## MPI Continued

### 4.1 Welcome to Week 4

In this week we will introduce some advanced MPI topics that you may find useful when asking yourself how to do things better.

A better approach to parallelisation is to overlap computing and communication with non-blocking communication. Another question is if we can reduce memory with MPI and OpenMP gaining in speed with hybrid or one-sided approach? When things get large we would like to combine them together with our own derived types that can simplify programming. At the end of the week we will take a look into parallel writing of files that can be used instead of collecting results over MPI. There are also some advanced MPI topics which we will not cover here in detail and are part of other PRACE courses.

### 4.2 Non-Blocking communications

We saw in the previous week that the types of communication in MPI can be divided by two arguments, i.e., based on the number of processes involved:

- Point-to-Point Communication

- Collective Communication

And another way of dividing would be relating to the completion of an operation, i.e.:

- Blocking Operations

- Non-Blocking Operations

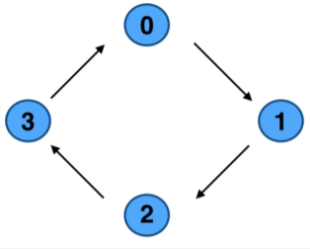

We have seen some problems in the previous modes of communication we have learnt until now. For instance, in the Ring example, where we have a cyclic distribution of processes that we would like to send messages along the ring, we realised that blocking routines are somehow not suitable for this. The problem is that for the second or third process in order to actually receive something, it would have to wait for the message to be sent to the first one and so on. So, evidently we are losing time and not producing a good parallel application.

**Image courtesy: Rolf Rabenseifner (HLRS)**

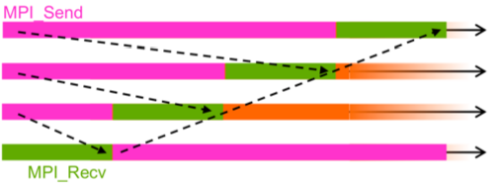

While using blocking routines, when we profile the code it happens quite often that we either have some problem with the deadlocks, that we discussed previously, i.e., either there is some *sent* data that we just never received or vice versa. Even though this situation can be solved, however, there is another more complex problem that can arise. Suppose in the previous example, if we would do it using blocking communication. In that case we would basically *serialize* our code (see image below) and as we can see some of the processes would need to wait; our resources are wasted. This clarifies the need for some other clever way to send messages via this ring without so much waiting time and this is where the non-blocking communication comes into play.

**Image courtesy: Rolf Rabenseifner (HLRS)**

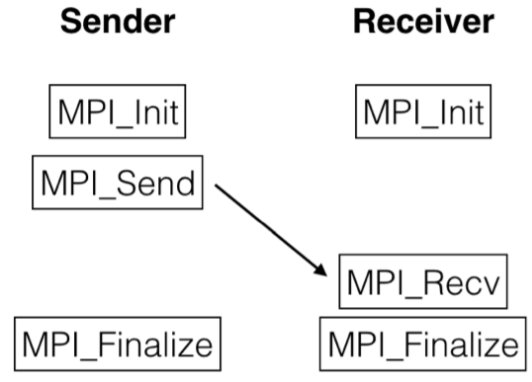

As we already saw in the previous week, that non-blocking routine returns immediately and allows the sub-program to perform other work so we can do some work between and this is useful because, for instance, we can send a message, do some operations, and then we can receive the message. So, these three parts are essential in the non-blocking communications.

So, non-blocking communication is divided into three phases:

- First phase is obviously to initiate non-blocking communication. We will distinguish all imperative which are non-blocking with the capital `I`, which means immediately. So, immediately after MPI and underscore there will be the capital `I`: `MPI_Isend` and `MPI_Irecv`. The protocols will look like:

~~~c

MPI_Isend (void *buf, int count, MPI_Datatype datatype, int dest, int tag, MPI_Comm comm, MPI_Request *request);

~~~

and

~~~c

MPI_Irecv (void *buf, int count, MPI_Datatype datatype, int source, int tag, MPI_Comm comm, MPI_Request *request);

~~~

- Then we can do some other work because when we use this routine, it does not block us, so we can do some operations after this. However, later on we actually have to check whether the message has been received.

- To do this final phase we need to wait for non-blocking communication to complete and we do this by calling the `MPI_Wait` function. This completes the whole process. This request is just another struct in MPI similar to *status*, so we just define it as similar to status and then put on the pointer there. The prototype of this function looks like:

~~~c

MPI_Wait (MPI_Request *request, MPI_Status *status);

~~~

We will understand this more clearly with the help of the following two examples.

### Non-blocking send and receive

**Image courtesy: Rolf Rabenseifner (HLRS)**

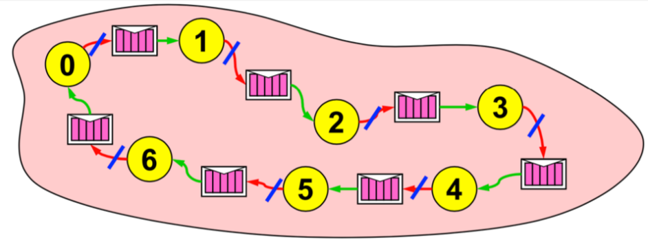

In this example let us assume that all the processes would like to share some information along the ring. As the picture shows, process `0` would like to send something to `1`, `6` would like something to `0` and so on. The idea here is that first we initialize the non-blocking send and we send the message. So, primarily we initiate non-blocking send to the right neighbour. As we know in non-blocking communication after we have done that, we can do some work. In our case we will receive the message via the classical receive function. So, in this ring example, receive the message from the left neighbour. And finally at the end, we have to call the `MPI_Wait` function in order to check if everything was done and for the non-blocking send to complete.

Perhaps you can already see it clearly that fundamentally it is non-blocking in this ring example that helps us, so that every process can start the sending, but at the same time, we can still do something else.

In similar ways we can initiate the non-blocking receive. So in our ring example it would mean that we initiate non-blocking receive from the left neighbour. This would imply that we will receive something, but maybe not now, maybe later, and we do some work. In this case it would mean sending information to the following receiver so, send the message to the right neighbour. Finally, we would call the `MPI_Wait` function to wait for non-blocking receive to complete.

Let's try to further consolidate these ideas by implementing them in the following exercise!

### 4.3 Rotating information around a ring (non-blocking)

In this exercise you will get to experiment with blocking and non-blocking communication. With the use of non-blocking communications we want to avoid idle time, deadlocks and serializations. This is the second part of a two part exercise.

This is a continuation of the previous exercise with ring communication and when you used blocking communication to solve it. Now you will repeat the exercise but you are now solving the deadlock in an optimal way using non-blocking communication.

~~~c

#include <stdio.h>

#include <mpi.h>

int main()

{

int rank, size;

int snd_buf, rcv_buf;

int right, left;

int sum, i;

MPI_Status status;

MPI_Init(NULL, NULL);

MPI_Comm_rank(MPI_COMM_WORLD, &rank);

MPI_Comm_size(MPI_COMM_WORLD, &size);

right = (rank+1) % size;

left = (rank-1+size) % size;

sum = 0;

snd_buf = rank; //store rank value in send buffer

for(i = 0; i < size; i++)

{

MPI_Send(&snd_buf, 1, MPI_INT, right, 17, MPI_COMM_WORLD); //send data to the right neighbour

MPI_Recv(&rcv_buf, 1, MPI_INT, left, 17, MPI_COMM_WORLD, &status); //receive data from the left neighbour

snd_buf = rcv_buf; //prepare send buffer for next iteration

sum += rcv_buf; //sum of all received values

}

printf ("PE%i:\tSum = %i\n", rank, sum);

MPI_Finalize();

}

~~~

#### Exercise

1. Substitute `MPI_Send` with `MPI_Isend` (non-blocking synchronous send) and put the wait statement at the correct place. Keep the normal blocking `MPI_Recv`. Run the program.

* Do you already have any experience with preventing deadlocks? Which methods have you used in the past? Have you ever thought about serialization?

[](https://mybinder.org/v2/gh/kosl/ihipp-examples/HEAD?filepath=/MPI/Exercise-Ring2.ipynb)

[](https://colab.research.google.com/drive/1gwkAnySSUYXafSEfKClISKBsMVKtrNJr)

### 4.4 One-sided communication

As we have already learnt in the beginning the parallelisation in MPI is based on the distributed memory. This means that if we run a program on different cores, each core has its own private memory. Since the memory is private to each process, we send messages to exchange data from one process to another.

In two-sided (i.e. point to point communication) and collective communication models the problem is that (even with the non blocking) both sender and receiver have to participate in data exchange operations explicitly, which requires synchronization.

In this example we can see when we have the non blocking routine but the problem is that when we call the `MPI_Send` and until the message has been received by the `MPI_Recv`, there is this time in which both the processes have to wait and they can not do anything. Therefore a significant drawback of this approach is that the sender has to wait for the receiver to be ready to receive the data before it can send the data, or vice versa. This causes idle time. To avoid this we use one sided communication.

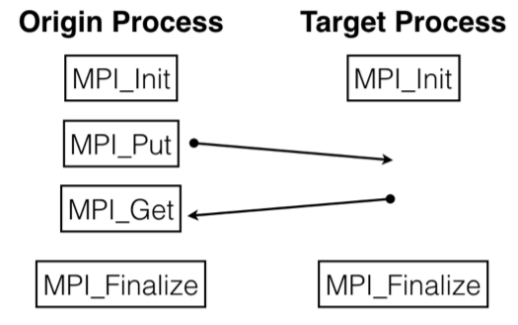

Although MPI is using a distributed memory approach, the MPI standard introduced Remote Memory Access (RMA) routines also called one-sided communication because it requires only one process to transfer data. Simply put, it enables a process to access some data from the memory of the other processes. The idea is that a process can have direct access to the memory address space of a remote process without intervention of that remote process.

So we do not have to explicitly call the *send* and *receive* routines from both processes involved in the communication. One process can just *put* and *get* the data from the memory of another process. This is helpful because the target process can continue executing its tasks, doing its work without waiting for anything. So the most important benefit of one sided communication is that while a process puts or gets data from remote process, the remote process can continue to compute instead of waiting for the data. This reduces communication time and can resolve some problems with scalability of the programs (i.e. on thousands of MPI processes).

In order to allow other processes to have access into its memory, a process has to explicitly expose its own memory to others. This means that for the origin process to access the memory in the target process, the target process has to allow that the memory can be accessed and used. It does this by declaring a shared memory region, also called a window. This window becomes the region in the memory that is available to all the other processes in the communicator allowing them to put and get data from its memory. This window is created by calling the function

~~~c

MPI_Win_create (void *base, MPI_Aint size, int disp_unit, MPI_Info info, MPI_Comm comm, MPI_Win *win);

~~~

The arguments in this function are quite different. They are as follows:

- `base` is the pointer to local data to expose, i.e., the data we would want access to.

- `size` denotes the size of local data in bytes.

- `disp_unit` is the unit size displacements.

- `info` is the information argument. Most often we use `info_NULL`.

- `comm` is the communicator that we know from all the previous functions.

- `win` represents the window object.

And at the end of the MPI application we have to free this window with the function

~~~c

MPI_Win_free (MPI_Win *win);

~~~

So with these functions we create a window around the memory that would be accessible to others. That is why at the end we have to call this `Win_free` function to free this window.

To better understand let's go through a classic example.

~~~c

MPI_Win win;

int shared_buffer[NUM_ELEMENTS];

MPI_Win_create(shared_buffer, NUM_ELEMENT, sizeof(int), MPI_INFO_NULL, MPI_COMM_WORLD, &win);

...

MPI_Win_free(&win);

~~~

So here we define an MPI struct variable `win`. Then we define some data or storage through either dynamic allocation or something similar. Using this buffer we actually then create the window. So in the `MPI_Win_create` you can see that we would like to share this `shared_buffer` buffer. The size here is `NUM_ELEMENTS`. Since each data type is `int`, the displacement becomes, let's say probably 4 bytes wide. The information argument is usually `NULL` and the communicator as always is the `MPI_COMM_WORLD`. Once this is called, this shared buffer can be shared by all the processes by calling the `MPI_Put` and `MPI_Get` routines. Of course, at the end of the application we free the `win` window.

#### `MPI_Put` and `MPI_Get`

To access the data we need the two routines we talked about earlier, the `MPI_Put` and `MPI_Get`. The `MPI_Put` operation is equivalent to a send by origin process and a matching receive by the target process. Let's look at the prototype of these functions which have quite many arguments.

~~~c

MPI_Put (void *origin_addr, int origin_count, MPI_Datatype origin_datatype, int target_rank, MPI_Aint target_disp, int target_count, MPI_Datatype_target_datatype, MPI_Win win)

~~~

In the same manner `MPI_Get` is similar to the put operation, except that data is transferred from the target memory to the origin process. The prototype of this function looks like this

~~~c

MPI_Get (void *origin_addr, int origin_count, MPI_Datatype origin_datatype, int target_rank, MPI_Aint target_disp, int target_count, MPI_Datatype_target_datatype, MPI_Win win);

~~~

We will understand in depth about the arguments of these functions in the following exercise. But before we get into that, another important thing that we need to discuss is the synchronization. If you remember we discussed this concept briefly in the second week when we were learning about the concepts of OpenMP. In one sided communication in MPI, the target process calls the function to create the window in order to give access of its memory to other processes. However, in the case of multiple users it is already quite plain to see that if these users try to simultaneously access this data, that can already lead to some problems. For example, let's say two users access the window to put data using the `MPI_Put` function. This is clearly a race condition that needs to be avoided. This is where synchronization comes into play. So, in order to avoid this before and after each one sided communication function, i.e., `MPI_Get` and `MPI_Put`, we need to use the function

~~~c

MPI_Win_fence (0, MPI_Win win);

~~~

This function actually helps us to synchronize the data in a way that if multiple processes would like to access the same window it makes sure that they go in an order. So, the program will allow different processes to access the window but it will ensure that it is not happening at the same time. So, it is important that the one-sided function calls are surrounded by this fence function.

### 4.5 One-sided communication in a ring

You are already familiar with communication in a ring. In this exercise the goal is to substitute non-blocking communication with one-sided communication.

We want to substitute calls to send and receive routines by using `MPI_Put` or `MPI_Get`. So we have 2 options:

1. The process that previously called send, now calls `MPI_Put`: The send buffer is a local buffer and the receive buffer must be a window.

2. The process that previously called receive, now calls `MPI_Get`: The send buffer is a window and the receive buffer is a local buffer.

For this exercise, you will use the **1.** option. So what you need to do is create a window for the receive buffer and substitute the sending and receiving by calling `MPI_Put` on the process that previously called `MPI_Send`. Also don't forget to do synchronization with `MPI_Win_fence`.

#### Exercise

1. Go to the exercise and fill out the skeleton to create all `rcv_buf` as windows in their processes.

2. Substitute the `Isend`/`Irecv`/`Wait` with `Win_fence`/`Put`/`Win_fence` sequence.

#### Discussion

There are two solutions for substituting non-blocking communication with one-sided communication. Do you have any idea, why would we prefer using `MPI_Put` instead of `MPI_Get`? What is your preferred way, and why?

[](https://mybinder.org/v2/gh/kosl/ihipp-examples/HEAD?filepath=/MPI/One-sided-ring.ipynb)

[](https://colab.research.google.com/drive/1ZT45DqKWiocEHwjDi0ixG7BK1xAhknY1)

### 4.6 Do you understand advanced communication in MPI?

This quiz will test your knowledge on MPI’s advanced communication.

1. Which of the following MPI communication types suspends execution of the calling program until the current communication is completed?

(x) Blocking

( ) Nonblocking

( ) Asynchronous

( ) None of the above

2. A message from a non-blocking send `MPI_Isend` is safe to be accessed immediately after the `MPI_Irecv` command.

( ) True

(x) False

3. What is a valid reason for wanting to use one-sided communication in MPI?

( ) Less synchronization overhead

( ) Lower hardware latency

( ) Easier programming of irregular communication events

(x) All of the above

4. Which of the following steps comes first in setting up MPI one-sided communication?

( ) Starting a communication interval using `MPI_Win_fence`

( ) Defining a transfer with put or get

(x) Initializing a window

( ) The order doesn’t matter

5. If you execute an `MPI_Put`, where is the send and where is the receive buffer?

(x) The `sendbuf` is a local buffer and the `rcvbuf` must be a window.

( ) The `sendbuf` is a window and the `rcvbuf` is a local buffer.

6. What units are used to define the size of a window in a call to `MPI_Win_create`?

(x) Bytes

( ) The units specified by the `MPI_Datatype` argument

( ) Words

7. Immediately after returning from a `MPI_Put call`, it is safe to overwrite the buffer containing the data that was sent.

( ) True

(x) False

8. What is the simplest way to end a one-sided communication interval and re-synchronize, in just one step?

`MPI_Win_ __` ?

Solution:

`MPI_Win_fence`

### 4.7 MPI + threading methods

In this subsection we will build up upon the introduction of OpenMP we did in the first two weeks and we will see how to include it into MPI. There are numerous reasons we need to dwell into this, however the most important is that in High Performance Computing (HPC) the computer systems feature a hierarchical hardware design. So we need to discuss how the multi-core nodes that are connected via a network can be orchestrated efficiently. We will also see where the bottlenecks of each approach lie.

During this subsection we will also discuss or try to find out whether the hybrid code performs better than MPI code and see how it co-relates to whether the communication advantage outcomes the thread overhead, etc. or not. Finally, we will also ask ourselves whether the MPI approach is the best approach and whether there are any other approaches that may offer different speeds or hierarchy within the nodes more efficiently. We will see how the other approaches can provide work load balancing that becomes operative when we are dealing with the large programs that are running on many cores. In the interest of knowing how much effort we will need to make sure that all CPUs are being utilized at maximum efficiency (100%), i.e., there are no sleeping processors, or sleeping GPU, or sleeping threads that are available, so that everything is utilized. This would provide us with the opportunity to explore if there are some other possible approaches for solving these problems more easily and getting the job done in a more efficient way for example with some other language etc.

This is our introduction to parallel programming, meaning that we will just build up on the simple MPI plus threading methods.

To exemplify, let us compare IBM Power8 processors with Intel or AMD, i.e., the classical x64 architecture. We see that the Power8 processor has much more threads per core. So, instead of the usual hyper threading, that we find on our laptops, where we usually have one thread in addition to the core; on a Power8 processor we have, for example eight process cores on one socket, then we may have additional eight threads to be run per core, so that they share cache. Running with many threads raises the performance if we are running an OpenMP program. This implies that the programs and threads share the variables, memory and so on. Hopefully, in the initial OpenMP course that we had in the first two weeks it was quite simple to do that.

#### MPI + OpenMP

The two main threading paradigms we can try are:

- MPI + OpenMP

- MPI + MPI-3 shared memory

MPI+OpenMP is usually a better approach for non-uniform memory architectures and also in cases where we have the many sockets, i.e., cache coherent non-uniform memory. It can be optimised in such a way that we utilize just a smaller amount of MPI threads and the rest are OpenMP. As usual, the prerequisite is that libraries must be thread safe for C, which is not that complicated because C itself utilizes a lot of internal variables that are allocated near by the compute, so the stack or the nearby heap. In the previous week we have been introduced to MPI and we have seen that MPI has a lot of different message passing routines. So, the approach of MPI is to provide all means of communication from simple to extended ways. The OpenMP, or rather the threading model for it, was introduced with MPI-2 so that we can use some threading within the MPI-2. From that library, we are usually using OpenMPI, but there are also some other vendor specific MPI libraries, especially if you buy from prominent vendors. There are tuned MPI libraries that work best on the cluster that you buy, meaning that it takes into account the topology, the latencies and all architectural differences within the MPI library itself.

So, there are three libraries in C that we can initially query:

~~~c

int MPI_Init_thread (int * argc, char ** argv[], int thread_level_required,

int * thread_level_provided);

int MPI_Query_thread (int * thread_level_provided);

int MPI_Is_main_thread (int * flag);

~~~

However, we require certain values prior to this to mention the type or rather the level of threading we can get from. So, the required values are, e.g.:

~~~c

MPI_THREAD_SINGLE

~~~

- Here only one thread will execute the MPI calls.

~~~c

MPI_THREAD_FUNNELED

~~~

- Here only the master thread will make MPI calls.

~~~c

MPI_THREAD_SERIALIZED

~~~

- In this case multiple threads may make MPI calls, but only one at a time.

~~~c

MPI_THREAD_MULTIPLE

~~~

- Here multiple threads may call MPI, without any restrictions.

[](https://mybinder.org/v2/gh/kosl/ihipp-examples/HEAD?filepath=/MPI/Threading-methods.ipynb)

[](https://colab.research.google.com/drive/1EN8Z7EoGvqMFqX_n-46w9iozudNIlIWm)

### 4.8 Calculate Pi! Using MPI_THREAD_FUNNELED

The safest and the easiest way to use threading is to use `MPI_THREAD_FUNNELED`. This level of thread safety assures multithreading, but only the main thread makes the MPI calls (the one that called `MPI_Init_thread`). All MPI calls are made by the master thread, outside the OpenMP parallel regions or in OpenMP master regions.

This example notebook shows how to calculate the value of Pi by solving this integral approximation.

$$\pi = \int_{0}^1 \frac{4}{1+x^2}~dx \approx \sum_{i=0}^{n-1}f(x_i+h/2)h$$

You have already computed this with OpenMP and MPI in the previous weeks. We will use both approaches in this example. The goal is to minimally use MPI for inter-node communication and inside the node to do everything by shared memory computing with OpenMP. The complete code is shown below.

~~~c

#include <omp.h>

#include <mpi.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#define N 1000000

int main(int argc, char *argv[])

{

int rank;

int size;

int provided;

double subsum = 0.0;

MPI_Init_thread(&argc, &argv, MPI_THREAD_FUNNELED, &provided);

MPI_Comm_rank(MPI_COMM_WORLD, &rank);

MPI_Comm_size(MPI_COMM_WORLD, &size);

int nthreads = 2;

omp_set_num_threads(nthreads);

#pragma omp parallel

{

int tid = omp_get_thread_num();

printf("Thread %d within rank %d started.\n", tid, rank);

#pragma omp for reduction(+:subsum)

for(int i = rank; i < N; i += size*nthreads)

{

double x = (i+0.5)/N;

subsum += 4/(1 + x*x);

}

}

double sum;

MPI_Reduce(&subsum, &sum, 1, MPI_DOUBLE, MPI_SUM, 0, MPI_COMM_WORLD);

if (rank == 0)

printf("pi = %.10lf\n", sum*nthreads/N);

MPI_Finalize();

return 0;

}

~~~

When we have threading, it is important to think about how to split up the workload. You can see how the workload is split with this line below, so we follow the same principles asked by MPI. If we have `nthreads`, then we need to increase the jump to the next chunk by the value of `size*nthreads`. Each chunk is computed this way:

~~~c

for(int i = rank; i < N; i += size*nthreads)

~~~

The collection of `subsum`, that is actually a shared variable within the threads and starts for each MPI process as `0.0`, is collected from each thread in one rank, so we get `subsum` for each MPI process at the end of OpenMP parallel region. After that the master thread reduces this `subsum` together as `sum` with MPI.

We compile and run this program on 3 processes and by setting 2 threads inside the code we have 6 threads in total within 3 ranks (rank 0, 1 and 2).

~~~c

mpicc -fopenmp pi-hybrid.c && mpirun -n 3 --allow-run-as-root a.out

~~~

Have a look at the code and run it in the notebook at the end of this article.

#### Learning outcomes for the exercise

This program was done in the first way of threading methods (MPI + OpenMP).

* This way of parallelization that we just did in the notebook example fits nicely with most OpenMP models.

* Expensive loops are parallelized with OpenMP and that is faster. You can utilize many of the processor cores, so doubling the number of threads, instead of cores. So, running programs this way surely has some potential.

* Communication and MPI calls among loops.

* Eliminates need for true “thread-safe” MPI.

* Parallel scaling efficiency may be limited (Amdahl’s law) by `MPI_THREAD_FUNNELED` approach.

* Moving to `MPI_THREAD_MULTIPLE` does come at a performance price (and programming challenge).

[](https://mybinder.org/v2/gh/kosl/ihipp-examples/HEAD?filepath=/MPI/Compute-Pi-Funneled.ipynb)

[](https://colab.research.google.com/drive/1CvsmJmEEUMuEC609xneBvgsY5xuioTlF)

### 4.9 Hybrid MPI

#### Hybrid MPI + OpenMP Masteronly Style

We saw in the previous exercise that the scaling efficiency may be limited by the Amdahl's law. This means that, of course, even though all of the computation is actually parallelised, we might still have large chunks of serial code present. For example, the serial code is the code that follows after `#pragma omp for reduction` in the previous example. So, the reduction clause is a serial portion of code even though it utilizes parallel threads. But this is the last command and the following `MPI_Reduce` is actually collective communication as we have already learnt.

If we are doing something like this in the loop, we will surely get a definite amount of serial code, meaning that we will anyway be limited by the Amdahl's law in scaling. This directly implies that we cannot utilize the abundant thousands or more cores (even a million) that are popping out each day on new and recent hardware.

An efficient solution to these problems would be an overlap. Some kind of region where we could do MPI simultaneously with OpenMP in order to overcome these communication issues. This can be achieved by the Hybrid MPI + OpenMP Masteronly Style. There are quite a few advantages of using this hybrid approach, however, the most prominent are that:

- there is no message passing inside of the SMP nodes and

- there are no topology problems.

An efficient example to explain the need and efficiency of this is if we are doing a ray tracing in a room for example. The problem of ray tracing is that the volume, that we are describing, is quite complex. So, let's say if we have to do the light tracing and reflections that we see from the lighting and so on, we would need to compute the parameters for each ray. This is already several gigabytes of memory and if we have just 60 GB of memory per node, then we are limited by memory to solve the problem. So, we cannot do large problems with many cores because each core in MPI actually gets its own problem inside it. There is no sharing of the problem among the threads, processes or cores. We could usually solve this problem fairly easily by using MPI + OpenMP.

These kind of problems, which take a lot of memory since they are complex because of the description of environment and so on are best done with MPI + OpenMP.

#### Calling MPI inside of OMP MASTER

If we would like to do communication, then it is usually best to do OMP master thread. This ensures that only one thread communicates with MPI. However, we will still need to do some synchronization. As we learnt in the previous weeks about synchronization, is that sometimes in parallel programming, when dealing with multiple threads running in parallel, we want to pause the execution of threads and instead run only one thread at the time. Synchronization means that whenever we do MPI, all threads will need to stop at some point and do the barrier.

In OpenMP the MPI is called inside of a parallel region, with `OMP MASTER`. It requires `MPI_THREAD_FUNNELED`, and we saw in the previous subsection this implies that only the master thread will make MPI calls. However, we need to be aware that there isn’t any synchronization with `OMP MASTER`! There is no implicit barrier in the master workshare construct. Therefore, with `OMP BARRIER` it is necessary to guarantee, that data or buffer space from/for other threads is available before/after the MPI call! The barrier is necessary to prevent data races.

Fortran directives:

~~~Fortran

!$OMP BARRIER

!$OMP MASTER

call MPI_Xxx(...)

!$OMP END MASTER

!$OMP BARRIER

~~~

C directives:

~~~c

#pragma omp barrier

#pragma omp master

{

MPI_Xxx(...);

}

#pragma omp barrier

~~~

We can see above that this implies that all other threads are sleeping, and the additional barrier implies the necessary cache flush!

Through the following exercise we will see why the barrier is necessary.

#### Example with `MPI_recv`

In the example, the master thread will execute a single MPI call within the `OMP MASTER` construct, while all the other threads are idle. As illustrated, barriers may be required in two places:

* Before the MPI call, in case the MPI call needs to wait on the results of other threads.

* After the MPI call, in case other threads immediately need the results of the MPI call.

Code in Fortran:

~~~Fortran

!$OMP parallel

!$OMP do

do i=1, 1000

a(i) = buf(i)

end do

!$OMP end do nowait

!$OMP barrier

!$OMP master

call MPI_Recv(buf, …)

!$OMP end master

!$OMP barrier

!$OMP do

do i=1, 1000

c(i) = buf(i)

end do

!$OMP end do nowait

!$OMP end parallel

~~~

Code in C:

~~~c

#pragma omp parallel

{

#pragma omp for nowait

for (i = 0; i < 1000; i++)

a[i] = buf[i];

#pragma omp barrier

#pragma omp master

{

MPI_Recv(buf,....);

}

#pragma omp barrier

#pragma omp for nowait

for (i = 0; i < 1000; i++)

c[i] = buf[i];

}

~~~

### 4.10 Quiz on Hybrid programming with OpenMP and MPI

Do you understand how OpenMP can be included and used with MPI? Test your understanding of this topic with this quiz.

1. An MPI process is generally single-threaded unless the code has been augmented with multithreading directives or library calls.

(x) True

( ) False

2. If `MPI_Init_thread` returns `MPI_THREAD_FUNNELED`, MPI messages can only be passed between main threads.

(x) True

( ) False

3. Which argument to `MPI_Send` may be used to identify the destination thread?

( ) rank

( ) count

(x) tag

( ) communicator

4. MPI messages can be passed between any two threads, provided each is enclosed in an `omp single` construct, when `MPI_Init_thread` returns what value?

( ) `MPI_THREAD_SINGLE`

( ) `MPI_THREAD_FUNNELED`

(x) `MPI_THREAD_SERIALIZED`

( ) `MPI_THREAD_MULTIPLE`

### 4.11 Derived data type

So far we have learnt to send messages that were a continuous sequence of elements and mostly of the basic data types such as `buf`, `count` etc. In this section we will learn how to transfer any combination of data in memory in one message. We will learn to communicate strided data, i.e., a chunk of data with holes between the portions, and how to communicate various basic data types within one message.

So, if we have many different types of data types such as `int`, `float` etc. with gaps, how would we perform communication in one way with one command? To do this we would first of all need to start by describing the memory layout that we would like to transfer. Following this, the processor that compiled the derived type layout will then do the transfer for us in the loop in a correct way. This can even be achieved with all kinds of broadcasts.

Since we would not need to copy data into a continuous array, to be transferred as a single chunk of memory, there is no waste of memory bandwidth in such a way. Therefore derived types are usually structures of:

- vectors

- subarrays

- structs

- others

Or they could be simple types that are being combined into one data layout without the need of copying into one piece to be transferred efficiently or in one block of message. It is not uncommon to have messages of size over 60 or more kilobytes. In cases where we would like to transfer the results of some programs that could be larger files, actually this is the most efficient way to do it. Of course, there are other alternatives such as writing the results into a file and later opening and reading the file. Quite often the codes do not actually return results, but they just write their results into a file, and eventually we'll need to combine the results into one representation. This is quite similar to how we do it in a profiler or tracer, creating a file for each processor. So, it is already quite easy to understand that if we are debugging a code with two thousand cores (which is not that big) we will easily end up with two thousand files to be read that need to be interpreted and that will definitely take some time. We will learn about it more in the following subsections of parallel I/O.

#### Derived data types — type maps

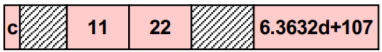

A derived data type is logically a pointer to a list of entries. However, once this data type has been saved somewhere, it is not communicated over the network. When the need comes we just use this type simply as it would be a basic data type. However, the only prerequisite is that for each of these data types we need to compute the displacement. Quite obviously MPI does not communicate these displacements over the network.

| Basic data type | Displacement |

| :-----------------------: | :---------------: |

| `MPI_CHAR` | 0 |

| `MPI_INT` | 4 |

| `MPI_INT` | 8 |

| `MPI_DOUBLE` | 16 |

Here you can see the description of the memory layout and the displacements. For example, `MPI_INT` can be displaced for four or eight bytes and `MPI_DOUBLE` is displaced for sixteen bytes and so on. A derived data type describes the memory layout of, e.g., structures, common blocks, subarrays and some variables in the memory etc.

#### Contiguous Data

This is the simplest derived data type as it consists of a number of contiguous items of the same data type.

In C we use the following function to define it:

~~~c

int MPI_Type_contiguous (int count, MPI_Datatype oldtype, MPI_Datatype *newtype)

~~~

#### Committing and Freeing a data type

Before a data type handle is used in message passing communication, it needs to be committed with `MPI_TYPE_COMMIT`. This needs to be done only once by each MPI process. When we commit, it implies that data type recites a description inside, that can be used similar to a basic data type. However, if at some point this changes or we would like to release some memory, or if we will not use it anymore, we may call `MPI_TYPE_FREE()` to free the data type and its internal resources.

The routine used is as follows:

~~~c

int MPI_Type_commit (MPI_Datatype *datatype);

~~~

#### Example

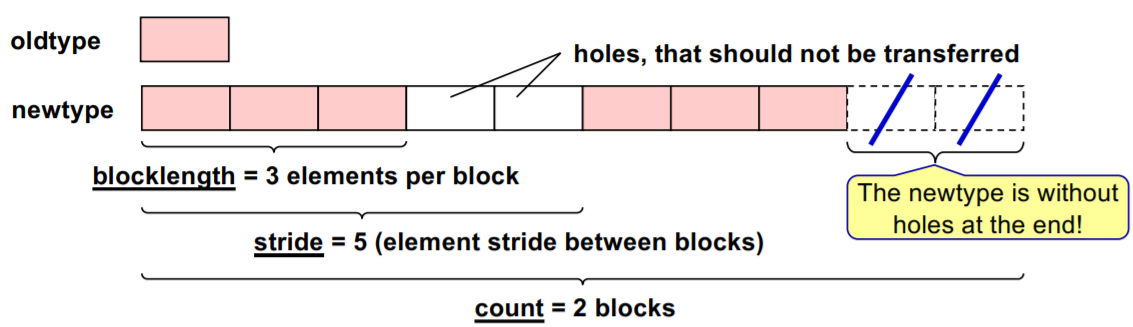

Here in this example we can see the real need for derived data types.

~~~c

struct buff_layout {

int i_val[3];

double d_val[5];

} buffer;

~~~

We have a structure of fixed size integer values and also some double values. So, this is one single data that we would like to describe in a data type so that we could then send this structure in one command, i.e., send or receive. We do not really care whether it is blocking or non-blocking at this point. So, in order to achieve this we describe the data type called `buff_datatype`. This is actually a name that we commit to this type.

~~~c

array_of_types[0] = MPI_INT;

array_of_blocklengths[0] = 3;

array_of_displacements[0] = 0;

array_of_types[1] = MPI_DOUBLE;

array_of_blocklengths[1] = 5;

array_of_displacements[1] = …;

MPI_Type_create_struct (2, array_of_blocklengths, array_of_displacements, array_of_types, &buff_datatype);

MPI_Type_commit(&buff_datatype);

~~~

So, we push the type after we create it and compile it to the MPI subsystem. Afterwards, the subsystem refers to that data type inside the system itself and knows how to convert, the integers etc. with the type that we use inside.

~~~c

MPI_Send(&buffer, 1, buff_datatype, …)

~~~

Of course, there can also be some kind of gaps that we would not actually see if we are using some other languages such as Fortran and sometimes we even have memory alignments for it. So, there may be a gap of one integer at the start. But this is not an error on our part but it is just an adjustment, like some kind of performance adjustment, so that the next array starts at the location that is the multiple of four. So, while describing such an array MPI knows how to do it most efficiently.

### 4.12 Derived data type

In this exercise you will pass data around a ring with a derived data type instead of an integer or an array like we did so far. Your send and receive buffer will be a struct with two integers.

#### Exercise

You will use a modified pass-around-the-ring program which already includes a struct with two integers. In the exercise you will:

1. Produce a new data type that can be used as a buffer with the routines that you have learned in the previous step.

2. Initialize the struct integers with `rank` and `10*rank`. Therefore we will pass around two values and calculate two separate sums.

3. Use the new data type in the send and receive routine calls. Currently, the data is send with the description `snd_buf, 2, MPI_INTEGER` which you must modify by using a derived data type and with a type map of “two integers”.

[](https://mybinder.org/v2/gh/kosl/ihipp-examples/HEAD?filepath=/MPI/Derived-datatypes.ipynb)

[](https://colab.research.google.com/drive/1gLUk3OPO01kvWxQ_LpaPI220crE7zZzx)

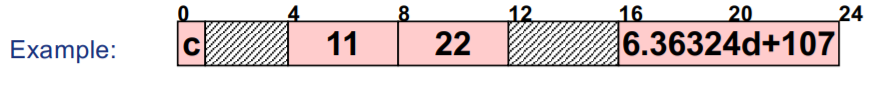

### 4.13 Layout of struct data types

#### Vector data types

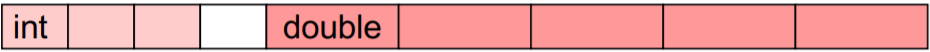

What we learnt so far in the previous subsection and the exercise were more like continuous vectors. Sometimes we would need to communicate vectors with holes that we do not want to be transferred. This implies that we would not send each element but just selected elements or sequence of elements. Therefore the block length and the offset of each can be used to create a *stride*. When we want to communicate just a portion of a continuous chunk of memory the destination and source may not be the same. Usually, we have one element to receive the results back from the array of cluster. We saw in the previous Pi example how the integrals were collected back, so that we see the complete sums for which we could use such vector data types.

**Image courtesy: Rolf Rabenseifner (HLRS)**

We use the following routine for vector data types:

~~~c

int MPI_Type_vector (int count, int blocklength, int stride, MPI_Datatype oldtype, MPI_Datatype *newtype)

~~~

The structure of the routine is similar to most we have learnt previously:

- `count` suggests how many elements

- `blocklength` is the number of elements per block

- `stride` is the offset to the next portion of the result

- `Datatype` - we can have only one data type here and it could be a derived one. Of course, we can communicate a strided array of slots and integers and subsequently we will get a `newtype` created that can be used in send and receive routines.

#### Struct data type

So, we could have old types that are of different sizes and then we could combine two old types into a single vector or a block that can be also with holes and these holes will not be communicated. This is a more prevalent way to describe the type instead of doing what we saw earlier. The previous method is not optimal for large numbers of such kinds of arrays. In such cases we use the struct data types, so that communication is executed in the correct way.

The routine for this data type looks like

~~~c

int MPI_Type_create_struct (int count, int *array_of_blocklengths, MPI_Aint *array_of_displacements, MPI_Datatype *array

~~~

This is how memory layout of struct data types could look like with gaps inside that we don't actually want, but are imposed by the compiler itself or the underlying operating system or hardware processor.

Let's assume that we have the following parameters:

~~~

count = 2

array_of_blocklengths = ( 3, 5 )

array_of_displacements = ( 0, addr_1 – addr_0 )

array_of_types = ( MPI_INT, MPI_DOUBLE )

~~~

In this case the prototype for fixed memory layout of the struct data type would be as follows:

~~~c

struct buff {

int i_val[3];

double d_val[5];

}

~~~

### 4.14 Computing displacements

We actually need to compute the displacements. So, if we would like to see the size of each structure in bytes, that would need to be prescribed as a buffer, the displacement needs to be known.

In MPI1 before, we started with derived types. We can see some differences between MPI3 and MPI1, similar to the kind of problems that Fortran had. These issues are now resolved with MPI3.1. Now, there is a deprecated way of doing upper and lower bound for the structure. This is the recommended way how to compute the displacement from one type to another.

The standard procedure for obtaining the displacement is

~~~c

array_of_displacements[i] := address(block_i) – address(block_0)

~~~

And in order to get the absolute address we would need the routine

~~~c

int MPI_Get_address (void* location, MPI_Aint *address)

~~~

In the MPI3.1 version the relative displacement can be calculated as the difference between absolute address 1 and absolute address 2 and the new absolute address can be denoted as the sum of the existing absolute address and the relative displacement. So

~~~c

Relative displacement:= absolute address 1 – absolute address 2

~~~

with the routine that looks like

~~~c

MPI_Aint MPI_Aint_diff (MPI_Aint addr1, MPI_Aint addr2)

~~~

and

~~~c

New absolute address := existing absolute address + relative displacement

~~~

with the routine that looks like

~~~c

MPI_Aint MPI_Aint_add (MPI_Aint base, MPI_Aint disp)

~~~

#### Example

In this example we see how we compute the address. The `Aint` address variable or `disp` displacements could be computed by prescribing the start of the first element. The `snd_buf.i[0]` is actually the correct way of defining that address.

~~~c

struct buff {

int i[3];

double d[5];

} snd_buf;

MPI_Aint iaddr0, iaddr1, disp;

MPI_Init(NULL, NULL);

// the address value &snd_buf.i[0] is stored into variable iaddr0

MPI_Get_address(&snd_buf.i[0], &iaddr0);

MPI_Get_address(&snd_buf.d[0], &iaddr1);

disp = MPI_Aint_diff(iaddr1, iaddr0);

MPI_Finalize();

~~~

### 4.15 Which is the fastest neighbor communication with strided data?

What do you think: which is the fastest neighbor communication with strided data?

- While using derived data type handles

- Copying the strided data in a contiguous scratch send buffer, communicating this send buffer into a contiguous recv buffer and copying the recv buffer back into the strided application array

And which of the communication routines should be used?

### 4.16 Quiz on derived data types

This quiz tests your knowledge of user derived data types.

1. Which of the following general data types assumes that the stride is equal to 1?

(x) Contiguous

( ) Vector

( ) Struct

2. Which of the following general data types may consist of more than one basic data type?

( ) Contiguous

( ) Vector

(x) Struct

3. If you have an array of a structure in your memory, how would you describe this?

Using function `MPI_ __` for the structure and the `__` argument in the MPI communication procedure for the size of the array.

Solution:

Using function `MPI_Type_create_struct` for the structure and the `count` argument in the MPI communication procedure for the size of the array.

4. Which additional MPI procedure call is required, before a newly generated data type handle can be used in message passing communication?

( ) `MPI_Type_contiguous`

( ) `MPI_Type_create_resized`

(x) `MPI_Type_commit`

( ) `MPI_Type_free`

### 4.17 Pass-around-the-ring exercise

In this exercise you will pass data around a ring with a derived data type instead of an integer or an array like we did so far. Your send and receive buffer will be a struct with one integer and one floating point.

#### Exercise

You will use a modified pass-around-the-ring program which already includes a struct with one integer and one floating point. In the exercise you will fill out the blank spaces and modify the call routines to use the new data type.

1. Set MPI data types for sending and receiving partial sums with the routines that you have learned in the previous step. You should use `MPI_Type_create_struct`. You are using the same fixed memory layout for send and receive buffer.

2. Initialize the struct integers with `rank` and `10*rank`. Therefore we will pass around two values and calculate two separate sums: rank integer sum and rank floating point sum.

3. Use the new data type in the send and receive routine calls.

[](https://mybinder.org/v2/gh/kosl/ihipp-examples/HEAD?filepath=/MPI/Derived-datatypes-2.ipynb)

[](https://colab.research.google.com/drive/1ZelmLf5ls947WirRkrBMRt2eOmNarmAP)

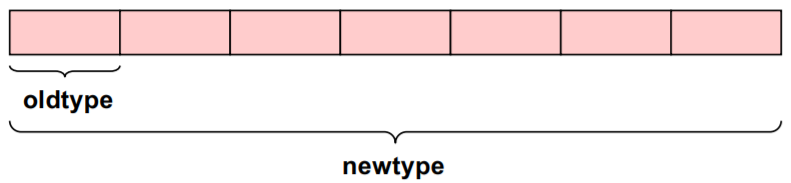

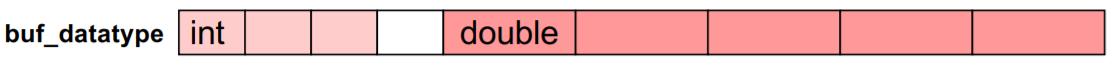

### 4.18 Brief explanation of size, extent and alignment rules

Before we go further into the Parallel file I/O we need to get some basic knowledge about the terminology of size, extent, true extent etc. and get some background about the alignment rules.

- Size is the number of bytes that have to be transferred.

- Extent represents the spans from first to last byte including all the holes.

- True extent spans from first to last true byte but in this case excluding holes at the beginning and the end.

For most of the basic data types the Size = Extent = number of bytes is used by the compiler. This can be seen easily in the following image.

**Image courtesy: Rolf Rabenseifner (HLRS)**

Extent, alignment and holes can be a problem for some compilers or architectures, especially if these are optimised. However, MPI3 has fixed a lot of these problems by introducing new interfaces that solve certain issues and offer a better usable interface. However, in the standard these parameters always hold true:

- There are automatic holes at the end for necessary alignment purpose.

- There can be additional holes at the beginning and by `lb` and `ub` markers: `MPI_TYPE_CREATE_RESIZED`.

- And as mentioned already, for basic data types: Size = Extent = number of bytes is used by the compiler.

#### Alignment rule, holes and resizing of structures

At times, the compiler might add additional alignment holes either within a structure (for example between a float and a double) or at the end of a structure (i.e., after elemets of different sizes). However, alignment holes are important at the end when using an array of structures!

To imply this, if an array of structures (in C/C++) or derived types (in Fortran) should be communicated, then it is recommended that we create a portable data type handle and additionally apply `MPI_TYPE_CREATE_RESIZED` to this data type handle.

Quite often, due to the alignment gaps the holes may cause a significant loss of bandwidth. Technically by definition, MPI is not allowed to transfer the holes. Therefore, we need to fill holes with dummy elements.

Sometimes certain problems might arise, such as the MPI extent of a structure is not the same or equal as the real size of the structure. This could be due to the fact that MPI adds alignment holes at the end because the MPI library has wrong expectations about compiler rules that are

- For a basic data type within the structure

- For the allowed size of the whole structure (e.g., multiple of 16)

To rectify this problem we can call

~~~c

MPI_Type_create_resized(...); //with lb=0 and

new_extent = sizeof(one structure);

~~~

~~~Fortran

integer(kind=MPI_ADDRESS_KIND) :: address1, address2, lb, new_extent

call MPI_Get_address(my_struct(1), address1, ierror)

call MPI_Get_address(my_struct(2), address2, ierror)

new_extent = MPI_Aint_diff(address2, address1)

lb = 0

call MPI_Type_create_resized(&old_struct_type, lb, new_extent, correct_struct_type, ierror)

~~~

#### Example: Correcting problem with array of structures

This is an example program where we have an array of structures containing a double and an integer. A new data type handle is implemented by resizing the old one and doing the commit. We use the new resized data type handle in the send and receive call routines.

These are the important new additions to the code:

~~~c

MPI_Datatype send_recv_type, send_recv_resized;

...

MPI_Type_create_struct(2, ..., &send_recv_type);

MPI_Type_create_resized(send_recv_type, (MPI_Aint) 0, (MPI_Aint) sizeof(snd_buf[0]), &send_recv_resized);

MPI_Type_commit(&send_recv_resized);

~~~

~~~Fortran

integer(kind=MPI_ADDRESS_KIND) :: first_var_address, second_var_address, lb, extent

integer :: send_recv_type, send_recv_resized

...

call MPI_Type_create_struct(2, ..., send_recv_type, error)

call MPI_Get_address(snd_buf(1), first_var_address, error)

call MPI_Get_address(snd_buf(2), second_var_address, error)

lb = 0

extent = MPI_Aint_diff(second_var_address, first_var_address)

call MPI_Type_create_resized(send_recv_type, lb, extent, send_recv_resized, error)

call MPI_Type_commit(send_recv_resized, error)

~~~

[](https://mybinder.org/v2/gh/kosl/ihipp-examples/HEAD?filepath=/MPI/Correcting-array-of-structures.ipynb)

[](https://colab.research.google.com/drive/18vR8NGQuEpwdJcNm6XFOb47U334JUH41)

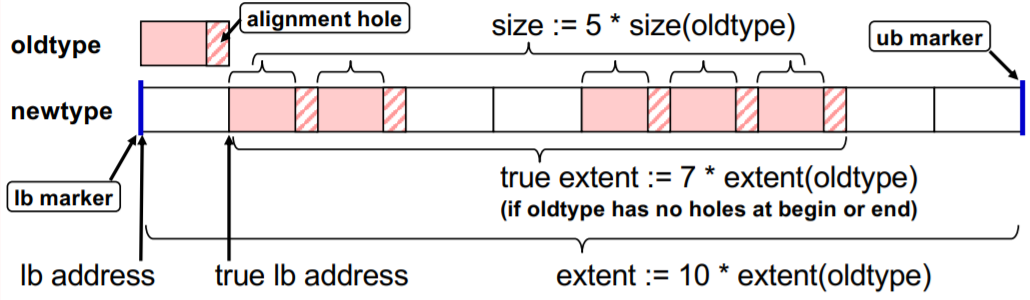

### 4.19 Parallel file I/O

Many parallel applications need a coordinated parallel access to a file by a group of processes and at times this could be simultaneous. Frequently all the processes may read/write many (small) non-contiguous pieces of the file, i.e., the data may be distributed amongst the processes according to a partitioning scheme. Writing of the results can be done by all compute nodes at once or even compute cores, writing their own portion of the result and having a huge amount (not by size but by the number) of files is very inefficient in such a way.

In this subsection we are addressing classic File I/O and figuring out when we will be using such kind of I/O and for what purposes. We will also observe if there are any other means to do the same thing. Although there are some object file systems also being used in HPC that do not have a classical file layout and we would need to address such objects or chunks of data that are saved into the file system differently, but we will not address these issues here.

There are quite a lot of problems with file systems in high performance computing. Usually, large codes read large data as input and write large data as output. Since many computations are done iteratively, meaning that they are convergent or they progress the solution in a stepwise manner, the storage can be occupied quite fast. For example, if we are simulating a system of particles in HPC or solving fluid equations or doing some kind of time evolution simulation, we would need to store large amounts of data. So, finding petabytes of disks to be full is not uncommon. A lot of data being saved to the disk should not impact the computation, i.e., if we would like to store results into a disk, it should not impact communication and the overall progress of the code.

This is where the Parallel File I/O comes into play, so that we could save results for example by a timestep, or by processors that are already combined together at progress or computation time.

It is quite difficult if we have a running large code that would like to store all the resources or at least the state of a current simulation. Since quite often it is not just the results that are being saved, but also intermediate results or steps at selected times. So, for example, if a simulation crashes, it can be restarted at that point. This is problematic owing to the fact that the usual scheduling on clusters limits the time of how long one code can run and usually that is actually limited to 24 hours and for some clusters it could be an even shorter time. In any case, where we would have a code that we would like to run for a month it would be meticulous if it needs to stop at some point and we can start from the previous state and continue simulation. This would imply that somehow we need to store the last state into the disk and restart from that so called check point or saving the current state.

This is overcome with Parallel file I/O that lowers the number of files and performs the writing in an efficient way. This can be achieved because the parallel file systems allow us to write to several file servers at the same time through metadata orchestrator. When we open a file, the metadata server informs the node (which is handling the network file system) to which of the available data file or targets do they need to send the data. If there are thousands of compute nodes, then there are, let's say, at least dozens of file servers that handle hundreds of disks to allow parallel file transfers.

Thus, at any given time, many of compute nodes are sending network files over through the file server. Therefore in Parallel File I/O we could actually write chunks of the single file for several of those compute nodes. Reading and writing files is analogous to sending and receiving messages respectively which we have learnt earlier. The only exception is that this is a persistent memory, meaning that such kind of writing has to be done correctly. Additionally, for codes that do computation in parts, meaning that if we have a code that does domain decomposition before we start, then some of the compute nodes or compute cores already know which portion of the file needs to be read in order to start processing. In this case having a single file for saving the timestep is something that is very useful for large clusters that would like to handle millions of files, with the minimum number of needs.

This allows us to use parallel I/O functions that do not block computation, allowing us to put overlapped computation and reading/writing through it. This is possible through some standard formats that look like a readable file at the end; not just by the code that has written it, but also for general purpose file readers. For example, a prominent format for the file that is parallel is HDF, i.e., hierarchical data format. It is used quite often by many codes and it provides MPI Parallel I/O. Consequently, instead of learning what we can do with the Parallel I/O, it would be more efficient if we learn how to do MPI I/O with HDF format in a parallel way. The MPI I/O features provided by MPI standards are actually part of hierarchical data formats and other net CDF or similar formats. To summarise, the MPI I/O features are to provide a high-level interface to support:

- data file partitioning among processes

- transfer global data between memory and files (collective I/O)

- asynchronous transfers

- strided access

Some basic principles of MPI I/O are:

- an MPI file contains elements of a single MPI datatype (etype)

- partitioning the file among processes with an access template (filetype)

- all file accesses transfer to/from a contiguous or non-contiguous user buffer (MPI datatype)

- nonblocking / blocking and collective / individual read / write routines

- individual and shared file pointers, explicit offsets

- binary I/O

- automatic data conversion in heterogenous systems

- file interoperability with external representation

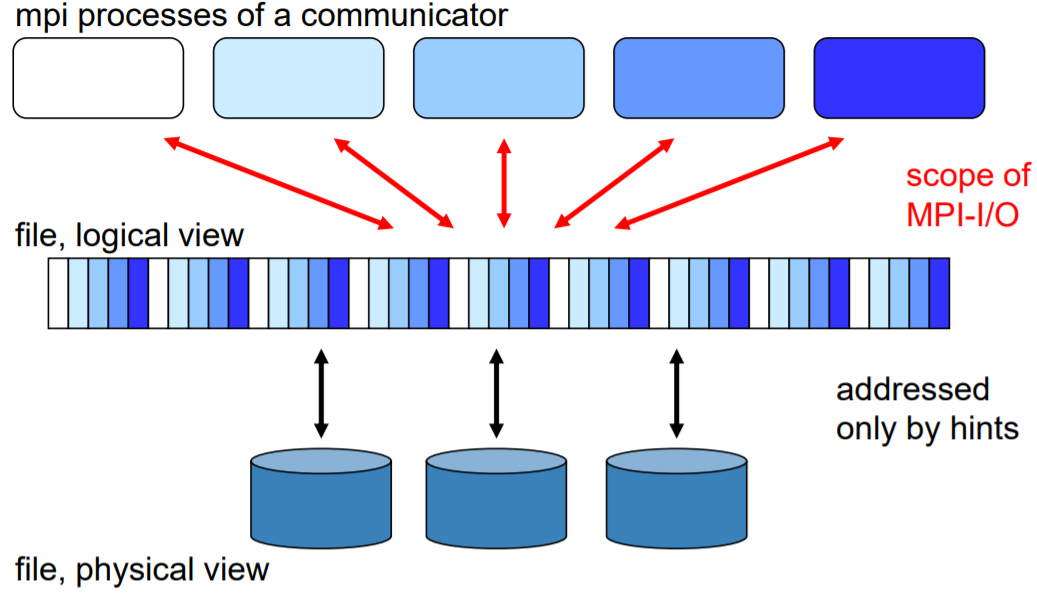

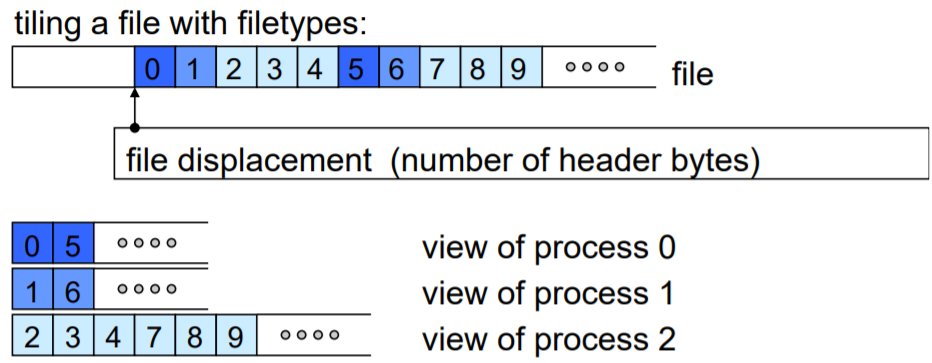

**Image courtesy: Rolf Rabenseifner (HLRS)**

So, we will learn these principles of MPI I/O to see that we could create a file that perhaps looks like a single file. However, in reality there are many of the processes that start work on different nodes but actually open the same file and write the results into one physical file, while in a logical way there may be gaps that are not allowed to be used or to be written. This is because the striking from a logical way to a physical way is done in such a way that we already know what place we can save our portion of the file to.

**Image courtesy: Rolf Rabenseifner (HLRS)**

Simply put, we need to know the size of one chunk and the file system just needs to move the file pointer to the correct place where it writes to. This is quite simple because even the serial file I/O allows us to move backwards and forwards in the file, if it is in a binary way so that we know with what offset we can expect something. In this case we could have a single file that can create many cores writing at the same time to the different servers and in the end it looks like a single file for you. To ease out these terms:

- A file is an ordered collection of typed data items.

- etypes refer to the unit of data access and positioning / offsets that can be any basic or derived data type. It is usually with non-negative, monotonically non-decreasing, non-absolute displacement and is generally contiguous but it does not need to be typically same for all processes.

- filetypes are the basis for partitioning a file among processes. They define a template for accessing the file. They are usually different for each process.

- Each process has its own *view* that is defined by a displacement, an etype and a filetype. The file type is repeated, starting at displacement.

- An offset is the position relative to the current view in units of etype.

To open an MPI file we use the routine

~~~c

MPI_FILE_OPEN(comm, filename, amode, info, fh)

~~~

and the parameters in this routine are:

- `MPI_FILE_OPEN` is collective over `comm`

- filename’s namespace is implementation-dependent

- `filename` must reference the same file on all processes

- process-local files can be opened by passing `MPI_COMM_SELF` as `comm`

- returns a file handle `fh`

However, the default is:

- displacement = 0

- etype = `MPI_BYTE`

- filetype = `MPI_BYTE`

We prescribe the way of displacements that is needed.

Sometimes we might need to close or delete a file. We use the following routines:

~~~c

//Close: collective

MPI_FILE_CLOSE(fh)

~~~

~~~c

//Delete

MPI_FILE_DELETE(filename, info)

~~~

However, if access mode `amode=MPI_DELETE_ON_CLOSE` was specified in `MPI_FILE_OPEN`, then the file is obviously automatically deleted on close.

We will learn further about the MPI I/O principles through a simple example.

### 4.20 Four processes write a file in parallel

In this exercise your program should write a file in parallel using four processes.

#### Exercise

1. Each process should write its rank (as one character) ten times to the offsets = `rank + i * size`, where `i=0..9`.

2. Each process uses the default view.

#### Tip

When checking if your file is correctly written, you should:

- use `ls -l` to look at the number of bytes and it should be 40 bytes

- use `cat my_file` to look at the content of your file and the expected result is `0123012301230123012301230123012301230123`

- use `rm my_file` to remove the file before running the program again because it will rewrite the file

[](https://mybinder.org/v2/gh/kosl/ihipp-examples/HEAD?filepath=/MPI/IO/Write-file-parallel.ipynb)

[](https://colab.research.google.com/drive/114xdCs1UIvMQefkdaWlP2Ss-U5AfJO2B)

### 4.21 Week 4 wrap-up

In Week 4 we tried to present advanced communication types in MPI and how to combine OpenMP and MPI in a hybrid programming paradigm. Also some advanced approaches, such as user derived datatypes and parallel file I/O principles were discussed. As before, the hands on examples served to show how to use this techniques as efficiently as possible.

Please, discuss the advanced principles shown in this week and try to summarize their potential in general or maybe specifically for your applications.

Have you found the advanced content of Week 4 interesting and useful?

For further reading you can find a very complete MPI training course at the [HLRS online training course recordings / self-study](http://www.hlrs.de/training/par-prog-ws/)

and especially the password-free [MPI training course material](https://www.hlrs.de/training/par-prog-ws/MPI-course-material),

which always contains the actual version of HLRS' MPI course (Courtesy: Rolf Rabenseifner, HLRS).

Sign in with Wallet

Sign in with Wallet