# Mije-Sokean Languages

The Mije-Sokean languages are spoken in the isthmus of of what is now known as "Mexico". It is spoken in the states of Veracruz, Tabasco, Oaxaca, and Chiapas. This region was called "yn nolmeca yn xicallanca" in La Historia Tolteca-Chichimeca. This means, "these people from a region of rubber, these people near the tree gourds" and it is where some scholars got the name "Olmeca" or "Olmec".

When the Mexica encountered the other languages to their south, they named them all "popoloca". This roughly translates to "those people from the region speaking jibberish" and has been used in ways very similar to the Greek word "βάρβαροι" and it's descendant "barbarian". However, it may also be related to the concept of "those who have been conquered". In the regional branches of Nahuatl the word branched into two versions: popoloca and popoluca. Nowdays, Popoloca refers to a portion of the Oto-Manguean that includes the Mazatecan languages, while Popoluca refers to the northern-most languages of the Mije-Soke tree in Veracruz.

## Present Day Language Distribution

[Jimenez, S. J. (2019). Estudios de la Gramática de la Oración Simple y Compleja En El Zoque De San Miguel Chimalapa. (Tesis Doctoral).](https://ciesas.repositorioinstitucional.mx/jspui/handle/1015/922)

From [Glottolog](https://glottolog.org/resource/languoid/id/mixe1284)

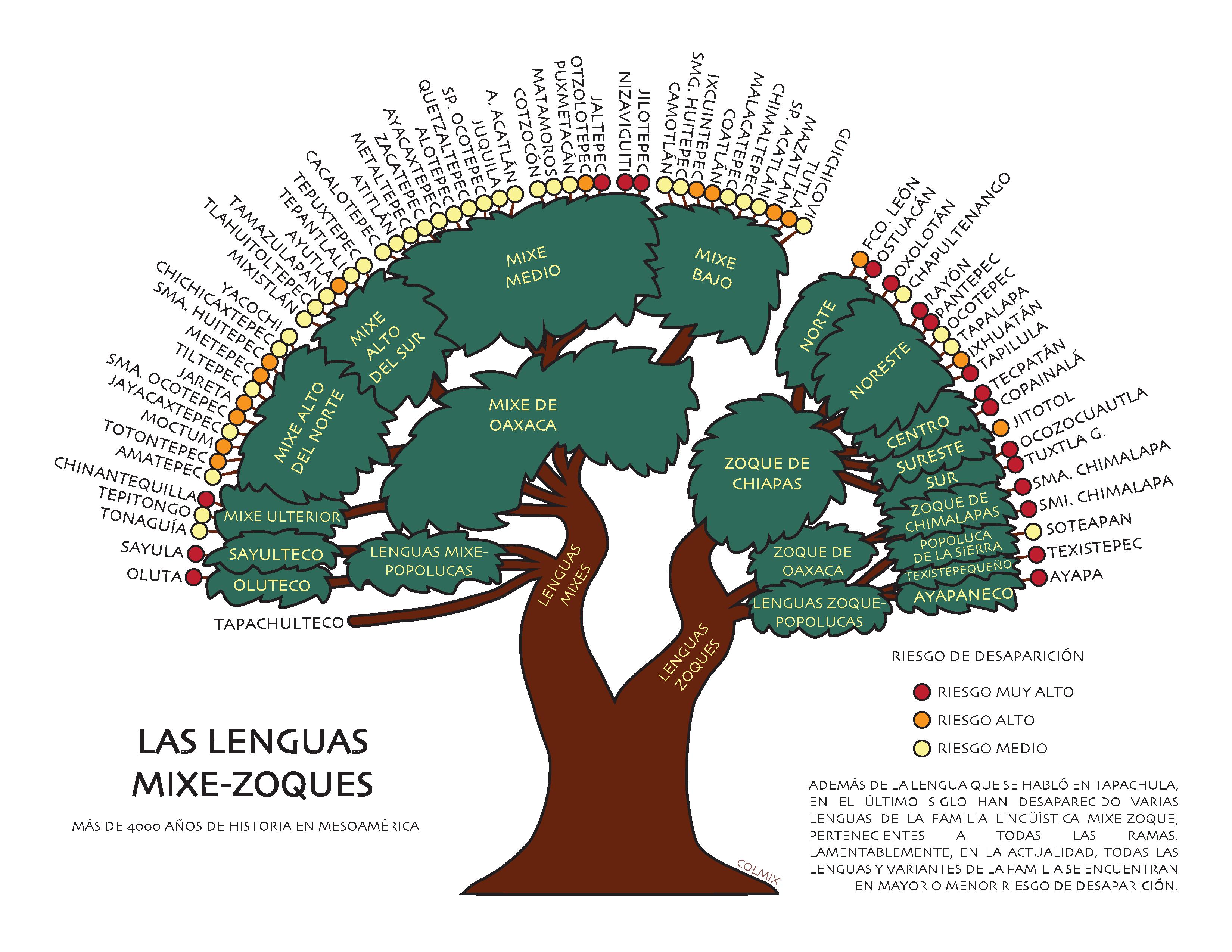

## Language Tree

* Mije-Soke ([Mixe-Zoque](https://glottolog.org/resource/languoid/id/mixe1284))

* Mijeano (Mixean, [Mixe](https://glottolog.org/resource/languoid/id/mixe1286))

* North Isthmus Mixean (Clark 2004)

* sayulteco

* t+kmaya’ (tʉcmay-ajw) [tɨkmajaʔ], yámay (yamay ajw) [ˈjamaj] (sayulteco, [Sayula Popoluca](https://glottolog.org/resource/languoid/id/sayu1241)) - Sayula, Veracruz, MX

* oluteco

* yaakaw+ [jaːkawɨ] (oluteco, [Oluta Popoluca](https://glottolog.org/resource/languoid/id/olut1240)) - Oluta, Veracruz, MX

* Mije ([Oaxaca Mixe](https://glottolog.org/resource/languoid/id/oaxa1241))

* ayöök [ʔajɤːkʰ] (mixe alto del norte) - Santa María Tlahuitoltepec, Santo Domingo Roayaga, Totontepec Villa de Morelos in Oaxaca, MX

* ayuujk [ʔajuːhkʰ] (mixe alto del centro) - San Pedro y San Pablo Ayutla, Santa María Tlahuitoltepec, Tamazulapam del Espíritu Santo in Oaxaca, MX

* ayuujk [ʔajuːhkʰ] (mixe alto del sur) - Mixistlán de la Reforma, Santa María Tepantlali, Santo Domingo Tepuxtepec in Oaxaca, MX

* ayuuk [ʔajuːkʰ] (mixe medio del este) - San Juan Cotzocón, San Juan Juquila Mixes, San Miguel Quetzaltepec, San Pedro Ocotepec, Santa María Alotepec, Santiago Atitlán, Santiago Zacatepec in Oaxaca, MX

* eyuk [ʔʌjukʰ] (mixe medio deloeste) - Asunción Cacalotepec, Santa María Alotepec in Oaxaca, MX

* ayuk [ʔajukʰ] (mixe bajo) - Camotlán, Coatlán, Matías Romero, Mazatlán, San Juan Guichicovi, Santo Domingo Petapa, Santo Domingo Tehuantepec in Oaxaca, MX

* tapachulteco ([Tapachultec](https://glottolog.org/resource/languoid/id/tapa1260)) - an extinct mije language from the border of Chiapas and Guatemala (Thomas & Swanton 1911). Ellison (1992), uses cognate lists to place it in Sokeano (Zoque), but I've read that grammar is more reliable for language family compared to cognates.

* Sokeano (Zoquean, [Zoque](https://glottolog.org/resource/languoid/id/zoqu1261))

* Sokeano del Gulfo ([Gulf Zoque](https://glottolog.org/resource/languoid/id/gulf1238))

* nuntaj+yi’ [nundahɨjiʔ], nunta anh+maatyi [nunda anhɨmaːtji] (popoluca de la Sierra, [Highland Popoluca](https://glottolog.org/resource/languoid/id/high1276)) - Soteapan, Veracruz, MX

* numte oote [nnumde o:te] (ayapaneco, [Tabasco Zoque](https://glottolog.org/resource/languoid/id/taba1264)) - Jalpa de Méndez, Tabasco, MX

* wää ‘oot [wɨː ʔoːt] (texistepequeño, [Texistepec Zoque](https://glottolog.org/resource/languoid/id/texi1237)) - Texistepec, Veracruz, MX

* Chimalapa Zoque

* angpø’n [ʔaŋpǝʔn], angpø’ntsaame [ʔaŋpǝʔn t͡saːme] (zoque del oeste, [Chimalapa Zoque](https://glottolog.org/resource/languoid/id/chim1300)) - San Miguel Chimalapas & Santa María Chimalapas in Oaxaca, MX

* Soke (Otetzame, [Chiapas Zoque](https://glottolog.org/resource/languoid/id/chia1261))

* ode [ʔode] (zoque del este) - Ixhuatán, Ocotepec, Tapilula in Chiapas, MX

* ode [ʔode] (zoque del norte bajo) - Ocotepec, Pantepec, Rayón, Tapalapa in Chiapas, MX

* ore [ʔoɾe] (zoque del norte alto) - Amatán, Chapultenango, Ixtacomitán, Juárez, Pichucalco, Reforma, Solosuchiapa in Chiapas, MX

* ore [ʔoɾe] (zoque del sureste) - Jitotol, Chiapas, MX

* ote [ʔote] (zoque del noroeste - Francisco León Chiapas, MX

* tsuni [t͡suni] (zoque del centro) - Copainalá, Ostuacán, Tecpatán, in Chiapas, MX

* tsuni [t͡suni] (zoque del sur) - Ocozocuautla, Tuxtla Gutiérrez in Chiapas, MX

[](https://colmix.org/?p=33)

## Historical Distribution

This map is from Stark & Eschbach (2018). The distributions only show the languages on the Gulf Coast. This is from 1876 and the distirbutions are very similar to present day distributions. However, it still doesn't show the break down into languages from the various language families.

Map from Kaufman & Justeson (2009).

**Note:** This map shows general possible outlines of the larger language families. Given the time depth, most of the languages would have already broken apart into the current distribution plus any extinct branches. Care must be taken to not misrepresent which languages were at each location:

* The spot of Mijean on the Pacific coast near the Guatemala/Chiapas border, that could have been a larger area and it should be labeled Tapachulteca [the modern Nawa name] or Huehueteca (Orellana 1995) [the old Nawa for "people of the ancient place"] .

* The two spots of Mijean inside of the Sokean, should be labeled sayulteco (tʉcmay-ajw or yamay ajw) and oluteco (yaakawʉ). They form the North Isthmus Mije group.

* The larger Mijean region in Oaxaca has all the ayöök, ayuujk, ayuuk, ayuk, and eyuk languages in their specific sub regions. This makes sense to divide according to Whichmann 2008, since they were likely larger families spoken elsewhere before the Mije moved away from both the other side of the Toltec split and the Excan Tlatolloyan into the highlands. However, this also means that it's possible that Mije took up more space in the Sokean region or that it took up space further north closer to the central valley where it's likely that Mije-Sokean was spoken in Teotihuacan (which I call Tamoanchan from the Tutunaku language).

* The larger Sokean region would still be broken up into nuntajɨɨyi, numte oote, wää ‘oot, angpø’ntsaame, ode, ore, ote, tsuni, and possibly other extinct varieties of Soke.

This map is from Calderón (2000). It only covers a small portion of the coast and it doesn't divide by language. It divides by estimated political regions while also showing language groups spoken. There's another map in this publication which shows the Alcadias Mayores that the area was later broken into (which is roughly this map, but grouped by common language familes).

This map is from Nielsen & Helmke (2011).

It still suffers from similar issues where only the language family extents are estimated. Though, it this case it easier to estimate roughly how the language families might be split up into the existing languages:

* The Soke region between Eastern Nawan and Olutek would be Sierra Popoluca.

* The Soke region between Chiapas Soke and the Sayultek, Olutek Mije, and Wave would be a sprectrum of numte oote and wää ‘oot.

* Additionally, the southeastern-most part of Chiapas Soke would actually be the Tapachulteca/Huehueteca Mije. This means that a possible reconstruction of the map could include another segment of Mije stretching down the Pacific coast, north of Wave, down into Guatamala.

This minimizes the Mije-Soke languages and expands the Nawan and Oto-manguean languages, but suffers from the same problems as the above maps, where it only places language groups and not specific branches of the languages would have already been present.

> This Linguistic Map by Nicholas Hopkins and Kathryn Josserand (2005); is based on the map by R. Longacre in Handbook of Middle American Indians, Vol. 5 (1967), and data from Lyle Campbell in The Linguistics of Southeast Chiapas (1988). <http://www.famsi.org/maps/linguistic.htm>

## Citations

* (Quauhtinchan, s. XVI) Historia Tolteca-Chichimeca, eds. Paul Kirchhoff, Lina Odena Güemes, y Luis Reyes García (México: CISINAH, INAH-SEP, 1976), 128, 152.

* > …yxquichime y yn tlatoque catca yn nolmeca yn xicallanca yn chane catca yn tlachiualtepec yn yacachto quipiaya yn imaltepeuh yn ipan maxitico yn tolteca

* My gloss:

```

√yxquich-i-me y yn √tlato-que catca

all.that-QUANT-LIG-ABS.PL POSS DEM lord-PL to.be-PAST

chief-PL

leader-PL

yn √ol-meca yn √xicall-anca

DEM rubber-person.from-PL.LOC DEM treegourd-person.near-PL.LOC

yn chane catca yn tla-√chiualtepe-c

DEM resident.SG to-be-PAST DEM INDN-build-hill-LOC

yn yacachto qui-√pia-ya yn im-√altepe-uh

DEM first-ADV 3-PL-keep-PAST DEM 3-PL-POSS-town-POSS

3-PL-POSS-watershed-POSS

yn ipan √maxiti-co yn √tol-teca

DEM when-TEMP arrive-PAST DEM reed-person.from.among-PL.LOC

complete-PAST

```

* My translation: "All that was there belonged to those leaders who were people from the place of rubber and people near the treegourds. Those resided at Tlachiualtepec — they first kept/guarded their town before those people from among the reeds arrived."

* > "Yeuantin y yn calmecactlaca yn tepeuani yn acico yn tlachiualtepec yn Chollolan"

* My gloss:

```

Yeuantin y yn calmecactlaca yn tepeua-ni

3-ABS.PL POSS DEF military DEF conquer-VN

yn aci-co yn tlachiualtepe-c yn Chollolan

DEF arrive-PAST DEF artificial.hill-LOC DEF area of those who fled.PL.LOC

```

* My translation: "Those belonging to this military might, this conqueror who arrived at this place of the artificial hill, this area of those who fled."

* [Sapper, K. (1897). Das Nördliche Mittel-Amerika nebst einum Ausflug nach dem Hochland von Anachuac. F. Vieweg.](https://archive.org/details/b24882732/page/244/mode/2up?q=zoque)

* > Eine zusammengehörige Sprachgruppe bilden die Mije-Sprachen, von welcher Mije und Populuca auf dem Isthmus verbreitet find, das Zoque im westlichen Chiapas seine Hauptverbreitung hat, die Tapachulteca, eine dem Aussterben nahe Sprache, aber eine isolirte, weit entsernte Insel im südlichsten Chiapas darstellt.

* "A related language group is formed by the Mije languages, of which Mije and Populuca are distributed on the isthmus, the Zoque having its main distribution in western Chiapas, representing Tapachulteca, a language near extinction but an isolated, distant island in southernmost Chiapas."

* Also has a few names of places in Zoque.

* [Thomas, C., & Swanton, J. R. (1911). Indian languages of Mexico and Central America and their geographical distribution. Bureau of American Ethnology. Bulletin, 44, p 65.](https://archive.org/details/indianlanguages00swangoog/page/n76/mode/1up)

* [Sapper, K. (1912). Über einige Sprachen von Südchiapas. In Proceedings of the Seventeenth International Congress of Americanists (1910) (pp. 295-320).](http://maya.polycorpora.org/Sapper1912.pdf)

* [Lehmann, W. (1920) Zentral Amerika. Berlin. II Band. pp. 790-794, 991-993.](https://www.google.com/books/edition/Zentral_Amerika/lq0PAQAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0)

* [González Casanova, P. (1927). El Tapachulteco no. 2 sin relación conocida. Revista Mexicana de Estudios Históricos, 1(2), 18-26.](https://www.worldcat.org/title/revista-mexicana-de-estudios-historicos/oclc/7344916)

* [Vivó, J. A. (1942). Geografía lingüística y política prehispánica de Chiapas y secuencia histórica de sus pobladores. Revista Geográfica, 2(4/5/6), 121-156.](https://www.jstor.org/stable/41888197)

* [Wonderly, W. L. (1949). Some Zoquean phonemic and morphophonemic correspondences. International Journal of American Linguistics, 15(1), 1-11.](https://www.jstor.org/stable/1262959)

* [Kaufman, T. (1964). Mixe-Zoque subgroups and the position of Tapachulteco. In Actas y memorias del XXXV Congreso Internacional de Americanistas (Vol. 2, pp. 403-411).](https://www.worldcat.org/title/xxxv-congreso-internacional-de-americanistas-mexico-1962-actas-y-memorias-2/oclc/835214047&referer=brief_results)

* [Becerra, M. E. (1985). Nombres geográficos indígenas del estado de Chiapas. Instituto Nacional Indigenista.](https://www.worldcat.org/title/nombres-geograficos-indigenas-del-estado-de-chiapas/oclc/651545121)

* [Campbell, L., & Kaufman, T. (1988). The Linguistics of Southeast Chiapas, Mexico. Papers of the New World Archaeological Foundation 50. Provo, UT: New World Archaeological Foundation.](https://www.worldcat.org/title/linguistics-of-southeast-chiapas-mexico/oclc/1035459204)

* [Ellison, B. F. (1992). Reconstructing proto-Mixe-Zoque. Language in context- essays for Robert E. Longacre. Hwang, S. J. J., & Merrifield, W. R. eds. Summer Institute of Linguistics.](https://www.sil.org/system/files/reapdata/33/28/09/3328093726212150008846887539802581991/31889.pdf)

* [Orellana, S. L. (1995). Ethnohistory of the Pacific coast. Labyrinthos, p 34.](https://archive.org/details/ethnohistoryofpa0000orel/page/33/mode/1up)

* Gives overviews of current theories based on archeology and linguistics for the departments of Suchitepéquez, Soconusco, and Esquintla.

* Suchitepéquez

> Campbell feels that although the present and historical distribution of Mixe-Zoque is not known to have extended beyond Ayutla, it is nearly certain that speakers of this linguistic group once occupied the Guatamalan costal corridor. Xinca, a language spoken east of Escuintla, has many Mixe-Zoque loanwords that could have been acquired only by contact, presumably with the native speakers in the hot country from Tapachula to El Salvador (Lowe et al. 1982:15).

* Soconusco

> Although the Mixe-Zoque presence in Chiapas may have been partiallt due to the ancient Olmecs, Lowe believes there was a constant Zoquean occupation of Southern Chiapas from the earliest ceramic-using period, or even before, and he does not accept the "Mixe-Zoque expansionist" model proposed by Kaufman for the Olmecs (1977:200-201). Kaufman (1976:107) has stated, however, that he thinks that Soconusco was basically Tapachultec-speaking from 1400 B.C. to A.D. 100. Tapachultec is a Mixean language.

> <br/>...<br/>

> Three important languages coexisted in Soconusco at the time of the conquest. The least common was Nahuatl, which was spoken in the area as a result of the Aztec conquest at the end of the fifteenth century (Campbell 1988:277). After the Spanish conquest Nahuatl continued in use in Huehuetan and Talibe (Gerhard 1979:170). In post conquest times Nahuatl-speaking native leaders went to Heuhuetan and continued to use the old official language (Coe 1961:22).<br/><br/>A second and much more common language spoken in Soconusco before the conquest was a dialect of Nahua often called "corrupt Mexican" in the the colonial literature. The persistance of this dialect in many towns long after Nahuatl dissapeared suggests that the Nahua-speaking population of Soconusco constituted a substantial colony (Thomas 1974:27). The extensive use of "Mexican" as a second language is well documented. Ciudad Real (1873:294) said it was the laguage of trade for the Indians in Soconusco, and this was no doubt true in prehispanic times, too.<br/><br/>The Nahua speakers were said to have come from Veracruz, and Pipil does share linguistic features with Gulft Coast Nahua (Campbell 1976b:14). The Pipils left Soconusco around A.D. 800-900, which correlates well with the glottochronological date for the Pipil split of some eleven (minimum) centuries ago. Apparently some of these people remained in Soconusco, becoming "corrupt Mexican" speakers, or, in modern times, Walwi speakers (Campbell 1988:268,279).<br/><br/>The third and apparently dominant language of Soconusco was Huehueteca, so called from the early reference of Garcia de Palacio to "bebetlateca" as the maternal language of Suconusco (1927:72). Ciudad Real related that Fray Alonso Ponce's party first encountered this language in Tliltepec (Tiltepec). Huehueteca might have been a regional dialect of Zoque rather than another Zoquean language. Ciudad Real stated that the language "much resembles Zoque," but noted that it contained some words from Yucatan. Those words may have been borrowes from adjacent Maya groups. This language was spoken in almost all the towns of Soconusco (1873:293-94; Thomas 1974:27-28).<br/><br/>Huehueteca survived mainly as Tapachultec, which is part of the Mixean branch of the Mixe-Zoque language family (Campbell 1988:305). Tapachultec also has some Maya loanwords. There is a non-Mixe-Zoque element in Tapachultec that may be a relic of Pipil contact, or it could represent a substratum of the of Soconusco prior to the pre-classic. The Mixe-Zoque languages spread out from the Isthmus of Tehuantepec about 1600 B.C. (Kaufman 1976:106).<br/><br/>Campbell acknowledges that Huehueteca has been identified as Ciudad Real's "Zoque-like" language, but says it may have been a Nahua language. From modern indications it would appear that Nahuatl, Nahua (Waliwi), and some third unidentified language were all spoken in Soconusco, and he feel that the identity of HueHueteca is still uncertain. Campbell says the Soconusco was more linguistically complex than Ciudad Real's description suggests (1988:279,306).

* Escuintla

> Documentary information places the first Nahua, or Pipil, speakers in Escuintla around A.D. 800-900 (Torquemada 1984,1:333). Some investigators have hypothesized even earlier dates for the Pipil arrival in the area. It has frequently been assumed that Nahua was spoken by the peoples of Teotihuacan and Cotzumalhuapa. According to Campbell this is highly unlikely. Nahua does not have the time depth to have been spoken by these cultures. Even if the Teotihuacanos did migrate to the coastal areas they would not, then, have been responsible for the introdyction of Nahua.<br/><br/>Nahua loanwords found in languages throughout Mesoamerica correlate only with Toltec or Aztec cultures. The Nahua entrance into coastal Chiapas and Guatemala correlates with the fall of Teotihuacan and involves cultures that predominated after that time (Campbell 1976b:19,22). The southern Veracruz dialects, the Central American dialects, and the Chiapas Nahua dialects are more closely related to one another than to other variaties of Nahua. The Pipils were presumed to have been in Veracruz before their arrival in Soconusco (Campbell 1988:290).<br/><br/>Xinca speakers were not responsible for Cotzumalhuapa or earlier Escuintla cultures either, as they were probably not present on the coast until pushed southward quite late by expanding Quiche groups. Many Xinca floral terms representing peidmont ecology are borrowed, strongly implying that those people were relatively recent immigrants to the coast (Campbell 1976b:21).<br/><br/>It is difficult to determine which linguistic group or groups occupied the Escuintla area before A.D. 800-900. Lenca, Chol, and Moyutla speakers are possibilities, as all of these languages were spoken in adjacent areas. Perhaps Mixe-Zoque was spoken in Escuintla since this language group, and Campbell and Kaufman have shown, seems to be present wherever Olmec or Izapa culture existed (Feldman 1977:5-6). Kaufman (1976:114-17) suspects that the Tapachultec language may have been spoken by those of Cotzumalhuapa.

* [Léonard, E., & Velázquez, E. (2000). El Sotavento veracruzano: procesos sociales y dinámicas territoriales. CIESAS.](https://www.researchgate.net/publication/303787119_El_Sotavento_veracruzano_procesos_sociales_y_dinamicas_territoriales)

* Calderón, A. D. (2000). La conformación de regiones en el Sotavento veracruzano: una aproximación histórica. El Sotavento veracruzano: procesos sociales y dinámicas territoriales, 27.

* Cited in: [Doering, T. F. (2007). An Unexplored Realm in the Heartland of the Southern Gulf Olmec: Investigations at El Marquesillo, Veracruz, Mexico. Graduate Theses and Dissertations.](https://digitalcommons.usf.edu/etd/696/) [**Note:** this thesis does pull in some weird ideas, but that's not uncommon, lots of people make connections with orientalism even if it is just a coincidence.]

* [Clark, L. E. (2004). A Comparison of Person Markers in Sayula and Oluta Popoluca. SIL Electronic Working Papers 2004-2006.](https://www.sil.org/system/files/reapdata/66/87/55/66875593268870855242311048268999220837/silewp2004_006.pdf)

* [Sandstrom, A. R., & Valencia, E. H. G. A. (Eds.). (2005). Native peoples of the Gulf Coast of Mexico. University of Arizona Press.](https://www.google.com/books/edition/Native_Peoples_of_the_Gulf_Coast_of_Mexi/qiqN2ziI_eYC?hl=en&gbpv=0)

* [INALI. (2009) Catálogo de las lenguas indígenas nacionales. Variantes lingüísticas de México con sus autodenominaciones y referencias geoestadísticas.](https://site.inali.gob.mx/pdf/catalogo_lenguas_indigenas.pdf)

* [Wichmann, S. (2008). Om opdagelsen af et gränseoverskridende nyt sprog. In De mange veje til Mesoamerika: Hyldestskrift til Una Canger (pp. 63-80). Afdelingen for Indianske Sprog og Kulturer, Københavns Universitet.](https://www.academia.edu/13247117/Wichmann_S%C3%B8ren_2008_Om_opdagelsen_af_et_gr%C3%A6nseoverskridende_nyt_sprog_In_Nielsen_Jesper_and_Mettelise_Fritz_Hansen_eds_De_mange_veje_til_Mesoamerika_Hyldestskrift_til_Una_Canger_pp_63_80_K%C3%B8benhavn_K%C3%B8benhavns_Universitet)

* [Kaufman, T., & Justeson, J. (2009). Historical linguistics and pre-Columbian Mesoamerica. Ancient Mesoamerica, 20(2), 221-231.](https://www.researchgate.net/publication/232023322_Historical_linguistics_and_pre-columbian_mesoamerica)

* [Nielsen, J., & Helmke, C. (2011). Reinterpreting the Plaza de los Glifos, La Ventilla, Teotihuacan. Ancient Mesoamerica, 22(2), 345-370.](https://www.academia.edu/3859848/Reinterpreting_the_Plaza_de_los_Glifos_La_Ventilla_Teotihuacan)

* [Stark BL, Eschbach KL (2018) Collapse and diverse responses in the Gulf lowlands, Mexico. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology. 50, 98-112. DOI: 10.1016/j.jaa.2018.03.001](https://archive.org/details/mccl_10.1016_j.jaa.2018.03.001/mode/1up&sa=D&source=editors&ust=1658091950134405&usg=AOvVaw3DBdPr99ywjsh0377o8OQ6)

* Hammarström, Harald & Forkel, Robert & Haspelmath, Martin & Bank, Sebastian. 2022. Glottolog 4.6. Leipzig: Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6578297 (Available online at http://glottolog.org, Accessed on 2022-07-12.)

* Rodríguez, E. (2022, July 12). Cuando la identidad está fortalecida lo primero que se demuestra es el respeto y espera el mismo respeto de los. [Status update]. Facebook. https://www.facebook.com/permalink.php?story_fbid=pfbid0LBdJbtAGbwQBTb2bJ8EjNNDo8GLpS7zuxi72snP15sgDuJ4pTxsgj3qkhLjMnSh1l&id=100018170461976

* Popoloca derivation:

* |po-|(reduplication) + |poloa| + |-cah| (group of people)

* [Popoluca](https://nahuatl.uoregon.edu/content/popoloca)

* [popoloca](https://nahuatl.uoregon.edu/content/popoloca-0)

* [popolotza](https://nahuatl.uoregon.edu/content/popolotza)

* [popoloa](https://nahuatl.uoregon.edu/content/popoloa)

* [popoloni](https://nahuatl.uoregon.edu/content/popoloni)

* [poloni](https://nahuatl.uoregon.edu/content/poloni)

* [poloa](https://nahuatl.uoregon.edu/content/poloa)