---

title: "#22.5 TBD 讀網站會 - Continuous Integration (CI)"

tags: Meetups

date: 2022-06-30

---

> individuals practice Trunk-Based Development, and teams practice CI

> -- *Agile* Steve Smith

## Continuous Integration - as defined

For many years CI has been accepted by a portion of software development community to mean a daemon process that is watching the source-control repository for changes and verifying that they are correct, **regardless of branching model**.

However, the original intention was to focus on the verification **single integration point** for the developer team. And do it daily if not more. The idea was for developers themselves to develop habits to ensure everything going to that shared place many times a day was of high enough quality, and for the CI server to merely verify that quality, nightly.

因此, 最初的目的是專住在開發團隊的單一整合點的驗證, 並且至少每天都做一次這樣的驗證. 這樣的作法是讓開發人員自己養成習慣, 確保每天訪問多次Git server的所有內容都具備很高的質量, 且CI server會在每晚驗證上面內容的質量.

CI as we know it today was championed by Kent Beck, as one of the practices he included in “[Extreme Programming](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Extreme_programming)" in the mid-nineties. Certainly in 1996, on the famous ‘Chrysler Comprehensive Compensation System’ [(C3) project](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chrysler_Comprehensive_Compensation_System) that Kent had all developers experiencing and enjoying the methodology - including the continuous integration aspect. The language for that project was Smalltalk and the single integration point was a Smalltalk image (a technology more advanced than a “mere” source-control systems that rule today).

Thus, the intention of CI, as defined, was pretty much exactly the same as Trunk-Based Development, that emerged elsewhere. Trunk-Based Development did not say anything about Continuous Integration daemons directly or indirectly, but there is an overlap today - the safety net around a mere branching model (and a bunch of techniques) is greatly valued.

Martin Fowler (with Matt Foemmel) called out [Continuous Integration in an article in 2000](https://www.martinfowler.com/articles/originalContinuousIntegration.html), (rewritten in [2006](https://www.martinfowler.com/articles/continuousIntegration.html)), and ThoughtWorks colleagues went on to build the then-dominant “Cruise Control" in early 2001. [Cruise Control](http://cruisecontrol.sourceforge.net/) co-located the CI configuration on the branch being built next to the build script, as it should be.

## Integration: Human actions

It is important to note that the build script which developers run prior to checking in, is the same one which is followed by the CI service (see below). The build is broken into gated steps due to a need for succinct communication to you the developer as well as teammates. The classic steps would be: compile, test-compile, unit test invocation, service test invocation, functional test invocation. Those last two are part of the integration tests class.

將Build拆解成幾個閥控步驟, 需要上一步有過才會有下一步, 便於開發人員與團隊成員會進行簡明的溝通.

Compile -> test-compile -> unit test -> service test -> functional test

最後兩步驟都會被分類在整合測試的項目內

If the build passed on the developer’s workstation, and the code is up to date with HEAD of what the team sees for trunk, then the developer checks in the work (commit and push for Git). Where that goes to depends on which way of working the team is following. Some smaller teams will push straight to trunk, and may do so multiple times a day (see Committing straight to the trunk). Larger teams may push to a patch-review system, or use short-lived feature branches, even though this can be an impediment to throughput.

大小團隊採用TBD該有的習慣與作法.

## CI services: Bots verifying human actions

Every development team bigger than three people needs a CI daemon to guard the codebase against bad commits and timing mistakes. Teams have engineered build scripts which execute quickly. This should apply from compilation through functional testing (perhaps leveraging mocking at several levels) and packaging.

However, there is no guarantee that a developer would run the build script before committing.

The CI daemon fulfills that role by verifying commits to be good once they land in the trunk.

Enterprises have either built a larger scaled capability around their CI technology, so that it can keep up with the commits/pushes of the whole team or they use batching of commits which takes up less computing power to track and verify work.

團隊人數超過3人時, 都應該要有一個CI server來保護codebase.

團隊會設計一些build scripts, 這腳本應該要有compile到functional testing的功能.

但儘管如此, 還是很難避免開發人員先commit了但沒執行該腳本.

但CI可以透過該腳本來驗證該commit, 在該commit要被整並到trunk之前.

企業會為繞在CI技術上構建可以伸縮處理的能力, 以便CI可以跟上整個團隊的提交迭代速度.

### Radiators

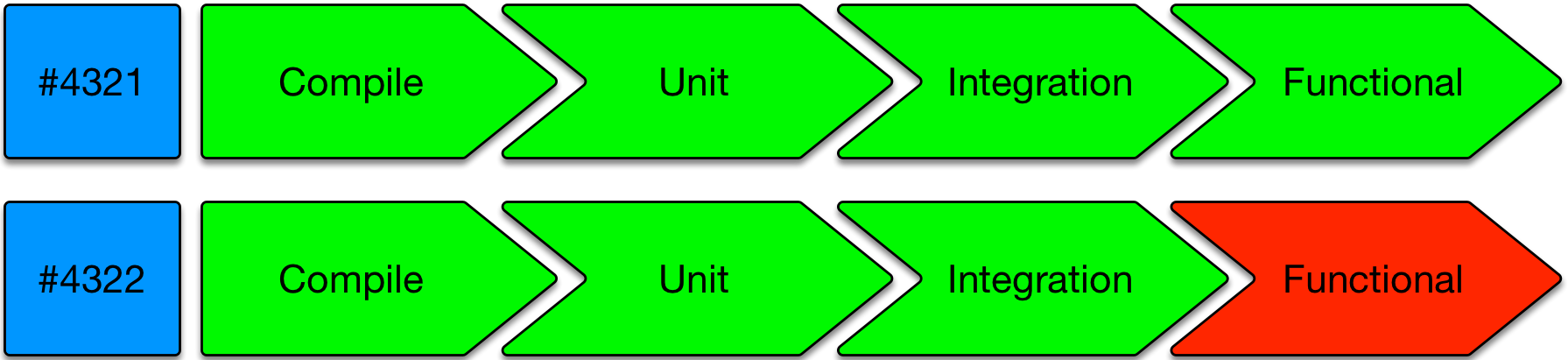

A popular radiator-style visual indication of progress would be those shown as a left-to-right series of Green (passing) or Red (failing) icons/buttons with a suitably short legend:

This should go up on TVs if developers are co-located. It should also be a click through from notification emails.

### Quick build news

The elapsed time between the commit and the “this commit broke the build” notification, is key. That is because the cost to repair things in the case of a build breakage goes up when additional commits have been pushed to the branch. One of the facets of the ‘distance’ that we want to reduce (refer five-minute overview) is the *distance* to break.

commit提交後到因為該commit提交後而壞掉的通知, 這裡經過的時間長度是關鍵.

因為有可能後面有額外的commit被推送進到分支上了.

這樣的話, hotfix成本就便高了.

所以想要減少"距離"的一個面向的話, 這是一個要打破的距離.

### Pipelines - further reading

Note: Continuous Integration Pipelines are better described in the bestselling Continuous Delivery book. So are dozens of nuanced, lean inspired concepts for teams pushing that far.

## Advanced CI topics

### CI service builds per commit or batching?

Committing/pushing directly to the shared trunk may be fine for teams with only a few commits a day. Fine too for teams that only have a few developers who trust each other to be rigorous on their workstation before committing (as it was for everyone in the 90’s).

Setups having the CI server single threading on builds and the notification cycle around pass/fail will occasion lead to the batching in a CI job. This is not a big problem for small teams. Batching is where one build is verifying two or more commits in one go. It is not going to be hard to pick apart a batch of two or three to know which one caused the failure. You can believe that with confidence because of the high probability the two commits were in different sections of the code base and are almost never entangled.

If teams are bigger, though, with more commits a day then pushing something incorrect/broken to trunk could be disruptive to the team. Having the CI daemon deal with **every commit** separately is desirable. If the CI daemon is single-threading “jobs” there is a risk that the thing could fall behind.

#### *Master / Slave CI infrastructure*

More advanced CI Server configurations have a master and many slaves setup so that build jobs can be *parallelized*. That’s more of an investment than the basic setup, and but is getting easier and easier in the modern era with evolved CI technologies and services.

The likes of Docker means that teams can have build environments that are perfectly small representations of prod infra for the purposes of testing.

平行化 CI 的建構流程,已經是基本設施。可以用類似 Docker 的工具達成測試的目的。

#### *Tests are never green incorrectly.*

Well written tests, that is - there are fables of suites of 100% passing unit tests with no assertions in the early 2000’s.

Some teams focus 99.9% of their QA automation on functional correctness. You might note that for a parallelized CI-driven ephemeral testing infrastructure, that response times for pages are around 500ms, where the target for production is actually 100ms. Your functional tests are not going to catch that and fail - they’re going to pass. If you had non-functional tests too (that 0.1% case) then you might catch that as a problem. Maybe it is best to move such non-functional automated tests to a later pipeline phase, and be pleased that so many functional tests can run through so quickly and cheaply and often, on elastic (albeit ephemeral) CI infrastructure.

Here is a claim: Tests are never green (passing) incorrectly. The inverse - a test failing when the prod code it is verifying actually good - is common. QA automators are eternally fixing (somehow) smaller numbers of flakey tests.

A CI build that is red/failing often, or an overnight CI job that tests everything that happened in the day - and is always a percentage failing is of greatly reduced value.

A regular CI build that by some definition is comprehensive, well written and always green unless there’s a genuine issue is extremely valuable.

Once you get to that trusted always green state, it is natural to run it as often as you can.

### CI Pre or Post Commit?

In terms of breakages, whether incorrect (say ‘badly formatted’), or genuinely broken, finding that out after the commit is undesirable. Fixing things while the rest of the team watches or waits is a team-throughput lowering practice.

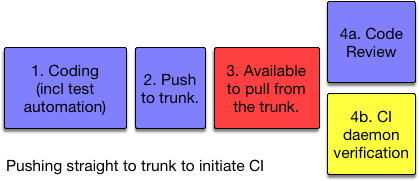

Yellow = automated steps, Red = a potential to break build for everyone

Note: for committing/pushing straight to the shared trunk, code review and CI verification can happen in parallel. Most likely though is reviews happening after the CI daemon has cast its vote on the quality of the commit(s).

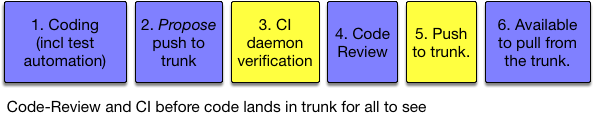

Better setups have code-review and CI verification before the commit lands in the trunk for all to see:

It is best to have a human agreement (the code review), and machine agreement (CI verification) before the commit lands in the trunk. There is still room for error based on timing, so CI needs to happen a second time after the push to the shared trunk, but the chance of the second build failing so small that an automated revert/roll-back is probably the best way to handle it (and a notification).