# Draft or revise an essay

prompt used: "Visualize the essay's main points and use AI to enhance the visual presentation."

## description

Students could use an AI tool to help with revisions on an essay that they themselves have drafted. The AI can be prompted to focus on particular areas of struggle for the student--topic sentences, clarity of prose, organization, etc. The AI could also give the student ideas about topics to discuss in writing conferences with their instructor based on what its observing in the student's writing.

Depending on the course goals, this type of engagement with AI might give students too much content. You might want to set guidelines for appropriate or inappropriate use.

## activity

1. Log into chatGPT using the Harvard AI Sandbox

2. From search bar at the bottom of the page, specify that you'd like to use GPT 4 32K, since you'll input a significant amount of text (and GPT 3, 3.5, and 4 have word limits in the Harvard AI Sandbox).

3. First, type your questions and/or your prompt for the AI. Remember:

* If you only hit Enter or Return, this will automatically submit your prompt.

* You can also add three ticks (''') to indicate a paragraph break if you prefer.

5. For this activity, ask chatGPT to provide you with feedback on your writing:

* ask it to evaluate the clarity of your thesis

* ask it to evaluate your topic sentences

* ask it to evaluate the overall organization of your paper

4. Hit Shift + Enter, and then copy and paste the text you'd like chatGPT to give you feedback on. Remember to make clear what the text is, and then place it inside of quotation marks.

* For example, write:

* "Here is the paper:"

* "Here is the text:"

6. Once you have this feedback, you can ask chatGPT to provide you with specific areas to focus on during your upcoming writing conference with your instructor.

*

---

## TRANSCRIPT OF ACTIVITY EXAMPLE:

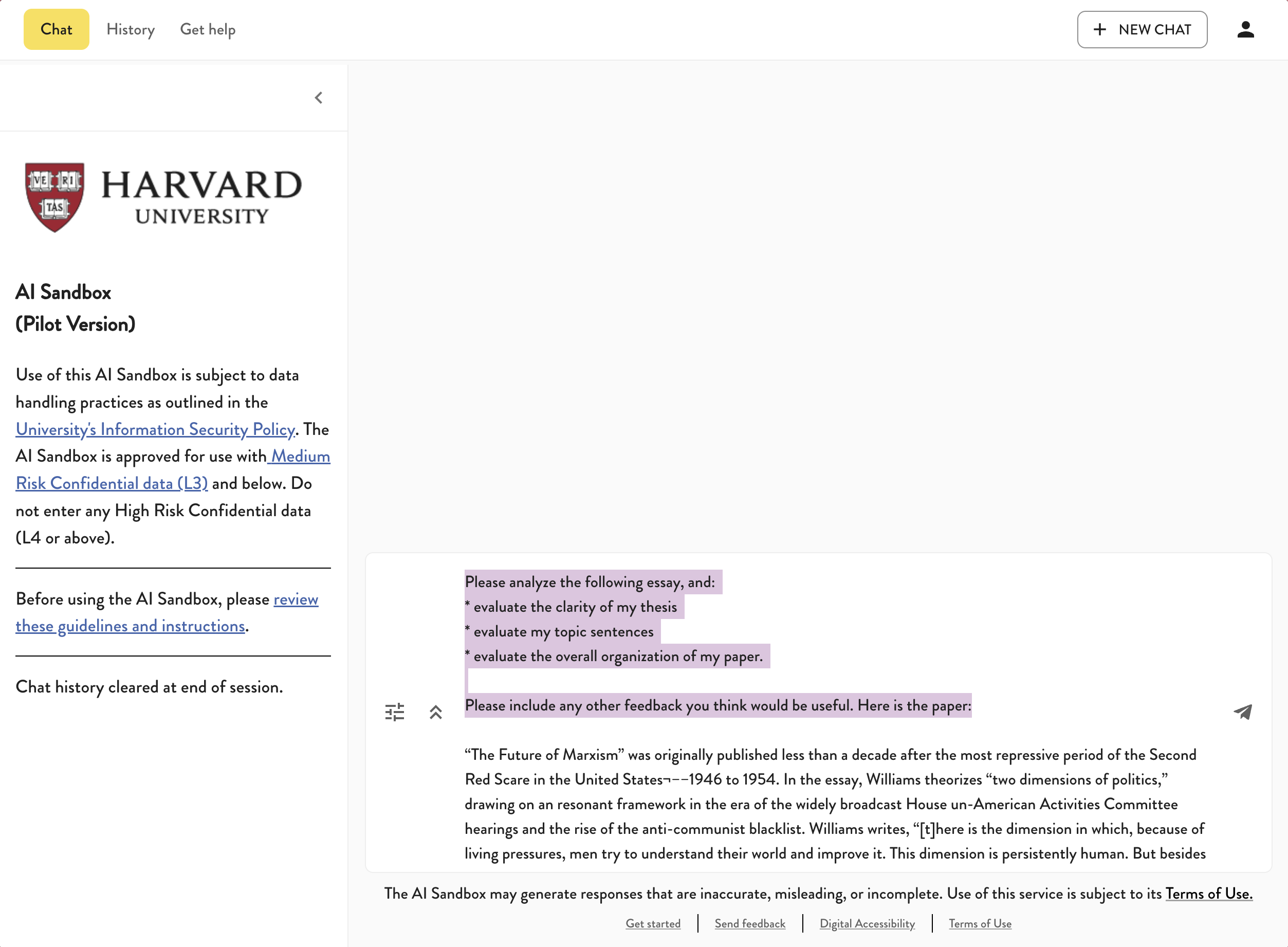

* USER:

* Please analyze the following essay, and:

* evaluate the clarity of my thesis

* evaluate my topic sentences

* evaluate the overall organization of my paper.

* Please include any other feedback you think would be useful. Here is the paper:

“The Future of Marxism” was originally published less than a decade after the most repressive period of the Second Red Scare in the United States¬––1946 to 1954. In the essay, Williams theorizes “two dimensions of politics,” drawing on an resonant framework in the era of the widely broadcast House un-American Activities Committee hearings and the rise of the anti-communist blacklist. Williams writes, “[t]here is the dimension in which, because of living pressures, men try to understand their world and improve it. This dimension is persistently human. But besides it, always, is that parading robot of polemic, which resembles human thinking in everything but its capacity for experience” (53). Williams ventriloquizes the HUAC examiner, posing his own version of the “$64 question,” so named by screenwriter and Hollywood Ten member Alvah Bessie during his 1947 HUAC hearing (Doherty 247). Yet instead of the standard “Are you now or have you ever been a member of the Communist Party?”, Williams’s imaginary questions come, first, from a left sectarian and, then, from a right-wing anti-communist. They suggest that “robotic” interpretations can emerge from the political Left and Right: “Are you a Marxist, a revisionist, a bourgeois reformist? Are you a Communist, a Left radical, a fellow traveler?” (Williams 53).

Uninterested in official stereotypes of communists as Kremlin-led, undifferentiated robots (Schrecker 131), Williams reconfigures political rhetoric used to repress the Left into a Left-sympathetic critique. In so doing, he posits the ongoing analytical power of ordinary language invoked throughout the 1940s and 50s to dehumanize communists, socialists, and fellow travelers. Williams’ use of the conceptual analogues of the Second Red Scare indicates this discourse’s dominance in midcentury Anglo-U.S.-American political thought. Like any articulation of dominant ideology, Williams does not express “only the isolable meanings and practices of the ruling class” (Williams, “B&S,” 39). He attempts to convey “alternative meanings and values, the alternative opinions and attitudes, even some alternative senses of the world, which can be accommodated and tolerated within a particular effective and dominant culture” (39).

In “The Future of Marxism,” Williams calls for a return to socialist principles, but to do so, he deploys what I will call, influenced by the work of Ellen Schrecker, the human-automaton convention. Constructing the popular image of communists, particularly in the U.S., the human-automaton convention was primarily deployed as a means of justifying communists’ repression. Notably, Williams’s studies of media provide a way into critiquing this convention, which is a central thematic feature of cultural works that constitute the U.S. Cold War imaginary. Williams’s columns for the BBC publication The Listener (which ran from 1968 to 1972) and his 1974 book, Television: Technology and Cultural Form, are foundational studies of the medium that furnish us with a theoretical means of assessing broadcast media as a primary site for the articulation and contestation of dominant ideology.

I will argue that the human-automaton convention retains representational influence by analyzing the convention’s contemporary application in the FX channel Reagan-era spy drama, The Americans. I ask if engaging this convention inevitably cedes ground to the countersubversive tradition––what Michael Rogin defines as the discursive “inflation, stigmatization, and dehumanization” of subversives (xiii). Whether in Williams’s use—which culminates in a call for “a recovery of something like [Marxism’s] whole tradition” (FOM, 65)—or expressed on contemporary US television, do the convention’s discursive ties to the historical forces of reaction prefigure a limited horizon of political possibility? What, given the 2018 publication of Williams’s essay in the New Left Review, is the conceptual and political utility of the human-robot convention today?

As Rogin has shown, U.S. media industries are a primary site for constructing the countersubversive tradition. While Rogin privileges the discursive power of the cinematic “screen” (“Preface,” xviii), I extend his emphasis to television as an increasingly significant, contemporary site where hegemonic political consciousness is reproduced. It’s critical to interrogate the contours and ideological substance of the countersubversive tradition because it upholds an exploitative order. As Williams has shown, the reproduction of this order depends, in part, on its superstructural persistence.

The Americans premiered in January 2013 and ran for six seasons, with the final episode airing in May 2018. Considered by many critics to be subversive, the show follows Soviet K.G.B. spies, aliases Elizabeth and Philip Jennings, who operate out of the Northern Virginia suburbs. Showrunner and former C.I.A. agent Joe Weisberg claims that The Americans “look[s] at the whole concept of ‘the enemy’…. at the worst of them—the K.G.B.—and humanize[s] them” (Toobin). Weisberg suggests that The Americans upsets the dominant perspective that communists are homogenous automatons, who lack an essential humanity or personhood. Developed in films like Ninotchka (1939), The Manchurian Candidate (1962), and Rocky IV (1985), communism’s ostensible destruction of complex subjectivity continues to shape mainstream cultural expectations. The Americans emerged to critical claim precisely along these lines. By centering communists’ affective experiences and complicated personal and professional lives, The Americans rejects the more overtly dehumanizing anti-communism of the midcentury in favor of what Williams describes, in a television column written for The Listener, as the “most necessary task…to see people in their own terms, in a complex of working and relating, rather than as the symbolic or abstract figures for which the dominant consciousness is already prepared” (Williams, “Pitmen and Pilgrims,” 78).

To counter the hegemonic representational logic of the U.S. Cold War imaginary, the show foregrounds interpersonal relationships and individual affect. The human-robot convention is important to this effort, as the example of protagonist Elizabeth Jennings shows. As Philip Drake argues, Elizabeth is a hardliner, fulfilling the “‘unsmiling Russian’” stereotype promoted by Ayn Rand during her analysis of the 1944 Hollywood film Song of Russia at her “friendly” HUAC testimony (Drake, 14). In her committed work through the high-risk Directorate S program, Elizabeth’s “robotic strength and endurance,” as one critic calls it, defines her from the series’ outset (Robinson). Much of Elizabeth’s spy-work implies a betrayal of the Marxist principles, when, for instance, she ruthlessly coerces a domestic laborer of color. Representing the official consciousness to which the show ostensibly responds, the C.I.A.’s Director of Operations and Planning for the Soviet Union says to Elizabeth in the first season, “You have no heart, no soul, no conscience.” Yet Elizabeth reflexively assents to the Centre until the show’s final season, the climax of which hinges on Elizabeth’s resistance to the K.G.B. (anti-Gorbachev) plan to develop a fully automated nuclear arsenal.

At times, Elizabeth is paralleled to machinery, as in season three/episode nine (“Do Mail Robots Dream of Electric Sheep?”), when Elizabeth and Philip break into a repair facility to bug the FBI’s mail robot. Discovering the facility’s bookkeeper working late in the offices, Philip continues to implant the listening device while Elizabeth talks with the elderly employee, who shares intimate details about her life. Parallel editing establishes that Philip’s work on the mail robot concurs with Elizabeth being “worked” by the bookkeeper, whose vulnerability moves Elizabeth to disclose her identity and personal past. As Philip completes his work on the mail robot, Elizabeth forces the bookkeeper to overdose on medication. The viewer sees that Elizabeth, like the mail robot, is hardwired to execute the mission.

Philip conveys the show’s vision of the human. Wary of the Soviet mission, Philip’s overriding desire for personal fulfillment figures him as the show’s titular “American,” culminating in his decision to join the self-actualization organization “est” (Erhard Seminars Training). Alongside Philip, the viewer learns est’s core tenets, sometimes visible in computer-generated-like script on a blackboard. A human meeting facilitator instructs attendees, “We’re all machines....Your lives are mechanically programmed—stimulus, response, stimulus, response.” Cuts to Philip making a drop periodically interrupt the meeting as the facilitator continues, “[B]ut if we’re nothing more than machines, programmed to respond to stimuli, what are we to make of the notion of Enlightenment? Enlightenment is knowing the truth, accepting that you are a machine.” Depicted seated at the meeting and executing the mission, the sequence’s clear articulation through Philip’s perspective allows the viewer to witness both his mechanical execution of a mission and to see his evolving self-consciousness of this work as automatic. Aware of himself as an automaton, Philip begins to distance himself from Directorate S, while Elizabeth continues to labor under a (robotic) false consciousness that nearly destroys her.

Still, Elizabeth comes to regret and resist her work for the Soviet Union. Ritualizing compunction, The Americans encourages the viewer to, in the words of Mark Fisher, “[l]ower[] [their] expectations” and adopt “[t]he attitude of ironic distance proper to postmodern capitalism…[which] is supposed to immunize us against the seductions of fanaticism” (Fisher 5). The show’s emphasis on regret provides the viewer’s primary access to communist characters’ “humanity,” reproducing the punitive logic of midcentury red-baiting, when leftists were forced in institutional settings like HUAC to publicly renounce and apologize for their commitments.

Williams gives us a way to see the human and robotic “dimensions of experience,” albeit in his own time and for the purposes of upholding a Left politics. A transferable framework for contemporary culture, the convention likewise risks conceding to a countersubversive imaginary. Leveraging these themes of Cold War memory, The Americans uses the human-robot convention to authorize only two dimensions of experience: the imperfect––but given the ability to name it as such––ethically superior life afforded by the U.S. capitalist state or a totalizing, robotic existence under Soviet communism. Underlining the show’s “end of history” narrative perspective, Elizabeth and Philip’s daughter, Paige, rebels in service of U.S. hegemony by ultimately electing to stay in the United States as her parents return to the (soon-to-collapse) Soviet Union. This allows The Americans to consign its “human” communists to the past, confirming William’s view that “dead radicals…can be seen as human beings; alive they are only instrumental and inconvenient” (“M&C”, 44).

* AI:

* Your essay is well-written and demonstrates a deep understanding of the topic at hand. Here are my evaluations based on the criteria you provided:

* **Clarity of Thesis**: Your thesis is not explicitly stated, which makes it difficult to identify. However, it seems to be centered around an analysis of the "human-automaton convention" in the context of Marxism, the Second Red Scare, and its representation in media, particularly in the TV show "The Americans." It would be beneficial to clearly state your thesis at the beginning of your essay to guide your readers.

* **Topic Sentences**: Your topic sentences are generally clear and provide a good overview of the paragraph's content. However, some paragraphs are quite long and cover multiple topics, which can make it difficult for the reader to follow your argument. Consider breaking these up into smaller paragraphs each with a clear topic sentence.

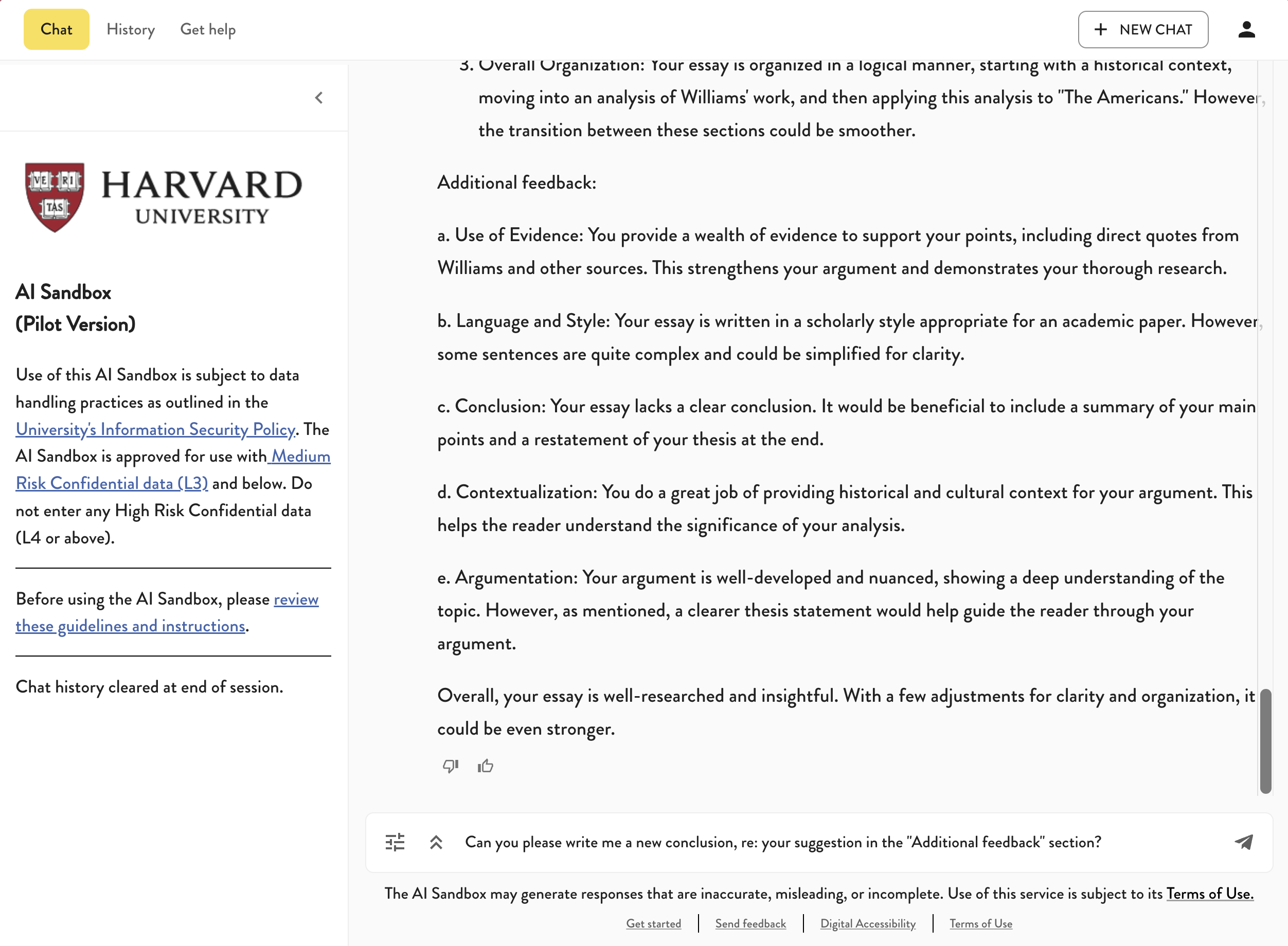

* **Overall Organization**: Your essay is organized in a logical manner, starting with a historical context, moving into an analysis of Williams' work, and then applying this analysis to "The Americans." However, the transition between these sections could be smoother.

* Additional feedback:

* a. Use of Evidence: You provide a wealth of evidence to support your points, including direct quotes from Williams and other sources. This strengthens your argument and demonstrates your thorough research.

* b. Language and Style: Your essay is written in a scholarly style appropriate for an academic paper. However, some sentences are quite complex and could be simplified for clarity.

* c. Conclusion: Your essay lacks a clear conclusion. It would be beneficial to include a summary of your main points and a restatement of your thesis at the end.

* d. Contextualization: You do a great job of providing historical and cultural context for your argument. This helps the reader understand the significance of your analysis.

* e. Argumentation: Your argument is well-developed and nuanced, showing a deep understanding of the topic. However, as mentioned, a clearer thesis statement would help guide the reader through your argument.

* Overall, your essay is well-researched and insightful. With a few adjustments for clarity and organization, it could be even stronger.

* USER:

* Can you please write me a new conclusion, re: your suggestion in the "Additional feedback" section?

* AI:

* Certainly, here's a suggested conclusion for your essay: "In conclusion, this essay has examined the "human-automaton convention" in the context of Marxism, the Second Red Scare, and its representation in media, particularly in the TV show "The Americans." Through a detailed analysis of Williams' work and its application to "The Americans," we have seen how this convention has been used to dehumanize communists and justify their repression, while also being employed as a critique of the dominant ideology. However, the use of this convention also risks conceding to a countersubversive imaginary, as evidenced in the portrayal of communists in "The Americans." The show's emphasis on regret and its "end of history" narrative perspective ultimately uphold the punitive logic of midcentury red-baiting and reinforce the dominance of the U.S. capitalist state. It is clear that while the human-automaton convention can provide a powerful tool for critique, it also carries the risk of reinforcing the very ideologies it seeks to challenge. This analysis underscores the need for a nuanced understanding of the use of such conventions in media and their implications for our understanding of history and politics."