# Tools of Scientific Computing

[](https://hackmd.io/Yn-f103pQkC-_wwQwwx5-Q)

###### tags: `Kickstart`

###### *Work in progress by `simo.tuomisto@aalto.fi`. Looking for contributors/co-authors, add your name if you contributed. All original text and images under [CC-BY 4.0](https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/). *

##  Journey of scientific computing is a winding one

As showed in the [short introduction to scientific computing](https://hackmd.io/@AaltoSciComp/SciCompIntro), a typical research project might look like this:

*Figure 1 - A common pipeline of scientific computing*

A single project can require a huge number of skills and tools:

- data cleaning

- programming

- running computational simulations

- testing and profiling

- documenting

- data plotting

- sharing data/code with collaborators

Any skills learned through a project are often **reused in subsequent projects** as well.

This brings an interesting problem:

> I suppose it is tempting, if the only tool you have is a hammer, to treat everything as if it were a nail.

> - [Abraham Maslow](https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/if_all_you_have_is_a_hammer,_everything_looks_like_a_nail)

This means that even **bad habits can be reused** in subsequent projects.

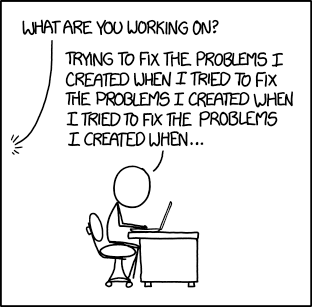

*Figure 2 - [xkcd #1739: Fixing Problems](https://xkcd.com/1739/)*

Thus one should always keep a critical eye on what you're using and whether it is a good tool for the job at hand.

In the next sections we look through some tools and skills that might help you on your journey.

However, remember that these are just suggestions and if your tools work for you, maybe you're using the correct tools for the correct task.

##  Packing your bag for a small journey of exploration

Small journey is a situation where you want to get a quick glimpse of a possible project.

Maybe you want to explore a new dataset, to test out a new algorithm or to see if you can use a new programming language.

For these kinds of projects you should invest in the following:

1. Pick a scientific programming language of your choice.

2. Pick an editor or an IDE with syntax highlighting.

3. Use an interactive IDE that allows you to write your code as a script while you're running it.

### Scientific programming languages

There are many programming languages that can be used for general scientific computing. These kinds of languages can do (among other things):

* Easy file input/output.

* Mathematical functions e.g. linear algebra.

* Easy plotting features.

* Good tools for calling other languages.

* Robust packaging ecosystem.

*Figure 3 - Arbitrary definition of a generic scientific programming language*

#### Python

[Python](https://www.python.org/) is the most popular language for general scientific computing. The main features are:

* Very popular for various uses.

* Scientific package ecosystem provided by the [numpy](https://numpy.org/) family of packages (numpy, scipy, matplotlib, pandas, scikit-learn etc.).

* Generic programming language, so it has good packages for web applications etc.

#### Matlab

[Matlab](https://se.mathworks.com/products/matlab.html) is a commercial numerical computing language. It is quite popular in signal processing and in laboratories. The main features are:

* Comprehensive IDE.

* [Toolboxes](https://se.mathworks.com/help/thingspeak/matlab-toolbox-access.html) provided by Matlab.

When working with Matlab it is good to remember that it is a commercial product and not everyone can access a licence of it.

#### Julia

[Julia](https://julialang.org/) is a newer language that has been designed for high-performance computing. The main features are:

* Fast.

* Designed for scientific computing from the beginning.

* Good [package ecosystem](https://julialang.org/packages/) for scientific computing.

#### R

[R](https://www.r-project.org/) is a language for statistics and data analysis. It is especially popular in statistics and bioinformatics. The main features are:

* Designed for statistics and data science.

* Huge number of [packages](https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/index.html).

### Editors and IDEs

There are plenty of good editors and IDEs. Here's a list of some of the most popular ones.

#### Graphical editors

Generic IDEs:

- [VSCode](https://code.visualstudio.com/)

- [Atom](https://atom.io/)

- [Sublime Text](https://www.sublimetext.com/)

Python IDEs:

- [PyCharm](https://www.jetbrains.com/pycharm/)

- [Spyder](https://www.spyder-ide.org/)

- [JupyterLab](https://jupyter.org/)

Julia IDEs:

- [Julia for VSCode](https://www.julia-vscode.org/)

R IDEs:

- [Rstudio](https://www.rstudio.com/)

#### Text-based editors:

- [emacs](https://www.gnu.org/software/emacs/)

- [vim](https://www.vim.org/) or [neovim](https://neovim.io/)

- [nano](https://www.nano-editor.org/)

### Using scripts or notebooks instead of an interactive console

Even when you're testing stuff it is a good idea to write your code as a script or as a Jupyter notebook. This way your ideas will not disappear when you close your console.

Working like this might seem self-evident, but it is important to keep in mind what commands you have written. Saving your code is the first step of documenting your work.

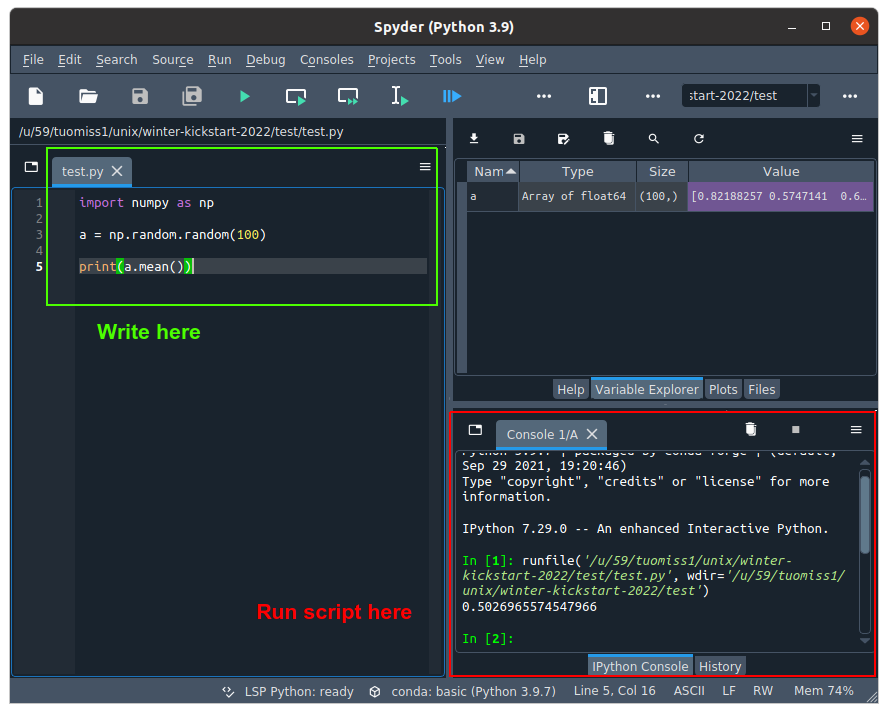

#### Writing scripts in IDEs

IDEs commonly have an interactive console and an editor window where you can write your scripts. You can run commands in the console itself, but it is better practice to write your code as a script and then execute the code in the interactive console.

*Figure 4 - Writing a script with an IDE*

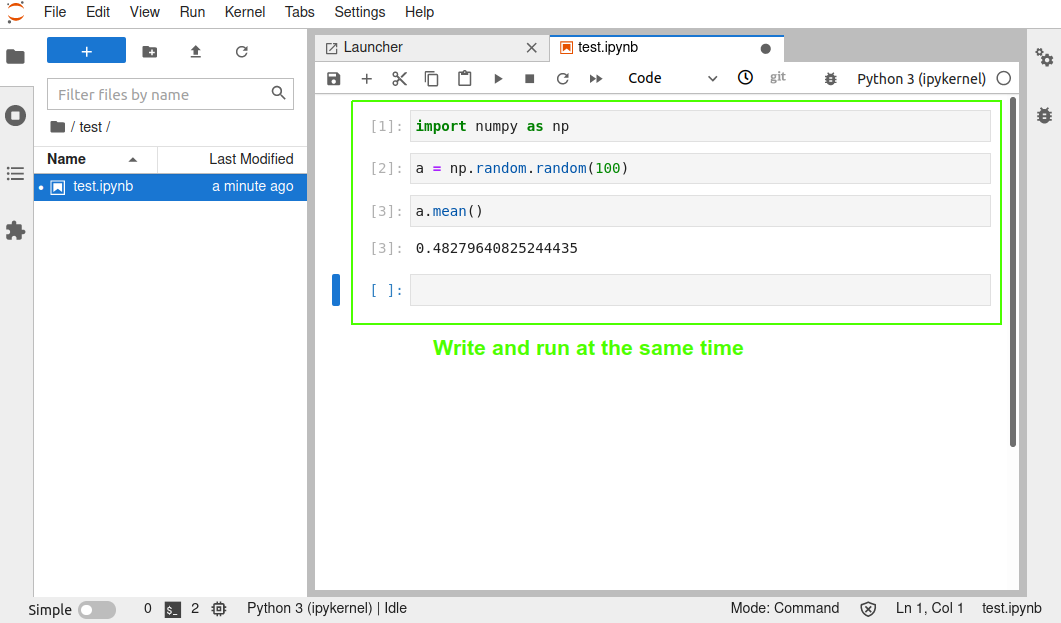

#### Writing a notebook with Jupyter

[Jupyter](https://jupyter.org/) notebooks work a bit differently to typical scripts. A notebook is split into cells that can contain code or documentation. Code cells can be executed by a kernel, which [can be of any language](https://github.com/jupyter/jupyter/wiki/Jupyter-kernels).

*Figure 5 - Writing a notebook*

For more on Jupyter, see for example:

- [CodeRefinery's course on Jupyter](https://coderefinery.github.io/jupyter/)

- [Jupyter in Triton](https://scicomp.aalto.fi/triton/apps/jupyter/)

##  What you should pack for a new project

A new project is something that takes more than a few days to complete.

Even a single weekend or working on a different project can break your train of thought and thus it is important to record your work.

Maybe your initial exploration looked promising and now you want to try it out **for real**.

For these kinds of projects you should invest in the following:

1. Use a version control system with a remote provider.

2. Do some simple documentation and commenting.

3. Keep track of any requirements.

4. When possible, use already existing scientific computing packages and frameworks.

### Using version control

Version control is an invaluable tool whether you're doing scientific research or software engineering and [Git](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Git) is by far the most popular version control tool available.

Version control tools such as git will track changes on a line by line basis and will record changes into commits. This allows users of version control to revert changes, merge commits made by other collaborators and keep code up to date across multiple systems.

Thus if you do not use version control, start learning on git immediately. There are plenty of good resources such as:

- CodeRefinery's [intro to version control.](https://coderefinery.github.io/git-intro/)

- Software Carpentry's [git course](https://swcarpentry.github.io/git-novice/).

There are many providers for centralized repository storage. For public projects:

- [GitHub](https://github.com/) is an excellent choice for any projects that do not have proprietary secrets or private data. Nowadays free users can create private repositories as well.

- [version.aalto.fi](https://version.aalto.fi/gitlab/) is a private GitLab instance for Aalto students and employees.

Whenever you're starting a new project, it is a good idea to start by creating a new repository for the project.

### Commenting & documenting

Commenting your code and your project will help you and your collaborators in keeping track of the different pieces of the project.

You might think that you can keep all of the moving pieces in your memory, but that will put unnecessary pressure on your long-term memory. It's better to remember the big picture and whenever you need to look at the details, you look at the comments to refresh your memory.

There are plenty of tools that help with commenting:

- Markdown (or [CommonMark](https://spec.commonmark.org/0.30/) as the standard is called) is a lightweight and easy markup language. There are plenty of good Markdown cheat sheets such as [this](https://www.markdownguide.org/cheat-sheet/) and [this](https://github.com/adam-p/markdown-here/wiki/Markdown-Cheatsheet). This HackMD document is written in Markdown as well!

- There are various [style guides](https://mitcommlab.mit.edu/broad/commkit/coding-and-comment-style/) for different programming languages. Taking one standard and following the convention will help you write good looking code and you don't have to worry about choosing comment styles etc.

- You can use linters: programs that check whether your code has syntax errors and style errors to. For list of linters, see for example [this page](https://github.com/caramelomartins/awesome-linters)

It is good to also remember that no-one likes commenting and documenting.

### Keeping track of requirements

All projects will utilize programs that are not part of the project. Keeping track of these requirements from the start is very important, as it allows you to:

- Know what your program needs.

- Recreate your environment easily.

- Help your collaborators replicate your environment.

- Debug problems with the installed versions of software.

There are various ways of keeping track of you requirements. Below are few examples:

- Keep a text file with a list of commands you have run when you installed the program

- Keep a simple documentation (such as a markdown `INSTALL.md`) with instructions on how to install the program

- Keep a requirements file such as `requirements.txt` (PIP), `environment.yml` (conda) that works with a package managing system or keep a list of packages you have installed.

Most important thing is to keep yourself up to date on what your code utilizes and recording it somewhere.

### Using existing packages and frameworks

> If I have seen further it is by standing on the sholders [sic] of Giants.

> - [Isaac Newton](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Standing_on_the_shoulders_of_giants#Isaac_Newton)

No single person can know everything and no one has time to implement every feature themselves. Thus using existing packages and frameworks is imperative for effictive scientific computations.

If you start writing your own function for e.g. calculating an integral or doing a least-squares fit, ask yourself if **someone else has ever needed the same function**. If the answer to that question is yes, most likely someone has already implemented the functionality in a scientific computing package or framework.

By using packages made by others you avoid bugs in your own implementations and you make your code easier to read for other people.

Below are examples of few frameworks that might interest you:

#### Python

- [numpy ecosystem](https://numpy.org/) ecosystem - Numpy ecosystem containts pakcages for scientific calculations, data science, machine learning, plotting etc. (numpy, scipy, pandas, scikit-learn, matplotlib, ...).

- [bioconda](https://bioconda.github.io/) - Collection of packages for bioinformatics.

- [geopython](https://geopython.github.io/) - Collection of packages for working with geospatial data.

- [astropy](https://www.astropy.org/) - Collection of packages for astronomy.

- [PyTorch](https://pytorch.org/) - PyTorch is a popular deep learning framework.

- [Tensorflow](https://www.tensorflow.org/) & [keras](https://keras.io/) - Tensorflow is a popular deep learning framework and Keras is a simpler API for it.

#### Matlab

- [Matlab toolboxes](https://se.mathworks.com/help/thingspeak/matlab-toolbox-access.html) - Official toolboxes from MathWorks for various specialized cases.

- [MathWorks File Exchange](https://se.mathworks.com/matlabcentral/fileexchange/) - Community hub for Matlab packages.

#### Julia

- [Gadfly.jl](http://gadflyjl.org/stable/) - A versatile plotting library.

- [Flux.jl](https://fluxml.ai/Flux.jl/stable/) - A machine learning library for Julia.

- [DifferentialEquations.jl](https://diffeq.sciml.ai/dev/index.html) - A library for solving differential equations.

#### R

- [Tidyverse](https://www.tidyverse.org/) - Environment of helper functions for easier data analysis.

- [gglot2](https://ggplot2.tidyverse.org/) - Extremely popular plotting library.

- [Bioconductor](https://www.bioconductor.org/) - Popular framework for bioinformatics.

- For a good list of other packages, see for example [this community managed list](https://github.com/qinwf/awesome-R/).

###  How to build a foundation for a lasting project

When you're starting on a long-term project, you need to plan ahead for possible future needs.

Maybe you'll want to scale up your computations in an HPC environment. Maybe you'll want to share your project to the wider world.

Like building a house, you'll want to have the project on a solid foundation.

Keeping the following ideas at the back of your head will help you in creating such a foundation:

1. Make sure that it is possible to run your code from the command line.

2. Find the part of your program that does most of the work and optimize that.

3. Think what happens to the project after it is finished.

4. Remember to ask for help when you feel like you need it.

#### Running code from the command line

The [command line](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Command-line_interface) (also known as a [shell](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shell_(computing))) can be used to run programs without a graphical interface. This might seem like an old way of running programs, but in many cases it is the most efficient way.

One of the main advantages of the command line is that it can be used in all kinds of different systems as long as they have the same. Especially in ones that do not have a graphical interface.

Other advantage is that when you're running a program through a command line, you do not need the IDE that was used to create the program. This makes it easier to port the program to other systems and to other users.

These features are imperative in high-performance computing (HPC) systems that usually do not have graphical interface and where you want to focus on running the code and nothing else.

Most popular Unix-style shells are:

- [bash](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bash_(Unix_shell)) - Easier and older style of shell. Default shell in most Linux distributions.

- [zsh](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Z_shell) - More robust, but also more complex shell. Default shell in macOS.

To learn more on command line usage, see:

- [Aalto Scicomp course on linux shell](https://aaltoscicomp.github.io/linux-shell/)

- [SoftwareCarpentry's course on Unix shell](https://swcarpentry.github.io/shell-novice/)

Most languages also have libaries or tools for creating easy command line interfaces. Here are few examples:

- [argparse](https://docs.python.org/3/library/argparse.html), [click](https://click.palletsprojects.com/en/8.0.x/), [docopt](http://docopt.org/) and [fire](https://github.com/google/python-fire) for Python

- [batch-mode startup](https://se.mathworks.com/help/matlab/matlab_env/commonly-used-startup-options.html) and [inputParser](https://se.mathworks.com/help/matlab/ref/inputparser.html) for Matlab

- [ArgParse.jl](https://argparsejl.readthedocs.io/en/latest/argparse.html) for Julia

- [argparse](https://github.com/trevorld/r-argparse), [argparser](https://www.rdocumentation.org/packages/argparser/versions/0.7.1) and [cli](https://cli.r-lib.org/index.html) for R

#### Optimizing at the right places

Typically projects will have parts that are used rarely and some things that are used all the time.

Most scientific programs have similar structure: some parts of the code are called again and again, while some parts are called once or twice.

Thus when you reach a point where you **want to do more**, it is usually important to know what actually takes the time and focus on that.

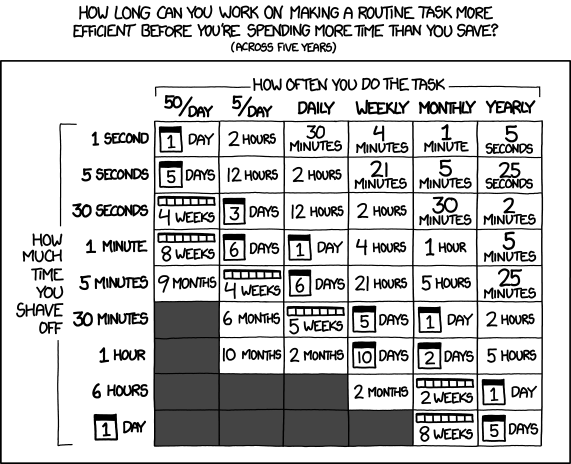

*Figure 6: [xkcd #1205: Is It Worth the Time?](https://xkcd.com/1205/)*

All languages have tools for profiling. They will help you figure out where the bottlenecks might be. Some basic profilers are listed below.

- [Python profilers](https://docs.python.org/3/library/profile.html)

- [Matlab profilers](https://se.mathworks.com/help/matlab/ref/profile.html)

- [Julia profilers](https://docs.julialang.org/en/v1/manual/profile/)

- [Rprof](https://www.rdocumentation.org/packages/utils/versions/3.6.2/topics/Rprof) and [profvis](https://rstudio.github.io/profvis/) for R

After you have profiled which parts of your program take the most time, you can fix possible bugs in the code itself or use specialized libraries to optimize the code.

However, one should try to avoid premature optimization. If the code does not do what you want it to do, running it fast won't help.

#### Think of what happens to the project in the long run

What will happen to the project if I'm not going to update it any more? Will anyone else use this after me? Should I make my project public?

It is good to ask such questions when you start a new project. Knowing what is the end goal of the project will be helps you make choices throughout the project.

In many cases, opening up code in a shared repository and creating code publicly is the best option. This will help you design code not only for yourself, but for others as well.

If fully public design is not an option, using a private repository with your colleagues might be a better one. Getting feedback from your colleagues and minimizing the burden of contributing is always a good idea.

This topic is very wide and there is no good single answer, but for more information, you can check out the following:

- [CodeRefinery's lesson on collaborative git usage](https://coderefinery.github.io/git-collaborative/)

- [CodeRefinery's course on social coding](https://coderefinery.github.io/social-coding/)

- [CodeRefinery's course on reproducible research](https://coderefinery.github.io/reproducible-research/)

#### Remember to ask for help

A single person cannot know everything about everything. Thus whether you're starting a project, designing a project, working on the project or sharing the project with others, you'll encounter questions you do not know the answer for.

Scientific computing is a field where **sharing information** is crucial:

- We write code with editors created by others

- We use programming languages created by others

- We use specialized libraries created by others

- We use scientific models and algorithgms created by others

- We use HPC systems we share with others

- We do research with others

- We share our results with others

At every step of the way, we work with other people, in one way or another. When you encounter a problem, someone else might already have a solution. When you find a solution, someone else might need it to solve their problem.

Sharing information and asking for help are probably the most important skills you might learn when doing scientific computing.

There are many sources of help/information available:

For help:

- Your colleagues

- Scientific computing team in your university ([Aalto Scicomp](https://scicomp.aalto.fi/help/))

- Research software engineers in your university ([Aalto RSE](https://scicomp.aalto.fi/rse/))

For information:

- Documentation of the libraries you're using

- GitHub issues for a package/library you're using

- [Stack Overflow](https://stackoverflow.com/)

- [CodeRefinery](https://coderefinery.org/)

## Image sources

###### [Treasure map icon](https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Noun_Project_Treasure_Map_1460610_cc.svg)([CC-BY-SA-3.0](https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/))

###### [Research project](https://hackmd.io/@AaltoSciComp/SciCompIntro)([CC-BY-SA-4.0](https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/))

###### [xkcd #1739: Fixing Problems](https://xkcd.com/1739/)([CC BY-NC 2.5](https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.5/))

###### [Backpack icon](https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Backpack_icon.svg)([CC-BY-SA-4.0](https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/))

###### [Tent icon](https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Noun_camp_2695642.svg)([CC-BY-SA-4.0](https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/))

###### [House with garden icon](https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:586-house-with-garden.svg)([CC-BY-SA-4.0](https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/))

###### [xkcd #1205: Is It Worth the Time?](https://xkcd.com/1205/)([CC BY-NC 2.5](https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.5/))