# HTB academy - Web Request && MDN Web Docs - HTTP

###### tags: `HTB` `Mozilla.org`

## HTTP

HTTP is an **application-level protocol** used to access resources over the World Wide Web. **The term hypertext** stands for text containing links to other resources and text that can be easily interpreted by the readers.

HTTP communication consists of a client and a server, where the client requests the server for a resource. The server processes the requests and returns the requested resource. The default port for HTTP communication is 80; however, this can be changed.

Resources over HTTP are accessed via a **Uniform Resource Locator**(URL). Let's look at the structure of a URL.

|Component | Description|

|----------|---------------|

|Scheme | This is used to identify the protocol being accessed by the client. This is usually http or https.|

|User Info | This is an optional component that contains credentials in the form username:password, which is used to authenticate to the host.|

|Host | The host signifies the resource location. This can be a hostname or an IP address. A colon separates a host and port.|

|Port | URLs without a port specified point to the default port 80. If the HTTP server port isn't running on port 80, it can be specified in the URL.|

|Path | This points to the resource being accessed, which can be a file or a folder. If there no path specified, the server returns the default index document hosted by it (for example, index.html).|

|Query String | The query string is preceded by a question mark (?). This is another optional component that is used to pass information to the resource. A query string consists of a parameter and a value. In the example above, the parameter is login, and its value is true. There can be multiple parameters separated by an ampersand (&).|

|Fragments | This is processed by browsers on the client-side to locate sections within the primary resource.|

Not all components are always required to access a resource. However, a URL should at least contain a scheme and host to make a proper request.

1. The first time a user enters a URL (inlanefreight.com) into the browser, **it requests a DNS server to resolve the domain. The DNS server looks up the IP address** for inlanefreight.com and returns it. All domain names need to be resolved this way, as **a server can't communicate without an IP address**.

2. Next, the **browser sends a GET request** to the default HTTP port, i.e., 80, asking for the root / folder. Here GET is the request method. The type of request can vary, as we'll see later. The web server receives the request and processes it. By default, servers are configured to return an index file when a request for / is received. In this case, **the contents of index.html are read and returned by the webserver as an HTTP response**. The response also contains information such as the status code 200 OK, meaning the request processed successfully.

The index.html contents are then rendered by the web browser and presented to the user. **HTML** (HyperText Markup Language) **is a client-side language** that is understood and processed by browsers. It is the standard markup language to display documents via a web browser. HTML pages are assisted by **Cascading Style Sheets (CSS), which allow flexibility for applying presentation elements such as layout, colors, and fonts to one or multiple web pages as well as scripting languages such as JavaScript which enable interactive web pages**.

## HTTPS

One of the **major drawbacks of HTTP is that all data is transferred in clear text**, meaning anyone between the source and destination can perform a **Man-in-the-middle** (MiM) attack to view the transferred data. This is a major issue with banking and government websites, which contain sensitive user data.

This can be examined by using a network analyzer such as Wireshark. The following example demonstrates the effect of not enforcing secure communications between a web browser and a web application. If we attempt to log in to an insecure website while monitoring the network traffic using a graphical packet network protocol analyzer such as Wireshark, we can see that the login credentials can be intercepted in cleartext. This would make it easy for someone on the same network (such as a public wireless network) to capture them and use them for malicious purposes.

These drawbacks gave rise to the HTTPS (HTTP Secure) protocol. When this protocol is enabled, all communication between the client (user accessing a web application via their web browser), and the webserver that hosts the web application, is encrypted. When HTTPS is implemented on a web application, it becomes impossible for anyone to intercept and analyze the traffic and capture information such as credentials and other sensitive data.

Websites that enforce HTTPS can be identified through https:// in the URL (i.e., https://www.google.com) as well as the lock icon in the address bar of the web browser, to the left of the URL.

## HTTPS FLOW

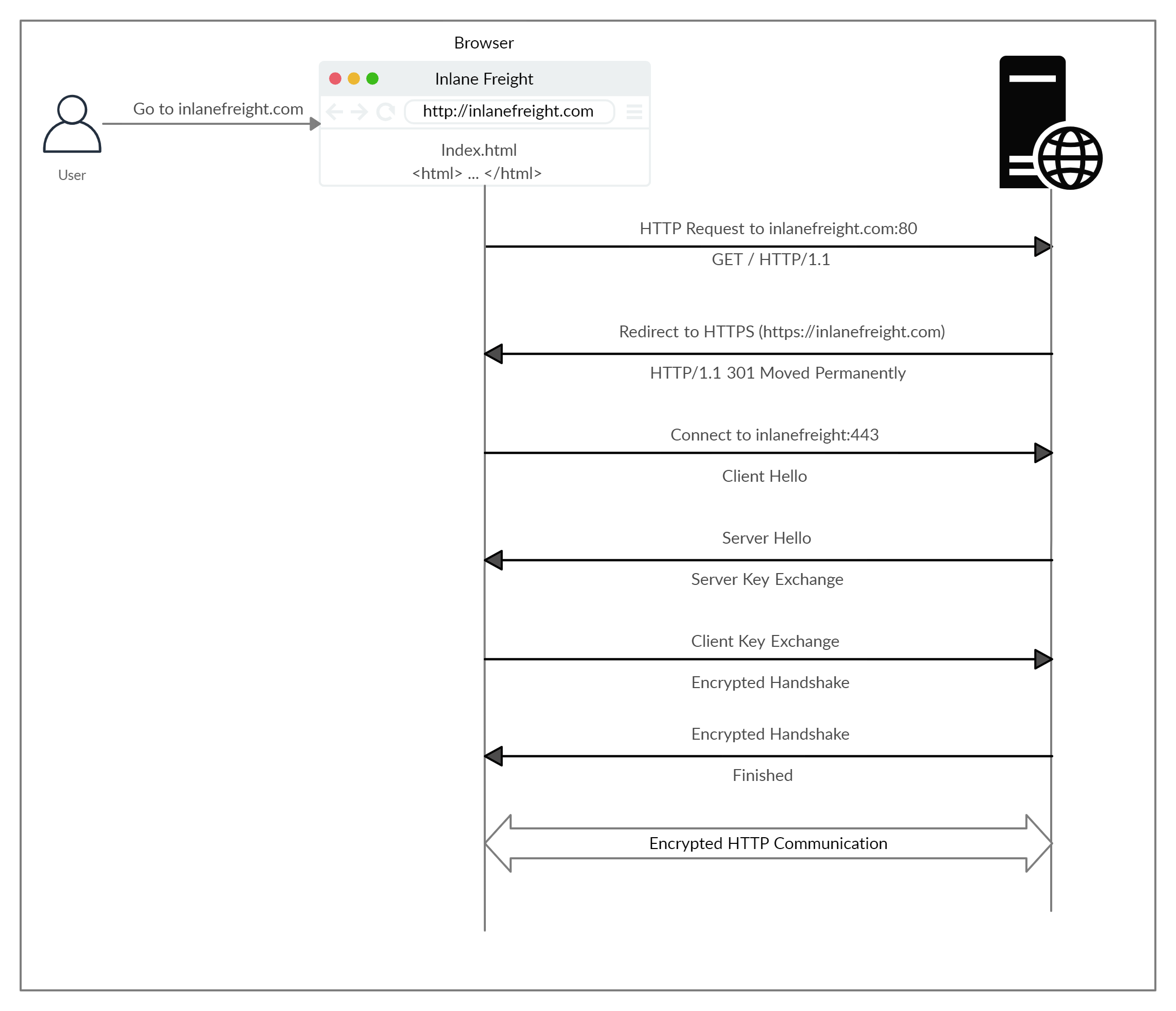

Upon browsing to http://inlanefreight.com, the browser attempts to resolve the domain and redirects the user to the webserver hosting the target website:

1. A request is sent to port 80 first, which is the unencrypted HTTP protocol. The server detects this and redirects the client to secure HTTPS port 443 instead. This is done via the 301 Moved Permanently response code. We will discuss the various types of response codes returned by an HTTP server later in this module.

2. Next, the client (web browser) sends a "client hello" packet, giving information about itself. After this, the server replies with "server hello", followed by a key exchange. The client verifies this key and sends one of its own. After this, an encrypted handshake is initiated to verify if the encryption and transfer are working properly.

3. Once the handshake completes successfully, normal HTTP communication is continued, which is encrypted thereafter. This is a very high-level overview of the key exchange, which is beyond this module's scope.

Depending on the circumstances, an attacker may be able to perform an HTTP downgrade attack, which downgrades HTTPS communication to HTTP. This is done by setting up a man-in-the-middle (MITM) attack and proxying (passing) all traffic through the attacker's host without the user's knowledge. A successful downgrade attack would result in the cleartext transfer of HTTP data, which the attacker can log and later examine or manipulate for malicious purposes.

## HTTP Request

### Start line

HTTP requests are messages sent by the client to initiate an action on the server. Their start-line contain three elements:

1. An HTTP method, a verb (like GET, PUT or POST) or a noun (like HEAD or OPTIONS), that describes the action to be performed. For example, GET indicates that a resource should be fetched or POST means that data is pushed to the server (creating or modifying a resource, or generating a temporary document to send back).

2. The request target, usually a URL, or the absolute path of the protocol, port, and domain are usually characterized by the request context. The format of this request target varies between different HTTP methods. It can be

* An absolute path, ultimately followed by a '?' and query string. This is the most common form, known as the origin form, and is used with GET, POST, HEAD, and OPTIONS methods.

POST / HTTP/1.1

GET /background.png HTTP/1.0

HEAD /test.html?query=alibaba HTTP/1.1

OPTIONS /anypage.html HTTP/1.0

* A complete URL, known as the absolute form, is mostly used with GET when connected to a proxy.

GET https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/HTTP/Messages HTTP/1.1

* The authority component of a URL, consisting of the domain name and optionally the port (prefixed by a ':'), is called the authority form. It is only used with CONNECT when setting up an HTTP tunnel.

CONNECT developer.mozilla.org:80 HTTP/1.1

* The asterisk form, a simple asterisk ('*') is used with OPTIONS, representing the server as a whole.

OPTIONS * HTTP/1.1

3. The HTTP version, which defines the structure of the remaining message, acting as an indicator of the expected version to use for the response.

### Hearders

HTTP headers from a request follow the same basic structure of an HTTP header: a case-insensitive string followed by a colon (':') and a value whose structure depends upon the header. The whole header, including the value, consist of one single line, which can be quite long.

Many different headers can appear in requests. They can be divided in several groups:

* General headers, like Via, apply to the message as a whole.

* Request headers, like User-Agent, Accept-Type, modify the request by specifying it further (like Accept-Language), by giving context (like Referer), or by conditionally restricting it (like If-None).

* Representation metadata headers (formerly entity headers), like Content-Length that describe the encoding and format of the message body (only present if the message has a body).

### Body

The final part of the request is its body. **Not all requests have one**: requests fetching resources, like GET, HEAD, DELETE, or OPTIONS, usually don't need one. Some requests send data to the server in order to update it: as often the case with POST requests (containing HTML form data).

Bodies can be broadly divided into two categories:

* Single-resource bodies, consisting of one single file, defined by the two headers: Content-Type and Content-Length.

* Multiple-resource bodies, consisting of a multipart body, each containing a different bit of information. This is typically associated with HTML Forms.

## HTTP Response

### Status line

The start line of an HTTP response, called the status line, contains the following information:

1. The protocol version, usually HTTP/1.1.

2. A status code, indicating success or failure of the request. Common status codes are 200, 404, or 302

3. A status text. A brief, purely informational, textual description of the status code to help a human understand the HTTP message.

A typical status line looks like: HTTP/1.1 404 Not Found.

### Headers

HTTP headers for responses follow the same structure as any other header: a case-insensitive string followed by a colon (':') and a value whose structure depends upon the type of the header. The whole header, including its value, presents as a single line.

Many different headers can appear in responses. These can be divided into several groups:

* General headers, like Via, apply to the whole message.

* Response headers, like Vary and Accept-Ranges, give additional information about the server which doesn't fit in the status line.

* Representation metadata headers (formerly entity headers), like Content-Length that describe the encoding and format of the message body (only present if the message has a body).

### Body

The last part of a response is the body, **usually be HTML, JS or images**. Not all responses have one: responses with a status code that sufficiently answers the request without the need for corresponding payload (like 201 Created or 204 No Content) usually don't.

Bodies can be broadly divided into three categories:

* Single-resource bodies, consisting of a single file of known length, defined by the two headers: Content-Type and Content-Length.

* Single-resource bodies, consisting of a single file of unknown length, encoded by chunks with Transfer-Encoding set to chunked.

* Multiple-resource bodies, consisting of a multipart body, each containing a different section of information. These are relatively rare.

## HEADER

HTTP headers provide an additional way to pass **information between the client and the server** or **info about the body, such as content type, length, proxy or encoding**. There are headers specific to requests and responses as well as general headers common to both. Headers can have one or multiple values appended after the header name and separated by a colon. There are many headers used for different purposes, which are divided into different categories:

1. General Headers

2. Entity Headers

3. Request Headers

4. Response Headers

5. Security Headers

## Burp

**Burp Suite is a tool that acts as a proxy server** and can be used to examine and modify HTTP requests. It provides a proxy that can route traffic from the browser through the proxy and view the various requests and responses between the client (web browser) and the webserver.

## cURL

cURL (client URL) is a command-line tool and library which primarily supports HTTP along with many other protocols. This makes it a good candidate for scripts as well as automation. The tool takes in at least one argument, i.e., the resource to fetch.

Unlike browsers, cURL can't render HTML and run JavaScript, meaning the entire response is provided to us raw. As we can see above, the server returned a 401 Unauthorized page as we didn't specify the credentials. It's possible to view the raw HTTP requests using the "-v" switch to increase verbosity.