# OpenMP

## Getting started with OpenMP

### 2.1 Welcome to Week 2

OpenMP is a shared memory threaded programming model that can be used to incrementally upgrade existing code for parallel execution. Upgraded code can still be compiled serially. This is a great feature of OpenMP that gives you opportunity to check if parallel execution provides the same results as a serial version. To understand the automatic parallelisation better we will initially take a look into runtime functions. They are usually not needed in simple OpenMP programs. Some basic compiler or pragma directives and scope of variables will be introduced to understand the logic of threaded access to the memory.

Work sharing directives and synchronisation of threads will be discussed within few examples. How to collect results from threads will be shown with common reduction clauses. At the end of this week we will present interesting task based parallelism approach. Don’t forget to experiment with exercises because those are your main learning opportunity. Let's dive in.

The structure of this week was inspired by HLRS OpenMP courses (courtesy: Rolf Rabenseifner (HLRS)).

### 2.2 Runtime functions

The purpose of runtime functions is the management or modification of the parallel processes that we want to use in our code. They come with the OpenMP library.

For C++ and C, you can add the

~~~c

#include <omp.h>

~~~

header file to your code in the beginning of the file and then this library includes all the standard runtime functions that you need and you want to use. The functions that we will be using in our tutorial today can be accessed from the link in the transcript or in the resources.

* To set the desired number of threads, use

~~~c

omp_set_num_threads(n)

~~~

For example, if you want to *parallelise* your program with, let's say, 12 threads, you specify the number of threads in the program using the function

~~~c

omp_set_num_threads(12)

~~~

With this the program will only work with 12 threads.

* To return the current number of threads, use

~~~c

omp_get_num_threads()

~~~

With this we set a number of threads and we will return the current number of threads. So, like our previous example, if you specify the number of threads to 12 then calling this function will return the number of threads that are being used in the program.

* To return the ID of this thread, use

~~~c

omp_get_thread_num()

~~~

So, calling this function, when you are in a specific thread, would return an integer that is unique for every thread that is used in the code to *parallelise* your task.

* To return `true` if inside parallel region, use

~~~c

omp_in_parallel()

~~~

This function returns `true` if it is specified inside a parallel region. If it is not, i.e., if it is specified in serial region, it will return `false`. And again, if you want to use these functions, you need to specify the appropriate header file at the beginning of your C code. Of course, there are multiple other runtime functions that are available in OpenMP.

#### Example

Let's observe the following example.

~~~ c

#include <stdio.h>

#include <omp.h>

int main()

{

int num_threads = 4;

omp_set_num_threads(num_threads);

int rank;

#pragma omp parallel

{

rank = omp_get_thread_num();

int nr_threads = omp_get_num_threads();

printf("I am thread %i of %i threads\n",

rank,

nr_threads);

}

}

~~~

Take a moment and try to understand what is happening in the code above.

* What is the expected output? What are the values of `rank` and `nr_threads`?

* Is the output always the same? What order are the threads printing in?

* What would happen if we change the number of threads to 12?

Now go to the exercise, try it out and check if your answers were correct.

[](https://mybinder.org/v2/gh/kosl/ihipp-examples/HEAD?filepath=OpenMP/Runtime-functions.ipynb)

[](https://colab.research.google.com/drive/158oODa_ZJFLhynei0jZBQkxPNUcbLlaN)

### 2.3 Variables and constructs

#### Environment Variables

The next thing that we have to take a look at are environment variables. Contrary to runtime functions, environment variables are not used in the code but are specified in the environment, where you are compiling and running your code. The purpose of environment variables is to control the execution of parallel program at runtime. As these are not specified in the code, you could specify them for example in a Linux terminal before you compile and run your program. Let's go through the three most common environment variables.

To specify the number of threads to use

~~~sh

export OMP_NUM_THREADS=4

~~~

With this you can set the environment variable. For example, if you're using the bash terminal you can export this variable and specify a fixed number of threads and the program will only work with this specified number of threads. The same goes if you are using other terminals. For example, in TCSH, the usage of the environment variable is achieved through using the key word `setenv` and you can specify the number of threads to be used in a similar way

~~~csh

setenv OMP_NUM_THREADS n

~~~

To specify on which CPUs the threads should be placed, use

~~~sh

OMP_PLACES

~~~

To show OpenMP version and environment, use

~~~sh

OMP_DISPLAY_ENV

~~~

This basically shows the OpenMP version that you are in.

Of course, there are multiple other environmental variables that you can use.

For GCC compiler you can check the link and check the environment variables that you want to use yourself along with all the explanation and examples on how to use those environment variables.

#### Parallel constructs

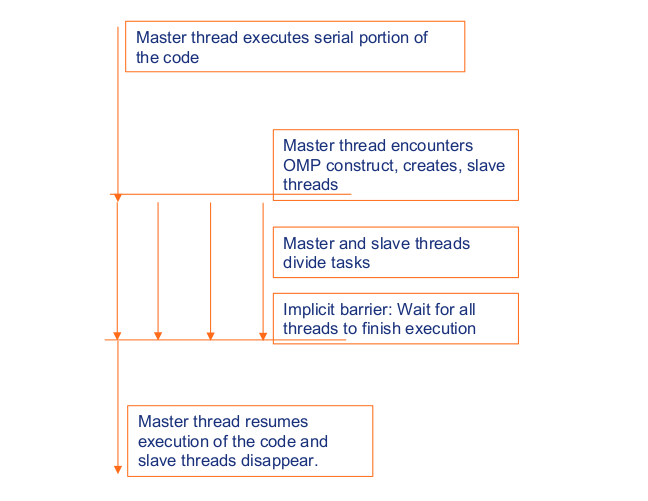

Parallel construct is the basic or the fundamental construct when using OpenMP. So, every thread basically executes the same statements which are inside the *parallel region* simultaneously, as you can see on this image.

**Image courtesy: Rolf Rabenseifner (HLRS)**

So, first we have a master thread that executes the serial portion of the code. Then we come to a `pragma omp` statement. We can see here that the master first encounters this `omp` construct and creates multiple threads, what we call *slave threads* that run in parallel. Subsequently the master and slave threads divide the tasks between each other. In the end, we specify an implicit barrier, so when this barrier is reached, the threads finish and we wait for all threads to finish the execution. Following this, when all the threads have finished the execution, we go back to the master thread that finally resumes the execution of the code. In this step, of course, the slave threads are gone because they have completed their task.

In C this implicit barrier is specified with

~~~c

#pragma omp parallel

{

...

}

~~~

Let's observe the following code.

~~~ c

#include <omp.h>

#include <stdio.h>

int main ()

{

int num_threads = 4;

omp_set_num_threads(num_threads);

int rank;

#pragma omp parallel

{

rank = omp_get_thread_num();

int nr_threads = omp_get_num_threads();

printf("I am thread %i of %i threads\n",

rank,

nr_threads);

}

}

~~~

Take a moment and try to understand what is happening in the code

above. Note the usage of the construct and runtime functions defined earlier in the article.

[](https://mybinder.org/v2/gh/kosl/ihipp-examples/HEAD?filepath=OpenMP/Runtime-functions.ipynb)

[](https://colab.research.google.com/drive/158oODa_ZJFLhynei0jZBQkxPNUcbLlaN)

### 2.4 Clauses and directive format

#### Directive format

So far we have just specified a parallel region and the code was executed in serial. Now we will move ahead to see directives for the OpenMP. The format for using a directive is as follows

~~~c

#pragma omp directive_name [clause[clause]...]

~~~

We have already seen and used `pragma omp parallel` that was a directive to execute the region in parallel. In this format we also have *clauses* in order to specify different parameters. For example, a `private` variable is a variable that is private to each thread whereas a `shared` variable is one that is shared for all threads and any thread can access and modify it.

We will explore the clauses more in the following subsection. For now we will learn about the *conditionals*. Similar to any programming language OpenMP also has

conditional statements. So for example, we can also specify an `if`

statement in OpenMP in the following way

~~~c

#ifdef _OPENMP

//block of code to be executed if code was compiled with OpenMP, for example

printf("Number of threads: %d", omp_get_num_threads);

#else

//block of code to be executed if code was compiled without OpenMP

#endif

~~~

When we specify `#ifdef _OPENMP` then the code will execute and when it comes to this `if` statement, it will track whether the code is compiled with OpenMP. In this case if it was compiled with OpenMP with the flag `#ifdef _OPENMP`, then it will enter the subsequent block of code to execute it. Otherwise, if the code was compiled *serially*, the block of code following the `else` statement would be executed . And of course we close the conditional statements with `endif`.

The following example illustrates the use of conditional compilation. With OpenMP compilation, the `_OPENMP` becomes defined.

~~~c

#include <stdio.h>

#include <omp.h>

int main ()

{

int rank;

#ifdef _OPENMP

#pragma omp parallel num_threads(4) private(rank)

{

rank = omp_get_thread_num();

int nr_threads = omp_get_num_threads();

printf("I am thread %i of %i threads\n",

rank,

nr_threads);

}

#else

{

printf("This program is not compiled with OpenMP\n");

}

#endif

}

~~~

> > $ gcc example.c

> > This program is not compiled with OpenMP

> >

> > $ gcc -fopenmp example.c

> > I am thread 3 of 4 threads

> > I am thread 2 of 4 threads

> > I am thread 1 of 4 threads

> > I am thread 0 of 4 threads

[](https://mybinder.org/v2/gh/kosl/ihipp-examples/HEAD?filepath=OpenMP/Conditionals.ipynb)

[](https://colab.research.google.com/drive/16bmVcGqPCfqTgFdAMVsiPkiwKqilLAam)

#### Clauses

The directive format we just have learnt

~~~c

#pragma omp directive_name [clause[clause]...]

~~~

is an important keyword with OpenMP that we put in the beginning of our code on the line where we want the *parallel* region to start and then we mention the *directive name* and the *clause*. In this subsection we will learn about *clauses*.

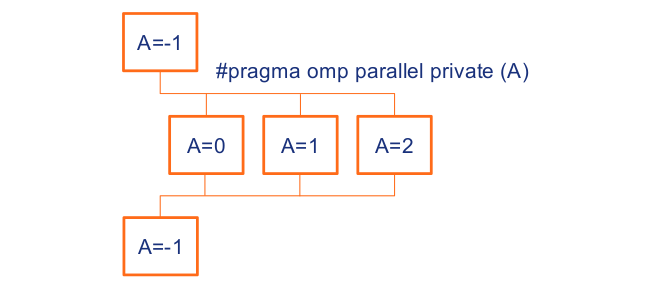

There are basically two kind of clauses, i.e., private or shared. A private variable would be a variable that is private to each thread.

**Image courtesy: Rolf Rabenseifner (HLRS)**

So, we execute, e.g.

~~~c

int A;

#pragma omp parallel private(A)

{

A = omp_get_thread_num();

...

}

~~~

Here we define an integer `A` in C code. Then we define the OpenMP directive, i.e., the `omp parallel` and the `private A`. So, what happens here is that any time we will get a new thread, this variable `A` will be assigned inside of each thread individually. This would imply that the value of `A` will go to the number of threads. So, in the first thread it will be `0`, in the second thread the value of this variable will be `1` because this would be the `ID` of the thread and in the third the value will be `2`, and so on. We can see clearly that these variables are basically private, meaning that they are existing inside each thread. This implies that the variable `A` (0) in the first thread cannot be accessed by the variable `A` (1) in the second thread. So, this infers that this variable is basically private to each individual thread in our program. And of course the opposite of this is the shared variable. If we specify that a variable is a shared variable this would signify that the variable will be shared between the threads. If we specify the variable outside of the parallel region, so right before the

~~~c

#pragma omp parallel

~~~

this variable will be accessed by every thread. To exemplify, let's say if we have a `for` loop and we add a number to it in every iteration, we can just specify it to be a shared variable. In this case, whenever any thread will update the shared variable, it will add numbers to it. This is an adequate way to use the `for` loop that we will see soon in the following subsections.

So, to sum up, the distinction between private and shared: the private variable is available only to one thread and cannot be accessed by any other thread whereas a shared variable cannot only be accessed by every thread in the part of the program but it can also be updated by each thread simultaneously.

Let's have a look at the code below.

~~~c

#include <stdio.h>

#include <omp.h>

int main ()

{

int num_threads = 4;

omp_set_num_threads(num_threads);

int private_var = 1000;

int shared_var = 5000;

int rank;

#pragma omp parallel private(private_var, rank) shared(shared_var)

{

rank = omp_get_thread_num();

printf("Thread ID is: %d\n", rank);

private_var = private_var + num_threads;

printf("Value of private_var is: %d\n", private_var);

shared_var = shared_var + num_threads;

printf("Value of shared_var is: %d\n", shared_var);

}

}

~~~

Run the code above and observe the output. How does the value of private and shared variable changes when accessed by different threads? Does the value of shared variable increase when being modified by multiple threads? Why?

There might also be a race condition here. The write and immediate read of the variable inside the parallel region is a write-read race condition. Two or more threads access the same shared variable and modify it and these accesses are unsynchronized. We will see a more clear example of a race condition in *Parallel region* exercise.

[](https://mybinder.org/v2/gh/kosl/ihipp-examples/HEAD?filepath=OpenMP/Clauses.ipynb)

[](https://colab.research.google.com/drive/1s-lhP8bCBmZW1UDyN76Zuu8jAK4NRyxk)

### 2.5 Clauses

Let's observe the following example

~~~c

#include <stdio.h>

#include <omp.h>

int main()

{

int num_threads = 4;

omp_set_num_threads(num_threads);

int private_var = 1000;

int shared_var = 5000;

int rank;

#pragma omp parallel private(private_var) shared(shared_var)

{

rank = omp_get_thread_num();

printf("Thread ID is: %d\n", rank);

private_var = private_var + num_threads;

printf("Value of private_var is: %d\n", private_var);

shared_var = shared_var + num_threads;

printf("Value of shared_var is: %d\n", shared_var);

}

}

~~~

Take a moment and try to understand what is happening in the code above.

* How does the value of private and shared variable change when accessed by different threads?

* Does the value of shared variable increase when being modified by multiple threads? Why?

* Does the value of private variable increase when being modified by multiple threads?

Now go to the exercise, try it out and check if your answers were correct.

[](https://mybinder.org/v2/gh/kosl/ihipp-examples/HEAD?filepath=OpenMP/Clauses.ipynb)

[](https://colab.research.google.com/drive/1s-lhP8bCBmZW1UDyN76Zuu8jAK4NRyxk)

### 2.6 Parallel region

In this exercise you will get to practice using basic runtime functions, directive format, parallel constructs and clauses which we have learned so far.

The code for this exercise is under the following instructions in a Jupyter notebook. You will start from this provided *Hello world* template. What is the expected output?

~~~c

#include <stdio.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <omp.h>

int main()

{

int i;

i = -1;

printf("hello world %d\n", i );

}

~~~

#### Exercise

1. Go to the exercise and set the desired number of threads to 4 using one of the runtime functions.

2. Set variable `i` to ID of this thread using one of the runtime functions.

3. Add a parallel region to make the code run in parallel.

4. Add the OpenMP conditional clause when including OpenMP header file and using runtime functions.

Before you run the program, what do you think will happen?

Now, run the program and observe the output. You can change the number of threads to 12 or other and observe the output.

5. Add a private clause to the parallel region for the variable `i`.

What will happen? Observe the difference in the output. Why is the output different? Check if you get a race condition.

Race condition:

* Two threads access the same shared variable and at least one thread modifies the variable and accesses are not synchonized.

* The outcome of the program depends on timing of the threads in the team.

* This is caused by unintended shared of data.

Don't worry if you always get a correct output, because a compiler may use a private register on each thread instead of writing directly into memory.

#### Expected output:

* If compiled with OpenMP, the program should output »hello world« and the ID of each thread.

[](https://mybinder.org/v2/gh/kosl/ihipp-examples/HEAD?filepath=OpenMP/Exercise-Parallel-region.ipynb)

[](https://colab.research.google.com/drive/1IePNYHd7q_BYSsR-1qnoBHBzOTjYSx7q)

### 2.7 Quiz on OpenMP basics

We just covered the basics of OpenMP, runtime functions, constructs and directive format. This quiz tests your knowledge of OpenMP basics.

1. Directives appear just before a block of code, which is delimited by:

( ) ( … )

( ) [ … ]

(x) { … }

( ) < … >

2. Which of these is a correct way for an OpenMP program to set the number of available threads to 4?

( ) At the beginning of an OpenMP program, use the library function omp_get_num_threads(4) to set the number of threads to 4.

( ) At the beginning of an OpenMP program, use the library function num_threads(4) to set the number of threads to 4.

(x) In bash, export OMP_NUM_THREADS=4.

( ) At the beginning of an OpenMP program, use the library function omp_num_threads(4) to set the number of threads to 4.

3. Variables defined in the shared clause are shared among all threads.

(x) True

( ) False

4. When compiling an OpenMP program with gcc, what flag must be included?

(x) -fopenmp

( ) -o hello

( ) ./openmp

( ) None of the answers

5. Code in an OpenMP program that is not covered by a pragma is executed by how many threads?

(x) Single thread

( ) Two threads

( ) All threads

6. If a variable is defined in the private clause within a construct, a separate copy of the same variable is created for every thread.

(x) True

( ) False

7. How many iterations are executed if 4 threads execute the below program?

~~~c

#pragma omp parallel private(i)

{

#pragma omp for

for (int i = 0; i < 100; i++)

{

a[i] = i;

}

}

~~~

( ) 20

( ) 40

(x) 25

( ) 35

### 2.8 Which thread executes which statement or operation?

In the following steps we learn how to really organize our work in parallel. Please, share your ideas on how we can achieve that.

Do you know of possible ways of organizing work in parallel? How can the operations be distributed between threads? Is there a way to control the order of threads?

### 2.9 OpenMP constructs

#### Worksharing constructs

The work-sharing constructs divide the execution of the code region among different members of team threads. These are the constructs that do not launch the new threads and they are enclosed dynamically within the parallel region.

Some examples of the work sharing constructs are:

- sections

- for

- task

- single

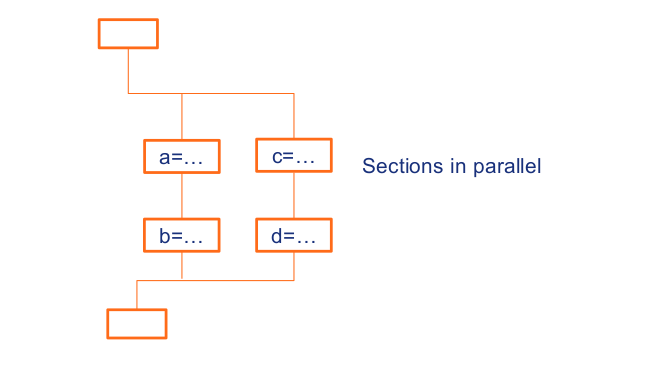

**Section construct**

We will first see a code example for using the sections construct where we can specify it through directive *sections*.

~~~c

#pragma omp parallel

{

#pragma omp sections

{{a=...; b=...;}

#pragma omp section

{

c=...; d=...;

}

}// end of sections

}// end of parallel

~~~

When we use *sections* construct, multiple blocks of code are executed in parallel. When we specify section and we put a task into it, this specific task will execute in one thread. And then when we go on to another section, it will execute its task in a different thread. This way we can add these sections inside our `pragma omp parallel` code by specifying a section per each thread that will be executed in that each individual thread.

**Image courtesy: Rolf Rabenseifner (HLRS)**

In the example code above we can see that inside the section we have specified variables `a` and `b`. When this code is executed, a new thread is generated with these variables and the same follows for the variables `c` and `d` which are specified in a different section and hence are in a different thread.

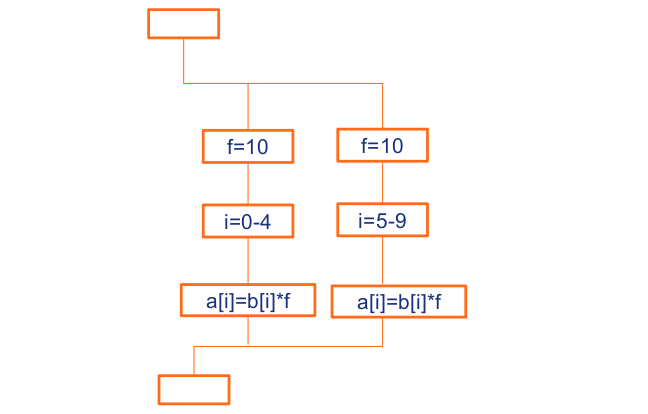

**For construct**

In computer science, for-loop is a control flow statement which specifies iteration. This allows code to be executed repeatedly. Such tasks, similar in action and executed multiple times, can be parallelised as well. In OpenMP, we can use the `for` construct in

`#pragma omp`. Simply put, a `for` construct can be seen as a parallelised `for` loop. We can specify the `for` construct as

~~~c

#pragma omp for [clause[[,]clause]...]

~~~

Here we also start with `pragma omp` followed by the `for` keyword and we can use different clauses again, i.e., private, shared and so on. The corresponding for-loop must have a canonical shape.

~~~c

for (int i=it; i<M; i++)

~~~

Since each iterator is by default a private variable and is shared by only one thread, the iterator is not modified inside the loop body. If it was accessed by every thread, our for-loop would get corrupted.

We have a few other clauses than just `private`. For example:

- `schedule`: It classifies how the iterations of loops are divided among the threads.

- `collapse(n)`: The iterations of `n` loops are collapsed into one larger iteration space.

We can see an example of the `for` construct used in the code.

~~~c

#pragma omp parallel private(f)

{

f=10;

#pragma omp for

for (i=0; i<10; i++) {

a[i] = b[i]*f;

} // end of for

} // end of parallel

~~~

We start with `pragma omp parallel` followed by private variable named `f`. Then we use `pragma omp for` construct, followed by a for loop that goes from 0 to 10 (10 different iterations). The private variable `f` is then fixed in every thread and the list `a` is updated in parallel. This is because the index each array needs is different from each other. So, every thread can access only one place of the array allowing us to update this list in parallel.

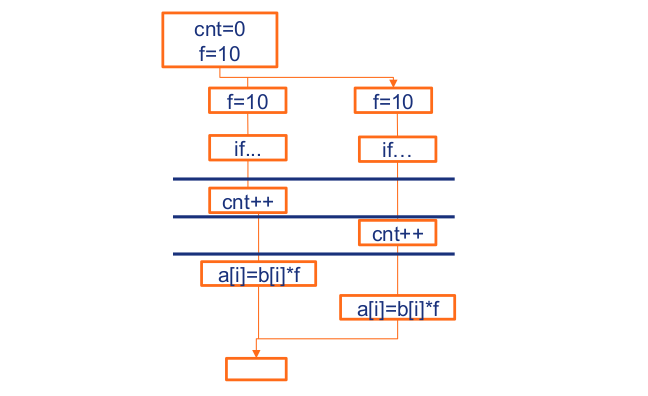

**Image courtesy: Rolf Rabenseifner (HLRS)**

Here we can see that if we are working on two threads with 10 iterations, then these iterations will be split between two threads from 0 to 4 and 5 to 9. Each place on list `a` will be updated by itself and since the iterators are independent of each other, they modify just one place, so we can update each place of the list `a` quite easily.

**Example**

Go to the provided examples and try to understand what is happening in the code. Run the examples and see if your understanding matches the actual output.

[](https://mybinder.org/v2/gh/kosl/ihipp-examples/HEAD?filepath=OpenMP/Worksharing-Constructs.ipynb)

[](https://colab.research.google.com/drive/1Wk-pDfxDRnQHWqXtw-Oa8BcAnwxN1P4D)

### 2.10 Synchronization

Sometimes in parallel programming, when dealing with multiple threads running in parallel, we want to pause the execution of threads and instead run only one thread at a time. This is achieved with so called *barriers*. Synchronization can be achieved by two ways, i.e., through an implicit barrier or an explicit barrier.

- Implicit barrier

We have already seen the use of an implicit barrier in the previous two examples. It is a barrier for beginning and end of parallel constructs, as well as all other control constructs. In C++ this is achieved with curly brackets. As we saw in the previous examples, the `{` is the implicit barrier where we specify the entry into parallel region and the last `}` is basically the implicit barrier that specifies the end of the parallel construct and denotes moving to the serial execution of the code. Implicit synchronization can be removed with a `nowait` clause but we will not discuss it in this section.

- Explicit barrier

For applying an explicit barrier we use a `critical` clause that basically specifies the presence of the barrier. While using an explicit barrier, the code which is enclosed in a critical clause is executed by all threads, but is restricted to only one thread at the time. The critical clause in C/C++ is defined with

~~~c

#pragma omp critical [(name)]

~~~

Let's go over this code quickly.

~~~c

cnt = 0;

f=10;

#pragma omp parallel

{

#pragma omp for

for (i=0; i<10; i++) {

if (b[i] == 0) {

#pragma omp critical

cnt ++;

} /* endif */

a[i] = b[i]*f;

} /* end for */

} /*omp end parallel */

~~~

We see that we have specified variables `cnt` and `f`, and in the parallel region we specified the `for` construct, so we can do the iteration. Inside the `if` statement we specified the `pragma omp critical` for the next line which is `cnt ++`. We can observe what is happening in the execution of the threads on the image below.

**Image courtesy: Rolf Rabenseifner (HLRS)**

Before we enter the `pragma omp parallel` region, we were in serial execution, so that part was executed serially. Then we entered our parallel region. Everything is executed in parallel until the first thread encounters the `cnt++` statement. At this point the `cnt++` statement is executed by the first thread that encounters it. During this time, the second thread can't access it because `cnt` is already being modified by the first thread. So, after the first thread finishes with the critical operation, the next thread will get access to the `cnt` variable and modify it. After all the threads have executed the `cnt++` statement, the code continues to execute in parallel as well. It continues until we reach the implicit barrier that we have specified at the end, following which we return to the serial execution.

We owe it to the critical clause that only one thread is executed at a time for this `cnt` variable. Therefore, when we use the critical clause in a parallel program, only one thread will be able to execute that part of code that you specified in the critical clause.

#### Example

Go to the provided examples and try to understand what is happening in the code. Run the examples and see if your understanding matches the actual output. Have fun and experiment.

[](https://mybinder.org/v2/gh/kosl/ihipp-examples/HEAD?filepath=OpenMP/Synchronization-Constructs.ipynb)

[](https://colab.research.google.com/drive/15V3_fsdzBRIEW0X5t3v-ZrttxLxU_00c)

### 2.11 Nesting and binding

#### Directive Scoping

OpenMP specifies a number of scoping rules on how directives may associate (bind) and nest within each other. That is why incorrect programs may result, if the OpenMP binding and nesting rules are ignored. These terms are used to explain the impact of OpenMP directives.

Static (Lexical) Extent:

* The code textually enclosed between the beginning and the end of a structured block following a directive.

* The static extent of a directive does not span multiple routines or code files.

Dynamic Extent:

* The dynamic extent of a directive further includes the routines called from within the construct.

* It includes both its static (lexical) extent and the extents of its orphaned directives.

Orphaned Directive:

* An OpenMP directive that appears independently from another enclosing directive is said to be an orphaned directive. They are directives inside the dynamic extent but not within the static extent.

* Will span routines and possibly code files.

Let's explain with this example program. We have 2 subroutine calls and both are parallelized.

Program Test:

~~~c

...

#pragma omp parallel

{

...

#pragma omp for

{

for (int i = 0; i < N; i++) {

...

sub1();

...

}

}

...

sub2();

...

}

~~~

These are the two subroutines **sub1** and **sub2**.

~~~c

void sub1() {

...

#pragma omp critical

{

...

}

...

return;

}

~~~

~~~c

void sub2() {

...

#pragma omp sections

{

...

}

...

return;

}

~~~

In this example:

* The static extent of our parallel region is exactly this, the calls inside the parallel region. The FOR directive occurs within an enclosing parallel region.

* The dynamic extent of our parallel region is the static extent plus including the 2 subroutines that are called inside the parallel region. The CRITICAL and SECTIONS directives occur within the dynamic extent of the FOR and PARALLEL directives.

* In the dynamic extent but not in the static extent we have orphaned CRITICAL and SECTIONS directives.

### 2.12 Exercise: Calculate Pi

In this exercise you will get to practice using worksharing construct `for` and `critical` directive.

Pi is a mathematical constant. It is defined as a ratio of a circle's circumference to its diameter. It also appears in many other areas of mathematics. There are also many integrals yielding Pi. One of them is shown below.

$$\pi = \int_{0}^1 \frac{4}{1+x^2}~dx$$

This integral can be approximated numerically using Riemann sum:

$$\pi \approx \sum_{i=0}^{n-1}f(x_i+h/2)h$$

Here, `n` is the number of intervals and `h = 1/n`.

~~~c

#include <stdio.h>

#include <time.h>

#include <sys/time.h>

#include <omp.h>

#define f(A) (4.0/(1.0+A*A))

int main()

{

int num_threads = 4;

omp_set_num_threads(num_threads);

//declarations

const int n = 10000000;

int i;

double w, x, sum, pi;

clock_t t1, t2;

struct timeval tv1, tv2;

struct timezone tz;

double wt1, wt2;

gettimeofday(&tv1, &tz);

wt1 = omp_get_wtime();

t1 = clock();

/* calculate pi = integral [0..1] 4/(1+x**2) dx */

w = 1.0/n;

sum = 0.0;

for (i = 1; i <= n; i++)

{

x = w*((double)i-0.5);

sum = sum+f(x);

}

pi = w*sum;

t2 = clock();

wt2 = omp_get_wtime();

gettimeofday(&tv2, &tz);

printf( "computed pi = %24.16g\n", pi );

printf( "CPU time (clock) = %12.4g sec\n", (t2-t1)/1000000.0 );

printf( "wall clock time (omp_get_wtime) = %12.4g sec\n", wt2-wt1 );

printf( "wall clock time (gettimeofday) = %12.4g sec\n", (tv2.tv_sec-tv1.tv_sec) + (tv2.tv_usec-tv1.tv_usec)*1e-6 );

}

~~~

The code above calculates the solution of the integral in serial. This template should be a starting point for this exercise. The heavy part of computation is performed in the for loop, so this is the part that needs parallelization.

#### Exercise

1. Go to the exercise and add a parallel region and `for` directive to the part that computes Pi. Is the calculation of Pi correct? Test it out more than once, change the number of threads to 2 or 12 and try to find the race condition.

2. Add `private(x)` clause. Is it still incorrect?

3. Add a `critical` directive around the sum statement and compile. Is the value of Pi correct? What is the CPU time? How can you optimize your code?

4. Move the `critical` directive outside the for loop to decrease computational time.

Compare the CPU time for the template program and CPU time for our solution. Have we significantly optimized our code?

#### Expected result

* Faster execution of the parallel program that calculates the correct value of Pi.

[](https://mybinder.org/v2/gh/kosl/ihipp-examples/HEAD?filepath=OpenMP/Exercise-Compute-Pi.ipynb)

[](https://colab.research.google.com/drive/14BgCGwH-SYoCfz14s61gjhDNZY-xHI2E)

### 2.13 Do you understand worksharing directives?

This quiz covers various aspects of worksharing directives that have been discussed so far this week.

1. The purpose of `#pragma omp for` is

( ) Loop work is to be divided into user defined sections

( ) Work to be done in a loop when done, don’t wait

(x) Work to be done in a loop

2. What is the purpose of `#pragma omp sections`?

(x) Loop work is to be divided into user defined sections

( ) Work to be done in a loop when done, don’t wait

( ) Work to be done in a loop

3. What is the output of the following program?

~~~c

#pragma omp parallel num_threads(2)

{

#pragma omp single

printf("read input\n");

printf("compute results\n");

#pragma omp single

Printf("write output\n");

}

~~~

( ) read input, compute results, write output

( ) read input, read input, compute results, write output, write output

(x) read input, compute results, compute results, write output

( ) Error in program

4. What is the purpose of `#pragma omp for nowait`?

( ) Loop work is to be divided into user defined sections

(x) Work to be done in a loop when done, don’t wait

( ) Work to be done in a loop

5. Which directive must come before the directive `#pragma omp sections`?

( ) `#pragma omp section`

(x) `#pragma omp parallel`

( ) None

( ) `#pragma omp master`

6. The following code forces threads to wait till all are done:

( ) `#pragma omp parallel`

(x) `#pragma omp barrier`

( ) `#pragma omp critical`

( ) `#pragma omp sections`

7. What is the output of the following code when run with OMP_NUM_THREADS=4?

~~~c

int arr[4] = {1,2,3,4};

int x=0, y=0, j;

#pragma omp parallel

{

#pragma omp for

for (j = 0; j < 4; j++)

{

#pragma omp critical

x += arr[j];

}

}

#pragma omp parallel

{

#pragma omp single

for (j = 0; j < 4; j++)

{

#pragma omp critical

y += arr[j];

}

}

printf("%d %d", x, y);

~~~

(x) 10, 10

( ) 10, 40

( ) 40, 10

( ) 40, 40

### 2.14 Private and shared variables

#### Data Scope Clauses

We have already learned about the **private** clause where we can specify that each thread should have its own instance of a variable. We have also learned about the **shared** clause where we can specify that one or more variables should be shared among all threads. This is normally not needed because the default scope is shared.

There are several exceptions:

* stack (local) variables in called subroutines are automatically private

* automatic variables within a block are private

* the loop control variables of parallel FOR loops are private

**Private clause**

The private clause always creates a local instance of the variable. For each thread a new variable is created with an uninitialized value. This means these private variables have nothing to do with the original variable except they have the same name and type.

`firstprivate(var)` specifies that each thread should have its own instance of a variable, and that the variable should be initialized with the value of the shared variable existing before the parallel construct.

`lastprivate(var)` specifies that the variable's value after the parallel construct is set equal to the private version of whichever thread executes the final iteration (for-loop construct) or last section (`#pragma sections`).

Nested `private(var)` with same variable name allocate new private storage again.

Let's explain by observing the following code.

~~~ c

#include <stdio.h>

#include <omp.h>

int main()

{

int num_threads = 4;

omp_set_num_threads(num_threads);

int var_shared = -777;

int var_private = -777;

int var_firstprivate = -777;

int var_lastprivate = -777;

#pragma omp parallel shared(var_shared) private(var_private) firstprivate(var_firstprivate)

{

#pragma omp for lastprivate(var_lastprivate)

for (int i = 0; i < 1000; i++)

{

var_shared = i;

var_private = i;

var_firstprivate = i;

var_lastprivate = i;

}

}

printf("after parallel region: %d %d %d %d",

var_shared, var_private, var_firstprivate, var_lastprivate);

}

~~~

Take a moment and try to guess the values of variables after the parallel region. Note the usage of the data scope clauses.

`var_shared` is a shared variable and it is normally updated by the parallel region.

`var_private` is specified as private so every thread has its own instance and after the parallel region the value remains the same as before.

`var_firstprivate` is specified as private and initialized with the value in the shared scope but after the parallel region the value remains the same.

`var_lastprivate` is updated in the last iteration of the for loop to use after the parallel region.

[](https://mybinder.org/v2/gh/kosl/ihipp-examples/HEAD?filepath=OpenMP/Data-scope.ipynb)

[](https://colab.research.google.com/drive/1kpuE27zbDh6hWl34udxwYLUqbktZ2Zrq)

### 2.15 Reduction clause

The reduction clause is a data scope clause that can be used to perform some form of recurrence calculations in parallel. It defines the region in which a reduction is computed and specifies an operator and one or more list reduction variables. The syntax of the `reduction` clause is as follows:

~~~c

reduction (operator : list)

~~~

Variables in list must not be private in the enclosing context. A private variable cannot be specified in a reduction clause. A variable cannot be specified in both a shared and a reduction clause.

For each list item, a private copy is created in each iteration and is initialized with the neutral constant value of the operator. In the table below is the list of each operator and its semantic initializer value.

| Operator | Initializer |

| ----------------- | ---------------------------------------- |

| + | var = 0 |

| - | var = 0 |

| * | var = 1 |

| & | var = ~ 0 |

| `|` | var = 0 |

| ^ | var = 0 |

| && | var = 1 |

| `||` | var = 0 |

| max | var = most negative number |

| min | var = most positive number |

After the end of the region, the original list item is updated with the values of the private copies using the combiner associated with the operator.

Let's observe the following example:

~~~c

#include <stdio.h>

#include <omp.h>

int main()

{

int sum = 0;

#pragma omp parallel for reduction(+:sum)

for (int i = 0; i<20; i++)

{

sum = sum + i;

}

printf("sum: %d", sum);

}

~~~

The reduction variable is `sum` and the reduction operation is `+`. The reduction does the operation automatically. It produces a private variable `sum` inside the loop and in the end it sums up the private partial sum to the global variable.

[](https://mybinder.org/v2/gh/kosl/ihipp-examples/HEAD?filepath=OpenMP/Combined-Constructs.ipynb)

[](https://colab.research.google.com/drive/1VoLZWplaXTsHTS_BVT1dKTC915CUmEG_)

### 2.16 Sum and substract

In this exercise you will get to practice a sum and substract reduction within a combined parallel loop construct.

In the exercise we are generating a number of people and these people are substracting our value of apples. What you need to do is parallelize the code.

~~~c

#include <stdio.h>

#include <omp.h>

double generate_people(int i, int j)

{

return (2 * i + 3 * j); // some dummy return value

}

int main()

{

int num_threads = 4;

omp_set_num_threads(num_threads);

int num = 10;

int people = 0;

int apples = 5000;

for (int i = 0; i < num; i++) {

for (int j = i+1; j < num; j++) {

int ppl = generate_people(i, j);

people += ppl;

apples -= ppl;

}

}

printf("people = %d\n", people);

printf("apples = %d", apples);

}

~~~

#### Exercise

1. Go to the exercise and add a parallel region with *for* clause.

2. Add two reduction clauses: one that adds people, another that substracts apples.

Then answer this:

* What happens when we try to make people "shared"? Why can't you?

[](https://mybinder.org/v2/gh/kosl/ihipp-examples/HEAD?filepath=OpenMP/Reduction.ipynb)

[](https://colab.research.google.com/drive/1Dbl9FSZUWN5UGbHKYfyVnqCseHOF4ldH)

### 2.17 Combined parallel worksharing directives

Combined constructs are shortcuts for specifying one construct immediately nested inside another construct. Specifying a combined construct is semantically identical to specifying the first construct that encloses an instance of the second construct and no other statements. Most of the rules, clauses and restrictions that apply to both directives are in effect. The `parallel` construct can be combined with one of the worksharing constructs, for example `for` and `sections`.

#### `parallel for`

When we are using a parallel region that contains only a single `for` directive , we can substitute the separate directives with this combined directive:

~~~c

#pragma omp parallel for [clause[[,]clause]...]

~~~

This directive admits all the clauses of the `parallel` directive and `for` directive except the `nowait` clause is forbidden.

This combined directive must be directly in front of the `for` loop. An example of the combined construct is shown below:

~~~c

int i;

int f = 7;

#pragma omp parallel for

for (i = 0; i<20; i++) {

c[i] = a[i] + b[i];

}

~~~

### 2.18 Calculate Pi with combined constructs

In this exercise you will get to practice using combined constructs. You will get to use the `reduction` clause and combined construct `parallel for`.

This is a continuation of the previous exercise when we computed Pi using worksharing constructs and critical directive. You will start from the provided solution of that exercise and use the newly learned constructs.

#### Exercise

1. Go to the exercise and remove the critical directive and the additional partial sum variable. Then add the `reduction` clause and compile. Is the value of Pi correct?

2. Now change the parallel region, so that you use the combined construct `parallel for` and compile.

[](https://mybinder.org/v2/gh/kosl/ihipp-examples/HEAD?filepath=OpenMP/Exercise-Compute-Pi-again.ipynb)

[](https://colab.research.google.com/drive/1nMgkNspADemJA1aeYeJH1mL1ic-duEwW)

### 2.19 Heat transfer

In this exercise you will get to practice using directives and clauses that we have learned so far, such as `parallel`, `for`, `single`, `critical`, `private` and `shared`. It is your job to recognize where each of those are required.

Heat equation is a partial differential equation that describes how the temperature varies in space over time. It can be written as

$$df/dt = \Delta f$$

This program solves the heat equation by using explicit scheme: time forwarding and centered space, and it solves the equation on a unit square domain.

The initial condition is very simple. Everywhere inside the square the temperature equals `f=0` and on the edges the temperature is `f=x`. This means the temperature goes from `0` to `1` in the direction of `x`.

The source code is at times hard coded for the purpose of faster loop iterations. Your goal is to:

* parallelize the program

* use different parallelization methods with respect to their effect on execution times

~~~c

#include <stdio.h>

#include <sys/time.h>

#include <omp.h>

// define functions MIN and MAX

#define min(A,B) ((A) < (B) ? (A) : (B))

#define max(A,B) ((A) > (B) ? (A) : (B))

// define size of grid points

#define imax 20

#define kmax 11

#define itmax 20000

// function prints the temperature grid, don't parallelize

void heatpr(double phi[imax+1][kmax+1]){

int i,k,kl,kk,kkk;

kl = 6; kkk = kl-1;

for (k = 0; k <= kmax; k = k+kl){

if(k+kkk > kmax) kkk = kmax-k;

printf("\ncolumns %5d to %5d\n", k, k+kkk);

for (i = 0; i <= imax; i++){

printf("%5d ", i);

for (kk = 0; kk <= kkk; kk++){

printf("%#12.4g", phi[i][k+kk]);

}

printf("\n");

}

}

return;

}

int main()

{

// define variables

double eps = 1.0e-08;

double phi[imax+1][kmax+1], phin[imax][kmax];

double dx, dy, dx2, dy2, dx2i, dy2i, dt, dphi, dphimax, dphimax0;

int i, k, it;

struct timeval tv1, tv2; struct timezone tz;

double wt1, wt2;

printf("OpenMP-parallel with %1d threads\n", omp_get_num_threads());

dx = 1.0/kmax; dy = 1.0/imax;

dx2 = dx*dx; dy2 = dy*dy;

dx2i = 1.0/dx2; dy2i = 1.0/dy2;

dt = min(dx2,dy2)/4.0;

// setting initial conditions

/* start values 0.d0 */

for (i = 1; i < imax; i++){

for (k = 0; k < kmax; k++){

phi[i][k] = 0.0;

}

}

/* start values 1.d0 */

for (i = 0;i <= imax; i++){

phi[i][kmax] = 1.0;

}

/* start values dx */

phi[0][0] = 0.0;

phi[imax][0] = 0.0;

for (k = 1; k < kmax; k++){

phi[0][k] = phi[0][k-1]+dx;

phi[imax][k] = phi[imax][k-1]+dx;

}

// print starting values

printf("\nHeat Conduction 2d\n");

printf("\ndx = %12.4g, dy = %12.4g, dt = %12.4g, eps = %12.4g\n",

dx, dy, dt, eps);

printf("\nstart values\n");

heatpr(phi);

gettimeofday(&tv1, &tz);

wt1 = omp_get_wtime();

/* time step iteration */

for (it = 1; it <= itmax; it++){

dphimax = 0.;

dphimax0 = dphimax;

for (k = 1; k < imax; k++){

for (i = 0; i < kmax; i++){

dphi = (phi[i+1][k]+phi[i-1][k]-2.*phi[i][k])*dy2i

+(phi[i][k+1]+phi[i][k-1]-2.*phi[i][k])*dx2i;

dphi = dphi*dt;

dphimax0 = max(dphimax0,dphi);

phin[i][k] = phi[i][k]+dphi;

}

}

dphimax = max(dphimax,dphimax0);

/* save values */

for (i = 1; i < imax; i++){

for (k = 0; k < kmax; k++){

phi[i][k] = phin[i][k];

}

}

if(dphimax < eps) break;

}

wt2 = omp_get_wtime();

gettimeofday(&tv2, &tz);

// print resulting grid and execution time

printf("\nphi after %d iterations\n", it);

heatpr(phi);

printf( "wall clock time (omp_get_wtime) = %12.4g sec\n", wt2-wt1 );

printf( "wall clock time (gettimeofday) = %12.4g sec\n", (tv2.tv_sec-tv1.tv_sec) + (tv2.tv_usec-tv1.tv_usec)*1e-6 );

}

~~~

The code above calculates the temperature for a grid of points, the main part of code being the time step iteration. `dphi` is the difference of temperature and `phi` is the temperature. Then we add the `dphi` to the `phi` array and we save the new `phin` array. Then in the next for loop we exchange the role of the old and the new array (restoring the data).

#### Exercise

1\. Go to the exercise and parallelize the code.

2\. Parallelize all of the for loops and use critical section for global maximum. Think about what variables should be in the private clause.

Then run the example. Run it with 1, 2, 3, 4 threads and look at the execution time.

You may see that with more threads it is slower than expected. Do you have any idea about why the parallel version is slower by looking at the code?

~~~c

for (k = 1; k < imax; k++){

for (i = 0; i < kmax; i++){

dphi = (phi[i+1][k]+phi[i-1][k]-2.*phi[i][k])*dy2i

+(phi[i][k+1]+phi[i][k-1]-2.*phi[i][k])*dx2i;

dphi = dphi*dt;

dphimax0 = max(dphimax0,dphi);

phin[i][k] = phi[i][k]+dphi;

}

}

~~~

The sequence of the nested loops is wrong. In C/C++, the last array index is running the fastest so the `k` loop should be the inner loop. This is not fixed by the OpenMP compiler, so you will need to

3\. Interchange the sequence of the nested loops.

Run the code again with 1, 2, 3, 4 threads and look at the execution time.

Now the parallel version should be a little bit faster. The reason for only a slight improvement might be that the problem is too small and the parallelization overhead is too large.

[](https://mybinder.org/v2/gh/kosl/ihipp-examples/HEAD?filepath=OpenMP/Exercise-Heat.ipynb)

[](https://colab.research.google.com/drive/1Pmrkef-YyYN6MhYEJYzSPjGoJ5H1oxbD)

### 2.20 Do you understand combined constructs?

This quiz tests your knowledge on OpenMP data environment and combined constructs.

1. Within a parallel region, declared variables are by default

( ) private

( ) local

(x) shared

( ) firstprivate

2. What is the output of the following code when run with OMP_NUM_THREADS=4?

~~~c

int arr[4] = {1,2,3,4};

int x = 1, j;

#pragma omp parallel for reduction(*:x)

for(j = 0; j < 4; j++) {

x *= arr[j];

}

printf("%d", x);

~~~

(x) 24

( ) 0

( ) 10

( ) 4

3. What does the `nowait` clause do?

( ) Skips to the next OpenMP construct

( ) Prioritizes the following OpenMP construct

( ) Removes the synchronization barrier from the previous construct

(x) Removes the synchronization barrier from the current construct

4. What is the data scoping of the variables a, b, c and d in following code snippet in the parallel region?

~~~c

int a = 0;

int b = 23;

int c = -3;

#pragma omp parallel num_threads(2) private(a) reduction(+:c)

{

int d = omp_get_thread_num();

a = 42 + d;

#pragma omp critical

b = 1;

c += a + b;

}

c = c / 2;

printf("a=%d, b=%d, c=%d\n", a, b, c);

~~~

[ ] a: shared

[x] a: private

[x] b: shared

[ ] b: private

[ ] c: shared

[ ] c: private

[x] c: reduction

[ ] d: shared

[x] d: private

5. What is printed when executing the below code?

~~~c

int a = 0;

int b = 23;

int c = -3;

#pragma omp parallel num_threads(2) private(a) reduction(+:c)

{

int d = omp_get_thread_num();

a = 42 + d;

#pragma omp critical

b = 1;

c += a + b;

}

c = c / 2;

printf("a=%d, b=%d, c=%d\n", a, b, c);

~~~

( ) a=0, b=23, c=-3

( ) a=44, b=23, c=84

( ) a=0, b=23, c=42

(x) a=0, b=1, c=42

6. Which of the following clauses specifies that the enclosing context’s version of the variable is set equal to the private version of whichever thread executes the final iteration?

( ) private

( ) firstprivate

(x) lastprivate

( ) default

7. The following code will result in a data race:

~~~c

#pragma omp parallel for

for (int i = 1; i < 10; i++)

{

factorial[i] = i * factorial[i-1];

}

~~~

(x) True

( ) False

8. Which of these parallel programming errors is impossible in the given OpenMP construct?

( ) Data dependency in #pragma omp for

(x) Data conflict in #pragma omp critical

( ) Data race in #pragma omp parallel

( ) Deadlock in #pragma omp parallel

### 2.21 Tasking model

Tasking allows the parallelization of applications where work units are generated dynamically, as in recursive structures or while loops.

In OpenMP an explicit task is defined using the task directive.

~~~c

#pragma omp task[clause[[,]clause]...]

structured-block

~~~

The task directive defines the code associated with the task and its data

environment. When a thread encounters a task directive, a new task is

generated. The task may be executed immediately or at a later time. If

task execution is delayed, then the task is placed in a conceptual

pool of sleeping tasks that is associated with the current parallel region. The threads in the current teams will take tasks out of the pool and

execute them until the pool is empty. A thread that executes a task

might be different than the one that originally encountered it.

The code associated with the task construct will be executed only

once. A task is named to be *tied*, if it is executed by the same thread

from beginning to end. A task is *untied* if the code can be executed by

more than one thread, so that different threads execute different

parts of the code. **By default, tasks are tied**.

We also want to mention that there are several task scheduling points where a task can be put from living into sleeping and back from sleeping to a living state:

- In the generating task: after the task generates an explicit task, it can be put into a sleeping state.

- In the generated task: after the last instruction of the task region.

- If task is *untied*: everywhere inside the task.

- In implicit and explicit barriers.

- In `taskwait`.

Completion of a task can be guaranteed using task synchronization constructs such as `taskwait` directive. The taskwait construct specifies a wait on the completion of child tasks of the current task. The taskwait construct is a stand-alone directive.

~~~c

#pragma omp taskwait [clause[ [,] clause] ... ]

~~~

### 2.22 Data environment

There are additional clauses that are available with the task directive:

* `untied`

If the task is tied, it is guaranteed that the same thread will execute all the parts of the task. So, the untied clause allows code to be executed by more than one thread.

* `default (shared | none | private | firstprivate)`

Default defines the default data scope of a variable in each

task. Only one default clause can be specified on an OpenMP task directive.

* `shared (list)`

Shared declares the scope of the comma-separated data variables in

`list` to be shared across all threads.

* `private (list)`

Private declares the scope of the data variables in `list` to be

private in each thread.

* `firstprivate (list)`

Firstprivate declares the scope of the data variables to be private

in each thread. Each new private object is initialized with the value

of the original variable.

* `if (scalar expression)`

Only if the scalar expression is true will the task be started, otherwise a normal sequential execution will be done. Useful for a good load balancing but limiting the parallelization overhead by doing a limited number of the tasks in total.

### 2.23 Fibonacci example

In the following example, the tasking concept is used to compute Fibonacci numbers recursively.

~~~c

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <omp.h>

int fib(int n) {

if (n < 2) return n;

int x, y;

#pragma omp task shared(x) firstprivate(n)

{

x = fib(n - 1);

}

#pragma omp task shared(y) firstprivate(n)

{

y = fib(n - 2);

}

#pragma omp taskwait

return x+y;

}

int main()

{

omp_set_num_threads(4);

int n = 8;

#pragma omp parallel shared(n)

{

#pragma omp single // Only one thread executes single, we only need to print once

printf ("fib(%d) = %d\n", n, fib(n));

}

}

~~~

The parallel directive is used to define the parallel region which

will be executed by four threads. Inside `parallel` construct, the

`single` directive is used to indicate that only one of the threads will execute the print statement that calls `fib(n)`.

In the code, two tasks are generated using the task directive. One of the tasks computes `fib(n-1)` and the other computes `fib(n-2)`. The return values of both tasks are then added together to obtain the value returned by `fib(n)`. Every time functions `fib(n-1)` and `fib(n-2)` are called, two tasks are generated recursively until argument passed to `fib()` is less than 2.

Furthermore, the `taskwait` directive ensures that the two tasks

generated are first completed, before moving on to new stage of

recursive computation.

Go to the example to see it being done step by step and try it out for yourself.

[](https://mybinder.org/v2/gh/kosl/ihipp-examples/HEAD?filepath=OpenMP/Fibonacci.ipynb)

[](https://colab.research.google.com/drive/1mpZzd1bNWMm2yCzzRrM7XgPN_AhyvBuw)

### 2.24 Exercise: Traversing of a tree

The following exercise shows how to traverse a tree-like structure using explicit tasks.

In the previous step we looked at the Fibonacci example, now we traverse a linked list computing a sequence of Fibonacci numbers at each node.

Parallelize the provided program using parallel region, tasks and other directives. Then compare your solution’s complexity compared to the approach without tasks.

#### Exercise

1. Go to the exercise and parallelize the part where we do process work for all the nodes.

2. The printing of the number of threads should be only done by the master thread. Think about what else must be done by one thread only.

3. Add a task directive.

Did the parallelization give faster results?

[](https://mybinder.org/v2/gh/kosl/ihipp-examples/HEAD?filepath=OpenMP/Traversing-tree.ipynb)

[](https://colab.research.google.com/drive/1UZR_WXqV8BWOKOOZaugeIXxAeVlU4rMJ)

### 2.25 Quiz on OpenMP tasking

This quiz tests your knowledge on OpenMP tasking with which we will finish this week’s material.

1. The default clause sets the default scheduling of threads in a loop constructs.

( ) True

(x) False

2. Which tasks are synchronized with a `taskwait` construct?

( ) All tasks of the same thread team.

( ) All descendant tasks.

(x) The direct child tasks.

3. Look at the following code snippet.

~~~c

int x = 42;

#pragma omp parallel private(x)

{

#pragma omp task

{

x = 3;

}

}

printf("x=%d\n", x);

~~~

What is the data scope of x in the task region and what is printed at the end?

( ) shared, x=3

( ) firstprivate, x=3

(x) firstprivate, x=42

4. Look at the following code snippet.

~~~c

int x = 42;

int y = 0;

#pragma omp parallel num_threads(4)

{

#pragma omp task

{

#pragma omp critical

{

y += x;

}

}

}

printf("y=%d\n", y);

~~~

What is the data scope of y in the task region and what is printed at the end?

( ) shared, y=42

(x) shared, y=168

( ) firstprivate, y=168

5. What happens to tasks at a `barrier` construct?

( ) All existing tasks are guaranteed to be completed at barrier exit.

(x) All tasks of the current thread team are guaranteed to be completed at barrier exit.

( ) Only the direct child tasks are guaranteed to be completed at barrier exit.

### 2.26 Test on OpenMP

With this test we will check your knowledge about using OpenMP for parallel programming.

Test available on FutureLearn in the MOOC [Introduction to Parallel Programming](https://www.futurelearn.com/courses/interactive-hands-on-introduction-to-parallel-programming).

### 2.27 Week 2 wrap-up

In Week 2 we presented the concepts, programming and execution model of OpenMP in detail. With hands on examples we have tried to show how to use this paradigm as efficiently as possible.

Please, discuss the OpenMP parallel programming paradigm and try to summarize its potential in general or maybe specifically for your applications.

We are also very much interested to know if you found Week 2 content useful?