# Intent-based Actuation

[TOC]

For most of our services, we made infrastructure changes using hand-crafted procedural workflows:` push x, then y`; *perform the odd change manually*.

But teams were commonly managing tens of services apiece, and each service had many jobs, databases, configurations, and custom management procedures. The existing solutions were not scaling for two main reasons:

- **Infrastructure** configurations and APIs were heterogeneous and hard to connect together— for example, different services had different configuration languages, levels of abstraction, storage and push mechanisms, etc. As a result, infrastructure was inconsistent, and establishing common change management was difficult.

- **Production** change management was a brittle process, with little understanding of the interactions between changes. Automated turnups were an exercise in frustration.

### NxM problem

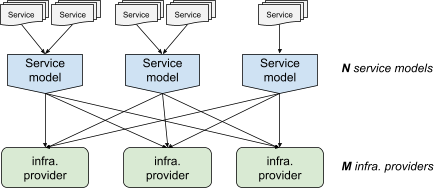

If you're dealing with multiple service models and multiple infrastructure providers,** you have to maintain integrations between N service models and M infrastructure providers**. This integration includes both generating each provider's specific configuration and also deploying it— a process which can vary significantly across providers.

NxM problem, as illustrated in Figure 1.

## DAG vs FSM

Using a DAG to represent a workflow had a few limitations including:

> 1. Expressing different transition rules for different steps. Rules applied to all steps. Special rules for specific types of steps was difficult to implement.

> 2. End state determination was difficult. End state is the state where the workflow can no longer be run. This can happen if the various steps end up in a state where there is no way to move them forward in the DAG.

With these changes, each step is a state machine with its own states, actions and transition rules. A workflow is achieved by guarding actions on state machines with pre-conditions, which state the states *other* machines need to be in. An action can be performed when the other machines are in the states as specified in the pre-conditions. With this, one machine can be run only if its predecessors have successfully run, thereby achieving a workflow. However, since such pre-conditions can be specified for *any* state transition, arbitrary steps can be run based on transitions (e.g., if a step fails, a clean-up step can be run). Such flexibility with a DAG would be much more complicated.

End state determination is always deterministic. The end state is when all the machines have no possible actions, thereby, no state transitions are available. This simplifies workflow monitoring and management.

## Workflow vs Intent Management Models

In a workflow-oriented production management model, a large part of the state of production exists only in production. For example, your frontend runs version X because a few days ago, you started a rollout of this specific version.

In contrast, declarative production means that you write the intent of your production state—that your production is supposed to run version X—in a configuration file or a database.

The production state is now derived from this intent. Paired with continuous enforcement, this ensures that production matches what people expect.

In our experience, the notion of intent is often seen as intuitive and rarely causes confusion. However, maintaining intent can be difficult, and require extensive logic. Prodspec (which we discuss further in the following section) is our solution to this problem of modeling and generation.

Intent-based actuation required a large shift in perception of how production was meant to be modified. To phrase the problem in the "pet vs cattle" metaphor: previously, we treated workflows like pets: we kept a running inventory of individual workflows, hand-tuned them, and interacted with them individually. Intent-based actuation instead uses an enforcement system that treats production assets as cattle: special cases become rare, and scaling becomes much easier. To this end, we created a continuous enforcement system called Annealing (described below).

## Declarative Intent Data Model

The declarative intent is modeled through a few abstractions:

- Assets: Each asset describes a specific aspect of production.

- Partitions: Organize the assets in administrative domains.

- Incarnations: Represent snapshots of partitions at a given point in time.

## Assets

Assets are the core of the Declarative Intent data model. An *asset* contains the configuration of one specific resource of a given infrastructure provider. For example, an asset can represent the resources in a given cluster or instructions for how to configure a specific job.

An asset is a very generic abstraction with the following structure:

- A string identifier, simply called "asset ID".

- A payload.

- Zero or more addons.

The payloads and the addons are arbitrary protobuf messages. The type of the payload defines the type of the asset.

The addons make it possible to add arbitrary metadata to an asset, no matter its type. Addons are particularly useful for cross-cutting concerns. For example, the common "impacted cluster" addon gives an idea of the area of influence of an asset— if this asset is unhealthy, will it cause an outage just for one cluster, or for the service globally? Addons also provide space for user-specific data without polluting the payload definition.

Assets are often less than 1kb of data and typically less than 10kb, while we enforce a strict maximum of 150kb. The goal behind this restriction is to make assets easy to consume. This way, tooling can load assets in memory without having to worry about the cost of doing so. Our approach is inspired by Entity-Component systems.

The content of an asset provides sufficient information to construct the full state of the modeled resource. Specifically, it should be possible to recreate the production state without having to look at the current state of production—this is a one-way process.

### Partitions

Assets are grouped into administrative boundaries called partitions. Partitions typically match 1:1 with a service. However, there are exceptions. For example, a given user might want to have one partition for its QA environment and another for its Prod environment. Another user might use the same partition for both its QA and Prod environments. In practice, we leverage the notion of partitions to simplify many administrative aspects. To name a few aspects:

- Content generation occurs per partition.

- Many ACLs are set per partition.

- Enforcement is fully isolated per partition.

- An asset ID must be unique within a partition.

Assets within partitions are not structured, but instead are organized in a flat unordered list. Over the years, we've found that there is really no one-size-fits-all approach for structuring service assets. However, we don't entirely forgo structure: instead of structuring the assets themselves, asset fields can contain references to other assets. This makes it possible to create multiple hierarchies on the same assets. For example, the cluster hierarchy is different from the dependency hierarchy. Those reference fields are explicitly marked as such, allowing programmatic discovery.

## Incarnations

We regularly snapshot the content of a partition. Those snapshots are called incarnations, and each incarnation has a unique ID. Incarnations are the only way to access Prodspec data. Besides being a natural consequence of the generation logic (see Generation Pipeline), the incarnation model provides immutability and consistency.

Immutability ensures that all actors accessing Prodspec make decisions based on the same data. For example, if a server is responsible for validating that an asset is safe to push, the server actuating the push is guaranteed to work on the same data. Caching becomes trivial to get right, and it is possible to inspect the information used for automated decisions after the fact.

Consistency is important because we rarely look up assets in isolation. An asset might need to reference other assets to assemble a full configuration. If the content of those assets comes from different points in time, you might end up with broken assumptions. Imagine that in the Shakespeare service, the capacity in one cluster is reduced. This change requires decreasing both the size of the frontend job in that cluster and the corresponding load balancer configuration. Without some form of consistency, Annealing would be at risk of reducing the size of the job before updating the load balancer configuration, leading to an overload.

**Generators**: transform sources of truth into assets. Some generators consume the output of another generator instead of a SoT, forming a pipeline. For example, one of our generators adds to each asset an addon describing the "physical cluster" of that asset by extrapolating the payload content.

**Validation**: We run each generated incarnation through an extensive series of validators. Most validators verify self consistency of the incarnation, while some cross-check the content with external databases. It's extremely important to have a good suite of validators—corruption is a very common source of configuration issues, and validators can be quite effective at detecting corruption and preventing bad configuration from reaching production. We almost always add multiple validators when adding new asset types or addons.

**Storage**: Once an incarnation is validated, we store the result in Spanner. While a specific incarnation is rarely used for long, it's valuable to keep the results around for debugging problems after the fact.

**Serving**: Stored incarnations are accessed through a query server. Consumers can request the latest incarnation, a specific incarnation, or a few other variations. They can also filter out the assets they want to see, which is useful when dealing with incarnations that have thousands of assets. We use Spanner indexing to filter data relatively quickly. The filtering language isn't made to be precise: its goal is to reduce the amount of data to manipulate. More complex filtering should be performed on the client side.

## Incarnation States

The loop does not pick up each incarnation one after the other, and there is no guarantee that each individual incarnation will be enforced. Instead, each iteration uses the latest incarnation. This approach avoids getting stuck on a broken incarnation. Instead, there's an opportunity to fix the intent, which will be automatically picked up. As a consequence, if a specific intermediate state must be reflected in production, you must wait for that state to be enforced before updating the intent further.

Each asset is independent, and the loop runs independently for each asset. However, we don't push assets at will—this is where checks are fundamental. We use checks to delay—not reject—changes to production.

Annealing has visibility and control across the whole service it enforces. This gives Annealing a unique centralized point of view, allowing checks to easily enforce invariants across production. This makes checks often conceptually simple, but powerful. For example:

### Checks

The calendar check prevents pushes on weekends and holidays.

The monitoring check verifies that no alert is currently firing, or that the system is not currently overloaded.

The capacity check blocks pushes that would reduce the serving capacity below the maximum recent usage.

The dependency solver orders concurrent changes to ensure the right order of execution.

## Incarnation intents

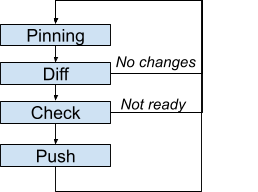

- Pinning: Determines which incarnation to use as intent.

- Diff: If no difference exists between intent and production, the loop iteration stops.

- Check: When a push is needed, verifies whether the push can proceed now. Otherwise, the loop iteration stops.

- Push: Updates the infrastructure based on the intent.

-

The loop does not pick up each incarnation one after the other, and there is no guarantee that each individual incarnation will be enforced. Instead, each iteration uses the latest incarnation. This approach avoids getting stuck on a broken incarnation. Instead, there's an opportunity to fix the intent, which will be automatically picked up. As a consequence, if a specific intermediate state must be reflected in production, you must wait for that state to be enforced before updating the intent further.

Each asset is independent, and the loop runs independently for each asset. However, we don't push assets at will—this is where checks are fundamental. We use checks to delay—not reject—changes to production.

Annealing has visibility and control across the whole service it enforces. This gives Annealing a unique centralized point of view, allowing checks to easily enforce invariants across production. This makes checks often conceptually simple, but powerful. For example:

The calendar check prevents pushes on weekends and holidays.

The monitoring check verifies that no alert is currently firing, or that the system is not currently overloaded.

The capacity check blocks pushes that would reduce the serving capacity below the maximum recent usage.

The dependency solver orders concurrent changes to ensure the right order of execution.

## Dependency Solver

The dependency solver is the first check. It makes sure that assets are pushed in the correct order when resized. Consider Figure 6 in terms of the Shakespeare service: when reducing the footprint in a cluster, you usually want to update the load balancer configuration to reduce the maximum capacity served by that cluster before reducing the replica count of the frontend— that way, you do not end up with a frontend that's unable to cope with the load sent to it. The solver check allows you to update the capacity of both the load balancer and the frontend in one change, while Annealing will push these changes in the safe order.

The dependency solver check uses the following logic:

A request to push an asset A is made, as described in previous sections.

Enforcer calls the check plugins, including the solver.

The solver checks the diff of asset A. If the diff indicates a change not impacting capacity, the check passes.

If the check finds a change in capacity, the solver queries the dependencies of the asset. Those dependencies are explicitly listed in Prodspec with an addon and are often automatically generated in the Prodspec generation pipeline.

The solver requests a diff against production for each dependency B.

If the diff on asset B indicates that it requires a capacity change for the service to operate properly after asset A is pushed, then the push of A is blocked until the diff on asset B disappears. Otherwise, asset A can proceed and be pushed.

The exact logic to determine whether a push can proceed can be complex, but also makes this pattern generic— for example, you can specialize the solver to enforce static ordering ("always push asset A before asset B") or version ordering ("asset A must always run a version equal or greater than asset B").