---

title: COVID-19 Risk Perception

tags: live-v0.1, communication, behaviour

permalink: https://c19vax.scibeh.org/pages/riskperception

---

{%hackmd 5iAEFZ5HRMGXP0SGHjFm-g %}

<!---{%hackmd FnZFg00yRhuCcufU_HBc1w %}--->

{%hackmd GHtBRFZdTV-X1g8ex-NMQg %}

[TOC]

# I am not in danger of COVID-19... or am I?

## Overview

Some people believe that COVID-19 harms only the old or sick, and that healthy, young people are not really in danger of getting sick from it. Although younger people are less at risk than others, this belief is inaccurate and highlights the mismatch between objective risk and subjective risk beliefs. It can also be problematic if it leads to risky behaviors, such as [vaccination freeriding](https://c19vax.scibeh.org/pages/freeriding) or reckless behaviours such as disregarding social distancing and mask wearing ([Siegrist & Bearth, 2021](https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2100411118)). A lower perception of the risks of disease is also associated with lower COVID-19 vaccination intention ([Maftei & Holman, 2021](https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.672634)). To better understand inaccurate risk beliefs, it will help to disentangle the different potential meanings of not being "at risk."

COVID-19 risk has many possible meanings that include:

1. What is the chance that I will **contract** COVID-19?

2. What is the chance that I will **get seriously ill** (e.g., need hospitalization) or **die** from COVID-19?

3. What is the chance that I will suffer from **long-term** side-effects of having COVID-19 ?

## Objective COVID-19 Risk

<span style="color:green">Here, we discuss the various risks to individual from COVID-19, and the individual factors that increase these risks in general. The level of risk for each of these events may also vary depending on the variant of coronavirus that is prevalent at any given time. For example, the Delta variant of the virus had a greater risk of severe illness than some earlier variants ([Tao et al., 2021](https://www.nature.com/articles/s41576-021-00408-x)), while the Omicron variant had a greater risk of contracting the disease ([BMJ, 2021](https://www.bmj.com/content/375/bmj.n3151.full)). You can read more about COVID-19 variants on our [Facts about COVID-19 page](https://c19vax.scibeh.org/pages/covidfacts#What-about-COVID-19-variants)</span>

1. What is the chance that I will **contract** COVID-19?

Research based on data from Japan, Italy and Spain ([Omori et al., 2020](https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-73777-8)) suggests that the chances of someone contracting COVID-19 is not age-dependent, meaning that younger individuals do not seem to be less likely to get coronavirus than older ones. As the researchers say in their paper:

> "the age distributions of COVID-19 mortality show only small variation even though the number of deaths per country shows large variation. (...) Although we cannot fully reject the existence of age-dependency in susceptibility, our results suggest that it does not largely depend on age, but rather that age-dependency in severity highly contributes to the formation of the observed age distribution in mortality."

Similarly, the prevalence of COVID-19 seems to be equal among men and women ([Bassi et al., 2020](https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.142799)).

On the other hand, the prevalence of COVID-19 seems to be higher in neighborhoods with low socio-economic status ([Hatef et al., 2020](https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2020.571808)), indicating that people living in disadvantaged neighborhoods are at higher risk of contracting COVID-19. A multitude of biomedical and social parameters may be responsible for this disparity, revealing structural inequalities ([Tai et al., 2020](https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa815)) that increase the risk of COVID-19 for specific populations.

2. What is the chance that I will **get seriously ill** (e.g., need hospitalization) or **die** from COVID-19?

It is well established ([Ioannidis et al., 2020](https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7327471/); [Parohan et al., 2020](https://doi.org/10.1080/13685538.2020.1774748)) that older individuals are at higher risk of getting seriously ill or dying from COVID-19.

<!--

<sub>_Source: [CDC website](https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/older-adults.html)_</sub>-->

<!-- #REVIEW Stefan Herzog: I can't find the source of this table at https://www.cdc.gov/aging/covid19/covid19-older-adults.html

DAWN: Hm, me neither, it is likely the website updated since this was put in. I would remove the table/image, it is no longer really news that older adults are more likely to die/require hospitalisation. I removed it for now-->

However, this effect seems to be mediated by comorbidities that depend on age, as suggested by a meta-analysis of studies ([Starke et al., 2020](https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17165974)) investigating age effects on mortality from COVID-19.

Belonging to racial or ethnic minorities (which is often highly correlated with low socio-economic status and comorbidities) has also been found to increase the risk of hospitalization or death from COVID-19 ([Aldridge et al., 2020](https://doi.org/10.12688/wellcomeopenres.15922.2); [The Open SAFELY Collaborative, 2020](https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.05.06.20092999); [Kopel et al., 2020](https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2020.00418#h7)). Similarly, being male ([The Open SAFELY Collaborative, 2020](https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.05.06.20092999); [Pérez-López et al., 2020](https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2020.06.017)) is a risk factor for severe disease and death from COVID-19, as is the case with other viral diseases ([Walter & McGregor, 2020](https://dx.doi.org/10.5811%2Fwestjem.2020.4.47536/)). In Italy, early data revealed the age x gender effect on mortality:

_Proportion of deaths in the Italian population by gender and age._

<sub>_Source: [Figure 1 in Bassi et al. (2020)](https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.142799)._</sub>

For women, pregnant women may be at higher risk of death than non-pregnant women of similar characteristics ([Hantoushzadeh et al., 2020](https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2020.04.030)). Finally, people with various comorbidities ([Sanyaolu et al., 2020](https://doi.org/10.1007/s42399-020-00363-4))---primarily cardiovascular disease, hypertension, obesity and cancer ([Noor & Islam, 2020](https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-020-00920-x))---have been found to be at much higher risk of severe effects from COVID-19 than people who were otherwise healthy ([Yang et al., 2020](https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2020.03.017)). Therefore, old age, male gender, pregnancy, comorbidities and belonging to ethnic minorities are risk factors for severe disease and/or death.

<span style="color:green">**However, for everyone, including individuals in these groups, vaccination against COVID-19 is highly effective at reducing the risk of death and severe illness (see e.g., [Watson et al., 2022](https://www.thelancet.com/journals/laninf/article/PIIS1473-3099(22)00320-6/fulltext); [BMJ, 2021](https://www.bmj.com/content/375/bmj.n2582)).**

3. **"Long COVID"**: What is the chance that I will suffer from **long-term** effects of COVID-19?

Even though younger people are at lower risk of getting seriously ill from COVID-19, this does not mean that they are completely safe from it. <span style="color:green">Research is still ongoing to understand long COVID and who is most at risk from it, but it is now apparent people can, and do, suffer long-term effects after infection ([Michelen et al., 2021](https://gh.bmj.com/content/6/9/e005427)).

Thus far, long COVID appears to cover a multitude of neuro-cognitive complications (fatigue, myopathy, loss of smell, change of taste, confusion, headaches, dizziness, ataxia, seizure, depressed level of consciousness and even stroke: [Iadecola et al., 2020](https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2020.08.028); [Pleasure et al., 2020](https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.1065); [Aghagoli et al., 2020](https://doi.org/10.1007/s12028-020-01049-4)). Some of these effects may be deadly, as in the case of stroke that seems to be a serious complication in cases of young patients ([Oxley et al., 2020](https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMc2009787); [Fifi & Mocco, 2020](https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(20)30272-6)). Other symptoms may persist long after the disease is typically over ([Miyazato et al., 2020](https://doi.org/10.1093/ofid/ofaa507); [Baker et al., 2020](https://bjanaesthesia.org/action/showPdf?pii=S0007-0912%2820%2930849-7); [Davis et al., 2021](https://www.thelancet.com/journals/eclinm/article/PIIS2589-5370(21)00299-6/fulltext); [Huang et al., 2021](https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(20)32656-8/fulltext); [Ayoubkhani et al., 2021](https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n693)).

These effects are more common in cases of severe disease but they also appear in milder ones. In the UK, the prevalence of such "long COVID" symptoms lasting for at least 12 weeks was estimated at 13.7%, with higher prevalence for females (14.7%) than males (12.7%), and the highest prevalence among 25-34 year olds (18.2%). Among children, one large study put the prevalence of long COVID at 14%).Therefore, while younger adults may be less vulnerable to dying from COVID-19 infection, they still risk suffering effects over the long term, and we still do not know the full picture of what the neurocognitive effects are over the long term.

In conclusion, COVID-19 seems to be equally prevalent across age and gender, but more likely to spread in disadvantaged neighborhoods. The risk of severe effects and death is higher for old age, male gender, existing comorbidities, and most racial and ethnic minorities. Besides the complications of the lung system, COVID-19 often has neurocognitive adverse effects that may persist for a prolonged period. Even individuals not in high-risk groups can get COVID-19, and indeed long COVID. Finally, people at low risk of getting seriously ill from COVID-19 can still be asymptomatic carriers of the virus, thus endangering the health of their families and friends, some of whom will belong to a high-risk group.

still get COVID-19 and need to take the necessary precautions (face masks, hygiene habits, social distancing) as well as vaccinate themselves when possible.

Therefore, it remains advisable be vaccinated to reduce the risk of severe symptoms from COVID-19, and also to think about whether there are appropriate precautions you could take (face masks, hygiene habits, social distancing) to protect you and your loved ones from getting sick from COVID-19.

:::info

_The Economist_ provides an **[interactive digital tool ](https://www.economist.com/graphic-detail/covid-pandemic-mortality-risk-estimator)** to visualise the risks of suffering adverse consequences if one contracts COVID-19.

:::

## Subjective Beliefs about COVID-19 Risk

Risk perception is **subjective** and often does not align with **objective** risk estimates. For example, an estimated third of US adults do not believe they are in a category at risk for seasonal infuenza and as a result do not get vaccinated ([Brewer & Hallman, 2006](https://doi.org/10.1086/508466)).<!-- #REVIEW: Stefan Herzog: I'm not sure that the statement in the preceeding sentence is correct or understandable. The paper says "One-third of respondents (98 of 300) incorrectly perceived themselves to be at low risk despite actually being at high risk." In the abstract it says "One-half of individuals at high risk of influenza did not know that they were at high risk and, therefore, were not vaccinated." which is, I think, the statistic we should refer to. --> Furthermore, risk perceptions are often an instinctive and intuitive reaction, affected by feelings (e.g., [Slovic et al., 2004](https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0272-4332.2004.00433.x), listen also to: [Fischhoff, 2020](https://www.apa.org/research/action/speaking-of-psychology/coronavirus-anxiety)). When it comes to COVID-19, subjective perceptions about the risk of contagion may also be conflated with social risk perception, where people perceive those they trust to be less risky, and [thus take fewer protective behaviours around them as opposed to around strangers](https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-10925-3/).

Specific characteristics of hazards can increase or reduce risk perception. For example, **seasonal influenza** elicits relatively low perceived risk as people are familiar with the flu, they have experienced it directly or indirectly, it is common, and they may believe it is not deadly. In contrast, COVID-19 is likely to induce higher perceived risk, especially in the early phases of the pandemic, as it is a new and deadly disease, for which both science and people initially had limited information and experience. It thus evokes strong feelings. Sometimes this difference has been exploited by saying that "COVID-19 is just like the seasonal flu" to reduce perceptions of the threat it poses.

COVID-19 risk perception is associated with reported **protective behaviours** (the higher the level of risk perceived, the more people performe protective behaviours, e.g., [Dryhurst et al., 2020](https://doi.org/10.1080/13669877.2020.1758193); [Ning et al., 2020](https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09892-y); [Rubaltelli et al., 2020](https://doi.org/10.1111/bjhp.12473)) and with **vaccine acceptance** (the more people are worried or perceive COVID-19 to be risky, the more likely they are to accept a vaccine, e.g., [Kerr et al., 2021](https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-048025), [Schwarzinger et al., 2021](https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(21)00012-8); but see also [Karlsson et al., 2021](https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2020.110590)).

A problematic issue regarding COVID-19 risk perception is the difference in attitudes across gender. Even though men are more likley to die from COVID-19, they are likely to worry about it ([Galasso et al., 2020](https://www.pnas.org/content/117/44/27285.short?casa_token=Upcx6z36jCkAAAAA:Ij-nkiAURHOe5OLKgN8IAYFroRCDRHODU6deiSHa-IDEvXvYGFwDiPkUp7rdL8F3oVaOuwQUJ-XqArU)) and they conform less to social distancing and hygiene rules than women. (No data are available on these behaviors for trans people.)

## Risk Appraisals and Vaccination

Risk appraisals are reliably associated with vaccine uptake across multiple studies ([Brewer et al., 2007](https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17385964/)). The term risk appraisal includes **cognitive** constructs such as perceived likelihoood or severity, **affective** constructs such as worry and fear, and constructs that combine the two such as anticipated regret ([Kiviniemi et al., 2017](https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/08870446.2017.1324973)). Of these risk appraisals, the largest correlate of health behaviors is anticipated regret: expecting to wish that one had made a different choice ([Brewer et al. 2016](https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27607136/)). Other risk appraisals associated with health behavior include worry, fear, perceived likelihood (the chances the harm will happen) and perceived severity (the amount of harm). Recent studies find that higher perceived risk and worry about COVID-19 are associated with being more interested in getting the COVID-19 vaccine.

Campaigns to promote uptake of COVID-19 vaccines may try to increase perceived risk of the disease, but this is unlikely to be effective. A meta-analysis of 16 intervention studies by [Parsons and colleagues (2018)](https://bpspsychub.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/bjhp.12340) shows that such interventions can increase perceived risk, but they do not increase uptake. More generally, interventions to change what people think and feel are not the best way to change vaccine uptake ([Brewer et al., 2017](https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29611455/)). Interventions that build on existing good intentions are the most reliably effective in boosting vaccine uptake. That said, many communications must adress risk, and they should do so in a way that is well understood and does not lead to misunderstandings. Widespread agreement that COVID-19 is a serious threat can support the programs and policies that effectively boost vaccine uptake ([Brewer et al., 2017](https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29611455/)).

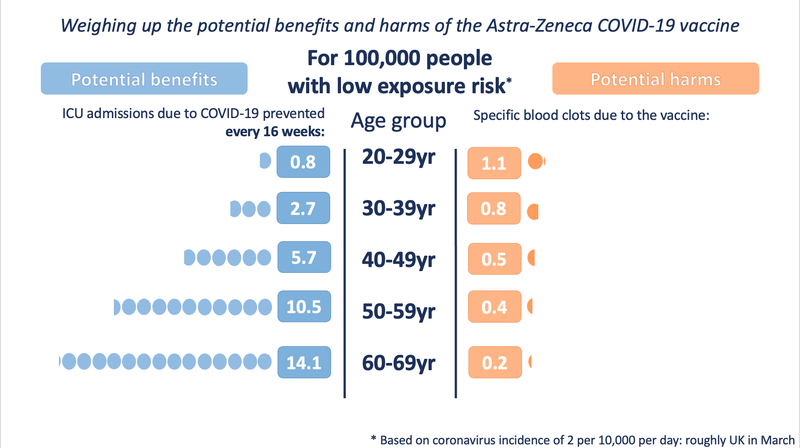

## Weighing up the risks of COVID against side effects risks

As with all other medical treatments, vaccinations for COVID-19 are not without risk of [side effects](https://c19vax.scibeh.org/pages/sideeffects) as well. We should always weigh up the different risks when making an informed decision. Science communicators and medical professionals also need to [communicate these risks transparently](https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-021-01257-8)---but put them into context.

In the case of COVID-19, we need to consider the risk of experiencing side effects from treatment against the risk of catching COVID-19 and experiencing severe symptoms (or long COVID) from it. To give some examples, we look here at some of the adverse side effects risks that have been discussed in relation to the COVID-19 vaccines.

This chart, taken from the [Winton Centre for Risk and Evidence Communication](https://wintoncentre.maths.cam.ac.uk/news/communicating-potential-benefits-and-harms-astra-zeneca-covid-19-vaccine/), visualises the comparative risks associated with COVID-19 vs. the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine for a given prevalence of the virus in the community (other different risk scenario charts can be found on their website).

<sub>_Source: [Winton Centre for Risk and Evidence Communication](https://wintoncentre.maths.cam.ac.uk/news/communicating-potential-benefits-and-harms-astra-zeneca-covid-19-vaccine/)_</sub>

Similarly, the reported risks of myocarditis (heart muscle inflammation) among younger vaccine recipients sound frightening, but experiencing this post-vaccination is both rare (low probability) and cases are typically mild, treatable with anti-inflammatory medicine, and resolved within a few weeks (low severity) ([Vogel & Couzin-Frankel, 2021](https://www.science.org/news/2021/06/israel-reports-link-between-rare-cases-heart-inflammation-and-covid-19-vaccination)).

In comparison, previously healthy people who catch COVID-19 also have an [increased risk of myocarditis](https://www.science.org/news/2020/09/evidence-builds-covid-19-can-damage-heart-doctors-are-racing-understand-it?_ga=2.234584606.1619046891.1631717828-1514382933.1631717828) ([Puntmann et al., 2020](https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamacardiology/fullarticle/2768916)). One preprint estimates this risk of myocarditis from COVID-19 to be 450 per million in young men (compared to 76.5 per million post vaccine): a risk that is nearly 6 times higher from COVID-19 than from the vaccine ([Singer et al., 2021](https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.07.23.21260998v1.full.pdf)).

This assessment by the CDC weighs the risks of myocarditis for each age grounp and gender against the benefits of vaccination:

<sub>***Individual-level estimated COVID-19 cases and COVID-19-associated hospitalizations, intensive care unit admissions, and deaths prevented after use of 2-dose mRNA COVID-19 vaccine for 120 days and number of myocarditis cases expected per million second mRNA vaccine doses administered, by sex and age group*---United States, 2021**</sub>

<sub>_Source: [Gargano et al., 2021](https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/70/wr/pdfs/mm7027e2-H.pdf)_</sub>

<sub>**Abbreviations:** ICU = intensive care unit </sub>

<sub>* This analysis evaluated direct benefits and harms, per million second doses of mRNA COVID-19 vaccine given in each age group, over 120 days. The number of events per million persons aged 12-29 years are the averages of numbers per million persons aged 12-17 years, 18-24 years, and 25-29 years.</sub>

<sub>† Receipt of 2 doses of mRNA COVID-19 vaccine, compared with no vaccination.</sub>

<sub>§ Case numbers have been rounded to the nearest hundred.</sub>

<sub>¶ Ranges calculated as ±10% of crude Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System reporting rates. Estimates include cases of myocarditis, pericarditis, and myopericarditis.</sub>

<br>

Overall, [Barda et al. (2021)](https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa2110475) compared the occurrence of the same adverse events after vaccination and after COVID-19 infection among patients in Israel. The risk of most of the adverse events was substantially increased after COVID infection, as opposed to vaccination:

<sub>_Source: [Barda et al. (2021)](https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa2110475)_</sub>

<sub>Note: "Risk difference" refers to the difference in risk of the adverse event between an exposed group and an unexposed group ([Kim, 2017](https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5300861/)).</sub>

It is also worth considering that catching COVID-19 poses a risk of severe disease not just to oneself, but others as well, while benefits of vaccination are for individuals as well as those around them.</span>

## How much does vaccination reduce the risks associated with COVID-19?

The COVID-19 vaccines are highly effective at reducing transmission and preventing severe symptoms from the disease. However, vaccines are not perfect. Efficacy rates are not 100%, meaning that there is still the possibility of infection after being vaccinated---particularly with new variants of the disease---especially if one ceases to take precautions. Behavioural surveys [suggest that people may adhere less to regulations once they become vaccinated](https://www.theguardian.com/society/2021/feb/27/people-less-likely-adhere-covid-rules-after-vaccination).

<!-----and possibly before they have received a second vaccine dose (and thereby the best protection available). -->

How much the vaccines are able to reduce transmission (i.e., reduce the risk of catching and/or spreading the virus) is uncertain, as this is difficult to measure, especially because people may be asymptomatic, and the virus is constantly mutating to develop new variants of the disease that may be able to re-infect indivduals.

Nonetheless, data indicate that the vaccines have greatly reduced the risk of **severe symptoms**. Hospitalisation rates from COVID-19 have been increasing among unvaccinated people in their 20s and 30s---for example, in mid-2021, this group made up over 20% of hospitalisations in England (vs. 5.4% in January 2021 at the start of the vaccination campaign) ([Iacobucci, 2021](https://www.bmj.com/content/374/bmj.n1963)). One study in the UK, conducted when the Delta variant of the disease was prevalent, found that only unvaccinated patients had a significantly higher risk of hospitalisation with the Delta (vs. Alpha) variant ([Twohig et al., 2021](https://www.thelancet.com/journals/laninf/article/PIIS1473-3099(21)00475-8/fulltext)).

<span style="color:green">There is also evidence that vaccination may reduce the risk of long COVID, though only slightly ([by about 15%, based on a study of over 13 million people](https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-022-01453-0); [Al-Aly et al., 2022](https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-022-01840-0 ).

This suggests that as the virus mutates and new variants emerge, even if vaccines do not eliminate the risk of catching the virus, they are still the best way to reduce your risk of suffering severely from the disease.

## Facts against some common myths regarding COVID-19 Risks

### FACT: Young and healthy people can die or suffer severe consequences

_MYTH: "Only old people or people with comorbidities die or get severely ill from COVID-19."_

It is true that old people and people with comorbidities are affected the most, but young and healthy people can also die or suffer severe consequences. Indeed, there is some evidence that COVID-19 might leave even asymptomatic patients with consequences such as lung scars, and it is not yet known how this might affect their health in the long term. Low risk does not equate to certainty of no risk.

### FACT: A person cannot fully control or eliminate the risks from COVID-19

_MYTH: "I am always careful and I respect the recommendations, therefore I am not at risk."_

The behaviour of others is also an important contributor to your risk from COVID-19. For example, if you are in a closed space and nobody around you wears a mask properly, your risk of getting infected is higher than when everybody wear a mask properly.

### FACT: The risks from COVID-19 depend on how everyone is behaving over time, not just one individual.

_MYTH: "If I haven't caught it until now, if I don't change my behaviour, why would I be at higher risk now?"_

The risk of contracting COVID-19 is not exclusively dependent on the behaviour of individuals. It is important to consider how the case rates may have changed around you. The more people who have COVID-19 around you, the more likely you are to get it. If nobody in your community has COVID-19, you are not going to have it regardless of your behaviour. If most people around you have it, you have a higher risk of contracting COVID-19, even if you follow all protective recommendations (e.g., healthcare professionals caring for COVID-19 patients are at higher risk of contracting it). Also, there is a time lag between when people are infectious and when they know they are infected. As such, you could think that your community is safe while this is not the case. This is how many outbreaks happen, esecially within the family context.

### FACT: COVID-19 has a case fatality rate that is 21 times higher than that of seasonal flu

_MYTH: "COVID is just like a bad flu."_

The case fatality rate---how many people with symptoms die of the disease---for COVID-19 is [about 2%, compared to 0.1% for seasonal flu](https://www.newstatesman.com/science-tech/coronavirus/2021/01/eight-biggest-covid-sceptic-myths-and-why-they-re-wrong). COVID-19 is also much more infectious than the flu and will infect more people with a much-deadlier virus. It has already caused many more hospitalisations than the worst flu seasons, even with social distancing measures in place.

<br>

:::success

**[Anti-Virus: The Covid-19 FAQ](https://www.covidfaq.co/) provides more debunkings of COVID-19 myths.**

We also have a dedicated page on **[debunking COVID-19 vaccination myths](https://c19vax.scibeh.org/pages/misinfo_myths).**

:::

<br>

:::warning

Learn more about [how **behavioural measures control COVID-19**](https://c19vax.scibeh.org/pages/c19behaviour).

Learn more [**facts about COVID-19**](https://c19vax.scibeh.org/pages/covidfacts) and [**facts about COVID-19 vaccines**](https://c19vax.scibeh.org/pages/c19vaxfacts).

:::

----

<sub>Page contributors: Teresa Gavaruzzi, Konstantinos Armaos, Stephan Lewandowsky, Dawn Holford, Stefan Herzog, Noel T. Brewer </sub>

{%hackmd GHtBRFZdTV-X1g8ex-NMQg %}

{%hackmd TLvrFXK3QuCTATgnMJ2rng %}

{%hackmd oTcI4lFnS12N2biKAaBP6w %}