---

created: 2023-05-03T16:27:23 (UTC -07:00)

tags: []

source: https://graymirror.substack.com/p/the-golden-age-of-informal-securities?utm_source=profile&utm_medium=reader2

author: Curtis Yarvin

---

# The golden age of informal securities - by Curtis Yarvin

> ## Excerpt

> "A disturbing discovery that offers plenty of answers, but no solutions."

---

Figuring out that the whole centuries-old Anglo-American financial operating system is deeply broken and cannot, by any means short of a military coup, be repaired, is like being an 11-year-old and figuring out that your parents are alcoholics: a disturbing discovery that offers plenty of answers, but no solutions.

Larry Summers, god-emeritus of the Treasury, has some answers. He [says](https://archive.is/HtXzL):

> In general, bank accounting probably doesn’t fully capture some of the risks associated with this pattern of borrowing short and lending long.

_You don’t say?_ Dr. Summers could try reading my [15-year-old blogpost](https://www.unqualified-reservations.org/2008/09/maturity-transformation-considered/), or even this [80-year-old book](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Human_Action). He is probably a little busy for blogposts and books, though. Sad. Note to Big Larry: borrowing short and lending long (maturity transformation) is what an Anglo-American bank _does_. And has been doing for [300 years and change](https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/about/history). And in that time, there have been… a number of crises. The last one, they tell us, has happened.

A very cogent explanation of the banking crisis by a professional true believer is [this Patrick McKenzie essay](https://www.bitsaboutmoney.com/archive/banking-in-very-uncertain-times/). See also [his essay](https://www.bitsaboutmoney.com/archive/deposit-insurance/) on “deposit insurance,” from last summer, which ends:

> It is difficult to overstate how important \[deposit insurance\] is. You rely on it to the same degree as you do electricity, running water, and stable Internet connections. Like much infrastructure, it is so good you’ll hopefully never even have to realize it is there.

Hopefully! Well, we have not had a systemic banking crisis in _over_ 15 years. Imagine if nuclear power had this kind of safety record, and “vanishingly few nuclear accidents” just meant, like, you couldn’t enter the whole state of Oregon for the next half-century.

It’s _fine!_ It’s just _one state!_ Everything is fine! You may never see Oregon—but your _kids_ could! Besides, what _is_ there to see in Oregon? And don’t you like _electricity?_ Huh?

The mentality of [Boxer](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Boxer_(Animal_Farm)) in _Animal Farm_ is everywhere. Ultimately, as Maistre wrote in his treatment of the French Revolution, “every man is convinced that he is being well governed, so long as he himself is not being killed.”

Our ancient ramshackle financial system is just one shard of our ancient ramshackle governance system. If like many _Gray Mirror_ readers you are a programmer, think of it as an ancient codebase. McKenzie, a [programmer](https://news.ycombinator.com/user?id=patio11), thinks about finance the way most people do: in the language of the ancient program. Because this program is absurdly complex and breaks every five minutes, McKenzie’s explanation is absurdly complex and his assurances break in nine months.

There is one tiny picture of a different world in his essay. This world horrifies him:

> Banks engage in maturity transformation, in “borrowing short and lending long.” Deposits are short-term liabilities of the bank; while time-locked deposits exist, broadly users can ask for them back on demand. Most assets of a bank, the loans or securities portfolio, have a much longer duration.

>

> _Society depends on this mismatch existing_. It must exist _somewhere_. The alternative is a much poorer and riskier world.

In _a free-market financial system_, interest rates would be set by _supply and demand_. In this hypothetical system, which has existed in the [past](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bank_of_Amsterdam) but does not exist anywhere today, _every borrower has an equal and opposite lender_. If you want to borrow money for 30 years, find someone who wants to lend money for 30 years.

This design is stable because, borrowing genuine and exogenous cataclysms (asteroid strike, pandemic, etc), neither the demand _for_, nor the supply _of_, loanable funds, has _any_ reason to change rapidly. Anything that cannot change rapidly is stable. Duh.

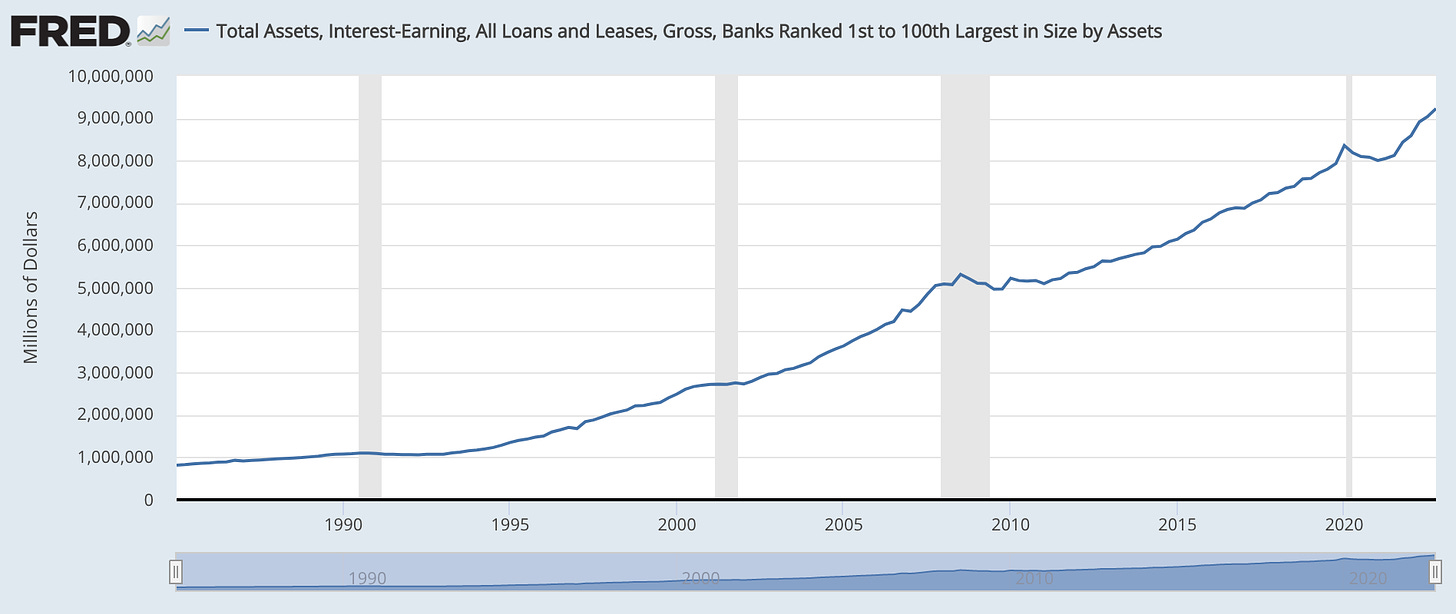

_That_ would be capitalism. This is _not_ how our financial system works. _Our_ financial system is powered by continuously increasing systemic debt which is never repaid:

[

](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F5c1b2655-b0a6-4fe5-9892-27cf7b56d13a_1896x800.png)

What this graph means is that _the whole economy chronically loses money_. Notice those moments where debt goes flat or even down? These are called “recessions.” When any system, big or small, goes tits up unless it can keep borrowing, _it is losing money_.

What McKenzie means by “poorer and riskier” is that if you take any money-losing machine, big or small, and you stop lending to it, _it explodes_. If you don’t want to _(a)_ kick the can down the road by borrowing more, and _(b)_ you don’t want the can to explode, you have to _(c)_ _restructure_ it. But try restructuring a whole economy without a military coup—or any other source of total power.

You might say that technology has improved a lot since 1985. So there should be a lot more debt. Because we have faster computers and sharper TVs. Take a moment to think about whether this makes sense. Take another moment to think about how long you spent just _assuming_ it made sense. “Growth.” Think about that word—“growth.” What does it mean—besides, of course, a tumor?

In _capitalism_, the amount of debt an economy carries should depend on its capital base, ie, the amount of future production that has to be paid for in the present—by building _things_ that cost in the present, but produce in the future. Like factories. Since we so _rationally_ moved all our factories to China, finding it more pleasurable to live by consuming in the present, we Americans should be carrying _less and less_ debt. Hm.

As for houses—are our houses getting bigger and nicer? At the rate they are getting more and more expensive? If every 30-year mortgage needed to be lent by a 30-year saver (perhaps a new graduate saving for retirement), resulting in a 10% interest rate for 30-year money, maybe… housing prices would be _a little lower?_ Supply, demand…

But this is in a fantasy world of true capitalism which we simply can’t get to from here—not without somehow using [$5T of actual dollars](https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/BOGMBASE) to repay [$125T of financial assets](https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/FBTFASQ027S). Which would involve a certain amount of… _repricing_. Of… everything.

Yes, the free market could do this. If you wanted the free market to do this, you _could_. “Poorer and riskier” would be a _slight_ understatement. I am more given to hyperbole than Patrick McKenzie—I might have written “cannibal zombies walking the streets.” _You can’t get there from here._ Not in any way you would want to.

So it is _true_ that society depends on “maturity transformation existing”—not because MT is _good_, but just because there is _no safe and easy way to turn it off_.

But what is the _easiest_ safe way? And what is the easiest way to at least _think_ about it?

Modeling banks as “private companies” and “deposit insurance” as insurance is like modeling the sun as going around the earth: it actually kind of _works_. You can even predict eclipses with a purely geocentric astronomy. It takes a ton of epicycles—as you can see by reading the McKenzie posts. Why not a simpler model?

A “heliocentric” model of fiat currency starts by defining fiat currency as _state equity_. A “Federal Reserve Note” is a _share of stock in the government_. The relationship between Microsoft and MSFT common stock is the same as the relationship between the USG and FRNs: Microsoft can create and destroy all the shares it wants, and an MSFT share entitles you only to equal treatment to all other MSFT shareholders (“equity”).

When you pay your taxes (note that the heliocentric model also neatly explains [MMT](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Modern_Monetary_Theory)), you are returning USG shares to the USG to be destroyed. When the Fed pays [interest on reserves](https://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/reserve-balances.htm), this is a dividend—Microsoft does not pay dividends in Microsoft shares, but it easily could. (Note the case of [TNB](https://www.chicagobooth.edu/review/safest-bank-fed-wont-sanction)—it’s not what you might [think](https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/TNB), you swine.)

We then unify Fed and Treasury, which are both organs of the USG. This allows us to model Treasury bonds (technically, bond _coupons_) as _restricted_ stock—many Microsoft employees are paid in MSFT shares which are invalid until some vesting date. This corresponds exactly to a future bond payment.

Now to banking. When you “deposit” (note the Orwellian language) $1000 in Wells Fargo, you are _lending_ 1000 FRNs to Wells Fargo, in a zero-term auto-renewing loan. Every millisecond, you lend a thousand dollars to the bank, due the next millisecond. If you don’t “withdraw” your money in the next millisecond, you lend it to WF again.

Another way to say this is that you give WF 1000 FRNs, in exchange for 1000 “WF-FRNs,” which WF promises to redeem for actual FRNs. The value of one WF-FRN is _at most_ one FRN_—_discounted by the nonzero probability that WF will fail.

The trouble with this design is that “depositing” is a _money-losing transaction_, since the value of an WF-FRN is always _less_ than the value of an FRN. The exact value of a WF-FRN is the value of an FRN, _minus_ the value of a _[credit default swap](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Credit_default_swap)_ (CDS) on WF.

But since the USG can create infinite FRNs, just as Microsoft can create infinite MSFT shares, the USG can create infinite CDS that pay off in FRNs.

Therefore, “deposit insurance” means the USG, loving Wells Fargo as it does, gives you an extra security whenever you lend money to Wells Fargo. Wells Fargo gives you a WF-FRN, and the USG gives you a WF-CDS. One WF-FRN plus one WF-CDS has _exactly_ the value of one FRN. “Deposit” away!

But wait! Since WF is an [SIB](https://www.fsb.org/2022/11/2022-list-of-global-systemically-important-banks-g-sibs/), you can “deposit” any amount of FRNs “in” Wells Fargo. But First Republic is _not_ an SIB! So when you lend your FRNs to [FR](https://www.nytimes.com/live/2023/03/16/business/banking-crisis-stocks-market-news), you only get up to $250,000 of FR-CDS. Above that number—better to redeem your _naked_ FR-FRNs for actual FRNs, then lend them to WF, for fully protected WF-FRN/WF-CDS pairs. This is a _strictly profitable transaction_—so everyone should do it.

But wait! Silicon Valley Bank was not an SIB. Yet everyone was assuming it would work like an SIB—and it _did_ work like an SIB. It turned out that if you had $500K “in” SVB, you had 500,000 SVB-FRNs, 250,000 SVB-CDS, _and_—250,000 _SVB-iCDS._

We have found our _informal securities_. On paper, the SVB-iCDS _did not exist_. But thousands of competent professionals and billions of dollars _acted as if they did_. Surprise: they _did_ exist. Were you surprised? I wasn’t surprised.

The USG’s commitment to these informal securities—both to their _existence_, and to their _informality_—is rock-solid. Let’s go to the [tape](https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Bcvl104tyRY). Senator Lankford of Oklahoma asks Treasury Secretary Yellen:

> Will the deposits in every community bank in Oklahoma, regardless of their size, be fully insured now? Regardless of the size of the deposit, will they get the same treatment that SVB just got?

Secretary Yellen responds:

> A bank only gets that treatment if a majority of the FDIC board, a supermajority of the Fed board, and I in consultation with the President determine that the failure to protect uninsured depositors would create systemic risk.

Thus if you have $500000 “in” the Bank of Oklahoma, you have 500,000 BO-FRNs, 250,000 BO-CDS, and 250,000 _BO-iCDS_—an _informal security_ which depends on what Secretary Yellen and other dignitaries _had for breakfast_. This, ladies and gentlemen, is _Third World finance_—an _extralegal property right_. [Hernando de Soto](https://www.amazon.com/Mystery-Capital-Capitalism-Triumphs-Everywhere/dp/0465016154), call your office.

It’s actually way worse than this. Even with Wells Fargo, you don’t actually get a WF-CDS issued by the USG. Your CDS is issued by something called “FDIC,” which is either a government agency or a private company—no one is [quite sure](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/State-owned_enterprises_of_the_United_States). So for your $500K deposit in Wells Fargo, you get 500,000 WF-FRNs and 500,000 WF-FDIC-CDS.

FDIC, unlike the Fed, cannot issue FRNs. And it has written trillions of FDIC-CDS—but it only has billions of FRNs. What happens if FDIC runs out of FRNs? Do all the FDIC-CDS expire worthless? By definition, they do—but…

Of course, FDIC is backed _informally_ by the Fed. It’s the same F, after all! So actually, when you “deposit” “$500,000” with Wells Fargo, you are actually trading 500,000 FRNs for 500,000 WF-FRNs, 500,000 WF-FDIC-CDS, and 500,000 _FDIC-iCDS_. Whose value exactly equals 500,000 FRNs! And the world is saved. “Press F to pay respects.”

But if we are to take Secretary Yellen at her word, an FDIC-iCDS (a rock-solid, good as gold, informal security) is worth more than a BO-iCDS (which depends on what the Secretary had for breakfast). Therefore, logic suggests that the people of Oklahoma should move their “deposits” out of the Bank of Oklahoma and into Wells Fargo.

Senator Lankford, obviously well-briefed, asks exactly that question:

> What is your plan to keep large depositors from moving their deposits out of community banks into the big banks? I’m concerned you’re about to accelerate that by encouraging anyone who has a large deposit in a community bank to say we’re not going to make you whole, but if you go to one of our preferred banks we are going to make you whole.

Ms. Yellen’s extremely reassuring response:

> Um, look, that is certainly not something we are encouraging… we felt that there was a serious risk of contagion that could have brought down and triggered runs on many banks, um, and that something given that our judgment is that the banking system is safe and sound, um, depositors should have confidence in the system…

Extremely confidence-inducing indeed…

But once we have described this bizarre pyramid of formal and informal securities, what is the way forward? As Hernando de Soto would tell you, the solution to informal Third World property rights is one of two options: cancel, or formalize.

It’s not a choice. _Canceling_ all these iCDS—as a strict, autistic libertarian would want—means zombies eating human flesh in the streets. _Formalizing_ them means—things keep working the way they work now. The iCDS become CDS. The FDIC “insures” all the “deposits” “in” the Bank of Oklahoma. And the Fed formally “insures” the FDIC.

But when you look at all of these nominally “independent” corporations giving free securities to each other, like Christmas just went out of style, it still just feels wrong. What is a simpler way to keep things working the way they work now?

Well, we could just acknowledge that not only is the Fed is a government agency, and FDIC is a government agency, but the Bank of Oklahoma is _also_ a government agency. This explains why the government (a) gives it free securities and (b) tells it what to do.

If we consolidate the _whole banking system_ onto USG’s balance sheet, the whole system makes perfect sense. Instead of a BO-FRN plus a FDIC-BO-CDS plus an FDIC-iCDS, you just have an FRN. Which is how you think of a dollar “in” the bank—as a dollar.

As for the loans that the Bank of Oklahoma makes—they are just _government loans_. The government of the US, like the government of the USSR, is a state lender. This is why the government of the US has strict regulatory principles that defines who does and does not deserve a bank loan.

In the new _consolidated_ system, lending is no longer a private-sector activity—you simply apply to the government for a loan, which uses standard criteria to deny or approve you. Which is exactly how it works when you buy a house right now. The government could even incentivize good lending through a sales-commission system, replicating the profit motive of existing banks—to the extent that regulators have left them with any lending discretion whatsoever. Which isn’t much.

This is exactly why the Fed did _not_ approve (stop snickering) of TNB, which proposed to pay 4% interest on checking accounts by depositing the money directly in the Fed, which pays 4.65% on its reserves—and not making any loans at all. While customers would love this product, and it would be risk-free without any FDIC “insurance,” TNB would not fulfill the _actual_ purpose of banking—to _gavage_ the economy with debt, like a _foie-gras_ goose. Because if the borrowing stops, the whole system explodes.

_This_ is the infrastructure which Patrick McKenzie calls “so good you’ll hopefully never even have to realize it is there.” Well… uh… we, uh… realize it is there. Good times!

But where are we now? What has actually been done? What is going to happen?

I was puzzled in 2022—somewhat to my financial detriment—when the Fed jacked up rates from 0% to near 5%, in order to generate the fabled “soft landing” and [whip inflation now](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Whip_inflation_now). What I expected was a “hard landing.” What we got was neither—we got _no landing at all_.

At a very abstract level, when you pressure a system in some direction and don’t get the expected response in that direction, it suggests that _the pressure has no outlet_. Put a frozen palak paneer in the microwave for two minutes, after sticking a fork in the film—steam will escape. Don’t pierce the film—_no_ steam will escape. After _three_ minutes… there will be spinach all over the inside of your microwave.

What the absence of a landing suggests is that there are only two kinds of landing: no landing, or a _crash_ landing. One historically recurrent tendency in financial regulation is to “stabilize” systems by disconnecting market signals, removing pressure’s outlet.

Now, this _can_ actually work. Make a “piercing-free” palak paneer with a film that is three times as thick as usual: it will take _four_ minutes to explode, then blow the door of your microwave. But if your Indian food is packed in some kind of plastic _pressure vessel_, you can microwave it for _fifteen_ minutes, converting all the water to steam, and nothing will happen. Allow five minutes to cool and open very carefully.

Which is it this time? If you know… you can profit…

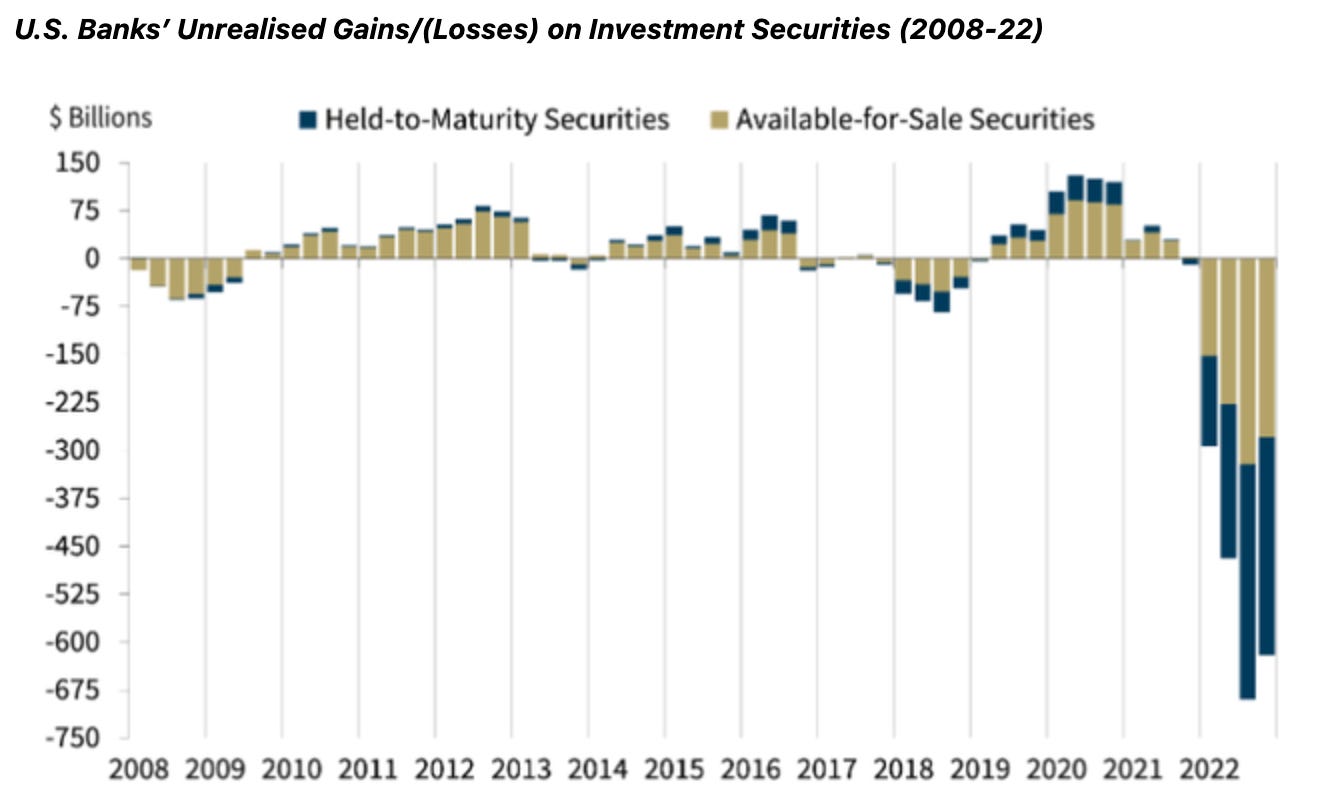

If you read the McKenzie essay, or if you have a basic grasp of finance, you realize that raising short-term interest rates murders the price of long-term loans. Most people now have seen this infamous chart:

[

](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F399d096e-bbc0-466b-beec-c84809bd8607_1328x798.png)

This alone is very different from 2008, because in 2008 what impaired the value of bank assets was repayment risk. This is not risk. This is just interest-rate math.

A bond represents a payment stream whose present value can be calculated as a function of a yield curve, or interest rate across duration. If you know the interest rate and the probability that the bond will fail, you know the price of the bond. This is just an equation with three variables—if you know any two, you know the other one.

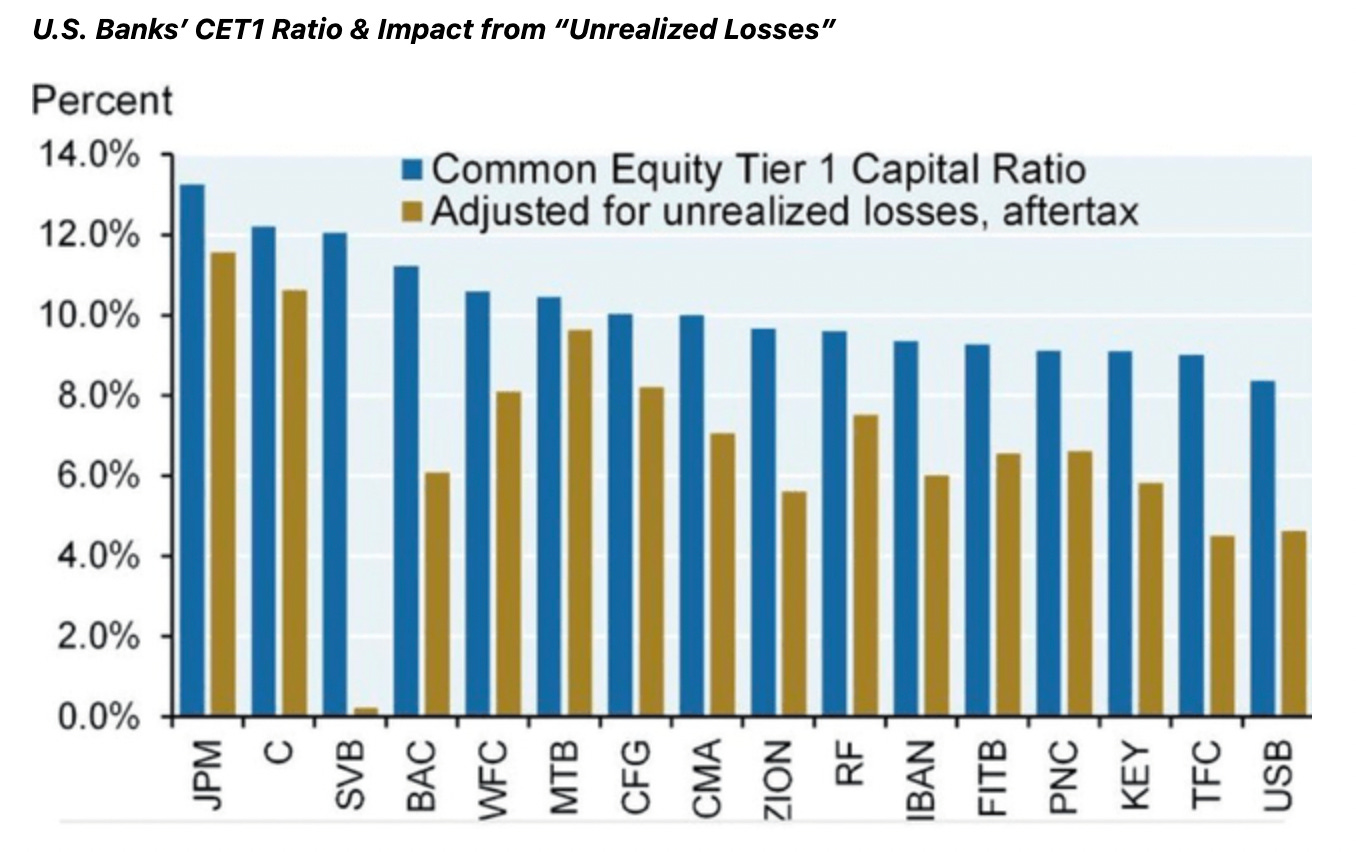

The film on the palak paneer is that banks, for Byzantine historical accounting reasons, get to account for some of their assets as _more than they are actually worth_.

These are the “hold-to-maturity” assets which the bank “intends” to not sell—ignoring the reality that the bank’s “deposits,” zero-term loans from the customer to the bank, are promises to redeem _immediately_. The whole theory of bank solvency is that a solvent bank, regardless of its “intent,” can make all its liabilities good by selling all its assets if all its customers decide to not renew their zero-term loans.

Bank of America, for instance, has lost almost half its equity—over $100 billion—in these unrealized losses, which are reported only as a footnote and do not count.

[

](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F10d921dd-4e82-439f-a08c-3835986ab061_1356x852.png)

[Here is a case](https://seekingalpha.com/article/4587491-bank-of-america-stock-ignore-114-billion-unrealized-losses) for why you should buy BAC shares anyway. But think about a couple of facts before you make this call.

_First_, the Fed’s [bandaid](https://www.barrons.com/articles/bank-term-funding-program-btfp-bedb0367) for the SVB crisis is to _lend_ money against these impaired assets _at their original cost, which has nothing to do with present reality_. Ok fine lol. So when the “depositor” fails to renew the zero-term loan that is a “deposit,” instead of having to sell these assets and find out what they are actually worth, the bank can essentially _pawn_ them with the Fed.

Of course, if you pawn your jewelry, you don’t have to come back and get it—if you don’t repay the loan, the pawnshop bought it. The BTLP does not work this way. This is not the 2008 [TARP](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Troubled_Asset_Relief_Program), which _bought_ the financial garbage from the housing bubble. If banks can’t return their BTLP loans, and the loans are not renewed, the banks fail.

What this means is that the Fed does not believe these banks have a solvency problem. Or if it does—it doesn’t care. And indeed, it doesn’t need to care.

Suppose a bank had no assets except Beanie Babies—but the Fed was willing to lend, with said Beanie Babies as collateral, an amount equivalent to its deposits. Nothing is wrong! If all the depositors leave, the Fed just becomes the sole “depositor.”

When we realize that all banks are Fed branches and the Fed can print money, just as Microsoft can print Microsoft shares, we realize that in a fiat currency system, there is _never any objective reason to have a bank crisis_. All such crises are bureaucratic in nature. Any decision to close a bank, haircut depositors, or even zero out bank shareholders, is a completely discretionary bureaucratic decision by the Fed.

And yet: even when pawned to the Fed, these assets still belong to the bank. They still appear on the bank’s balance sheet. Pricing them at what they used to be worth is still a _lie_—and someone needs to own this lie. And bureaucrats hate to own things.

_Second_, the solvency aspect of the crisis is generally understated—because we are looking at only those assets with a direct bureaucratic impact. Banks do not just buy bonds. Banks make loans—they have a loan book.

So there are really _three_ kinds of assets on a bank’s books: marketable securities held at market value (“AFS,” available for sale); marketable securities held at fantasy value (“HTM,” hold to maturity), and unmarketable, bespoke, custom _loans_.

These loans are long-term loans—so their fundamental value is just as damaged by short-term interest rate rises. But it is harder to price them. Their prices are invisible. So the losses from interest-rate damage are also invisible. They are still there, though—and again, someone needs to take ownership of that.

_Third_, in an environment with 5% interest rates, everyone sane has a reason to stop subsidizing banks by holding zero-rate “deposits.” It is easy to earn 4% on a money-market fund which invests in short-term Treasuries and other bills—it is just slightly more inconvenient to spend this money.

The market makes all these “deposits” want to go away. Liquidity hides solvency issues—as the water level of deposits falls, we find out who is swimming naked. Bureaucrats hate to swim naked.

Since banks are Fed branches, nothing fundamentally is wrong with all the banks being insolvent. They could all hold nothing but Beanie Babies. But some bureaucrat would have to take responsibility for issuing Federal Reserve Notes backed by Beanie Babies—and no bureaucrat wants to do that.

Do you know these bureaucracies well enough to know what the bureaucrats will do? Then you can make money. Do you _not_ know? Leave the betting to those who know—and confine yourself to laughing at this insane machine we inherited from the past.