transcriptome-indices-mapping-based-mode)

One of the novel and innovative features of Salmon is its ability to accurately quantify transcripts without having previously aligned the reads using its fast, built-in selective-alignment mapping algorithm. Further details about the selective alignment algorithm can be found [here](https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/657874v1).

It is generally recommended that you build a decoy-aware transcriptome file. From salmon paper:

> Our approach also determines when even the best mapping for a read exhibits insufficient evidence that the read truly originated from the locus in question, allowing it to avoid spurious mappings.

> We also attempt to address one of the failure modes of direct alignment against the transcriptome, instead of the genome.

> When a sequenced fragment originates from an unannotated genomic locus bearing sequence similarity to an annotated transcript, it can be falsely mapped to the annotated transcript since the relevant genomic sequence is not available to the method

> The normal Salmon index is then augmented with these decoy sequences, which are handled in a special manner during mapping and alignment scoring, leading to a reduction in false mappings of such a nature.

There are a couple of ways that you can generate decoy sequences. One easy way is to add the genome to the end of the transcriptome [using this tutorial](

https://combine-lab.github.io/alevin-tutorial/2019/selective-alignment/). This will make our index much bigger however, and will likely make the pipeline a lot slower for species with larger genomes. If you have species with a larger genome, [Salmontools](https://github.com/COMBINE-lab/SalmonTools/blob/master/README.md) has a tutorial for making a smaller decoy file. Or pre-built versions of both the partial decoy and full decoy (i.e. using the whole genome) salmon indices for some common organisms are available via refgenie [here](http://refgenomes.databio.org/).

### How to build a better index

There are three basic steps to using decoys in your index:

- Add some sequences that aren't your transciptome to your transciptome file and call that something like`combined.fa`

- Make a list of the names of those fake sequences and call it something like`decoys.txt`

- When you run the index command, use the `combined.fa` file as your transcriptome and tell the indexing command what the decoys file is using the `-d` flag

For this lesson I've pre-built a decoy file and saved them in the `yeast_ref` folder, but if you wanted to make your own, you would use these commands:

:::info

1. First you would need to download the *Saccharomyces cerevisiae* genome:

```bash

curl -L https://www.ebi.ac.uk/ena/browser/api/fasta/BK006935.1,BK006936.1,BK006937.1,BK006938.1,BK006942.1,BK006939.1,BK006940.1,BK006941.1,BK006934.1,BK006943.1,BK006944.1,BK006945.1,BK006946.1,BK006947.2,BK006948.1,BK006949.1?download=true -o myproject/ref_files/ena_data_20210618-1753.fasta

```

2. Then you would need to concatanate that genome sequences onto the end of our trancriptome file and make them into a new file called `Saccharomyces_cerevisiae_combined.fa`

```bash

cat <(gunzip -c myproject/ref_files/Saccharomyces_cerevisiae.R64-1-1.cdna.all.fa.gz) myproject/ref_files/ena_data_20210618-1753.fasta > yeast_ref/Saccharomyces_cerevisiae_combined.fa

```

3. Then you would pull out all the chromosome names from the genome file and put them in a list called `decoys.txt`.

```bash

# This line searches for all the lines that start with `>` and saves the first word in that line (the name of the chromosome)

grep "^>" myproject/ref_files/ena_data_20210618-1753.fasta | cut -d " " -f 1 > yeast_ref/decoys.

# This next line formats the file by removing the `>` character so it's just the name

sed -i.bak -e 's/>//g' yeast_ref/decoys.txt

```

:::

Run the indexing with the decoys file by using the file we index to be `Saccharomyces_cerevisiae_combined.fa` file, and telling it where to find the decoys with `-d`:

```bash

salmon index --index myproject/quant/sc_ensembl_index --transcripts yeast_ref/Saccharomyces_cerevisiae_combined.fa -d yeast_ref/decoys.txt

```

:::success

### Exercise :writing_hand:

Check for warnings. Look at the pre_indexing.log file and see what it says.

:::

---

### Quantify reads with Salmon

The quantification step is specific to the set of RNA-seq reads (the sequencing file) and so is run once for every sequencing file.

```bash

salmon quant -i myproject/quant/sc_ensembl_index --libType A -r myproject/trimmed/ERR458493.qc.fq.gz -o myproject/quant/ERR458493_quant --seqBias --gcBias --validateMappings

```

#### What do all of these flags do?

| Flag | Meaning |

|--------------------|------------------------------------------------------------------|

| -i | path to index folder |

| --libType | The library type of the reads you are quantifying. `A` allows salmon to automatically detect the library type of the reads you are quantifying. |

| -r | Input file (for single-end reads) |

| -o | output folder |

| --seqBias | learn and correct for [sequence-specific biases](https://salmon.readthedocs.io/en/latest/salmon.html#seqbias) in the input data |

| --gcBias | learn and correct for [fragment-level GC biases](https://salmon.readthedocs.io/en/latest/salmon.html#seqbias) in the input data |

| --validateMappings | Enables [selective alignment](https://salmon.readthedocs.io/en/latest/salmon.html#validatemappings), which improves salmon's sensitivity |

As Salmon is running, a lot of information is printed to the screen. For example, we can see the mapping rate as the sample finishes:

```

[2021-06-18 01:52:42.223] [jointLog] [info] Mapping rate = 84.4955%

```

:question: **What files did this generate?**

Let's take a look at some Salmon output.

```

ls myproject/quant/ERR458493_quant/

```

You should see output like this:

The information we saw scroll through our screens is captured in a log file in

`aux_info/`. Use the file navigator to find and open that file.

We see information about our run parameters and performance.

:::info

If you were working entirely in the command line, you'd probably look at this file with`less`

```

less myproject/quant/ERR458493_quant/aux_info/meta_info.json

```

`less` is a tool that reads a file onto your screen so you can look at it without opening it in a text editor. You navigate up and down with the arrow keys. To exit out of the

file, press `q`.

:::

:::success

### Exercise :writing_hand:

The file we're most interested in is the count file. It's called `quant.sf`. Navigate to it and open it. What is in this file?

:::spoiler Hint!

Click 'myproject' then 'quant' then the name of the sample you want 'Err458493_quant' then 'quant.sf'

or do

```

less myproject/quant/ERR458493_quant/quant.sf

```

:::

We see our transcript names, as well as the number of reads that aligned to each transcript.

:::success

### Exercise :writing_hand:

What would you expect to happen if you ran Salmon on 2 sequencing files?

:::spoiler Answer

```bash=

tree myproject/

```

Salmon outputs one folder for each input RNA-seq sample, so there would be 2 folders and twice as many files!

:::

:::success

### Exercise :writing_hand:

Try it!

Run Salmon on the more stringently trimmed version of your file.

How did it go? In the zoom chat tell us whether more stringent trimming improved your mapping rate.

:::spoiler Hint!

You don't need to re-run the index, so:

```bash=

salmon quant -i myproject/quant/sc_ensembl_index --libType A -r myproject/trimmed/ERR458493.qc5.fq.gz -o myproject/quant/ERR458493_quant5 --seqBias --gcBias --validateMappings

```

Be sure you change the input AND output file names so you don't overwrite the files you just made.

:::

---

## Running with multiple files

We've been using just one sequencing file representing sequences from one individual, but in a real RNA-Seq experiment you normally have many sequencing files, one for each individual. As we've seen, the number of files gets very large very quickly, and it's really important to be organized and deliberate about our work. So, when you do a larger analysis, you won't want to run one sample at a time. It's very error prone and very, very boring. Instead, you would run some kind of automated pipeline- code that has been written in such a way that it can do many files at once. The simplest possible way to do that would be a loop, but loops are pretty slow. For these files, we've written a Snakemake pipeline. It takes each of the steps we've done and automatically does them for every sample. Obviously it can't do things like look at FastQC reports for us, but it does make it a lot easier.

To start your Snakemake pipeline and automagically process 6 samples all at once do:

```bash=

snakemake -j 4 --use-conda

```

We don't have time to teach you Snakemake today, but if you'd like to learn how to make your own Snakemake pipelines, look for our next Snakemake workshop!

:::success

### Exercise :writing_hand:

Snakemake is working in a different folder than you were so it won't overwrite all your hard work. Using one of the methods you've learned today, checkout the 'rnaseq' folder to see what the output for 6 files look like. Try to answer some of these questions:

- How does quality compare across the six samples?

- How do mapping rates compare across samples?

- The automated pipeline is coded to use a slightly different folder setup. Do you like one better than the other? How would you organize your workspace to make the most sense to you?

:::spoiler Hint!

Click 'rnaseq' then explore from there

or do

```

tree rnaseq

```

to get an overview

In this set up:

- fastqc folder is a multiqc that lets you look at all 6 files together and is slightly nicer than fastqc. It is the untrimmed reads

- quality folder is all the trimmed reads as well as the fastqc for the trimmed reads

- quant is the same, just for 6 files

- raw_data is the raw_reads as well as the fastqc for the raw reads

:::

## End of Day 1

We've learned how to build a directory structure, run quality control on both raw and trimmed files, and quasi-mapped reads to a transcriptome to get counts per transcript.

In the next session, we'll be working in R to summarize the counts to the gene level, explore our data, run a differential expression analysis and look at the results.

---

:::warning

## One up, One down. :pencil:

Please tell us how today went! We use the feedback to help improve our training materials and future workshops. Link here: https://easyretro.io/publicboard/u1d2YYNNKVNuCOd3MWM7gji0cCX2/4cf0db1e-3ca0-45d7-9895-dcd1dc1e0e65

:::

## :question:Questions?

To start Day 2, open the file called `rnaseq-workflow.html` in your binder instance

---

## Resources

- [CFDE training webite](https://training.nih-cfde.org/en/latest/)

- [References and further reading](https://hackmd.io/vxZ-4b-SSE69d2kxG7D93w)

- [Workshop additional resources/FAQ](https://hackmd.io/RweX2WZ7RGGtfLfCDuEubQ)

- [CFDE events & workshops](https://www.nih-cfde.org/events/)

- [DIB Lab video about RNA-Seq Concepts](https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4cndEDLIGVU&feature=youtu.be)

## Bonus Content: How to do this on your own machine

Please [sign up for our workshops](https://www.nih-cfde.org/events/) on getting set up in AWS and using Conda as those two workshops will give you a much better understanding, but breifly:

Everything we did in the cloud today was in a Conda environment. To replicate it on an AWS or GCP computer, or your own laptop you would:

- [Install conda](https://conda.io/projects/conda/en/latest/user-guide/install/index.html)

- Get the file called `rnaseq-env.yml` from this binder. You can open a new binder and download it from there, or [download it from our github repo for this lesson](https://github.com/nih-cfde/rnaseq-in-the-cloud/blob/stable/rnaseq-env.yml)

- In the terminal on your AWS/GCP/laptop, type in the same commands we used today to create a conda environment from that file:

```

conda init

echo "PS1='\w $ '" >> .bashrc

source .bashrc

conda env create -f rnaseq-env.yml

conda activate rnaseq-qc-map

```

- And that's it! If it all installed correctly, you now have an environment with exactly the same tools you had today.

Sign in with Wallet

Sign in with Wallet