# AI4Science101-Quantum Chemistry

## What is quantum chemsitry?

A water molecule looks so much different from a protein molecule or a diamond crystal, but mathematically they are all the same: a set of positively charged nuclei being "glued" through Coulomb interaction by a set of negatively charged electrons. The electron "glue" is known as *chemical bonds*. In a nutshell, chemistry is the study and use of the electron "glue" to make new chemical species of desired properties. Quantum chemistry - often also known as *electronic structure theory* - aims to understand the electron "glue" itself using quantum mechanics.

The core of quantum chemistry is to solve the time-independent Schrödinger equation for electrons, $H \Psi_n = E_n \Psi_n$, which is an eigenvalue problem for the electronic Hamiltonian $H$ that defines a chemical system. The eigenfunction $\Psi_n$ is the system's *wavefunction* and the eigenvalue $E_n$ is the associated *energy*, with the lowest-energy solution, denoted by $\Psi_0$, being called the "ground" state and all others the "excited" states. In this article, we will mostly focus on solving for the ground-state wavefunction $\Psi_0$ and its energy $E_0$ (from now on we will occasionally omit the subscript "0"), the knowledge of which provides key information for understanding many physical and chemical properties of a molecule or a material. For example,

- Knowing the energy of the reactant and the product in a chemical reaction allows calculating the reaction energy, while knowing how the energy responds to external parameters provides access to atomic forces, dipole moments, and polarizabilities, to name a few, of a molecule.

- Knowledge of the wavefunction enables analyzing the orbitals, electron densities, electron correlation and entanglement, *etc*., all of which help provide a microscopic understanding of a chemical system.

<!-- The core of quantum chemistry is to solve the time-independent Schrödinger equation, $H \Psi_n = E_n \Psi_n$, whose solution, the energy $E$ and the wavefunction $\Psi$, provides key information for understanding most physical and chemical properties of a molecule or a material. For example, knowing $E$ of the reactants and products of a chemical reaction allows us to calculate reaction energies, while knowing the response (i.e., derivative) of $E$ with respect to external parameters gives us access to atomic forces (for molecular dynamics) and various spectroscopic properties such as IR and Raman. On the other hand, knowledge of $\Psi$ gives us access to orbitals, electron densities, electron correlation and entanglament that help provide a miscroscopic understanding of a physical of chemical process. -->

Despite all the promises it makes, the Schrödinger equation for a general chemical system containing many electrons is computationally very challenging to solve. As we will see soon, the cost of obtaining an exact solution grows *exponentially* with the system size, and approximate solutions must be sought for in practice. Thus, the thesis of quantum chemistry is **making approximations that balance accuracy and computational cost**. This is exactly where recent developments in the machine learning (ML) community has stepped in and shown a great potential of addressing some perspectives of this challenge. In the rest of this article, we will first introduce basic context of quantum chemistry, followed by outlining recent progress in ML. We believe that this article will make quantum chemistry and ML research more accessible to readers from diversified backgrounds.

<!-- Quantum chemistry is a branch of chemistry that aims to understand and predict the behavior of electrons, atoms and molecules, and thus to describe the electronic structure and behavior of matter, particularly in the context of chemical reactions and interactions. The core of quantum chemistry is to solve the time-independent Schrödinger equation, $H \Psi = E \Psi$. Despite it is a eigenvalue problem that everyone of us has learned to solve during the linear algebra class, the difficuly lies in the extremely high numberof degree of freedom for the electronic Hamiltonian $H$, which has an exponential scaling on the size of system. This is called the *curse of dimensionality*. Solving this Schrödinger equation obtaining the ground state wave function $\Psi$, however, is the key to understand most of the physical and chemical properties of molecules and materials, such as light absorption/emission and conductivity. Getting the ground state energy, $E$, allows us to predict which chemical reactions are possible and how one should manipulate the external environment to control reactions of interest. Recently, machine learning (ML) has stepped in this long-standing problem and shown promising sign of addressing some perspectives of this challenge. In the rest of this article, we will introduce basic context of quantum chemistry, followed by outlining these recent progress in ML. -->

<!-- QC part for Hongzhou to draft -->

## Dive in to quantum chemistry

This section is designed to offer a tailored introduction to quantum chemistry for readers who are familiar with linear algebra and probability theory but may not be well-versed in quantum mechanics. We begin with introducing some [basic concepts of quantum chemistry](#basic-concepts-of-quantum-chemistry), including variational principle, orbitals, and Hartree-Fock theory. This is followed by a survey of [methods for electron correlation](#methods-for-electron-correlation) that can achieve "chemical accuracy", with the goal of acquainting readers with many of the "buzz words" in quantum chemistry, such as DFT, CCSD(T), FCI, DMRG, QMC, to name a few. That's quite a bit of information, so buckle up and let's go!

> For readers interested in diving deeper into quantum chemistry systematically, we recommend the classical textbook by Szabo and Ostlund, titled *[Modern Quantum Chemistry: Introduction to Advanced Electronic Structure Theory](https://store.doverpublications.com/0486734420.html)*. We believe that the materials presented below serve as a good preview.

### Basic concepts of quantum chemistry

**Electronic Hamiltonian**. The electronic Hamiltonian $H$ includes all energy components related to the electrons in a molecule or material. For an $N$-electron system, $H$ has two major contributions: the sum of individual electron Hamiltonians and the pairwise Coulomb interactions between electrons, i.e.,

$H(x_1,\cdots,x_N) = \sum_{i=1}^{N} h(x_i) + \frac{1}{2} \sum_{i \neq j}^{N} v(x_i,x_j)$

<!-- The specific forms of $h$ and $v$ are not crucial for our discussion below. However, it's worth making two comments about the Hamiltonian: -->

<!-- 1. The Coulomb interaction makes the probability of finding a single electron **correlated** with finding other electrons. This correlation is what makes the Schrödinger equation hard to solve. -->

The specific forms of $h$ and $v$ are not crucial for our discussion below. However, it's worth noting that $h$ includes the Coulomb attraction between an electron and the nuclei, which introduces a parametric dependence of the full Hamiltonian $H$ on the atomic coordinates $R$. Solving the Schrödinger equation for various atomic configurations yields an energy profile as a function of these coordinates, denoted as $E(R)$. This energy profile is commonly referred to as the "*potential energy surface*" and its derivatives $\nabla_{R} E$ give the atomic forces, forming the basis for molecular dynamics, a topic discussed in a [previous post](https://ai4science101.github.io/blogs/molecular_simulation/) on our blog.

<!-- We only mention that $h$ includes the Coulomb attraction of an electron by all the nuclei and hence depends parametrically on the atomic coordinates $R$. Thus, when we say a "system" in what follows, we really mean a Hamiltonian with some fixed $R$, i.e., a snapshot of a molecule with all the nuclei being "clamped". For example, both the folded and unfolded states of a protein contains the same set of atoms but are two different "systems" since the atomic coordinates have changed. -->

<!-- **Electronic Hamiltonian**. The electronic Hamiltonian is a sum of all energy components of the electrons in a chemical system. This includes the electrons' kinetic energy $T$, their interaction with the nuclei, $V_{\mathrm{nuc}}$, -->

**Wavefunction is probability amplitude**. God does play dice, and her dice is wavefunction. For an $N$-electron system, the probability density of simultaneously finding electron 1 at position $x_1$, electron 2 at position $x_2$, *etc*. is

<!-- $\rho(x_1,\cdots,x_N) = |\Psi(x_1,\cdots,x_N)|^2$ -->

$\rho(X) = |\Psi(X)|^2$

with the normalization condition

<!-- $\int \mathrm{d}x_1\cdots\mathrm{d}x_N\, |\Psi(x_1,\cdots,x_N)|^2 = 1$ -->

$\int \mathrm{d}^N X\, |\Psi(X)|^2 = 1$

where $X = (x_1,\cdots,x_N)$. For this reason, wavefunction is a probability *amplitude* that encodes the *correlation* between electrons. Many properties of a molecule or a material can be calculated directly from its wavefunction as an expectation

<!-- $A

= \int \mathrm{d}x_1\cdots\mathrm{d}x_N\, |\Psi(x_1,\cdots,x_N)|^2

A(x_1,\cdots,x_N)

\equiv \langle \Psi | A | \Psi \rangle$ -->

$A

= \int \mathrm{d}^N X\, |\Psi(X)|^2

A(X)

\equiv \langle \Psi | A | \Psi \rangle$

where the ["bra-ket" notation](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bra%E2%80%93ket_notation) $\langle \Psi |\cdot| \Psi\rangle$ is due to Dirac. An relevant example for the discussion below is that the energy is an expectation of the Hamiltonian, $E = \langle \Psi | H | \Psi\rangle$.

**Variational principle**. A powerful tool to guide the construction of approximate wavefunction is *variational principle*, which states that the energy of any inexact "trial" wavefunction $\tilde{\Psi}$ is no lower than the ground-state energy, i.e.,

$E[\tilde{\Psi}]

= \langle \tilde{\Psi} | H | \tilde{\Psi} \rangle

\geq E_0$

where the equality is taken if and only if $\tilde{\Psi} = \Psi_0$. This theorem allows us to *optimize* an approximate wavefunction by *minimizing* its energy, a point we will frequently return to later.

<!-- **Slater determinants**. The Hamiltonian of an $N$-electron system can be broken down into two parts, the sum of one-electron Hamiltonians and the Coulomb interaction between them, i.e.,

$H = \sum_{i}^{N} h(x_i) + \frac{1}{2} \sum_{i \neq j}^{N} v(x_i,x_j)$

In an imaginary world where electrons do not interact (i.e., no second term), the Schrödinger equation is solved by a [**Slater determinant**](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Slater_determinant) -->

**Slater determinants**. In an imaginary world where electrons do not interact, i.e., with the following non-interacting Hamiltonian

$H_{\mathrm{NI}} = \sum_{i = 1}^{N} h(x_i)$

the Schrödinger equation is solved by a [**Slater determinant**](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Slater_determinant)

$\Phi(X)

\equiv \Phi(x_1,\cdots,x_N)

= \frac{1}{\sqrt{N!} }

\begin{vmatrix}

\phi_1(x_1) & \cdots & \phi_1(x_N) \\

\vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\

\phi_N(x_1) & \cdots & \phi_N(x_N)

\end{vmatrix}$

where the one-electron wavefunction, *aka* **orbitals**, $\{\phi_i\}$ are solutions to the one-electron Schrödinger equation

$h(x) \phi_i(x) = \epsilon_i \phi_i(x)$

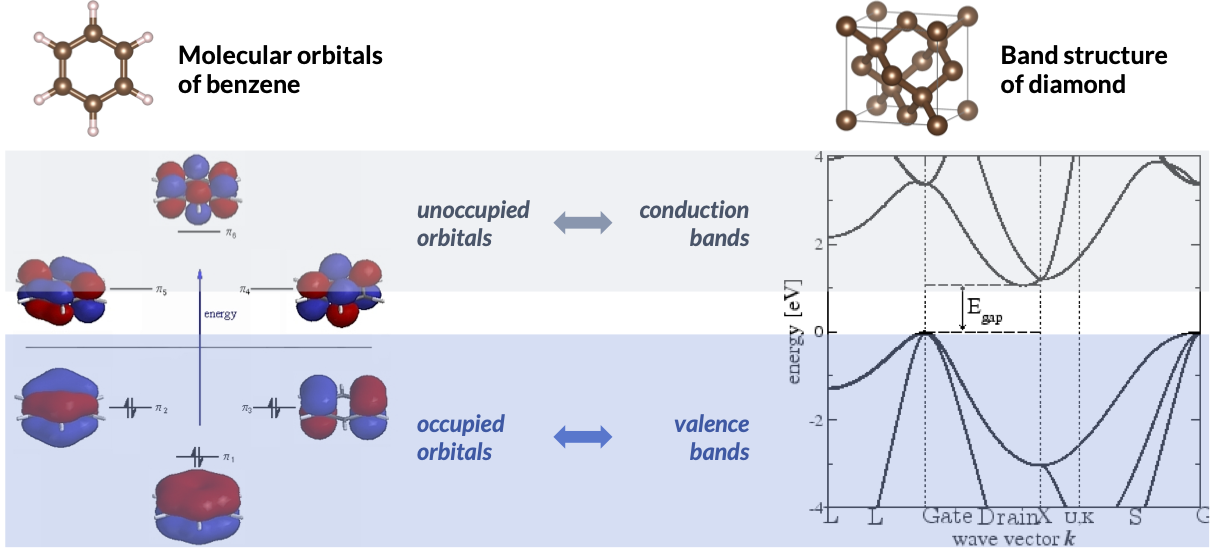

with the eigenvalues $\{\epsilon_i\}$ the **orbital energies** (which also form the energy bands in crystalline solids).

> Readers familiar with probability theory may find the *Hartree product*, $\Phi_{\mathrm{H}}(X) = \prod_{i=1}^{N} \phi_i(x_i)$, be their first guess for a non-interacting wavefunction. Indeed, one can show that the Slater determinant arises from antisymmetrizing the Hartree product, $\Phi(X) = \mathcal{A} [\Phi_{\mathrm{H}}](X)$, where $\mathcal{A}[f](x_1,x_2) = -\mathcal{A}[f](x_2,x_1)$. The reason behind this can be traced back to the [Pauli exclusion principle](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pauli_exclusion_principle), which states that the interchange of any electron pair leads to a change in the wavefunction's sign. The distinction between $\Phi$ and $\Phi_{\mathrm{H}}$ is called the *exchange* effect, which is purely a quantum phenomenon. We will revisit this concept when discussing density functional theory (DFT) later.

**Orbitals**. In practice, the one-electron Schrödinger equation can be solved by expanding the unknown orbitals $\phi_i(x)$ in a known set of $K$ basis functions $\chi_{\mu}(x)$ as $\phi_i(x) = \sum_{\mu}^{K} c_{\mu i} \chi_{\mu}(x)$, turning the Schrödinger equation into a (Hermitian) matrix eigenvalue problem

$\sum_{\nu}^{K} h_{\mu\nu} c_{\nu i}

= \epsilon_i c_{\mu i}$ ( where $h_{\mu\nu} = \langle \chi_{\mu} | h | \chi_{\nu} \rangle$ )

which can be solved readily by e.g., `scipy.linalg.eigh`. In almost all cases, we have $K > N$ to minimize the basis incompleteness error. This leads to the concept of *occupied* and *unoccupied* orbitals.

In the figure on the left, we show the valence orbitals and the corresponding orbital energy diagram for a benzene molecule generated using a minimal set of 6 basis functions. In the non-interacting ground-state $\Phi_0$, the 6 valence electrons occupy the 3 orbitals with lowest energy. This is the theoretical foundation of the well-known picture where electrons in a molecule fill in the orbitals by their energy from low to high. The remaining 3 *unoccupied orbitals* do not contribute to $\Phi_0$ but will become important in the correlated wavefunction theories that we will explore later. In the figure on the right, we show the orbital energy diagram for the diamond crystal. Here, the crystalline orbitals can be organized by symmetry labels of the crystal, and their orbital energy collectively forms what we known as **energy bands**. The occupied and unoccupied bands are often referred to as *valence* and *conduction* bands, respectively.

Of particular interest are the "frontier" orbitals located near the energy gap between the occupied and unoccupied manifolds. For example, the highest occupied and the lowest unoccupied molecular orbitals, i.e., **HOMO** and **LUMO**, are often the most active orbitals in a chemical reaction. Their counterparts in materials, the valence band maximum (VBM) and the conduction band minimum (CBM), determine the **band gap** and the **effective mass** for electron and hole transport.

> We won't delve into specifics here, but it's worth noting that the basis functions $\{\chi_{\mu}\}$ used to expand the orbitals are commonly referred to as *Gaussian basis sets* or *atomic orbitals* in molecular calculations and as *plane waves* in materials. Gaussian basis sets come in various flavors, often denoted by acronyms (e.g., 6-311G**, cc-pVTZ, def2-QZVPP, etc), while the plane-wave basis is characterized by a single parameter, its kinetic energy cutoff.

**Hartree-Fock (HF) theory**. Now going back to the physical world where electrons do interact, the single-determinant wavefunction $\Phi$ is not exact anymore, but we can nonetheless use it as a trial wavefunction and apply variational principle. This leads to the **Hartree-Fock (HF) theory** with the following *effective* one-electron Schrödinger equation

$F[\{\phi_i\}](x) \phi_i(x) = \epsilon_i \phi_i(x)$

where the Fock operator $F[\{\phi_i\}] = h + v_{\mathrm{HF}}[\{\phi_i\}]$ replaces the bare one-electron Hamiltonian $h$. Like in the non-interacting case, the HF equation can be turned into a matrix eigenvalue problem by introducing a basis, and the picture where electrons fill in orbitals by energy discussed above still holds. However, two new features are worth some words.

1. The actual Coulomb potential $v(x_1,x_2)$ in the HF theory is replaced by an effective Coulomb potential, $v_{\mathrm{HF}}(x)$, *averaged* over all other $N-1$ electrons. This is why HF is often referred to as the *mean-field approximation*.

2. The Fock operator that needs to be diagonalized depends on its own eigenfunctions (i.e., orbitals), which necessitates the iterative solution of the HF equation until self-consistency is achieved. This is why HF is also often referred to as the *self-consistent field (SCF)* theory.

A shocking fact about the HF theory is that it recovers > 99% of the total energy of a molecule or a material (Similar to the accuracy that you will get by plugging in a naive CNN to the MNIST dataset)! For this reason, HF provides a decent *qualitative* description for most chemistry problems. However, **getting the remaining 1% correctly** is what really makes a theory *quantitative* and *predictive*. The reason here is about relevant energy scales: the total energy of a molecule is often hundreds or even thousands of *Hartree*, while chemical reactions occur on the scale of *kcal/mol* (1 Hartree ≈ 630 kcal/mol). In quantum chemistry, people often refer 1 kcal/mol as "chemical accuracy." In the next subsection, we will introduce theories that are capable of achieving this level of precision, which form the core of quantum chemistry.

> It is interesting to note that [one of Google's "quantum computing for quantum chemistry" papers](https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.abb9811) implemented exactly the HF theory on a quantum computer and used it to study a simple reaction. Now you know (the chemistry part of) what they were doing!

### Methods for electron correlation

**Overview**. Two primary strategies exist for going beyond the HF mean-field approach. **Correlated wavefunction theories** employ a more sophisticated wavefunction *ansatz* than the HF single Slater determinant. In contrast, **density functional theory (DFT)** -- in its most widely used *Kohn-Sham (KS)* formulation -- retains the single determinantal wavefunction but alters the HF potential into a KS potential that accounts for electron correlation effects. Both approaches have their strengths and weaknesses, which can potentially be harnesses or addressed through integration with ML. We believe that having a fundamental grasp of each of these methods is essential for achieving this goal.

***

<!-- **Density functional theory (DFT)**. The theories introduced thus far are all about improving the wavefunction to approach FCI. An alternative formalism was introduced by Hohenberg and Kohn (HK) in 1964, who demonstrated that the **electron density** -->

**Density functional theory (DFT)**. Up to this point, our discussion has primarily revolved around wavefunctions. However, an alternative formalism was introduced by Hohenberg and Kohn (HK) in 1964, who demonstrated that the **electron density**

$\rho(x)

= \int \mathrm{d}x_2\cdots\mathrm{d}x_{N}\,

|\Psi(x,x_2,\cdots,x_N)|^2$

could serve as the fundamental quantity instead. Specifically, HK proved [two mathematical theorems](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Density_functional_theory#Hohenberg%E2%80%93Kohn_theorems) about $\rho(x)$:

1. The first theorem (HK-I) establishes the *equivalence* between $\rho$ and $\Psi$ by proving that given a system's electron density, one can uniquely determine the Hamiltonian (up to a constant energy shift) and hence in principle, determine the wavefunction.

2. The second theorem (HK-II) establishes a *variational principle* for $\rho$ by showing that the ground-state electron density $\rho_0$ minimizes the energy functional $E[\rho]$, i.e., just like $\Psi_0$ minimizing $E[\Psi]$.

Unfortunately, the precise expression for $E[\rho]$ remains unknown. However, HK theorems provide a valuable decomposition of $E[\rho]$, as follows:

$E[\rho] = \int\mathrm{d}x\, \rho(x) v_{\mathrm{ext}}(x) + F[\rho]$

Here, the first term accounts for the energy resulting from the external potential that is system-dependent (e.g., the nuclear potential in a molecule), while the second term, known as the **universal energy functional**, encompasses all the electron-electron interaction and is universal for all molecules and materials for their ground-state properties.

**Kohn-Sham (KS)-DFT**. At the heart of DFT lies the quest for practical approximations to $F[\rho]$. Thus far, the most popular variant is *KS-DFT*, where one aims to construct a non-interacting system -- described by a Hartree product $\Phi_{\mathrm{H}}$ -- whose electron density is equal to the exact ground-state density $\rho_0$. The KS energy functional is

$E_{\mathrm{KS}}[\rho]

= \langle\Phi_{\mathrm{H}}|H|\Phi_{\mathrm{H}}\rangle

+ E_{\mathrm{xc}}[\rho]

= \sum_{i} \langle\phi_i|h|\phi_i\rangle

+ J[\rho] + E_{\mathrm{xc}}[\rho]$

In the second equality, the first term is simply a sum of one-electron energy and the second term is the classical electrostatic energy which includes *self-interaction*. The last term, known as the **exchange-correlation (xc) functional**, encapsulates the missing exchange and electron correlation effects and necessitates practical approximation. On initial inspection, it might seem like this rewriting doesn't solve any problem: the exact form of $E_{\mathrm{xc}}[\rho]$ remains elusive. Nevertheless, the KS approach proves effective because $E_{\mathrm{xc}}[\rho]$ is relatively small in magnitude (similar to the correlation energy). Consequently, it can be reasonably approximated in practice.

Applying variational principle, i.e., making $E_{\mathrm{KS}}[\rho]$ stationary w.r.t the underlying orbitals leads to the KS equation

$F_{\mathrm{KS}}[\rho](x) \phi_i(x) = \epsilon_i \phi_i(x)$

where the KS operator, $F_{\mathrm{KS}}[\rho] \equiv \delta E_{\mathrm{KS}}[\rho] / \delta \rho = h + v_{J}[\rho] + v_{\mathrm{xc}}[\rho]$, parallels the Fock operator in HF theory. The KS equation can be solved in a manner analogous to solving the HF equation, with the $\rho$-dependence of the KS operator also necessitating an iterative approach to achieve self-consistency. Similar to HF, KS-DFT is an *effective* one-electron theory where the quantum (i.e., exchange) and many-body (i.e., correlation) effects of electrons are encapsulated in the *xc potential*, $v_{\mathrm{xc}}[\rho] = \delta E_{\mathrm{xc}}[\rho] / \delta \rho$. This renders KS-DFT rather convenient because it preserves all the one-electron concepts discussed earlier, including HOMO/LUMO, energy bands, *etc*.

**The "Jacob's Ladder" of KS-DFT**. Different approximations to $E_{\mathrm{xc}}[\rho]$ define the "level of theory" in KS-DFT. Define the xc energy density $\varepsilon_{\mathrm{xc}}[\rho](x)$ as in

$E_{\mathrm{xc}}[\rho] = \int \mathrm{d}x\, \rho(x) \varepsilon_{\mathrm{xc}}[\rho](x)$

There are three classes of "*pure*" DFT methods where $\varepsilon_{\mathrm{xc}}[\rho](x)$ is a local *function* (i.e., not a functional) as in

$E_{\mathrm{xc}}^{\mathrm{pure}}[\rho] = \int \mathrm{d}x\, \rho(x) \varepsilon_{\mathrm{xc}}(x)$

1. **Local density approximation (LDA)**, where $\varepsilon^{\mathrm{LDA}}_{\mathrm{xc}}(x) = \varepsilon_{\mathrm{xc}}(\rho(x))$ depends only on the local electron density $\rho(x)$.

2. **Generalized gradient approximation (GGA)**, where $\varepsilon_{\mathrm{xc}}^{\mathrm{GGA}}(x) = \varepsilon_{\mathrm{xc}}(\rho(x),\nabla\rho(x))$ further depends on the local density gradient $\nabla \rho(x)$.

3. **meta-GGA**, where $\varepsilon_{\mathrm{xc}}^{\mathrm{mGGA}}(x) = \varepsilon_{\mathrm{xc}}(\rho(x),\nabla\rho(x),\tau(x))$ further depends on the kinetic energy density, $\tau(x)$.

<!-- 1. **Local density approximation (LDA)**, where $\varepsilon_{\mathrm{xc}}[\rho]$ is a local *function* (rather than a functional) of the electron density, $\varepsilon_{\mathrm{xc}}^{\mathrm{LDA}}[\rho](x) \equiv \varepsilon_{\mathrm{xc}}(\rho(x))$.

2. **Generalized gradient approximation (GGA)**, where $\varepsilon_{\mathrm{xc}}$ further depends on the density gradient, $\varepsilon_{\mathrm{xc}}^{\mathrm{GGA}}[\rho](x) \equiv \varepsilon_{\mathrm{xc}}(\rho(x),\nabla\rho(x))$.

3. **meta-GGA**, where $\varepsilon_{\mathrm{xc}}$ further depends on the kinetic energy density, $\varepsilon_{\mathrm{xc}}^{\mathrm{mGGA}}[\rho](x) = \varepsilon_{\mathrm{xc}}(\rho(x),\nabla\rho(x),\tau(x))$. -->

There are also "*hybrid*" DFT methods where the xc functional has explicit dependence on orbitals:

4. **Hybrid DFT**, where the exchange part of $E_{\mathrm{xc}}[\rho]$ is a mixture of a pure exchange functional and the HF exchange, which depends on the occupied orbitals, $E_{\mathrm{xc}}^{\mathrm{hyb}}[\{\phi_i\}_{i=1}^{N}] = (1-a) E_{\mathrm{x}}^{\mathrm{pure}}[\rho] + a E_{\mathrm{x}}^{\mathrm{HF}}[\{\phi_i\}_{i=1}^{N}] + E_{\mathrm{c}}^{\mathrm{pure}}[\rho]$.

5. **Double-hybrid DFT**, where the correlation part of $E_{\mathrm{xc}}[\rho]$ is also mixed with the correlation energy from some correlated wavefunction theory, which depends on both the occupied and the virtual orbitals, $E_{\mathrm{xc}}^{\textrm{double-hyb}}[\{\phi_i\}_{i=1}^{K}] = E_{\mathrm{x}}^{\mathrm{hyb}}[\{\phi_i\}_{i=1}^{N}] + (1-b)E_{\mathrm{c}}^{\mathrm{pure}}[\rho] + b E_{\mathrm{c}}^{\mathrm{WFT}}[\{\phi_i\}_{i=1}^{K}]$.

The five approximate classes together form a hierarchy of KS-DFT that is termed [the "Jacob's ladder"](https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1390175) by John Perdew. Higher accuracy is obtained in general as we ascend the ladder, at the price of a higher computational cost. Specifically, pure DFT has a cost scaling of $O(N^3)$, hybrid DFT (comparable to HF) has a scaling of $O(N^4)$, and commonly used double-hybrid DFT, which is based on MP2 or the closely related random-phase approximation (RPA), scales as $O(N^5)$. There are a few hundreds of xc functionals available in the [Libxc](https://www.tddft.org/programs/libxc/functionals/libxc-6.2.2/) library, making a "zoo" of KS-DFT methods. Some widely used xc functionals are **PBE** (a GGA), **B3LYP** (a hybrid GGA), and **M06-2X** (a hybrid meta-GGA), to name a few. Recent developments include self-interaction correction (SIC), range-separated hybrid (RSH), and dispersion correction (e.g., [DFT-D](https://doi.org/10.1063/1.3382344)). A comprehensive benchmark of xc functionals for chemical problems can be found [here](https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/00268976.2017.1333644). Despite hundreds of xc functionals have been developed, none of them is universally accurate across the entire chemical space, motivating a Tiktok-like recommender approach of matching chemical systems and their "best-performing" xc functionals, as will be discussed later in the *Navigating through the zoo of density functional* section.

**Developing an xc functional**. Finally, we give a brief overview on *how xc functionals are developed*. There are two major strategies:

1. The **physics-driven** or **non-empirical** strategy employs functional forms that satisfy known mathematical constraints the exact functional must obey (see [here](https://www.annualreviews.org/doi/full/10.1146/annurev-physchem-062422-013259) for a review). The most famous example is perhaps the **[Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE)](https://journals.aps.org/prl/abstract/10.1103/PhysRevLett.77.3865)** GGA functional, which satisfies 11 constraints. A more recent development is the **strongly-constrained and appropriately-normed (SCAN)** meta-GGA functional, which satisfies all 17 known constraints that a meta-GGA functional can satisfy.

2. The **data-driven** or **semi-empirical** strategy employes a flexible functional form (usually a power series) with undetermined parameters and fits the parameters to accurate reference data, such as CCSD(T) results on small molecules. The most well-known example in this category is perhaps the **Minnesota family**, which consists of nearly 20 highly-parameterized functionals published by the Trular group since 2005. For example, the [MN15](https://pubs.rsc.org/en/content/articlelanding/2016/sc/c6sc00705h) functional has a total of 59 fitted parameters.

The distinction between the two "schools" of functional design is not absolute, and many semi-empirical functionals also include parameters that are determined by satisfying known exact constraints. Indeed, many of the most successful "chemists' xc functionals" are developed this way, including BLYP, B3LYP, and more recently, the "combinatorially optimized" **$\omega$B97X** functional. The data-driven nature also renders ML a natural choice for functional design. A recent example of success in this direction is the deep neural network-based [**DM21**](https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.abj6511) functional developed by DeepMind.

> For readers interested in learning DFT more systematically, we recommend [Burke's website](https://dft.uci.edu/learnDFT.php), which features an introductory textbook titled [The ABC of DFT](https://dft.uci.edu/doc/g1.pdf) and an extensive collection of review articles. This compilation also includes resources on time-dependent DFT for excited states, a topic that we have not covered in this article.

***

**Correlated wavefunction theories**. Different correlated wavefunction theories differ in two ways: (i) how the wavefunction is parameterized (i.e., what the *ansatz* is), and (ii) how the parameters are determined. The former gives rise to different families of correlated wavefunction methods such as configuration interaction (CI), coupled cluster (CC), quantum Monte Carlo (QMC), and many more. The latter determines if a method is variational or perturbative, or is deterministic or stochastic.

**Variational methods: CI, DMRG, and VMC**. The first class of methods we introduce are based on the variational principle that we briefly discussed above. Let $\Psi(\vec{c})$ depend on some parameters $\vec{c}$, which makes the energy a function of these parameters as well

$E(\vec{c}) = \langle\Psi(\vec{c})|H|\Psi(\vec{c})\rangle$

By variational principle, $E(\vec{c}) \geq E_0$ (the true ground-state energy) for all $\vec{c}$, and we can optimize our wavefunction by minimizing its energy

$\vec{c} \gets \min_{\vec{c}} E(\vec{c})$.

All variational methods share the following two computational advantages.

1. The energy is an *upper bound* of the exact ground-state energy, which can often be used as a means to gauge the quality of a wavefunction form.

2. The energy obeys the [*Hellmann-Feynman theorem*](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hellmann%E2%80%93Feynman_theorem), which simplifies the calculation of energy derivatives (e.g., atomic forces).

Different variational methods differ by the specific wavefunction *ansatze* being used.

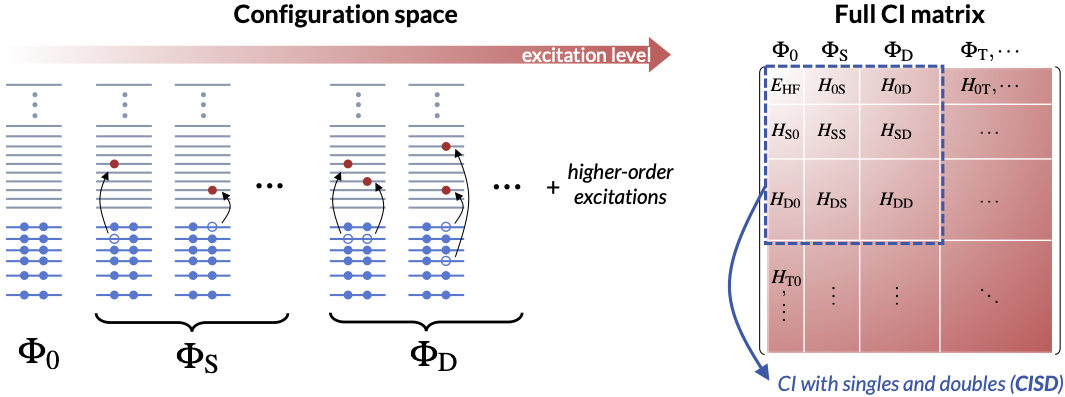

- **Full configuration interaction (FCI)**. Recall that we solve the one-electron Schrödinger equation (and the HF equation) by introducing a set of $K$ basis functions and transforming it into a matrix eigenvalue problem of size $K^2$. The same approach can be applied to solve an $N$-electron Schrödinger equation -- if we can find a proper $N$-electron basis set! A legitimate choice is all $K \choose N$ determinants one can obtain by populating the $K$ HF orbitals with $N$ electrons. The HF determinant $\Phi_0$ has the lowest energy and is called the ground-state *configuration*. Promoting electrons from the HF occupied orbitals to the unoccupied ones leads to excited-state configurations that can be classified as single (S), double (D), triple (T), *etc*. excitations, based on how many electrons are excited from $\Phi_0$. The **full configuration interaction (FCI)** wavefunction is a linear combination of all configurations

$\Psi_{\mathrm{FCI}}

= \sum_{I} c_{I} \Phi_{\mathrm{I}}

= c_0 \Phi_0 + c_{\mathrm{S}} \Phi_{\mathrm{S}} + c_{\mathrm{D}} \Phi_{\mathrm{D}} + c_{\mathrm{T}} \Phi_{\mathrm{T}} + \cdots$

This transforms the $N$-electron Schrödinger equation into a gigantic matrix eigenvalue problem of size ${K \choose N}^2$, solving which results in the *exact* solution to the $N$-electron Schrödinger equation within the chosen one-electron basis set. Since the dimension of the FCI problem $K \choose N$ grows *exponentially* with both $K$ and $N$, we say that FCI has an exponential computational scaling. In practice, FCI is limited to systems with up to 20 electrons, but nonetheless serves as the absolute reference for benchmarking more approximate methods on small molecules.

- **Truncated CI**. Restricting the FCI expansion to a subset of configurations gives the *truncated CI* theory, which is the most straightforward approximation to FCI. For example, a CI with singles and doubles (CISD) wavefunction is

$\Psi_{\mathrm{CISD}}

= \sum_{I} c_{I} \Phi_{\mathrm{I}}

= c_0 \Phi_0 + c_{\mathrm{S}} \Phi_{\mathrm{S}} + c_{\mathrm{D}} \Phi_{\mathrm{D}}$

Following the same logic, there is a hierarchy of truncated CI methods, CISD ($N^6$), CISDT ($N^8$), CISDTQ ($N^{10}$), and so on, which systematically approaches FCI. However, truncated CI is not commonly used in quantum chemistry these days due to its violation of size-consistency, a point that will become clear below when discussing perturbation theory.

<p align="center">

<img width="400" src="https://hackmd.io/_uploads/Skp3zKYbp.png">

</p>

<!--  -->

- **Tensor networks**. An alternative to parameterizing the CI expansion is *tensor networks*, exemplified by the **[density matrix renormalization group](https://arxiv.org/pdf/1407.2040.pdf) (DMRG)** method. The tensor networks theory is motivated by the *[second-quantization](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Second_quantization)* formulation of quantum mechanics, in which the FCI expansion can be written as

$\Psi_{\mathrm{FCI}}

= \sum_{n_1,n_2,\cdots} C_{n_1n_2\cdots} |n_1,n_2,\cdots\rangle$

where $|n_1,n_2,\cdots\rangle$ is a Slater determinant with $n_1$ electron(s) in orbital 1, $n_2$ electron(s) in orbital 2, and so on. Here, the key observation is that the coefficients $C_{n_1n_2\cdots}$ are elements of a *high-dimensional tensor*. Similar to how a matrix can possess a low-rank structure that can be exploited using algorithms such as the [singular value decomposition](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Singular_value_decomposition) (SVD), higher-dimensional tensors can also be broken down into products of tensors with lower dimensions or ranks, which is why they are termed "tensor networks." In particular, DMRG employs a [matrix product state](https://tensornetwork.org/mps/) (MPS) to approximate the coefficient tensor

$C_{n_1n_2n_3\cdots}

\approx \sum_{s_1s_2s_3\cdots}^M A_{n_1}^{s_1} A_{n_2}^{s_1s_2} A_{n_3}^{s_2s_3} \cdots$

where the $\mathbf{A}$ tensors are variational parameters. The DMRG wavefunction can be progressively improved to approach FCI by increasing the "bond dimension", $M$, which controls the rank of the product tensor. The cost scaling of DMRG is $O(N^4)$ but the prefactor grows with bond dimension as $O(M^3)$. Recent implementations have demonstrated the ability to attain FCI-level accuracy for about 80 electrons (see e.g., a recent preprint from [the Chan group](https://arxiv.org/abs/2310.03920)). Methods like DMRG thus significantly expand the scope for FCI-like methods.

- **Variational Monte Carlo (VMC)**. A major difficulty preventing one from using an arbitrary wavefunction *ansatz* in variational optimization is the high computational cost associated with evaluating the energy (and its gradients), which, when written explicitly, is a multi-dimensional integral explicitly

$E[\Psi]

= \frac{\int \mathrm{d} X |\Psi(X)|^2 H(X)}

{\int \mathrm{d} X |\Psi(X)|^2}$

*Varitional Monte Carlo (VMC)* bypasses this curse of dimensionality by using Monte Carlo sampling to stochastically evaluate the needed integrals. As a result, VMC enables using some wavefunction forms that are otherwise inaccessible to direct variational optimization. A commonly used one is the *Slater-Jastrow ansatz*

$\Psi_{\mathrm{SJ}}(X)

= \Phi_0(X) \exp\left[ \sum_{i < j} u_{ij}(x_i,x_j) \right]$

where the Jastrow correlation factor $u_{ij}$, being the variational degrees of freedom, explicitly encodes the correlation effect between two electrons. One disadvantage of VMC (and any other stochastic methods) is the inherent statistical error, which can complicate the evaluation of atomic forces and other properties.

***

**Perturbation methods: MBPT and CC**. While giving an energy upper bound by variational methods seems an appealing property, in practice what is often more important is **size-consistency**. A method is size-consistent if it predicts the energy of two non-interacting molecules to be the same as the sum of the energies of the two individual molecules, i.e., $E(A+B) = E(A) + E(B)$. Methods violating size-consistency introduce bias based on system size, resulting in poor performance for e.g., reaction energy calculations. A closely related concept for condensed-phase materials is **size-extensiveness**. A method is size-extensive if the energy scales *linearly* with system size in the bulk limit, i.e., $E(N) \propto N$ for $N \to \infty$. Unfortunately, most variational methods are neither size-consistent nor size-extensive, rendering them unsuitable for simulating chemical reactions or condensed-phase systems in general. An important exception is FCI, which is both variational and size-consistent/extensive for the trivial reason that FCI being the exact solution. Consequently, variational methods are mostly used for generating highly accurate reference results for small molecules (or small [active space](https://chemistry.stackexchange.com/questions/64483/what-are-complete-active-space-methods-and-how-are-such-spaces-defined-for-molec) in CAS methods) where one can reliably approach the FCI limit.

The above discussion motivates the introduction of many-body perturbation theory (MBPT) and coupled cluster (CC) theory, both of which are rigorously size-consistent and size-extensive and hence more applicable to large systems.

- **Many-body perturbation theory (MBPT)**. For systems where electron correlation is not strong, the HF ground state $\Phi_0$ dominates the FCI expansion with $c_0 \sim 1$. The remaining CI coefficients, being small in magnitude, can be determined in a *perturbative* manner. Mathematically, this is done by separating the Hamiltonian into two parts, $H = F + V$, where the eigen spectrum of the Fock operator $F$ is already known ($\Phi_0, \Phi_{\mathrm{S}}, \Phi_{\mathrm{D}}, \cdots$). The wavefunction and energy are then expanded as power series of the "fluctuation potential" $V$ and can be solved for *order by order*. The leading order correction to the HF energy comes from double excitations and is at second order, resulting in the **MP2** theory (named after its two original developers, [Møller and Plesset](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/M%C3%B8ller%E2%80%93Plesset_perturbation_theory)). MP2 has been widely used in molecules and more recently in materials for its size-consistency/extensiveness and, perhaps more important, it being the cheapest correlated theories, with a modest $O(N^5)$ computational scaling. MP2 is the first member of the MP$n$ series, followed by MP3 ($N^6$ cost), MP4 ($N^7$ cost), and so on that include triple excitations and higher-order effects. However, these higher-order perturbation theories are not as commonly used as MP2 due to their slow convergence to FCI or, in some cases, divergence. Additionally, MP3 and higher-order methods share similar cost scalings with more powerful theories like coupled cluster, which we will introduce now.

- **Coupled cluster (CC)**. The CC wavefunction takes an exponential form

$\Psi_{\mathrm{CC}}

= \mathrm{e}^{T} \Phi_0

= \left( 1 + T + \frac{1}{2}T^2 + \cdots \right) \Phi_0$

where $T = T_1 + T_2 + \cdots$ generate single, double, *etc*. excitations from $\Phi_0$. It can be shown that when $T$ is untruncated, the full CC wavefunction is equivalent to FCI and hence exact. In practice, $T$ is truncated to include only low-level excitations just like truncated CI. For example, $T = T_1 + T_2$ gives **coupled cluster with singles and doubles (CCSD)**. The cost scaling of CCSD is $O(N^6)$ and equivalent to MP3 and CISD. However, CCSD has two key advantages that make it the most widely used $O(N^6)$-scaling method.

1. CCSD iteratively determines coefficients for the single ($T_1$) and double ($T_2$) excitations, encompassing their contributions to an *infinite* order. This is similar to CISD but much better than MP3, which is only correct up to the second order in double excitations (*cf*. MP2 is first order in double excitations).

2. The exponential form of the wavefunction generates *products* of excitations that correspond to *disconnected* higher-order excitations. For example, the simultaneous excitation of two distant electron pairs is important for electron correlation in large molecules or materials, but being a (disconnected) quadruple excitation means that it requires at least MP4 ($\geq N^7$ cost) or CISDTQ ($\geq N^8$ cost). By contrast, CCSD naturally includes this excitation type through the $T_2^2$ term generated by expanding the exponential, as well as many more disconnected higher-order terms such as $T_1 T_2$, $T_1^2 T_2$, $T_1 T_2^2$, *etc*.

\

*[The indentation here is still not correct. Ideally it should be aligned with the bullet point "**• Coupled cluster (CC)**".]* For many chemistry problems where electron correlation is weak, CCSD can be further improved by *perturbatively* including the triple excitations, leading to one of the most successful correlated wavefunction theories in quantum chemistry, **coupled cluster with singles, doubles, and perturbative triples [CCSD(T)]**. CCSD(T) consistently delivers chemical accuracy for weakly correlated problems and is often dubbed the **quantum chemistry "gold standard"**. The $O(N^7)$ cost scaling of CCSD(T) limits its application to small molecules of approximately 10 atoms, but various *linear-scaling* techniques, exemplified by the *domain local pair natural orbitals (DLPNO)* and *local natural orbitals (LNO)* approximation, have significantly expanded the scope of CCSD(T) to systems with up to 100 atoms. For example, in [a recent work](https://arxiv.org/abs/2309.14640), Ye and Berkelbach employed a periodic implementation of LNO-CCSD(T) to study water dissociation on TiO2 surfaces.

> For readers eager to learn MBPT and the CC theory systematically, especially the powerful diagrammatic tools that simplify the derivation of seemingly complex algebraic expressions, we recommend the textbook by Shavitt and Bartlett, titled *[Many-Body Methods in Chemistry and Physics: MBPT and Coupled-Cluster Theory](https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/manybody-methods-in-chemistry-and-physics/D12027E4DAF75CE8214671D842C6B80C)*.

### Topics not covered here

The above only serves as an outline for a subset of quantum chemistry methods. Here's a list of other developments you may find interesting.

- **Strongly correlated systems**. The correlated wavefunction theories we've discussed are primarily categorized as "**single-reference**" methods, which operate under the assumption $c_0 \approx 1$ in the FCI expansion, implying that HF already offers a reasonable starting point. Systems satisfying this criterion are often referred to as **weakly correlated**. This includes most closed-shell systems (which lack unpaired electrons) with a sizeable HOMO-LUMO/band gap. Classical examples include many organic molecules and simple insulating solids. On the other hand, **strongly correlated** systems are those where multiple configurations contribute significantly to the FCI wavefunction, meaning that $c_0 \ll 1$. Such systems typically require **multi-reference** methods for an accurate description. Many single-reference methods have corresponding multi-reference extensions, such as *complete active space self-consistent field (CASSCF)*, *CAS perturbation theory to the second-order (CASPT2)*, *multi-reference configuration interaction (MRCI)*, among others. Strongly correlated systems are often characterized by the presence of unpaired electrons, found in radical molecules and magnetic materials, or by a small energy gap. In this context, DFT behaves more like a mean-field approximation and often fails catastrophically when applied to strongly correlated systems.

- **Excited states**. The discussion above is limited to the electronic ground states. Excited states, being higher-energy solutions to the Schrödinger equation, are crucial for understanding photochemistry and many physical processes in solids, such as excitons and plasmons. Two primary strategies exist for expanding a ground-state theory to simulate excited states. The *direct* approach involves directly seeking higher-energy solutions to the Schrödinger equation within the same approximation as the ground-state theory. The *response* approach, on the other hand, describes excited states as the response of the ground state to a time-dependent perturbation. Examples of the former category include ΔSCF (*aka* [orbital-optimized DFT](https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.jpclett.1c00744) within the KS-DFT framework), state-specific/average CASSCF, while examples of the latter include time-dependent DFT (TDDFT), equation of motion CC (EOM-CC), among others. For an introductory review on excited-state methods, we recommend a 2005 Chemical Review article by [Dreuw and Head-Gordon](https://doi.org/10.1021/cr0505627).

<!-- ### Opportunities for ML x Quantum chemistry -->

<!-- ML part for Chenru to draft -->

## Recent advances with ML in quantum chemistry

### Bypassing the need to solve the Schrödinger equation

It has been a while [since 2013](https://journals.aps.org/prl/abstract/10.1103/PhysRevLett.108.058301) that people use machine learning (ML) to predict chemical properties of molecules or the energy and forces for [molecular dynamics](https://ai4science101.github.io/blogs/molecular_simulation/), but these ML model do not really learn the foundamental electronic structures of the molecules and materials from a perspective of solving the Schrödinger equation and alike. However, there has been a recent surge of development where ML is directly baked in quantum chemistry, such as predicting the electron density, Hamiltonian matrix, and wavefunctions. These models have become increasingly accurate with the widespread of equivariant neural networks, which preserve all the symmetries required for these tensorial foundamental quantum chemistry properties (e.g., [e3nn](https://github.com/e3nn/e3nn)).

*Predicting electron density.-* Electron density is a fundamental variable in density functional theory (DFT), from which, in principle, all ground state properties can be derived. Therefore, it is the "to-go" target for chemistry and materials system beyond energy and forces. Well ahead of the rise of equivariant models, [Grisafi et al.](https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acscentsci.8b00551) built a symmetry-adapted Gaussian process regression (SA-GPR) model to matain the correct symmetries that an ML model needs for electron density prediction. They found that, trained on short alkanes (CH4, C2H6, C3H8, ...), SA-GPR can readily generalize to larger alkanes of different conformations. Besides enforcing the ML model to have the correct symmetry, many attemped to encode the symmetry in the molecular representation. For example, [Achar et al.](https://www.mdpi.com/2079-4991/13/12/1853) used Smooth Overlap of Atomic Positions ([SOAP]( https://singroup.github.io/dscribe/0.3.x/tutorials/soap.html#:~:text=Smooth%20Overlap%20of%20Atomic%20Positions%20(SOAP)%20is%20a%20descriptor%20that,harmonics%20and%20radial%20basis%20functions.)) as representation to learn the electron density for both molecular and materials systems. More recently, people have adapted [density fitting](https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-020-20471-y), a conventional quantum chemistry approach to partition the total electron density to the single-atom basis,

$\rho(r) = \sum_{\mu, \nu} D_{\mu \nu} \chi_\mu(r) \chi_\nu(r) = \sum_{A,Q} C_A^Q \phi_Q(r-r_A) = \sum_A \rho_A(r)$

which projects the original basis functions based electron density (with density matrix $D_{\mu \nu}$) to atom-centered auxilliary basis ($C_A^Q$). Therefore, with equivariant neural networks, [we can directly learn these decomposed tensors](https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/2632-2153/acb314) from electron density, boosting both the model accuracy and transferability.

*Predicting Hamiltonian matrix.-* The goal of SCF calculations in DFT (or HF) is to obtain the converged Hamiltonian matrix as the solution of $H_{DFT} \Psi = E \Psi$ in the non-interacting basis representation. Then almost all electron-related physical quantities in the single-particle picture can be derived, such as charge density, band structure, and physical responses to electromagnetic fields. Compared to electron density, $H_{DFT}$ is practically more straightforward to derive these property. However, $H_{DFT}$ is at the size of $N^2$, where $N$ is the number of basis function, which is too large to learn. Luckily, one can ultilize the principle of locality in normal chemical system (this assumption breaks down for "quantum matter" that has very strong correlation). Thus, there is no need to study the entire $H_{DFT}$, but only its sparsed approximation, which then reduce the scaling to O(N). Combined with equivariant model architecture, [Li et al.](https://www.nature.com/articles/s43588-022-00265-6) showed that they can learn the Hamiltonian quite accurately, even to a degree that unveils the band structure of bilayer twisted graphene.

### Neural network as a functional approximator

Many complication in quantum chemistry boils down to the high-dimentional mapping between a system of study to its electronic structure properties, such as electron density and wavefunction. Therefore, a school of thought is to approximate this underlying mapping when we construct the solution.

*Neural network as a density functional.-* The Kohn–Sham (KS) DFT, in which only the exchange-correlation (xc) energy needs to be approximated as a functional of the density, has greatly improved accuracy while "only" scales to $O(N^3)$. Due to the approximation in xc functional, there would be errors that are somewhat unpredictable during its application. Once the exact xc was found, however, all ground-state properties would be solved in agreement with FCI at a $O(N^3)$ cost, which is the dream of quantum chemistry. ML has already helped with functional development. Almost 20 years ago, using [Bayesian inference]((https://journals.aps.org/prb/abstract/10.1103/PhysRevB.85.235149)), a new DFA can be assembled as a linear combination of functional forms with statistically inferred coefficients, accelerating DFA design using known functional forms and alleviating the risk of overfitting during DFA parameterization. ANNs have been used as an ansatz for designing DFAs due to their ability to represent any function. [Brockherde et al.](https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-017-00839-3) developed ML models that directly learn the ground-state density of a system, reducing the computational cost of solving the Kohn–Sham (KS) DFT equations iteratively. By incorporating the KS equations as a regularization term in the loss function and providing feedback to ANNs in each training iteration, [Nagai et al.]((https://www.nature.com/articles/s41524-020-0310-0)) and [Li et al.](https://journals.aps.org/prl/abstract/10.1103/PhysRevLett.126.036401) demonstrated that the ANN functional can be learned with very few training molecules. [Kasim et al.](https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-020-19093-1) recast KS-DFT in a fully differentiable framework, enabling a density functional expressed as an ANN to be optimized with backpropagation, which demonstrated transferability to other small molecules containing elements and bond types not in the training set. Again, with the widespread of open-source packages for equivariant neural networks, people have recently shifted towards including symmetries and exact constraints of the exact xc during learing density functional, with a prominent example as [DM21](https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.abj6511), where the piece-wise linearilty and flat-plane condition were explicitly considered.

*Neural network as ansatz in quantum Monte Carlo (QMC).-* As a variantional approach, QMC has the great property that for whatever guess wavefunction, the resulting electronic energy will always smaller or equal (if the guess is the true wavefunction) to the ground state energy. Therefore, by [modeling wave functions as NNs](https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.aag2302) and using the resulting energy expectation as the loss function, one can employ self-consistently sampling from the square of the wave function with QMC and generates its own data on the fly. This approach has been applied to spin systems on lattices and Hubbard model. By modifying the ansatz to include anti-symmetry constraints, [Hermann et al.](https://www.nature.com/articles/s41557-020-0544-y) parameterized a multi-determinant Slater-Jastrow-backflow type wavefunction with NN. By applying the variational principle on this ANN wavefunction ansatz, they showed that the correlation energy can be quickly recovered (ca. 99%) for most of their test systems using very few (i.e., 10) determinants. To date most approaches have only been demonstrated on small systems with paired electrons, where MR WFT calculations can be performed easily. It is imperative to extend these developments to large systems with challenging electronic structure (e.g., metal–organic bonding) in order to impact ML-accelerated discovery of novel materials.

### Integrating ML models in high throughput computation

With the advancement of cloud infrastructure and workflow automation, high throughput computation (HTC), where thousands of jobs are simutaneously run under workflow management instead of one, has been a common tool to generate large databsets for chemical and materials discovery. Despite there are so many quantum chemistry methods out in the market, DFT remains the most accurate method among all that are practical (e.g., force field, semi-emperical) in HTC. However, the accuracy of DFT depends on the choice of density functional. That is where ML can help.

*Addressing DFT sensitivity.-* Density functionals are conventionally selected based on intuition or computational cost, thus introducing bias in data generation and reducing the quality of the data in a way that degrades utility for discovery efforts. To address this challenge, [McAnanama-Brereton and Waller](https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.jcim.7b00542) developed an approach to identify optimal DFA-basis set combinations using game theory. They devised a three-player game addressing accuracy, complexity, and similarity of DFA-basis set combinations and solved the Nash equilibrium to yield the optimal combination. Alternatively, [Duan et al.](https://pubs.rsc.org/en/content/articlelanding/2021/SC/D1SC03701C) treated different density functionals as multiple experts, who can sometimes give contradicting suggestions. By requiring consensus among predictions of more than half of the density functionals, they overcame the limitation of the single-functional approach in HTC, producing robust candidate materials in agreement with experiment.

*Navigating through the zoo of density functional.-* The consensus approach mentioned above, though practically useful, would loose the strength of quantum chemistry, where multiple properties can be derived at once (e.g., with electron density). Inspired by modern scheme of recommendation in Spotify and Tiktok, Duan et al. recently developed a [density functional recommender](https://www.nature.com/articles/s43588-022-00384-0), which is native to the current HTC. For every single systems, this density functional recommender recommends a functional that is expected to yield the lowest error compared to the reference (e.g., experiment). Their recommender approach yields a mean absolute error of 2.1 kcal/mol, outperforming the use of any single functional in the HTC for discovering spin-crossover compounds, which are particularly sensitive to the choise of functional. Due to the use of electron density as underlying representation for their models, the recommender is transferable to out-of-distribution experimental data and molecules of completely different coordination chemistry.

## Outlook

Quantum chemistry lies in the core of how people understand chemical reactions, which forms the world in which we live. Most of the pain in quantum chemistry can be attributed to the curse of dimensionality, where ML has proven to be useful to address. ML integration in quantum chemistry is a young, yet rising direction, with the potential to uncover the understanding to more complicated and large-scale chemical behavior that are both difficult to simulate in cloud and wet lab. It is an interdisciplinary field that welcomes knowledge and contribution from chemistry, physics, computer science, applied math, and more. It also welcomes you.

Sign in with Wallet

Sign in with Wallet