---

title: Rust-Python FFI & multilanguage system debugging! BlogPost

description: Rust-Python FFI!

---

# Rust-Python bridging! Case study of FFI issues and solutions.

Writing a rust library usable in multiple languages is not easy...

This blogpost recollects things I have encountered while building [wonnx](https://github.com/webonnx/wonnx) and [dora-rs](https://github.com/dora-rs/dora). I am going to use Rust-Python FFI through `pyo` as an example knowing that you can extrapolate those issues to other languages.

There is going to be 6 parts: FFI, debugging, memory management, race condition, tracing, and distribution.

## FFI (Foreign Function Interface) design

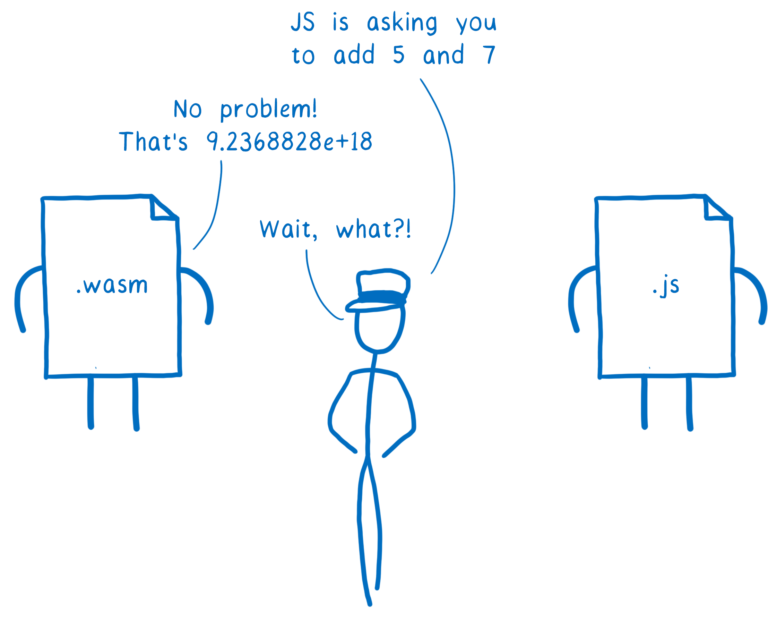

A foreign function interface (FFI) is an interface used to share data from different languages. When bridging different languages, it's the FFI that is going to make the two languages interpret the data.

By default, python might not know what a Rust `u16` is, so an interface is needed to make the two languages communicate.

> Image from [WebAssembly Interface Types: Interoperate with All the Things!](https://hacks.mozilla.org/2019/08/webassembly-interface-types/)

Building interfaces might not be easy as, you often have to use the C-ABI as it is often the common denominator.

Thankfully, there are FFI libraries that create interfaces for you and you can just focus on the important stuff such as the logic and so on. One example of such FFI library is [`pyo3`](https://github.com/PyO3/pyo3).

### Python and [`pyo3`](https://github.com/PyO3/pyo3)

`pyo3` is probably the most used Rust-Python binding and creates those FFI for you. All you have to do is wrap your function with a `#[pyfunction]` and after some simple step, it's going to be usable in Python.

In this blog post, I'm going to build a toy Rust-Python project with `pyo3` to illustrate the issues I have faced, and you can extrapolate those findings to your own bindings.

You can try this blogpost at home by forking the [blogpost repository](https://github.com/haixuanTao/blogpost_ffi)

If you want to start from scratch, you can create a new project with:

```bash

mkdir blogpost_ffi

maturin init # pyo3

```

The default project looks like this:

```rust

use pyo3::prelude::*;

/// Formats the sum of two numbers as string.

#[pyfunction]

fn sum_as_string(a: usize, b: usize) -> PyResult<String> {

Ok((a + b).to_string())

}

/// A Python module implemented in Rust. The name of this function must match

/// the `lib.name` setting in the `Cargo.toml`, else Python will not be able to

/// import the module.

#[pymodule]

fn string_sum(_py: Python<'_>, m: &PyModule) -> PyResult<()> {

m.add_function(wrap_pyfunction!(sum_as_string, m)?)?;

Ok(())

}

```

We can call the function as follows:

```bash

maturin develop

python -c "import blogpost_ffi; print(blogpost_ffi.sum_as_string(1,1))"

# Return: "2"

```

`pyo3` is able to interpret most of the basic Rust type and transform them into Python basic type, so that a Python integer is going to be interpret as a Rust usize without additional work.

However, the automatically interpreted type might not be the most optimized implementation.

### Implementation 1: Default

Let's imagine that, we want to play with arrays, we want to receive an array input and return an array output.

A default inplementation, would look like this:

```rust

#[pyfunction]

fn create_list(a: Vec<&PyAny>) -> PyResult<Vec<&PyAny>> {

// ... Imagine some work here...

Ok(a)

}

#[pymodule]

fn blogpost_ffi(_py: Python, m: &PyModule) -> PyResult<()> {

m.add_function(wrap_pyfunction!(sum_as_string, m)?)?;

m.add_function(wrap_pyfunction!(create_list, m)?)?;

Ok(())

}

```

#### Calling `create_list` for a very large list like: `value = [1] * 100_000_000` is going to return in **2.272s** :tractor:

> Check https://github.com/haixuanTao/blogpost_ffi/blob/main/test_script.py for details on how the function is called.

That's quite slow... The reason being is that this list is going to be interpret one element at a time in a loop. We can do better by trying to use all elements at the same time. And because the data is owned, it's going to be copied once received and once returned.

### Implementation 2: PyBytes

Let's imagine that our list can be represented as a [`PyBytes`](https://docs.python.org/3/library/stdtypes.html?highlight=bytes#bytes) ( so any C-shaped array ). Bytes can be optimized by casting the inputs and output from the Rust side as a `PyBytes`:

```rust

#[pyfunction]

fn create_list_bytes<'a>(py: Python<'a>, a: &'a PyBytes) -> PyResult<&'a PyBytes> {

let s = a.as_bytes();

// ... Imagine some work here...

let output = PyBytes::new_with(py, s.len(), |bytes| {

bytes.copy_from_slice(s);

Ok(())

})?;

Ok(output)

}

```

#### For the same list input, `create_list_bytes` returns in **78 milliseconds**. That's **30x** better :racehorse:

The speedup comes from the possibility to copy the memory range instead of iterating each element and to read without copying.

Now the issue is that:

- `PyBytes` is only available in Python meaning that if we go this route we will have to find optimization for each language.

- `PyBytes` will also probably need to be reconverted into other useful types.

- `PyBytes` needs a copy to be created.

We can try to solve this with [Apache Arrow](arrow.apache.org/).

### Implementation 3: [Apache Arrow](arrow.apache.org/)

Apache Arrow is a universal memory format available in all language. It can represent many different types including `List` and `Struct`.

The same function in `arrow` would look like this:

```rust

#[pyfunction]

fn create_list_arrow(py: Python, a: &PyAny) -> PyResult<Py<PyAny>> {

// ... Imagine some work here...

let arraydata = arrow::array::ArrayData::from_pyarrow(a).unwrap();

let buffer = arraydata.buffers()[0].as_slice();

let len = buffer.len();

// ... Imagine some work here, similar to PyBytes...

// Zero Copy Buffer reference counted

let arc_s = Arc::new(buffer.to_vec());

let ptr = NonNull::new(arc_s.as_ptr() as *mut _).unwrap();

let raw_buffer = unsafe { arrow::buffer::Buffer::from_custom_allocation(ptr, len, arc_s) };

let output = arrow::array::ArrayData::try_new(

arrow::datatypes::DataType::UInt8,

len,

None,

0,

vec![raw_buffer],

vec![],

)

.unwrap();

output.to_pyarrow(py)

}

```

#### Same list, this returns in **33 milliseconds** :racing_motorcycle:. That's **2x** better than `PyBytes`

This is due to having zero copy when sending back the result. The zero-copying is safe because we are reference counting the array and will be deallocating it once all reference has been removed.

The benefits of `arrow` are being able to:

- have zero copy, also meaning that it will scale a lot better with even more elements.

- reuse it in other languages. We only have to replace the last line of the function with the export to the other languages.

- be more extensible than other representation such as `PyBytes`.

- be directly used in `numpy`, `pandas`, and `pytorch` with zero-copy transmutation.

## Debugging

But, dealing with efficient Interface is not the only challenge of bridging multiple languages. You will also have to deal with cross-language debugging.

### `.unwrap()`

Our current implementation uses `.unwrap()`. However, this will panic the whole Python process if there is an error.

Example error:

```bash

thread '<unnamed>' panicked at 'called `Result::unwrap()` on an `Err` value: PyErr { type: <class 'TypeError'>, value: TypeError('Expected instance of pyarrow.lib.Array, got builtins.int'), traceback: None }', src/lib.rs:45:62

note: run with `RUST_BACKTRACE=1` environment variable to display a backtrace

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "/home/peter/Documents/work/blogpost_ffi/test_script.py", line 79, in <module>

array = blogpost_ffi.create_list_arrow(1)

pyo3_runtime.PanicException: called `Result::unwrap()` on an `Err` value: PyErr { type: <class 'TypeError'>, value: TypeError('Expected instance of pyarrow.lib.Array, got builtins.int'), traceback: None }

```

This is also not idiomatic to Python and might surprise users.

### [eyre](https://github.com/eyre-rs/eyre)

Eyre is an easy idiomatic error handling library for Rust applications. You can use eyre by wrapping your `pyo3` project with the `pyo3/eyre` feature flag, to replace all your `.unwrap()` with a `.context("your context")?`. This will transform unrecoverable errors into recoverable Python errors while giving you details about your error.

Same example error as above:

```bash

eyre says: Could not convert arrow data

Caused by:

TypeError: Expected instance of pyarrow.lib.Array, got builtins.int

Location:

src/lib.rs:75:50

```

Although, this is still not super idiomatic Python.

Implementation details:

```rust

#[pyfunction]

fn create_list_arrow_eyre(py: Python, a: &PyAny) -> Result<Py<PyAny>> {

// ... Imagine some work here...

let arraydata =

arrow::array::ArrayData::from_pyarrow(a).context("Could not convert arrow data")?;

let buffer = arraydata.buffers()[0].as_slice();

let len = buffer.len();

// ... Imagine some work here, similar to PyBytes...

// Zero Copy Buffer reference counted

let arc_s = Arc::new(buffer.to_vec());

let ptr = NonNull::new(arc_s.as_ptr() as *mut _).context("Could not create pointer")?;

let raw_buffer = unsafe { arrow::buffer::Buffer::from_custom_allocation(ptr, len, arc_s) };

let output = arrow::array::ArrayData::try_new(

arrow::datatypes::DataType::UInt8,

len,

None,

0,

vec![raw_buffer],

vec![],

)

.context("could not create arrow arraydata")?;

output

.to_pyarrow(py)

.context("Could not convert to pyarrow")

}

```

### Calling Python from Rust, Traceback with `eyre`

However, a good debugging message may not always be automatically generated.

For example, if you're calling Python code from a Rust code, you might lose the error traceback within the Python code.

In this case, you would have to use a custom traceback method of the Python error to have a descriptive error:

```rust

#[pyfunction]

fn call_func_eyre(py: Python, func: Py<PyAny>) -> Result<()> {

// ... Imagine some work here...

let _call_python = func.call0(py).context("function called failed")?;

Ok(())

}

fn traceback(err: pyo3::PyErr) -> eyre::Report {

let traceback = Python::with_gil(|py| err.traceback(py).and_then(|t| t.format().ok()));

if let Some(traceback) = traceback {

eyre::eyre!("{traceback}\n{err}")

} else {

eyre::eyre!("{err}")

}

}

#[pyfunction]

fn call_func_eyre_traceback(py: Python, func: Py<PyAny>) -> Result<()> {

// ... Imagine some work here...

let _call_python = func

.call0(py)

.map_err(traceback) // this will gives you python traceback.

.context("function called failed")?;

Ok(())

}

```

Example errors:

```

---Eyre no traceback---

eyre no traceback says: function called failed

Caused by:

AssertionError: I have no idea what is wrong

Location:

src/lib.rs:89:39

------

```

Better errors:

```

---Eyre traceback---

eyre traceback says: function called failed

Caused by:

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "/home/peter/Documents/work/blogpost_ffi/test_script.py", line 96, in abc

assert False, "I have no idea what is wrong"

AssertionError: I have no idea what is wrong

Location:

src/lib.rs:96:9

------

```

With the traceback, we can quickly identify the root error.

## Memory management

Memory growth and memory leak are common errors when doing FFI.

For example, the current `pyo3` memory model keeps all Python variables until the GIL is released.

Therefore, if you create variables in a `pyfunction` loop, all temporary variables are going to be kept until the GIL is released. This can create high memory usage. This is due to `pyfunction` locking the GIL by default.

Example:

```rust

/// Unbounded memory growth

#[pyfunction]

fn unbounded_memory_growth(py: Python) -> Result<()> {

for _ in 0..10 {

let a: Vec<u8> = vec![0; 40_000_000];

let _ = PyBytes::new(py, &a);

/// Some work happens here.

std::thread::sleep(Duration::from_secs(1));

}

Ok(())

```

#### Calling this function will consume 440MB of memory. :-1:

By understanding the GIL-based memory model, we can use a scoped GIL to have the expected behaviour:

```rust

#[pyfunction]

fn bounded_memory_growth(py: Python) -> Result<()> {

py.allow_threads(|| {

for _ in 0..10 {

Python::with_gil(|py| {

let a: Vec<u8> = vec![0; 40_000_000];

let _bytes = PyBytes::new(py, &a);

/// Some work happens here.

std::thread::sleep(Duration::from_secs(1));

});

}

});

// or

for _ in 0..10 {

let pool = unsafe { py.new_pool() };

let py = pool.python();

let a: Vec<u8> = vec![0; 40_000_000];

let _bytes = PyBytes::new(py, &a);

/// Some work happens here.

std::thread::sleep(Duration::from_secs(1));

}

Ok(())

}

```

#### Calling this function will consume 80MB of memory. :thumbsup:

> [More info can be found here](https://pyo3.rs/main/memory.html#gil-bound-memory)

[Possible fix in Pyo3 0.21!](https://github.com/PyO3/pyo3/issues/3382)

## Race condition

Race condition is also very common within FFI.

One example is when using Python with `pyo3`, you will have to make sure to know exactly when the GIL is locked or unlocked to avoid race conditions. For example, when calling Rust from Python with `pyo3`, you should expect the GIL to be locked when it is a `pyfunction`. This might not be obvious:

```rust

/// Function GIL Lock

#[pyfunction]

fn gil_lock() {

let start_time = Instant::now();

std::thread::spawn(move || {

Python::with_gil(|py| println!("This threaded print was printed after {:#?}", &start_time.elapsed()));

});

std::thread::sleep(Duration::from_secs(10));

}

```

#### This threaded print was printed after 10.0s. :cry:

If we use the GIL in the main function thread or release the GIL at the end of the main function thread, there is no issue.

```rust

/// No gil lock

#[pyfunction]

fn gil_unlock() {

let start_time = Instant::now();

std::thread::spawn(move || {

std::thread::sleep(Duration::from_secs(10));

});

Python::with_gil(|py| println!("1. This was printed after {:#?}", &start_time.elapsed()));

// or

let start_time = Instant::now();

std::thread::spawn(move || {

Python::with_gil(|py| println!("2. This was printed after {:#?}", &start_time.elapsed()));

});

Python::with_gil(|py| {

py.allow_threads(|| {

std::thread::sleep(Duration::from_secs(10));

})

});

}

```

#### "1" was printed after 32µs and "2" was printed after 80µs, so there was no race condition. :smile:

## Tracing

Being able to measure the time spent when interfacing can be very valuable to identify bottlenecks.

But measuring the time spent manually as we did before can be tedious.

What we can do is use a tracing library to do it for us. [Opentelemetry](https://opentelemetry.io/) can help us build a distributed observable system and is capable of bridging multiple languages. [Opentelemetry](https://opentelemetry.io/) can be used for tracing, metrics and logs.

For example, if we had:

```rust

/// No gil lock

#[pyfunction]

fn global_tracing(py: Python, func: Py<PyAny>) {

// global::set_text_map_propagator(opentelemetry_jaeger::Propagator::new());

global::set_text_map_propagator(TraceContextPropagator::new());

// Connect to Jaeger Opentelemetry endpoint

// Start a new endpoint with:

// docker run -d -p6831:6831/udp -p6832:6832/udp -p16686:16686 jaegertracing/all-in-one:latest

let _tracer = opentelemetry_jaeger::new_agent_pipeline()

.with_endpoint("172.17.0.1:6831")

.with_service_name("rust_ffi")

.install_simple()

.unwrap();

let tracer = global::tracer("test");

// Parent Trace, first trace

let _ = tracer.in_span("parent_python_work", |cx| -> Result<()> {

std::thread::sleep(Duration::from_secs(1));

let mut map = HashMap::new();

global::get_text_map_propagator(|propagator| propagator.inject_context(&cx, &mut map));

let output = func

.call1(py, (map,))

.map_err(traceback)

.context("function called failed")?;

let out_map: HashMap<String, String> = output.extract(py).unwrap();

let out_context = global::get_text_map_propagator(|prop| prop.extract(&out_map));

std::thread::sleep(Duration::from_secs(1));

let _span = tracer.start_with_context("after_python_work", &out_context); // third trace

Ok(())

});

}

```

In the Python code, we can also add a tracespan:

```python

def abc(cx):

propagator = TraceContextTextMapPropagator()

context = propagator.extract(carrier=cx)

with tracing.tracer.start_as_current_span(

name="Python_span", context=context

) as child_span:

child_span.add_event("in Python!")

output = {}

tracing.propagator.inject(output)

time.sleep(2)

return output

```

This will give us the following traces:

Using this we can measure the time spent when interfacing languages, identify lock issues, and with the combination of logs and metrics, reduce the complexity of multi-language libraries.

## Distribution

I have mainly focused on creating a Python extension because it's hard to distribute Rust binaries using Python without one. https://github.com/PyO3/pyo3/issues/2901.

If you want something that is easy to use, you will want to use a very idiomatic way of doing so, which for Python is the Python extension route.

# [dora-rs](https://github.com/dora-rs/dora)

Hopefully, this small blog post should be clear enough to help you avoid issues I faced.

The optimization that you see above have all been implemented within my latest project [dora-rs](https://github.com/dora-rs/dora) that lets you build fast and simple dataflows using Rust, Python, C and C++.

We just recently opened a Discord and you can reach me there for literally any question, even just for a quick chat or a coffee: https://discord.gg/ucY3AMeu

I'm also going to present this FFI work at [GOSIM Workshop in Shanghai on the 23rd of Sept 2023](https://workshop2023.gosim.org/schedule#auto)

We're also doing an International Hackathon on Autonomous Driving with a Prize Pool of about 64k Euros for students. For more info on the Hackathon Documentation: https://docs.carsmos.cn/#/en/ and the Official Website for registration: https://competition.atomgit.com/competitionInfo?id=2e1cce10c89711edb4b22fd906d12a1e

This is our first crash test edition, so feel free to reach out on our dedicated Discord channel https://discord.gg/6uKP7xMt if you need any help.

`dora-rs`

Github: https://github.com/dora-rs/dora

Website: https://dora.carsmos.ai/

DIscord: https://discord.gg/XqhQaN8P

----

[Hackathon][Autonomous Driving][AI/ML/Data Science][64k Euros Prize Pool]

For this 2023 rentrée, I'm inviting students from CentraleSupelec to participate in an International Hackathon on Autonomous Driving with a prize pool of about 64k Euros (500k RMB).

For a bit of context, I'm a CentraleSupelec alumni working on a new open source library called dora-rs (https://github.com/dora-rs/dora) that aims at facilitating the development of robotic application.

One such application is autonomous driving, which is at the root of many more specialized applications.

To test out dora-rs, the OpenAtom foundation (https://www.openatom.org/) has granted a prize pool of about 64k Euros for people to try out and use dora-rs in conjunction with Carla (https://carla.org/), a car simulator.

I have reached out to the staff in CentraleSupelec and they agreed in principle to let students work on dora-rs as a student project so that you can work on this hackathon for academic credit during the school year. To learn more or if you have specific questions on academic partnership and project acceptance, please don't hesitate to reach out to me.

Sponsorships for entrepreneurs, clubs, or associations that share common interests in Robotics, AI, or Autonomous Driving are also possible so the time you spend on dora-rs or the Hackathon is also spent on your other activities.

I will try my best to help out during this competition and not leave you in the dark as I deeply believe that the prize can be won by CentraleSupelec.

This is our first crash test edition of this Hackathon, so feel free to contact me on Discord at: https://discord.gg/6uKP7xMt or at tao.xavier@outlook.com for any questions. I can speak French, English and Chinese.

Getting started guide for the Hackathon: https://docs.carsmos.cn/#/en/

Official Website for Hackathon registration: https://competition.atomgit.com/competitionInfo?id=2e1cce10c89711edb4b22fd906d12a1e

dora-rs

Github: https://github.com/dora-rs/dora

Website: https://dora.carsmos.ai/

DIscord: https://discord.gg/XqhQaN8P

Sign in with Wallet

Sign in with Wallet