在 RustForLinux 组织中,存在 13 个仓库,其中除去 linux 主仓库外,剩下的部分可以分成为三个组别,一个就是当前仍处于维护期的工具集,Rust-For-Linux 持续化集成相关的内容,一些代码示例仓库,以及几个已经很久没有进行维护的基于 nix 实现的编译包。

## 当前主要工具集

### pinned-init

> 库使用就地构造函数安全且易出错地初始化固定结构。

> 它还允许对 **大结构体** 进行 **就地初始化**,以避免产生堆栈溢出。

与之有一定关联的还有 std::pin, pin-init 两个库。**pin-project?**

##### std::pin

> std::pin 主要用于异步编程以及处理自引用结构体上。

> 处于一般性考量,rust 中的大多数类型都自动实现了 `UnPin Trait` ,被声明为类型的值可以在内存中安全的被移动。

> 标准库所提供的 `Pin` 是一个结构,他包裹了一个指针,通过避免直接获取内部 item 的 &mut T,只能使用 mut 借口,确保了指针所指向的元素不会被移动,也不会因为 `mem::swap` 而导致在多线程情况下的悬垂指针。

> 但不是所有的 item 都可以被 `Pin`,对于没有实现 `!UnPin trait` 的 item 而言,就算采用了 `Pin` 结构体对之进行包裹,同样没法保证其值不可移动,就比如说 `Pin<&mut u8>`。

```rust=

pub struct Pin<P> {

pointer: P,

}

```

*注:可使用`_marker: PhantomPinned,`使自定义类型转化成为 `!UnPin` 类型。在实现 `!UnPin trait` 之后,再将这个结构体的值固定在栈上就成为了不安全的行为,此时只能将数据保存在堆上面

##### pin-project

> 提供了一个宏,允许创建一个涵盖部分值固定的结构体,这个结构体通过对于库的简单包装,实现了更加人体工学的对 pin 的调用。

##### Pin-init

> 据称提供了与 pinned-init 类似的功能,可以与 pin-project 一起使用。

##### Pinned-init

> 由 RustForLinux 提供,提供了 pin_init! 宏以方便对于结构体的原地初始化,并且固定其地址,被直接配置在 RustForLinux next 分支,目前主要用作于与 Sync,相关的几个结构体的初始化。(safely and fallibly initialize pinned structs using in-place constructors.)

一个简单的例子,说明了简单结构体初始化的差异(使用pinned-init和std::pin)

```rust=

#![allow(dead_code, unused_imports, unused_variables, unused_mut, unsafe_code, unused)]

use pinned_init::*;

use core::marker::PhantomPinned;

use std::{pin::Pin, fmt::{self, Formatter}, ptr};

struct Foo {

x: usize,

y: Pin<Box<i32>>,

}

impl Foo {

fn new(x: usize, y: i32) -> Self {

Self {

x,

y: unsafe { Pin::new_unchecked(Box::new(y)) },

}

}

fn get_x(self) -> usize { self.x }

fn get_y(self) -> i32 { *self.y }

fn set_x(&self, num: usize) {

unsafe {

let x = &mut *(self as *const _ as *mut Foo);

x.x = num;

}

}

fn set_y(&mut self, num: i32) {

let mut y = Pin::as_mut(&mut self.y);

*y = num;

// unsafe {

// let x = &mut *(self as *const _ as *mut Foo);

// *x.y = num;

// }

}

fn print_location(&self) {

format!("{:?} ({:?}, <{:?}:{:?}>)",

&self as *const _,

&self.x as *const _,

&self.y as *const _,

Pin::get_ref(self.y.as_ref()) as *const _,

);

}

}

impl fmt::Debug for Foo {

fn fmt(&self, f: &mut fmt::Formatter) -> fmt::Result {

f.debug_struct("Foo")

.field("x", &self.x)

.field("y", &self.y)

.field("location",

&format!("struct:{:?}| x:{:?}| Box<y>:{:?}| y:{:?}",

&self as *const _,

&self.x as *const _,

&self.y as *const _,

Pin::get_ref(self.y.as_ref()) as *const _,

))

.finish()

}

}

fn main() {

println!("hello, world!");

let mut foo = Box::pin_init(Foo::new(1, 2)).unwrap();

println!("{:?}", foo);

foo.set_x(12);

println!("{:?}", foo);

foo.set_y(12);

println!("{:?}", foo);

func(foo);

}

fn func(foo: Pin<Box<Foo>>) {

println!("{:?}", foo);

funb(foo);

}

fn funb(foo: Pin<Box<Foo>>) {

println!("{:?}", foo);

}

```

```rust=

#![allow(dead_code, unused_imports, unused_variables, unused_mut, unsafe_code, unused)]

// Ref: RustForLinux/linux/rust/kernel/sync/lock.rs

use core::marker::PhantomPinned;

use std::{pin::Pin, fmt::{self, Formatter}, ptr};

struct Foo {

x: usize,

y: Pin<Box<i32>>,

}

impl Foo {

fn new(x: usize, y: i32) -> Self {

Self {

x,

y: unsafe { Pin::new_unchecked(Box::new(y)) },

}

}

fn get_x(self) -> usize { self.x }

fn get_y(self) -> i32 { *self.y }

fn set_x(&self, num: usize) {

unsafe {

let x = &mut *(self as *const _ as *mut Foo);

x.x = num;

}

}

fn set_y(&mut self, num: i32) {

let mut y = Pin::as_mut(&mut self.y);

*y = num;

// unsafe {

// let x = &mut *(self as *const _ as *mut Foo);

// *x.y = num;

// }

}

fn print_location(&self) {

format!("{:?} ({:?}, <{:?}:{:?}>)",

&self as *const _,

&self.x as *const _,

&self.y as *const _,

Pin::get_ref(self.y.as_ref()) as *const _,

);

}

}

impl fmt::Debug for Foo {

fn fmt(&self, f: &mut fmt::Formatter) -> fmt::Result {

f.debug_struct("Foo")

.field("x", &self.x)

.field("y", &self.y)

.field("location",

&format!("struct:{:?}| x:{:?}| Box<y>:{:?}| y:{:?}",

&self as *const _,

&self.x as *const _,

&self.y as *const _,

Pin::get_ref(self.y.as_ref()) as *const _,

))

.finish()

}

}

fn main() {

println!("hello, world!");

let mut foo = Foo::new(1, 2);

println!("{:?}", foo);

foo.set_x(12);

println!("{:?}", foo);

foo.set_y(12);

println!("{:?}", foo);

func(foo);

}

fn func(foo: Foo) {

println!("{:?}", foo);

funb(foo);

}

fn funb(foo: Foo) {

println!("{:?}", foo);

}

```

运行结果:

```bash

$ cargo run --example pin1.rs (可能实现上存在问题)

Foo { x: 1, y: 2, location: "struct:0x7ffd332e2a88| x:0x7ffd332e2dd8| Box<y>:0x7ffd332e2dd0| y:0x55811bfcbba0" }

Foo { x: 12, y: 2, location: "struct:0x7ffd332e2a88| x:0x7ffd332e2dd8| Box<y>:0x7ffd332e2dd0| y:0x55811bfcbba0" }

Foo { x: 12, y: 12, location: "struct:0x7ffd332e2a88| x:0x7ffd332e2dd8| Box<y>:0x7ffd332e2dd0| y:0x55811bfcbba0" }

Foo { x: 12, y: 12, location: "struct:0x7ffd332e29e8| x:0x7ffd332e2cd8| Box<y>:0x7ffd332e2cd0| y:0x55811bfcbba0" }

Foo { x: 12, y: 12, location: "struct:0x7ffd332e2948| x:0x7ffd332e2c40| Box<y>:0x7ffd332e2c38| y:0x55811bfcbba0" }

```

```bash

$ cargo run --example pinned-init (使用pinned-init库)

Foo { x: 1, y: 2, location: "struct:0x7ffdeb342e98| x:0x55f310da1bc8| Box<y>:0x55f310da1bc0| y:0x55f310da1ba0" }

Foo { x: 12, y: 2, location: "struct:0x7ffdeb342e98| x:0x55f310da1bc8| Box<y>:0x55f310da1bc0| y:0x55f310da1ba0" }

Foo { x: 12, y: 12, location: "struct:0x7ffdeb342e98| x:0x55f310da1bc8| Box<y>:0x55f310da1bc0| y:0x55f310da1ba0" }

Foo { x: 12, y: 12, location: "struct:0x7ffdeb342df8| x:0x55f310da1bc8| Box<y>:0x55f310da1bc0| y:0x55f310da1ba0" }

Foo { x: 12, y: 12, location: "struct:0x7ffdeb342d68| x:0x55f310da1bc8| Box<y>:0x55f310da1bc0| y:0x55f310da1ba0" }

```

```bash

$ cargo run --example normal1 (一般情况下的结果)

Foo { x: 1, y: 2, location: "struct:0x7ffc02fcb868| x:0x7ffc02fcbb98| Box<y>:0x7ffc02fcbb90| y:0x558c63448ba0" }

Foo { x: 12, y: 2, location: "struct:0x7ffc02fcb868| x:0x7ffc02fcbb98| Box<y>:0x7ffc02fcbb90| y:0x558c63448ba0" }

Foo { x: 12, y: 12, location: "struct:0x7ffc02fcb868| x:0x7ffc02fcbb98| Box<y>:0x7ffc02fcbb90| y:0x558c63448ba0" }

Foo { x: 12, y: 12, location: "struct:0x7ffc02fcb7c8| x:0x7ffc02fcba98| Box<y>:0x7ffc02fcba90| y:0x558c63448ba0" }

Foo { x: 12, y: 12, location: "struct:0x7ffc02fcb728| x:0x7ffc02fcba00| Box<y>:0x7ffc02fcb9f8| y:0x558c63448ba0" }

```

#### Reference

- [Pin, Unpin, and why Rust needs them](https://blog.cloudflare.com/pin-and-unpin-in-rust/)

- [Rust圣经::定海神针 Pin 和 Unpin](https://course.rs/advance/async/pin-unpin.html)

- [RustForLinux::rust-next](https://github.com/Rust-for-Linux/linux/tree/rust-next)

### Klint Rust Tools

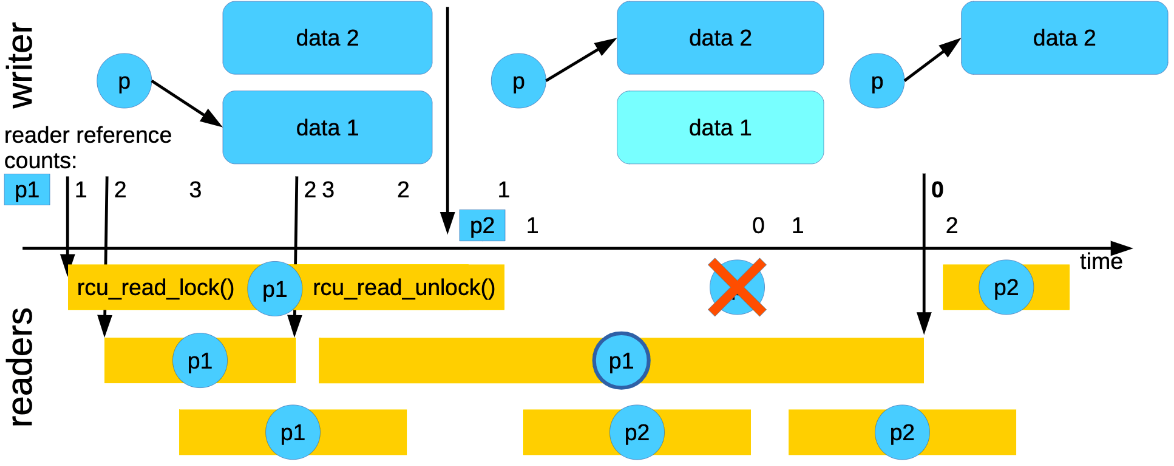

在 linux kernel 中存在一种相对特殊的机制,即 [RCU](http://hackfoldr.org/linux/https%253A%252F%252Fhackmd.io%252Fs%252FH19V4eyfV) (Read Copy Update), 这种机制主要被用在提供对于共享数据结构的搞笑读取访问,允许多个 Reader 在不加锁的情况下访问共享数据结构。这种特殊的机制,在不生成锁的情况下,利用了处理器的机制,在其他核心都进行了一次上下文切换之后继续运行后面的指令。

图1:C 语言 RCU 写法

```c

void foo_read(void) {

rcu_read_lock();

foo *fp = global_foo;

if (fp)

do_something(fp->a, fp->b, fp->c);

rcu_read_unlock();

}

void foo_update(foo *new_fp) {

spin_lock(&foo_mutex);

foo *old_fp = global_foo;

global_foo = new_fp;

spin_unlock(&foo_mutex);

synchronize_rcu();

kfree(old_fp);

}

```

图2:宽限期

上述机制最主要的问题是,在读取端获取到对应的数据结构指针之后,不允许出现 sleep 或者其他因素导致上下文被切换。

一旦在读取端中出现上下文切换的情况,`synchronize_rcu()`提前返回,可能导致内存在`rcu_read_unlock()`之前被释放。同时,在释放之前由于读取段尚未完成对于当前获取的数据结构的操作,因而产生悬垂引用。 *或者说死锁?*

在 Rust 中,因为 Rust 使用 RAII,而非通过单独的 lock and unlock 源语来调用同步源语,通过返回一个具有 Guard 的锁定函数来实现锁定,通过超过生命周期 Drop 来实现解锁。

```rust=

struct RcuProtectedBox<T> {

write_mutex: Mutex<()>,

ptr: UnsafeCell<*const T>,

}

impl<T> RcuProtectedBox<T> {

fn read<'a>(&'a self, guard: &'a RcuReadGuard) -> &'a T {

// SAFETY: We can deref because `guard` ensures we are protected by RCU read lock

let ptr = unsafe { rcu_dereference!(*self.ptr.get()) };

// SAFETY: The lifetime is the shorter of `self` and `guard`, so it can only be used until RCU read unlock.

unsafe { &*ptr }

}

fn write(&self, p: Box<T>) -> Box<T> {

let g = self.write_mutex.lock();

let old_ptr;

// SAFETY: We can deref and assign because we are the only writer.

unsafe {

old_ptr = rcu_dereference!(*self.ptr.get());

rcu_assign_pointer!(*self.ptr.get(), Box::into_raw(p));

}

drop(g);

synchronize_rcu();

// SAFETY: We now have exclusive ownership of this pointer as `synchronize_rcu` ensures that all reader that can read this pointer has ended.

unsafe { Box::from_raw(old_ptr) }

}

}

```

在当前阶段中,使用 Rust 提供 RCU 抽象的尝试实际上面临一些问题,比如说使用 unsafe 关键词包裹所有的抽象,或者是通过强制占用计数以及原子上下文检查实现这个效果。但是目前来看,内核的 Rust API 抽象中不包含有关于这种情况的保护,这也就带来了一个问题,如果在编译的时候如果禁用抢占计数跟踪,可能导致内存释放后被仍使用的情况。

因为我们不能在 Rust API 的抽象中处理睡眠亦或是强制使用运行时检查,我们提供了 klint 工具来帮助我们检查可能导致这种情况出现的因素。

klint 工具通过跟踪抢占计数来检查可能出现的上下文违规,

- #[klint::preempt_count] 注释属性

- #[klint::drop_preempt_count] 当删除结构的时候注释行为

```rust=

#[klint::drop_preempt_count(adjust = -1, expect = 1.., unchecked)]

struct RcuReadGuard { /* ... */ }

#[klint::preempt_count(adjust = 1, expect = 0.., unchecked)]

pub fn rcu_read_lock() -> RcuReadGuard { /* ... */ }

```

#TODO 尚未完成代码实现相关的分析内容

### Reference

- [Experimental PR for introducing klint](https://github.com/Rust-for-Linux/linux/pull/958)

- [Can Rust Code Own RCU](https://paulmck.livejournal.com/64209.html)

- [Klint: Compile-time Detection of Atomic Context Violations for Kernel Rust Code](https://www.memorysafety.org/blog/gary-guo-klint-rust-tools/)

## Rust-For-Linux 持续化集成相关的内容

> 主要包含 [ci](https://github.com/Rust-for-Linux/ci), [docs](https://github.com/Rust-for-Linux/docs), [rust](https://github.com/Rust-for-Linux/rust),[binutils-gdb](https://github.com/Rust-for-Linux/binutils-gdb), [ci-bin](https://github.com/Rust-for-Linux/ci-bin) 几个仓库,目前来说最有可能有帮助的地方在于提供了一个能保证编译的 Dockerfile,方便我们进行编译

## 基于 nix 实现的编译包

> 主要包含 [nix](https://github.com/Rust-for-Linux/nix),[nixpkgs](https://github.com/Rust-for-Linux/nixpkgs)两个包。

> 其中 nixpkgs 是一个公有的软件包仓库,类似于 AUR。nix 则是之前他们提供的一个基于 Nix 的 Kernel 编译工具,目前来看由于长期没有对于代码仓库进行维护,无法使用现有仓库编译 kernel。

## 一些代码示例仓库

> 主要包含 [pahole-rust-cases](https://github.com/Rust-for-Linux/pahole-rust-cases), [rust-out-of-tree-module](https://github.com/Rust-for-Linux/rust-out-of-tree-module) 俩个仓库,基本上没有什么实际的内容。

----

----

----

# 草稿

~~

目前,主要有以下几个仓库相对来说更加值得研究,klint, pinned-init, rust-out-of-tree-module, binutils-gdb, rust

klint:

Compile-time Detection of Atomic Context Violations for Kernel Rust Code

https://www.memorysafety.org/blog/gary-guo-klint-rust-tools/

Rust 中代码的数据安全性是可以在相当程度上得到保证的,安全区代码不应该导致空指针引用或者数据竞争的出现,但是在 Linux 内核中深度使用的 RCU (read copy update) 同步技术,通过对于多个读取器访问共享数据结构而不加锁,但是,从RCU读取侧临界区段访问的这个数据结构将保持活动并且将不会被解除分配,直到可访问它的所有读取侧临界区段已经完成。

### C 中的实现

```c

/* CPU 0 */ /* CPU 1 */

rcu_read_lock();

ptr = rcu_dereference(v); old_ptr = rcu_dereference(v);

/* use ptr */ rcu_assign_pointer(v, new_ptr);

synchronize_rcu();

/* waiting for RCU read to finish */

rcu_read_unlock();

/* synchronize_rcu() returns */

/* destruct and free old_ptr */

```

但是根据分析 **目前尚未获得**

`rcu_read_lock` 会编译成为 `asm volatile("":::"memory")` (生成了一个内联汇编屏障以避免优化导致顺序出现错误),但是没有产生任何其他的代码,他以另外的一种方式实现了 `synchronize_rcu` 的效果,使得他在所有 CPU 核心至少经历一次上下文切换之后返回。*(名义上他能保证正在执行的所有RCU临界区域完成,但是实际上他没生成代码,是通过确保在这个部分中所有CPU核心都切换一次上下文实现的)*

其可靠性主要依赖于代码不能在 RCU读端临界区内休眠,如果存在这种休眠的情况,会导致`synchronize_rcu` 提前返回(切换上下文)

### Rust 中的实现

Rust 中所提供的 lock, unlock 不是对于同步源语的简单调用,而是使用 RAII 完成的(当资源离开其作用范围时则调用析构函数释放资源)

~~

Sign in with Wallet

Sign in with Wallet

Sign in with Wallet

Sign in with Wallet