---

tags: seminar

---

# Extended guide licensing and copyrigt at TU Delft

## Introduction

An important aspect of research software reusability is to give consent to third parties about how the software can be built, modified, used, accessed and distributed. Even if a code repository is made open, this is not equivalent to giving consent to use it. The consent is given by providing a software license.

When possible, TU Delft (TUD) encourages its researchers to make their software available Open Source, in the spirit of our Open Science movement. Yet, when making software available to others there should be a balance between the possible commercial exploitation of software and the benefit of open source. At TU Delft, software is recognised as a valuable research output. Therefore, software should be well documented, preserved and, whenever possible, consistent with the FAIR principles (should be well-managed the same as research data). Research institutions recently started to publish Research Software policies and Guidelines towards increasing the value of research software assets worldwide ([https://www.researchsoft.org/software-policies/](https://www.researchsoft.org/software-policies/)). The TU Delft Research Software Policy provides a simplified and streamlined process and workflow to help researchers share software.

:::info

**Useful TUD resources:**

- TU Delft Research Software Policy: https://zenodo.org/record/4629662

- TU Delft Guidelines on Research Software: Licensing, Registration and Commercialisation: https://zenodo.org/record/4629662

:::

This tutorial gives an overview of the different kinds of Open Source licenses typically used to share and collaboratively develop software to make it easier for you to properly license the software you create for your research project.

<!-- ## Definitions

- **Research software**: https://zenodo.org/records/5504016

- **Derivate software**: Your code is derivative work if you have started from an existing code and made changes to it or if you incorporated an existing code into your code. If the original code does not have a license, you may not be able to distribute your derivative code. You can try to contact the authors and ask them to clarify the license of their code.

- **Non-derivative software**: If you have started “from scratch” a project, and not used any existing code, or incorporated existing code into your code, then you may consider your code to be not derivative work.

:::info

Further information about License compatibility and its feature on derivate and non-derivative software can be found in [https://the-turing-way.netlify.app/reproducible-research/licensing/licensing-compatibility](https://the-turing-way.netlify.app/reproducible-research/licensing/licensing-compatibility).

:::

- **License**: provides legally binding guidelines and requirements for the use and distribution of the software. Licences typically provide end users with the right to one or more copies of the software without violating copyright law. Open source licences typically grant this right to all of humankind rather than to a specified end-user. -->

## Why licensing your research software is important?

Before starting to discuss the different paths to share your research software, it is very relevant to keep in mind that creation of software is protected under copyright law (see pag.16 [TU Delft Policy](https://zenodo.org/records/4629635)).

::: success

**Why is important?**

* Based on the law, TU Delft owns the software that is written by employees.

* When copyright exists, others (i.e. general public or a commercial entity) are not free to reproduce, copy, adapt, amend, distribute, perform, display or make the software public without the explicit permission of the owner of that copyright.

:::

In contrast to other types of intellectual property (like patents, trademarks or design rights), there is no registration of a copyright needed to claim the creator’s right of software. Even when an explicit notification is absent in a program, the copyright exists and infringement of the copyright occurs when using the software without explicit authorisation of the creator. Therefore:

- If software developers, researchers and staff creating software want to make their software available for free, the permission of this intention must be clearly indicated to the public by using an appropriate open source software licence (OSS).

- In order for the software developers, researchers and staff to use an OSS licence TU Delft is willing to waive its claim to the copyright provided the procedure described in these guidelines is followed. Note that in this case the software developer or researcher establishes an own copyright: ***e.g. © (2024) John Doe, Delft, the Netherlands***.

- When a proprietary software licence is intended and in all other cases, software developers, researchers and staff should assert copyright on behalf of TU Delft. This can be done by using the copyright symbol, followed by a date and an identifier: e.g. © (2024) Technische Universiteit Delft.

Like a research software license, a other digital objects has license that governs what someone else can do with for instance, data that you create or own and that you make accessible to others through,a data repository. Licenses vary based on different criteria, such as:

- [Hardware](https://the-turing-way.netlify.app/reproducible-research/licensing/licensing-hardware)

- [Data](https://the-turing-way.netlify.app/reproducible-research/licensing/licensing-data)

- [Machine Learning Model](https://the-turing-way.netlify.app/reproducible-research/licensing/licensing-ml)

:::success

**💡 Extra:** To learn more about how to add a license to other research digital objects, read the [Licensing chapter](https://the-turing-way.netlify.app/reproducible-research/licensing.html) in The **Turing way Guide** for Reproducible Research.

:::

## What are the types of license for research software?

Fundamentally there are two kinds of licence within the software community, **Open Source licences** and **Proprietary licences**, which serve slightly different purposes, but both are established as community standards:

- **Free and Open Source licences** Open-source licenses are legal agreements that govern open-source software’s use, modification, and distribution and outline the terms and conditions under which developers and users can access and utilize the source code of a software project. Their primary objective is to promote collaboration, transparency, and the free sharing of knowledge within the software development community. The various types of open-source licenses each have their own set of conditions, requirements, permissions, restrictions, and obligations. Within the open source licences, there are two categories, *copyleft* and *permissive*:

- The *permissive licences* such as MIT or Apache, and the multiple variants of the BSD licence are designed to give maximum freedom to the end users of software. These licences allow the end user to do almost anything with the source code.

- *The copyleft licences* in the GPL still give a lot of freedom to the end users, but any code that they write based on GPLed code must also be licensed under the same licence. This gives the developer assurance that anyone building on their code is also contributing back to the community. It’s actually a little more complicated than this, and the variants all have slightly different conditions and applicability, but this is the core of the licence. Copyleft licenses, such as the GNU General Public License (GPL), impose certain restrictions on how the software can be used and distributed

<!--  -->

- **Proprietary licences** are designed to pass on limited rights to reusers, and are most suitable if you want to commercialise your research software. They tend to be customised to suit the requirements of the software and the institution to which it belongs - again your institutions IP team will be able to help here (please closely inspect the TU Delft Research Software Policy to check further guidelines on proprietary licensing[https://zenodo.org/records/4629662](https://zenodo.org/records/4629662)).

The table below summarizes the main types of software licenses:

Which of these types of licence you prefer is up to you and those you develop code with. If you want more information, or help choosing a licence:

- Use the Creative Common license tool to decide which license to use:

- https://chooser-beta.creativecommons.org

- https://choosealicense.com/

- https://tldrlegal.com/

:::warning

## **Exercise 1: Exploring the standards in your community**:

Search on GitHub or other software repositories for software created by researchers at your institute and/or any group that belongs to your scientific community. What licenses do they tend to use? Do they adhere to a policy (if there is one?)? is there any widely-used community standards that faciliate the choice of a license type?

---

<!-- :::success

**💡 Extra:** Search on GitHub or other software repositories for software created by researchers at your university. What licenses do they use? Do they adhere to a policy (if there is one?)

::: -->

:::

## How to chose a license for your project: the key factors to consider

Choose a license early in the project, even before you publish it is a must. Otherwise it may become complicated to change or modify the licensing after the project is finished. Agreeing on a software license does not mean that you have to make it open immediately. Selecting the right open-source license (or not!) for your project is a crucial decision that can impact its success, community engagement, and most importantly, the legal compliance. Before you may choose a license, clarify the following points with, for example, your supervisor, collaborators, principal investigator, or any stakeholder of interest:

1. **Alignment with project objectives**: Does the selected license support your primary goals for releasing the software?

2. **Alignment with stakeholders**: Does your work contract, grant, or collaboration agreement dictate a specific license such proprietary types?

3. **Dependency compatibility**: Are all required third-party libraries and tools licensed compatibly?

4. **Community impact**: How easy is it for potential reusers to incorporate your software into their projects?

5. **Community standards**: Which license is widely adopted within your research community?

6. **Legal guidance**: Seek professional advice if needed to fully comprehend the implications of your chosen license.

<!--

## How to add a license if your work is derivative work? -->

---

:::warning

## **Exercise 2: Identyfing your license type based on TU Delft Policy**:

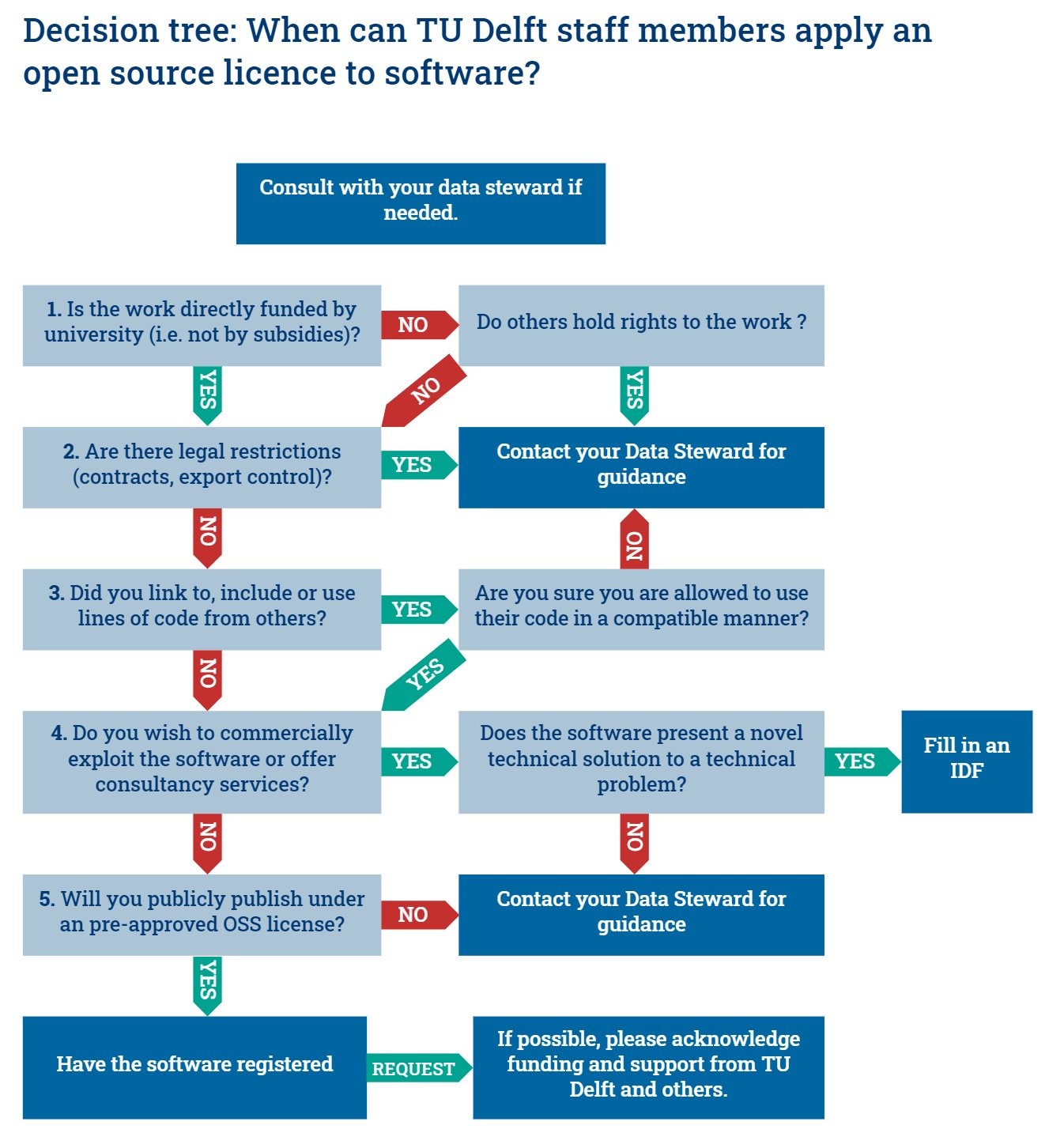

The TUD Policy also mentioned same factors to be considered before selecting your license, and could be summarised in the following decision-tree diagram:

Having identified the essential properties for licenses and the core factors to be considered when applying an open source lincense, now its time to make a decision for your project. Consider the impact of each term on potential rusers and determine which license would be most suitable for your project considering factors like we discussed above.

Try to find out whether TUD has a clear workflow on how to determine whether OSS license can be applied to a software. What does it say about which license(s) to use? If your scenario is not covered, which further considerations are needed to license(s) would you choose for your policy? Why?

<!--  -->

:::

<!--

:::info

**Learning Objectives**

By the end of this tutorial, you will be able to:

1. Understand why using an open source license is beneficial for research software

2. Recognize common open source licenses and their main differences

3. Choose the best open source license for your specific research software project

**What to expect**

By the end of the tutorial we would like you to have a documentation approach/system that fits your project requirements.

:::

## 📆 Instructions

1. **Introduction to Open Source Licensing for Research Software**

* Brief overview of open source licensing

* Importance of open source licensing for research software

2. **Popular Open Source Licenses:**

* Exercise 1: Identifying key components of popular licenses (MIT, Apache, GPL)

* Exercise 2: Comparing terms and conditions

3. **Choosing the Right License for Your Project:**

* Factors to consider

* Exercise 3: Making informed decisions based on project needs

* Exercise 4: Choose a license for or using your policy -->

<!-- ## 🙋 Discussion and questions

- Reflect on the fact that preparing a repo to become reproducible is already a documentation exercise.

- You have already started working on dependency documentation and installation instructions.

- Some have tests and notebook examples.

- Readable code is documentation.

:::warning

**Some statements to provoke discussion:**

- Documentation is everything

- *What do you think is the main documentation source in a codebase?*

- Code is for computer, comments are for humans.

- *What is the role of comments in your code?*

- Readable code is sufficient for good code documentation.

- *Who should be reading your code?*

- Different users approach your code differently.

- *Can you think of different users and usecases?*

- *Which documentation tools would you use?*

::: -->

<!-- 👉 Go to [**collaborative document**](https://hackmd.io/@fair4rs/rJoEhe4zn). -->

<!--

---

### 1. Introduction to Open Source Licensing for Research Software

Free, Open Source Software (or FOSS, as it's sometimes abbreviated) is software that you are free to 0) use for any purpose, 1) modify to suit your needs, 2) share with others, and 3) share with changes you made, so you can work on it together. That's actually the Free Software definition, but Open Source really just says the same thing in more words, which is why they're usually mentioned together. These are exactly the permissions scientists need to be able to do science together using the software.

Open Source licenses also allow commercial use, which means that they are a very effective means of technology transfer. Since the license terms are the same for everyone, there are no issues with state aid regulations, nor does a market-rate value for the software need to be determined. The standard Open Source licenses are now well understood and trusted by commercial parties, removing the need for complex negotiations on the exact terms. Of course, no payment will be received either. Given that commercial sale of academic software is very rare, it seems that the benefits obtained from the academic collaboration enabled by Open Source far outweigh the potential income loss due to not commercially licensing the software. And note that it is still perfectly possible to launch a spin-off or start-up that offers commercial services related to the software, including support and continued development.

Open source licensing allows developers to share their creations with the wider community while maintaining control over their intellectual property. For research software, there are several compelling reasons to adopt an open source approach:

:::warning

* Encourages collaboration and knowledge exchange among peers

* Promotes transparency and reproducibility

* Facilitates rapid innovation and improvement

* Reduces costs associated with proprietary solutions

:::

---

-->

<!--

<!--

:::success

**💡 Tip:** Licenses simplified by [Choose a license](https://choosealicense.com/licenses/) and [Software licenses in plain English](https://www.tldrlegal.com/)

:::

Take careful notes on the following aspects:

* Granted permissions to users

* Conditions for distribution

* Required attributions

:::info

For more information, detailed [TU Delft Research Software Guidelines](https://d2k0ddhflgrk1i.cloudfront.net/TUDelft/Over_TU_Delft/Strategie/TU%20Delft%20Research%20Software%20Guidelines.pdf) about licensing, registration, and commercialization are available. This document also details the required steps to reclaim the copyright to your software (page 27) as TU Delft by default holds the rights to the software created by its employees.

:::

-->

---

## Instructions to add license in Github:

Regardless of derivative or non-derivative work, the following section is about the practical steps for adding a license to your project repository. Based on the [FAIR-CODE](https://github.com/manuGil/fair-code/tree/main):

**1. Go to your repository folder (local computer or online repository on GitHub/GitLab/BitBucket)**

<!-- 2. Create a new file and name is `License.txt` or `License.md` based on your preference of the file format -->

**2. Choose a type of license** (or multiple license for mixed content) that is suitable for your project. If no licensing is stated, the default of "no license" is "no one can make copies or derivative works of your code".

Under the current [guidelines on research software](https://d2k0ddhflgrk1i.cloudfront.net/TUDelft/Over_TU_Delft/Strategie/TU%20Delft%20Research%20Software%20Guidelines.pdf), TU Delft encourages the use of open source licenses for research software. Use the decision three below to determine if the software you intend to develop can be published as Open Source Software (OSS). You can also ask for help to the [Data Steward in your Faculty](https://www.tudelft.nl/library/research-data-management/r/support/data-stewardship/contact)

**3. If using an open source license,** select one of the followings **pre-approved** licences:

| License | Link |

|---------|------------|

| CC0-1.0 | [](http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) |

| MIT | [](https://opensource.org/licenses/MIT)|

| BSD-3 | [](https://opensource.org/licenses/BSD-3-Clause) |

| Apache-2.0 | [](https://opensource.org/licenses/Apache-2.0) |

| EUPL-1.2 | [EUPL-1.2](https://opensource.org/licenses/EUPL-1.2) |

| GPLv2 | [](https://www.gnu.org/licenses/old-licenses/gpl-2.0.en.html) |

| GPLv3 | [](https://www.gnu.org/licenses/gpl-3.0) |

| LGPLv3 | [](https://www.gnu.org/licenses/lgpl-3.0) |

**4. If an OSS license will be used, create a new file and name is** `License.txt` or `License.md` based on your preference of the file format. Edit the `LICENSE` file to match your case.

:::warning

## **Exercise 3: Licensing your research software project**:

Your task is to add a license file to your repository based on the above steps. Use the following links to further explore details:

- Check the FAIR CODE template: https://github.com/manuGil/fair-code/tree/main

- Check the GitHub documentation to know how to add a license file. Use this tool to generate a CITATION file and add it to your repository: https://citation-file-format.github.io/cff-initializer-javascript/#/

- Check the Checklist Turing Way: https://the-turing-way.netlify.app/reproducible-research/licensing/licensing-checklist#checklist

:::

<!-- ## Assignments for Wednesday 26th of April

The goal of the this week's challenges and assignments is to find a documentation system/approach that works for your project specific needs.

:::success

**💡 Tip:** Add the FAIR cards to your github board to as a reference for FAIR documentation.

::: -->

<!-- ### FAIR card - Project documentation

```markdown

_Essential_

- [ ] [README](https://github.com/18F/open-source-guide/blob/18f-pages/pages/making-readmes-readable.md)

- [ ] [LICENSE](https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4629662)

- [ ] [CITATION](https://docs.github.com/en/repositories/managing-your-repositorys-settings-and-features/customizing-your-repository/about-citation-files)

_Recommended_

- [ ] Make use of [Github issues](https://docs.github.com/en/issues/tracking-your-work-with-issues/about-issues)

- [ ] [Code of conduct](https://docs.github.com/en/communities/setting-up-your-project-for-healthy-contributions/adding-a-code-of-conduct-to-your-project)

```

### FAIR card - Software documentation

```markdown

_Essential_

- [ ] Installation instructions

- [ ] User documentation

- [ ] Developer documentation

- [ ] Source code documentation ([docstrings](https://numpydoc.readthedocs.io/en/latest/format.html))

_Recommended_

- [ ] Examples and tutorials (Jupyter notebooks, videos, screencasts)

- [ ] Automate documentation building with [sphinx](https://coderefinery.github.io/sphinx-lesson/)

- [ ] Website ([github.io pages](https://pages.github.com/), [Readthedocs](https://readthedocs.org/), [JupyterBook](https://jupyterbook.org/intro.html)

_Optional_

- [ ] Build [API reference](https://developer.lsst.io/python/numpydoc.html) from docstrings

``` -->

<!--

2. CITATION.cff file

You can add a [CITATION.cff](https://citation-file-format.github.io/) file to the root of a repository to let others know how you would like them to cite your work. The citation file format is plain text with human- and machine-readable citation information. More information and compatible tools can be found in this [repository](https://github.com/citation-file-format/citation-file-format).

### Assignment 2

Now that we have the minimum required for FAIR documentation for research software, let's define a broader approach towards your project documentation.

:::info

**What do we mean by documentation system?**

What no body tells you about documentation is that is not just one thing, but several. How-to-guides, tutorials, in-code documentation, knowledge-base and explanation of concepts can all be part of documentation. In the case of research software, Jupyter notebooks often are an essential documentation tool. [**Divio**](https://documentation.divio.com/) offers a great overview of the types of documentation.

:::

1. Define the documentation that you, your users, and your collaborators would need to understand and use your software.

2. Make a todo list (GitHub issues) based on these considerations.

:::success

**💡 Tip:** Think about a minimum approach that improves your current situation, and a more ambitious approach.

:::

### Assignment 3

[Readable code](https://raw.githack.com/mwakok/FAIR4RS/main/Readability.html) and [in-code documentation](https://coderefinery.github.io/documentation/in-code-documentation/) are important parts in making your code easy to understand To improve the readability of your code, you should consider:

- Writing code comments that explain the **why** of the code and not the **what**.

- Adding docstrings to (public) functions.

- Using common naming conventions (check a style guide).

- Adding whitelines and avoid compound statements.

:::info

Every major open-source project (e.g. [**Numpy**](https://numpydoc.readthedocs.io/en/latest/format.html)) has its own style guide: a set of conventions (sometimes arbitrary) about how to write code for that project. It is much easier to understand a large codebase when all the code in it is in a consistent style.

:::

1. Checkout a style guide for your Programming language and review your code for the readability considerations listed above.

- Would it make sense to adopt a style guide for your project?

- What conventions do you find useful?

2. Following style guides can be made easy with a [linter](https://github.com/caramelomartins/awesome-linters). Review your code by running a linter (e.g. `flake8` for Python, `checkcode` for MATLAB, `IntelliSense`for C++, or `lintr` for R) to identify conflicts with the style guide.

3. Make a todo list (GitHub issues) to improve the readability of your code.

:::success

**💡 Tip:**

For Python, the recommended docstring styles are the [Numpy](https://sphinxcontrib-napoleon.readthedocs.io/en/latest/example_numpy.html) and [Google](https://sphinxcontrib-napoleon.readthedocs.io/en/latest/example_google.html#example-google) styles. Both can be interpreted by sphinx.

::: -->

<!--

### 💪 Extra (optional) material -->

<!-- - Build your documentation with sphinx

- Read in the Turing Way about:

- [Software licenses](https://the-turing-way.netlify.app/reproducible-research/licensing/licensing-software.html)

- Data licenses and Machine Learning Model licenses.

- License compatibility (15 minutes)

- What happens when software licenses meet? To start understanding the concept of license compatibility, [this blog post](https://www.mend.io/resources/blog/license-compatibility/) on [mend.io](mend.io) is a good start.

- License compatibility in-depth case study (optional; 20 minutes)

- The Turing Way also discusses license compatibility with an [excellent in-depth analysis of a case study](https://the-turing-way.netlify.app/reproducible-research/licensing/licensing-compatibility.html). While this chapter is very informative, it goes quite deep into a specific case study, so it should be seen as illustrative rather than necessary background reading. -->

## Materials

- [Code Refinery lesson](https://coderefinery.github.io/documentation/)

- [TU Delft Research Software Policy](https://zenodo.org/record/4629662#.ZD7vJnZByUk)

- [TU Delft Guidelines on Research Software](https://d2k0ddhflgrk1i.cloudfront.net/TUDelft/Over_TU_Delft/Strategie/TU%20Delft%20Research%20Software%20Guidelines.pdf)

<!-- ## Notes

Sure, here is an outline for a code documentation workshop using Python as the main language:

I. Introduction

A. Overview of Code Documentation

B. Importance of Code Documentation

C. Types of Code Documentation

1. Inline Comments

2. Docstrings

3. External Documentation

D. Why Python?

II. Inline Comments

A. Syntax of inline comments

B. When to use inline comments

C. Best practices for writing inline comments

III. Docstrings

A. Syntax of docstrings

B. Types of docstrings

1. One-line docstrings

2. Multi-line docstrings

a. Google-style docstrings

b. NumPy-style docstrings

C. When to use docstrings

D. Best practices for writing docstrings

IV. External Documentation

A. Overview of external documentation

B. Tools for generating external documentation

1. Sphinx

2. Read the Docs

C. Best practices for writing external documentation

V. Conclusion

A. Review of key concepts

B. Final thoughts and recommendations

Note that you can add more content to each section based on the audience's needs and level of experience with Python and code documentation. -->

Sign in with Wallet

Sign in with Wallet