Decorator

# Design pattern - decorator

URL: https://refactoring.guru/design-patterns/decorator

## **Real-World Analogy**

> **Decorator** is a structural design pattern that lets you attach new behaviors to objects by placing these objects inside special wrapper objects that contain the behaviors.

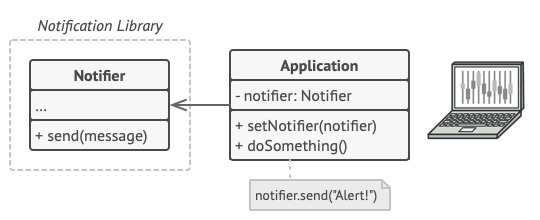

## **Problem**

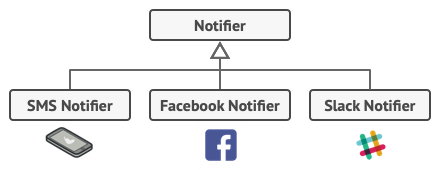

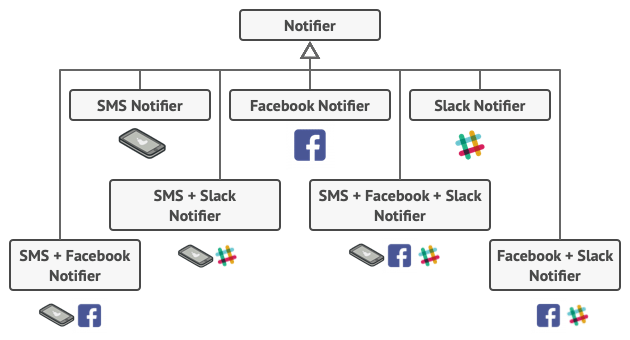

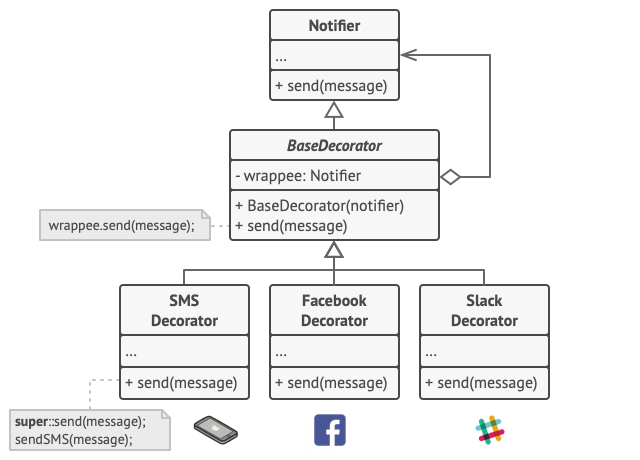

- Others would like to be notified on **Facebook** or **Slack** notifications.

- You extended the `Notifier` class and put the additional notification methods into new subclasses.

- This approach would bloat the code immensely.

## **Solution**

Extending a class.

- Inheritance is static. You can’t alter the behavior of an existing object at runtime. You can only replace the whole object with another one that’s created from a different subclass.

- Subclasses can have just one parent class. In most languages, inheritance doesn’t let a class inherit behaviors of multiple classes at the same time.

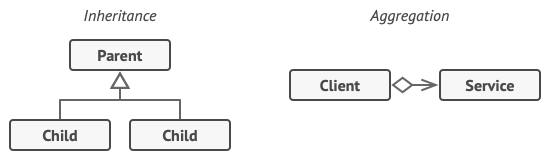

- Using *Aggregation* or *Composition* instead of *Inheritance*.

Aggregation/composition is the key principle behind many design patterns, including Decorator.

*Inheritance vs. Aggregation*

## **Decorator**

- “Wrapper” is the alternative nickname for the Decorator pattern that clearly expresses the main idea of the pattern.

- A *wrapper* is an object that can be linked with some *target* object.

- The wrapper contains the same set of methods as the target and delegates to it all requests it receives.

- The wrapper may alter the result by doing something either before or after it passes the request to the target.

In our notifications example, let’s leave the simple email notification behavior inside the base `Notifier` class, but turn all other notification methods into decorators.

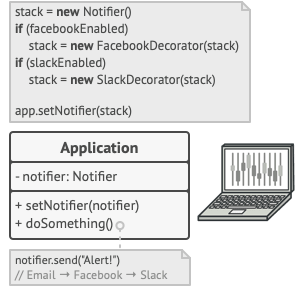

- The client code would need to wrap a basic notifier object into a set of decorators that match the client’s preferences.

- All decorators implement the same interface as the base notifier.

## **Another Example**

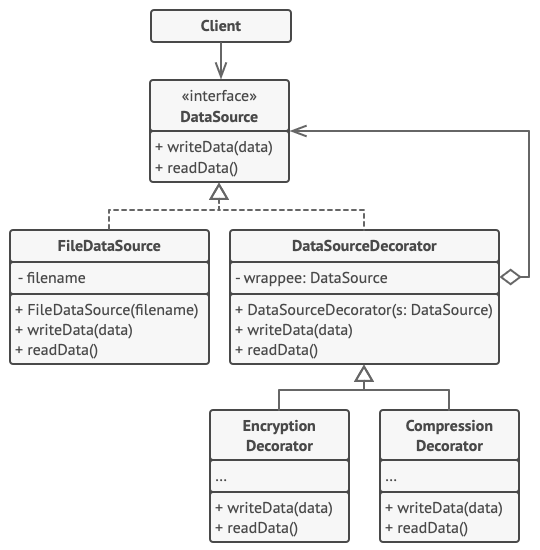

In this example, the **Decorator** pattern lets you compress and encrypt sensitive data independently from the code that actually uses this data.

## **Applicability**

- **Use the Decorator pattern when you need to be able to assign extra behaviors to objects at runtime without breaking the code that uses these objects.**

The Decorator lets you structure your business logic into layers, create a decorator for each layer and compose objects with various combinations of this logic at runtime. The client code can treat all these objects in the same way, since they all follow a common interface.

- **Use the pattern when it’s not possible to extend an object’s behavior using inheritance.**

Many programming languages have the `final` keyword that can be used to prevent further extension of a class. Not in Ruby.

****How to Implement****

1. Make sure your business domain can be represented as a primary component with multiple optional layers over it.

2. Figure out what methods are common to both the primary component and the optional layers. Create a component interface and declare those methods there.

3. Create a concrete component class and define the base behavior in it.

4. Create a base decorator class. It should have a field for storing a reference to a wrapped object. The field should be declared with the component interface type to allow linking to concrete components as well as decorators. The base decorator must delegate all work to the wrapped object.

5. Make sure all classes implement the component interface.

6. Create concrete decorators by extending them from the base decorator. A concrete decorator must execute its behavior before or after the call to the parent method (which always delegates to the wrapped object).

7. The client code must be responsible for creating decorators and composing them in the way the client needs.

## **Pros and Cons**

- You can extend an object’s behavior without making a new subclass.

- You can add or remove responsibilities from an object at runtime.

- You can combine several behaviors by wrapping an object into multiple decorators.

- *Single Responsibility Principle*. You can divide a monolithic class that implements many possible variants of behavior into several smaller classes.

- It’s hard to remove a specific wrapper from the wrappers stack.

- It’s hard to implement a decorator in such a way that its behavior doesn’t depend on the order in the decorators stack.

- The initial configuration code of layers might look pretty ugly.

## **Relations with Other Patterns**

- **[Adapter](https://refactoring.guru/design-patterns/adapter)** changes the interface of an existing object, while **[Decorator](https://refactoring.guru/design-patterns/decorator)** enhances an object without changing its interface. In addition, *Decorator* supports recursive composition, which isn’t possible when you use *Adapter*.

- **[Adapter](https://refactoring.guru/design-patterns/adapter)** provides a different interface to the wrapped object, **[Proxy](https://refactoring.guru/design-patterns/proxy)** provides it with the same interface, and **[Decorator](https://refactoring.guru/design-patterns/decorator)** provides it with an enhanced interface.

- **[Chain of Responsibility](https://refactoring.guru/design-patterns/chain-of-responsibility)** and **[Decorator](https://refactoring.guru/design-patterns/decorator)** have very similar class structures. Both patterns rely on recursive composition to pass the execution through a series of objects. However, there are several crucial differences.

The *CoR* handlers can execute arbitrary operations independently of each other. They can also stop passing the request further at any point. On the other hand, various *Decorators* can extend the object’s behavior while keeping it consistent with the base interface. In addition, decorators aren’t allowed to break the flow of the request.

- **[Composite](https://refactoring.guru/design-patterns/composite)** and **[Decorator](https://refactoring.guru/design-patterns/decorator)** have similar structure diagrams since both rely on recursive composition to organize an open-ended number of objects.

A *Decorator* is like a *Composite* but only has one child component. There’s another significant difference: *Decorator* adds additional responsibilities to the wrapped object, while *Composite* just “sums up” its children’s results.

However, the patterns can also cooperate: you can use *Decorator* to extend the behavior of a specific object in the *Composite* tree.

- Designs that make heavy use of **[Composite](https://refactoring.guru/design-patterns/composite)** and **[Decorator](https://refactoring.guru/design-patterns/decorator)** can often benefit from using **[Prototype](https://refactoring.guru/design-patterns/prototype)**. Applying the pattern lets you clone complex structures instead of re-constructing them from scratch.

- **[Decorator](https://refactoring.guru/design-patterns/decorator)** lets you change the skin of an object, while **[Strategy](https://refactoring.guru/design-patterns/strategy)** lets you change the guts.

- **[Decorator](https://refactoring.guru/design-patterns/decorator)** and **[Proxy](https://refactoring.guru/design-patterns/proxy)** have similar structures, but very different intents. Both patterns are built on the composition principle, where one object is supposed to delegate some of the work to another. The difference is that a *Proxy* usually manages the life cycle of its service object on its own, whereas the composition of *Decorators* is always controlled by the client.

example:

```ruby

# The base Component interface defines operations that can be altered by

# decorators.

class Component

# @return [String]

def operation

raise NotImplementedError, "#{self.class} has not implemented method '#{__method__}'"

end

end

# Concrete Components provide default implementations of the operations. There

# might be several variations of these classes.

class ConcreteComponent < Component

# @return [String]

def operation

'ConcreteComponent'

end

end

# The base Decorator class follows the same interface as the other components.

# The primary purpose of this class is to define the wrapping interface for all

# concrete decorators. The default implementation of the wrapping code might

# include a field for storing a wrapped component and the means to initialize

# it.

class Decorator < Component

attr_accessor :component

# @param [Component] component

def initialize(component)

@component = component

end

# The Decorator delegates all work to the wrapped component.

def operation

@component.operation

end

end

# Concrete Decorators call the wrapped object and alter its result in some way.

class ConcreteDecoratorA < Decorator

# Decorators may call parent implementation of the operation, instead of

# calling the wrapped object directly. This approach simplifies extension of

# decorator classes.

def operation

"ConcreteDecoratorA(#{@component.operation})"

end

end

# Decorators can execute their behavior either before or after the call to a

# wrapped object.

class ConcreteDecoratorB < Decorator

# @return [String]

def operation

"ConcreteDecoratorB(#{@component.operation})"

end

end

# The client code works with all objects using the Component interface. This way

# it can stay independent of the concrete classes of components it works with.

def client_code(component)

# ...

print "RESULT: #{component.operation}"

# ...

end

# This way the client code can support both simple components...

simple = ConcreteComponent.new

puts 'Client: I\'ve got a simple component:'

client_code(simple)

puts "\n\n"

# ...as well as decorated ones.

#

# Note how decorators can wrap not only simple components but the other

# decorators as well.

decorator1 = ConcreteDecoratorA.new(simple)

decorator2 = ConcreteDecoratorB.new(decorator1)

puts 'Client: Now I\'ve got a decorated component:'

client_code(decorator2)

```

## Draper

URL: https://github.com/drapergem/draper