# GMT3A: A brief reintroduction to writing music in 12 ED2 <12 19 28 34 ...]

(alternate title: How to write "normal" contemporary western music in the "normal" tuning system that most humans and software protocols on Earth currently use in the 21st century)

> **12 ED2**

> 12 multiplicatively equal divisions of the interval $2/1$ that is homomorphic to $\mathbb{Z}/12\mathbb{Z}$ up to octave equivalence.

>

> Val mapping of prime intervals:

> Octave: 12 edosteps

> Tritave: 19 edosteps

> Pentave: 28 edosteps

> Septave: 34 edosteps

> $\vdots$

> Other installments:

> \> **<u>Section. I Parts 1-4</u>**

> [Section. I Parts 5-](https://hackmd.io/@euwbah/GMT3B)

###### tags: `GMT`

###### reading time: 2-10 hours

## Prerequisites:

Aural and theoretical knowledge of intervals & you really like music.

## Disclaimer:

I don't claim to know any music history, and all but the most 'efficiently useful' of sources are left out for the sake of brevity.

## Abstract

A informal guide for those wanting to partake in the insurmountable task of creating 'tonal' music (whatever that means) in the context of the 21st century.

Briefly going through all the axioms and ideas built up in prior installations of GMT, we focus on the connecting of ideas, and try to answer:

- [ ] **The universal human ability to cognize and rationalize sounds.**

- [ ] **What is 'tonal'**

- [ ] **Why parallel fifths are 'bad'**

- [ ] What 'chords', 'progressions', 'keys' really are

- [ ] The pursuit of tonic clarity

- [ ] The unique properties of having 12 multiplicatively equal intervals that sum up to an octave.

- [ ] The naming convention of notes

- [ ] How to use consonance and dissonance

- [ ] What 'scales' really are.

- [ ] Zooming in on functional melody (on the harmonic implications of melody instead of themating development/phrasing)

- [ ] How to 'voice' chords

This guide reintroduces basic music theory in a (hopefully) simple and trivial manner, without relying on the recursively defined 'rocket science' concepts. (E.g. What is a major scale? Ionian. What is Ionian? The major scale. _Why_ is a major scale?)

In the style of [Bernstein's introduction to music](https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Gt2zubHcER4&ab_channel=paxwallacejazz), we work chronologically to give an overview on how the evolution process of music has allowed music to be what it is today. The point is to construct an understanding of music from [first principles](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/First_principle).

That also means, a significant chunk of this guide will initially appear to be overanalyzing and overthinking a lot of things that you may find trivial. But trust the process, and these very 'trivial' facts is later used to easily construct, explain and create applications for modern tonal harmony, 'bebop' improvisation, and whatever other things you want to do with the standard tuning system of today.

This will give you an introductory insight on how ancient musicians had to make sense of music without having 'standard theory' or the internet. The thinking process we use directly transfers to any tuning system you'd like. So think of it as a one-time investment to take your first step in the most general, general music theory there is.

A lot of important proofs and details will be left out so that this reads more like a '12 EDO for dummies guide' and less like a dissertation, but you should be able to find more rigorous explanations in the other installations of GMT.

> _We decided that ['trivial'](http://www.theproofistrivial.com/) means 'proved'. So we joked with the mathematicians: We have a new theorem --- that mathematicians can prove only trivial theorems, because every theorem that's proved is trivial._

>

> Richard P. Feynman, 1997

[TOC]

# Section I: Axioms of sound

This section recapitulates and summarizes the applicable axioms of sound that we will use to construct our 12ED2 music theory in the next section.

For a more thorough introduction, read [GMT1: Overanalyzing the perfect cadence](/EOngehUxRjiIgewlNM7fUg)

:::info

#### NOTE

The linked pages, videos and other resources saves me lots of writing so it's recommended to check out all the resources in this article. Especially this next one.

:::

## I1. [In the beninging](https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vacJSHN4ZmY&ab_channel=TikendrajitRabha)

...there was a human need to express nature, order, stucture, divinity, life, and spontaneity through the medium of sound.

During pre-literate/prehistoric times, it is hypothesized that [there was singing](https://academic.oup.com/book/26285), the use of natural [lithophones](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lithophone), and bone flutes and natural reed instruments (that biodegrade, so there is no real evidence of this). Blah blah blah...

The main takeaway for this era was the nature of which music was conceived. There was no real functional need for 'music'. Even 'caveman art' could have functional, instructional and documentative uses, but music is merely a natural spontaneous expression intended to [satiate the need](https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1364661313000491) for dopamine, opioids, cortisol, CRH, ACRH, serotonin, oxytocin, etc...

At this point in time, a good 'song' serves the sole purpose of 'feeling good', or maybe just 'feeling' anything. Prehistoric functional harmony = pure neurochemistry.

Fast forward to the age of writing stuff down (antiquity): music was monophonic, mainly focused on text that was religious or otherwise, and melody was improvised and passed down aurally. Any written down 'notes' (e.g. cantillation marks in the [Torah](https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4EbEUZGGgOU&ab_channel=myjewishlearning), [Quran](https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=i9_4Js7hBcI&ab_channel=essentialilm), [Vedic/Shloka Chanting](https://grdiyers.weebly.com/chanting-rules.html) amongst many others) were gestural and a means of recalling the gist of what to sing, but there were no concrete names for the notes they were using. Note that the earliest discovered music notation with concretely defined notes was in the 6th/7th century:

<iframe width="560" height="315" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/0ZhMeRUNpIU" title="YouTube video player" frameborder="0" allow="accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture" allowfullscreen></iframe>

To dig further into how this notation system was defined I would highly recommend this series:

<iframe width="560" height="315" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/htxai61UZTM" title="YouTube video player" frameborder="0" allow="accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture" allowfullscreen></iframe>

Here, music serves an added purpose. On top of pure brain tingling sensations, music now does story telling, worship, painting a mental imagery, expressing an awe of nature and divinity, or evoking some specific emotion. Fast forward a bit, we get evidence of more secular and folk songs. [Ai vist lo lop?](https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ywj0K-oRc5A&ab_channel=KiwiVdS) Nice story. Down to capitalism. Boo the government = 100 monthly plays in 1500CE. Very functional.

However, there's something that was created in 600BC ish in Sumer then later independently reinvented by Pythagoras of Samosa triangles and Samos, that would contribute greatly to how european classical music was developed: the [monochord](https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gYtSI4-ShLU&ab_channel=UlrichSch%C3%BCtz).

-----

## I2. Mono/Bi/Tri/n-chord: The birth of modern tonality

Here is a monochord being played to demonstrate the tuning of Hindustani/Carnatic classical music:

<iframe width="560" height="315" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/PQjWyBvLfqM" title="YouTube video player" frameborder="0" allow="accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture" allowfullscreen></iframe>

For more info on the tuning system in the above video (semi-related topic), you can check out [The science of music | Vidyadhar Oke | TEDxIITGandhinagar](https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ipYLnhC5YDo&ab_channel=TEDxTalks)

Explanation & brief history of the monochord:

<iframe width="560" height="315" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/3vXfU5_7_KA" title="YouTube video player" frameborder="0" allow="accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture" allowfullscreen></iframe>

The monochord was a scientific, musical, and astrological (and perhaps, even philosophical) device which allowed Pythogoras and friends to figure out something very important about frequencies, resonances, sound and music.

It's an instrument with one string (the previous video was technically a _bichord_), where you could play it by simply plucking the string. Or, you could put a bridge somewhere along the monochord to reduce the length of the resonating part of the string to increase its pitch. Or, instead of a bridge, you could also lightly touch a specific point on it with your other hand, and if you manage to divide the string length by a 'simple-enough' ratio like 1/5th or 1/3rd, you will get higher pitched notes which are familiarly known to string players as 'harmonics'.

Then, you could put multiple strings so that you can pluck them at the same time to hear how different pitches interact.

There's in fact an [online monochord simulator](https://chromatone.center/practice/sound/monochord/), but for the sake of having embeddable examples, I'll use xenpaper.com, which is a really good tool for playing with frequencies and intervals.

Now, Pythagoras and friends noted a few important things:

### 1. The frequency of the note was inversely related to the length of the string: halve length = double the frequency

<iframe width="560" height="200" src="https://xenpaper.com/#embed:(1)(env%3A3999)%0A1%2F1_2%2F1_3%2F2_4%2F4_5%2F4_6%2F4_7%2F4_8%2F8_9%2F8_10%2F8_11%2F8_12%2F8_13%2F8_14%2F8_15%2F8_16%2F8%0A" title="Xenpaper" frameborder="0"></iframe>

Each fraction represents a frequency ratio with respect to an arbitrary fundamental $1/1$ pitch.

- $1/1$ is 1 times the frequency of the fundamental frequency, 1 times the string length.

- $2/1$ is 2 times the fundamental frequency, $1/2$ string length

- $3/2$ is 1.5 times frequency, $2/3$ string length.

- $\text{new freq} = \frac{\text{old string len}}{\text{new string len}}\times \text{old freq}$

Note that the fundamental pitch is arbitrary (unless you have perfect pitch). For example, here is the above example but with a higher fundamental pitch.

<iframe width="560" height="200" src="https://xenpaper.com/#embed:(1)(env%3A3999)%7Br330hz%7D%0A1%2F1_2%2F1_3%2F2_4%2F4_5%2F4_6%2F4_7%2F4_8%2F8_9%2F8_10%2F8_11%2F8_12%2F8_13%2F8_14%2F8_15%2F8_16%2F8%0A" title="Xenpaper" frameborder="0"></iframe>

It should feel like the exact same 'shape' as the first example but in a 'higher key'. This type of 'same shape, different fundamental' phenomenon is contemporarily known as [_constant structure_](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Constant_structure). However, it is clear that constant structure a trivial biproduct of how frequencies and notes work.

### 2. To 'add' musical intervals, you multiply the ratios

Lets say $5/4$ is a major third, and $6/5$ is a minor third. We know from 'normal' music theory that a major third plus a minor third = a perfect fifth.

$$

\begin{align*}

\therefore \text{P5} &= 5/4 \cdot 6/5\\

&= 3/2

\end{align*}

$$

<iframe width="560" height="250" src="https://xenpaper.com/#embed:(1%2F2)(env%3A3096)%7Br330hz%7D%0A1%2F1_%5B1%2F1_5%2F4%5D._%23M3%0A%7Br5%2F4%7D_1%2F1_%5B1%2F1_6%2F5%5D._%23m3_relative_to_M3%0A%7Br330hz%7D_1%2F1_%5B1%2F1_5%2F4%5D_%5B1%2F1_5%2F4_3%2F2%5D.%0A1%2F1_3%2F2_%5B1%2F1_3%2F2%5D_%23M3_%2B_m3_%3D_P5%0A" title="Xenpaper" frameborder="0"></iframe>

Similarly, to 'subtract' intervals, divide. Lets say it is given that $2/1$ is an octave, and $4/3$ is a perfect fourth, then

$$

\begin{align*}

\text{P5} &= \text{P8} - \text{P4}\\

&\cong 2/1 \div 4/3\\

&= \frac{2}{1} \cdot \frac{3}{4}\\

&= 3/2

\end{align*}

$$

<iframe width="560" height="250" src="https://xenpaper.com/#embed:(1%2F2)(env%3A3096)%7Br220hz%7D%0A1%2F1_%5B1%2F1_2%2F1%5D._%23P8%0A1%2F1_%5B1%2F1_4%2F3%5D._%23P4%0A1%2F1_%5B1%2F1_2%2F1%5D_%5B1%2F1_2%2F1_4%2F3%5D._%231%2C4%2C8%0A%7Br4%2F3%7D_1%2F1_3%2F2_%5B1%2F1_3%2F2%5D_%23P8_-_P4_%3D_P5%0A" title="Xenpaper" frameborder="0"></iframe>

### 3. Prime numbers/factorization makes it easy to figure out new intervals.

Now that we know intervals can add/subtract to form other intervals by means of multiplying/dividing the frequency (or do the inverse operation on the string length), then we can apply the knowledge of the [_fundamental theorem of arithmetic_](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fundamental_theorem_of_arithmetic):

> Any number can be represented as a product of primes, and each number only has one unique representation.

For example, 6 decomposes into primes $3\cdot 2$, and no matter what you do, there are no other ways to multiply any number of primes and get the number 6. One $3$ multiplied by one $2$ can only equal 6 and nothing else.

Since we are multiplying intervals to 'add' them, this means intervals actually obey the fundamental theorem of arithmetic. We only need to know what the 'prime' intervals are, i.e. $\{2, 3, 5, 7, 11, 13, \ldots \}$, and from those intervals, we can construct any other interval we need as a product of those prime intervals.

For example, lets look at the interval $45/32$, and assume we don't know what interval it is (if you do, you probably should skip to the second half of this article).

We know that $45$ decomposes to $3\cdot 3\cdot 5$, and $32$ decomposes to $2\cdot2\cdot2\cdot2\cdot2$. In other words, $45/32 = (3^2\cdot 5)/(2^5) = 2^{-5}\cdot 3^2 \cdot 5^1$.

Then, we only need to know what $2$, $3$ and $5$ stands for:

<iframe width="560" height="200" src="https://xenpaper.com/#embed:(1%2F2)(env%3A3096)%7Br220hz%7D%0A%5B1%2F1_2%2F1%5D-._%23_2_is_an_octave%0A%5B1%2F1_3%2F1%5D-._%23_3_is_a_fifth_%2B_octave%0A%5B1%2F1_5%2F1%5D-._%23_5_is_a_major_third_%2B_2_octaves" title="Xenpaper" frameborder="0"></iframe>

Thus, we can deduce that:

$$

\begin{align*}

45/32 &= 2^{-5}\cdot 3^2 \cdot 5^1\\

&\cong -5 \text{ octave } + 2 (\text{fifth}+\text{octave}) + 1 (\text {maj 3rd} + 2\text{ octave})\\

&= -5 \text{ octave } + 2\text{ fifth}+ 2\text{ octave} + 1 \text{ maj 3rd} + 2\text{ octave}\\

&= 2 \text{ fifths} + \text{maj3} - \text{octave}\\

&= \text{some kind of tritone}

\end{align*}

$$

<iframe width="560" height="330" src="https://xenpaper.com/#embed:(1%2F2)(env%3A3096)%7Br220hz%7D%0A1%2F1%0A%5B1%2F1_3%2F2%5D_%23_%2Bfifth%0A%5B1%2F1_3%2F2_9%2F4%5D_%23_%2Bfifth%0A%5B1%2F1_3%2F2_9%2F4_45%2F16%5D_%23_%2Bmaj3%0A%5B1%2F1_45%2F16%5D%0A%5B1%2F1_45%2F32%5D_%23_-_octave%0A%0A1%2F1_45%2F32_%23_%3D_some_kind_of_tritone" title="Xenpaper" frameborder="0"></iframe>

For the record, _some kind of tritone_ really means there are an infinite number of possible ways to arrive at a 'tritone', or any other interval for that matter. Try to figure out other alternate ways of adding and subtracting intervals to arrive at a different 'tritones', 'thirds' and even 'octaves'.

:::success

#### Assignment 0

- $2/1$: octave

- $3/1$: fifth + octave

- $5/1$: maj 3rd + 2 octaves

Using the above information and what you have learnt so far, construct 3 different octaves, 2 different major thirds, and 2 different minor thirds. Only use the primes 2, 3 and 5. Listen to them in xenpaper and think about the difference between the variants of each interval, and what factors influence which variant to use.

:::

### 4. Simpler ratios between string length $\Leftrightarrow$ Simpler frequency ratios between strings $\Leftrightarrow$ concordant sound.

Demonstration (you can click the `>` buttons on the left column to start playing from that line instead):

<iframe width="560" height="440" src="https://xenpaper.com/#embed:(1%2F2)(env%3A3096)%7Br330hz%7D%0A%23_Bigger_numbers_%3D_more_discordant%0A1%3A2_2%3A3_3%3A4_4%3A5_5%3A6%0A6%3A7_7%3A8_8%3A9_9%3A10_10%3A11%0A11%3A12_12%3A13_13%3A14%0A%0A1%3A2_%23_Octave%0A2%3A3_%23_P5%0A3%3A4_%23_P4%0A4%3A5_%23_Maj_3%0A5%3A6_%23_m3%0A6%3A7_%23_'bluesy'_min3%0A9%3A16_%23_m7%0A16%3A25_%23_aug5%0A32%3A45_%23_aug4%0A13%3A17_%23_septendecimal_sub-fourth" title="Xenpaper" frameborder="0"></iframe>

:::info

Here, the word _concordant_ is used instead of _consonance_. This important distinction is made such that consonance refers to a subjective, culturally-entrained phenomenon with [inconsistent definitions over time](https://www.plainsound.org/pdfs/HCD.pdf), whereas _concordant_ is used to refer to an (attempt to make an) objective measure of how hard it is, physiologically, for our organs to make sense of what we are hearing, regardless of musical cultural entrainment.

:::

## I3. _Why_ simpler ratios $\implies$ concordant sound?

There is no single correct answer that would fit in this article. But here are some places to start. This section is entirely optional, because there really isn't a single correct explanation™, so it can be quite a rabbit hole.

### I3a. The harmonic series

The harmonic series in music is defined to be the set of (positive) integer multiples of a fundamental note's frequency:

$$

H_{f_0} = \{1f_0, 2f_0, 3f_0, 4f_0, \ldots\}

$$

<iframe width="560" height="220" src="https://xenpaper.com/#embed:(2)(env%3A3096)%7Br1%2F3%7D%0A1%2F1_2%2F1_3%2F1_4%2F1_5%2F1_6%2F1_7%2F1_8%2F1%0A9%2F1_10%2F1_11%2F1_12%2F1_13%2F1_14%2F1_15%2F1%0A16%2F1_17%2F1_18%2F1_19%2F1_20%2F1_21%2F1_22%2F1_23%2F1_24%2F1..." title="Xenpaper" frameborder="0"></iframe>

:::info

NOTE: If you're a brass player, maybe even a string player (open/pinch/artificial harmonics etc), you should be intimately familiar with the concept of partials and harmonics as these instruments utilize the naturally occuring harmonic series as part of standard technique. The sequence of notes you get in an 'open' fingering position are more or less the exact same sequence of notes that is being discussed here.

:::

#### Short answer:

These intervals known as harmonics are naturally occuring in anything that resonates with a timbre. We are exposed to lower harmonics very often, where intervals between the 1st to 3rd partials produce intervals like $2:1$ and $3:2$. Whereas, we hardly get to prominently hear the interval between the 73rd and 69th harmonics in isolation (the orbital resonance of Naiad and Thalassa, Neptune's moons), let alone embedded in a very awkward rough timbre, which makes it a very unfamiliar interval.

#### Long answer:

The harmonic series is a fundamental object in music and occurs in any natural phenomenon that involves resonance/periodicity. Learning music without knowing the applications and implications of the harmonic series is like learning a language without the alphabet, or math without numbers.

A single discernable 'musical note' is really a combination of many notes of varying loudness (known as **overtones/partials**) that are all usually related by integer ratio intervals to the bottom most 'fundamental note'.

Here's a saw wave timbre being constructed by many sine wave partials according to the harmonic series:

<iframe width="560" height="315" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/K3D1fPjWAnc?start=20" title="YouTube video player" frameborder="0" allow="accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture" allowfullscreen></iframe>

When a resonant body is struck, it will not only produce the 'base frequency' our ears instinctively hear as the 'note', but numerous other frequencies would be present in the sound, which we won't perceive as individual pitches but as 'timbre' instead. Most of the time, western instruments have overtones that coincide with the harmonic series.

For example, harmonics of the human voice is what allows us to distinguish between vowels even though we are singing/vocalizing the exact same 'fundamental note'. Different vowels = different timbre = different amplitudes/parities/types of harmonics present:

<iframe width="560" height="315" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/oWmj73Ttp4E?start=20" title="YouTube video player" frameborder="0" allow="accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture" allowfullscreen></iframe>

And here is a visual example of how the harmonic series can manifest in any natural physical phenomenon that can be modelled by standing waves, like a vibrating rope or compressions and rarefactions through the air

<iframe width="560" height="315" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/PVX4V5Adbzk?start=20" title="YouTube video player" frameborder="0" allow="accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture" allowfullscreen></iframe>

Through the Fourier transform/Fourier series you can reconstruct any periodic wave/function using only using sums of sine/cos waves with varying amplitudes and related by an integer multiple of a base frequency. That is, every musical timbre can be represented as a combination of harmonics.

Every sound perceived by the ear is the result of air pressure stimuli causing resonances in individual hair cells of the [basilar membrane](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Basilar_membrane) that essentially performs a [fourier analysis](https://somethingmarvelousblog.wordpress.com/2017/05/10/how-we-hear-or-an-introduction-to-fourier-analysis/) on the input stimuli.

Just because it's cool, here's a nice example of reconstructing an image using only 'harmonics':

<iframe width="560" height="315" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/r6sGWTCMz2k" title="YouTube video player" frameborder="0" allow="accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture" allowfullscreen></iframe>

**Back to answering the main question.** Nature is full of resonances that coincide with the harmonic series, and the lower partials (smaller integer multiples) are more ubiquitous, perhaps because of the [Strong Law of Small Numbers](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Strong_law_of_small_numbers), or that less energy is required for lower frequency oscillation, or whatever other reason.

To give a celestial example, Jupiter is being orbited by moons Ganymede, Europa, Io in a $1:2:4$ resonance. Those are harmonics and Europa and Io correspond to 1 octave and 2 octaves above Ganymede respectively.

The fact that we are so used to lower partials having prominince in the sound could be used to naively justify why interval ratios with lower numbers simply sound 'easier' on the ears, just by instinctive familiarity of those intervals appearing in naturally occuring sounds.

:::info

NOTE: the importance of audiating, recognizing and singing harmonics cannot be understated. It is a natural step to take to develop an acute sensitivity for concordance/discordance and intonation, which can improve your ears ability to transcribe and audiate colours and voicings.

Once you are familiar with the harmonic series, you should be able to identify very prominent partials and/or justly-tuned intervals in the sound of birds, frogs, crickets, wind, car engines, laptop fans, hairdryers, washing machines, coffee grinders, pumps, and your voice. You should find that most of these sounds wouldn't prominently feature intervals past the 16th harmonic.

Here are some golden resources:

<iframe width="560" height="315" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/CCC_WvEfeZE?start=20" title="YouTube video player" frameborder="0" allow="accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture" allowfullscreen></iframe>

<iframe width="560" height="315" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/hDLhe-NkH2A?start=20" title="YouTube video player" frameborder="0" allow="accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture" allowfullscreen></iframe>

<iframe width="560" height="315" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/HP0iotICL7k?start=20" title="YouTube video player" frameborder="0" allow="accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture" allowfullscreen></iframe>

:::

### I3b. Euler's _Gradus Suavitatis_ ("degree of pleasure")

In summary, Euler theorizes that consonance is the result of pitches that 'beat together' often, versus those whose 'beats' rarely coincide. For example, an octave dyad (two-note chord) is $2:1$, meaning, for every 2 times the higher frequency 'beats', the lower frequency will beat in tandem-ish 'once'. One can calculate how rarely any number of frequencies will beat together using the [least common multiple](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Least_common_multiple) function. The greater the LCM/gradus suavitatis between two frequencies, the less often two pitches will beat in tandem with respect to a hypothetical lowest-common-denominator time grid.

<iframe width="560" height="315" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/B6Dvfv_ASVg" title="YouTube video player" frameborder="0" allow="accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture" allowfullscreen></iframe>

:::warning

*Disclaimer*: in the video above, it is said that harmonic dualists (people who believe major and minor triads are fundamentally equally consonant) base their theory on the fact that the gradus suavitatis score of the major triad $4:5:6$ and minor triad $10:12:15$ are both 60 (i.e. $\text{lcm}(4, 5, 6) = \text{lcm}(10, 12,15) = 60$).

However, applying the LCM function on 3 or more notes means you are calculating how often **all three or more** of the notes will finally beat all together, but it doesn't account for how often two pitches (or a subset of the pitches) would beat in tandem with respect to the frequency of other pitches present. We experience the minor triad with a completely different sonority compared to a major triad, so there's definitely something off about this one.

Empirically speaking, a [$4:5:6$ polyrhythm](https://poly.ozieblowski.dev/?lengths=1&repeats=0&swings=0&ratios=4a5a6&subdivides=1&offsets=0&bpm=100)/chord is much easier to conceive than [$10:12:15$](https://poly.ozieblowski.dev/?lengths=1&repeats=0&swings=0&ratios=10a12a15&subdivides=1&offsets=0&bpm=30)

Also, the tuning system we're going to discuss (12ED2) does not use fractional ratios and use irrational exponents of the 12th root of 2 instead (n semitones = $2^{n/12}/1$ interval 'ratio')

Nice idea and simple, but perhaps a little too simple to be an accurate model for anything more than the basic dyadic intervals.

:::

### I3c. Plomp, Levelt/Sethares [_Critical bandwidth_](https://www.mpi.nl/world/materials/publications/levelt/Plomp_Levelt_Tonal_1965.pdf)

Builds upon the idea that discordance stems from the basilar membrane (pitch-discerning part of the ear) not being able to make out individual notes that are too close in pitch. The interval threshold is known as the 'critical band', which blurs the line between two distinct notes, and two notes that are unison, or almost-unison but 'phasing' (the warbling sound when two voices are singing the same note but not perfectly in tune), such that the audio cortet cannot discern if it is the former or the latter. This phenomenon is known as **roughness**.

(Turn volume down)

<iframe width="560" height="315" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/63SmqMprwUU" title="YouTube video player" frameborder="0" allow="accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture" allowfullscreen></iframe>

By this metric, any two sine waves that is sufficiently far enough apart can be infinitely concordant, no matter what 'interval' they spell. However, since most instruments and naturally occuring sounds contains overtones, we also need to account for interactions between frequencies of the overtones.

[This web app by chromatone](https://chromatone.center/practice/sound/dissonance/) is really good for exploring the roughness experienced different intervals within an octave for both harmonic saw and sine timbres.

Note that, according to this theory, if a musical culture develops around an inharmonic timbre instead of harmonic timbres (like in the european classical tradition), then the definition of 'consonance' would evolve to be very different from the 'simple ratios' of contemporary western music.

Such a musical culture exists in the form of _Gamelan_. This video uses critical band/roughness theory to make a connection between the inharmonic timbre of Gamelan instruments and the xen/microtonal slendro/pelog scales being employed

<iframe width="560" height="315" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/ksX-saQVL40" title="YouTube video player" frameborder="0" allow="accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture" allowfullscreen></iframe>

The [xentonal synthesize/new tonality lab](https://newtonality.net/lab) provides a useful interface for exploring the critical bandwidth roughness curves of non-harmonic timbres. Here is a video detailing its use:

<iframe width="560" height="315" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/4d8HXmHtPeY" title="YouTube video player" frameborder="0" allow="accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture" allowfullscreen></iframe>

### I3d. Gestalt Theory/Psychology

The idea that fusion of stimulus perception, psychoacoustic, physiological and cognitive processes give rise to music cognition. This is very trivially true, but the hard part is modelling exactly what each process is doing and figuring out how to get everything to work together. There isn't a single universally accepted way to 'combine' different metrics/models that measure concordance or 'musicality', but we can learn and model as much phenomenon as possible to construct a good-enough model for consonance.

This article is an example of combining some aspects of discordance measure to form a gestalt metric: https://spj.sciencemag.org/journals/research/2019/2369041/

There are numerous psychoacoustic phenomenon that one should be aware of, and this series on youtube is pretty good resource to get started:

<iframe width="560" height="315" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/OiW8gzBGz1A" title="YouTube video player" frameborder="0" allow="accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture" allowfullscreen></iframe>

And here's Diana Deutsch's lecture, who succintly summarizes applicable psychoacoustic phenomena

<iframe width="560" height="315" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/pBeDn8XHhKU" title="YouTube video player" frameborder="0" allow="accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture" allowfullscreen></iframe>

In my opinion, the psychoacoustic phenomena that can be applied directly to the context of western tonal music theory would include:

- [Short term pitch memory](https://deutsch.ucsd.edu/psychology/pages.php?i=209)

- [Combination tones](https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=73_CiAYX00k&ab_channel=AdamNeely)

- Virtual fundamental (modelled by harmonic entropy in the next section)

- Critical bandwidth roughness (previous section)

- General audition, https://academic.oup.com/book/2559

- Rhythmic entrainment:

<iframe width="560" height="315" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/dtL6Go6pi5w" title="YouTube video player" frameborder="0" allow="accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture" allowfullscreen></iframe>

### I3e. [Harmonic Entropy](https://en.xen.wiki/w/Harmonic_entropy)

Measures concordance by evaluating 'how confused your brain is' when hearing a polyphonic sound.

You would probably have noticed a subtle, lower note while playing around with different pitches in the chromatone web app, or when two very high pitched squeals with different notes form a magic third lower note that makes you feel like you have suffered from permanent hearing damage. (This is known as the [tartini/helmholtz/sum-difference/combination](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Combination_tone) tone phenomenon)

Harmonic entropy deals with measuring the ability/probability of the ear being able to fuse discrete pitches into a 'virtual pitch' with a lower fundamental, which works like combination tones in the sense that a lower/higher pitch is magically evoked that has the frequency of some linear combination of the remaining frequencies present, but instead of any arbitrary lower/higher tone, this tone can function as a 'fundamental frequency', of which all actually present notes are now 'harmonics' of. This video demonstrates the phenomenon better than any words can, so:

<iframe width="560" height="315" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/0Y4-NQQ6hAY" title="YouTube video player" frameborder="0" allow="accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture" allowfullscreen></iframe>

Harmonic entropy thus is a metric of how able is the brain to make sense of discrete pitches in stimuli as an overarching, composite sound versus individual unrelated notes. In summary, it does this by taking a statistical/information theoretical approach on what possible intervals the brain could possible be identifying the input stimuli as, and seeing how statistically probable is any one interpretation over the other by measuring [entropy](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Entropy_(information_theory)).

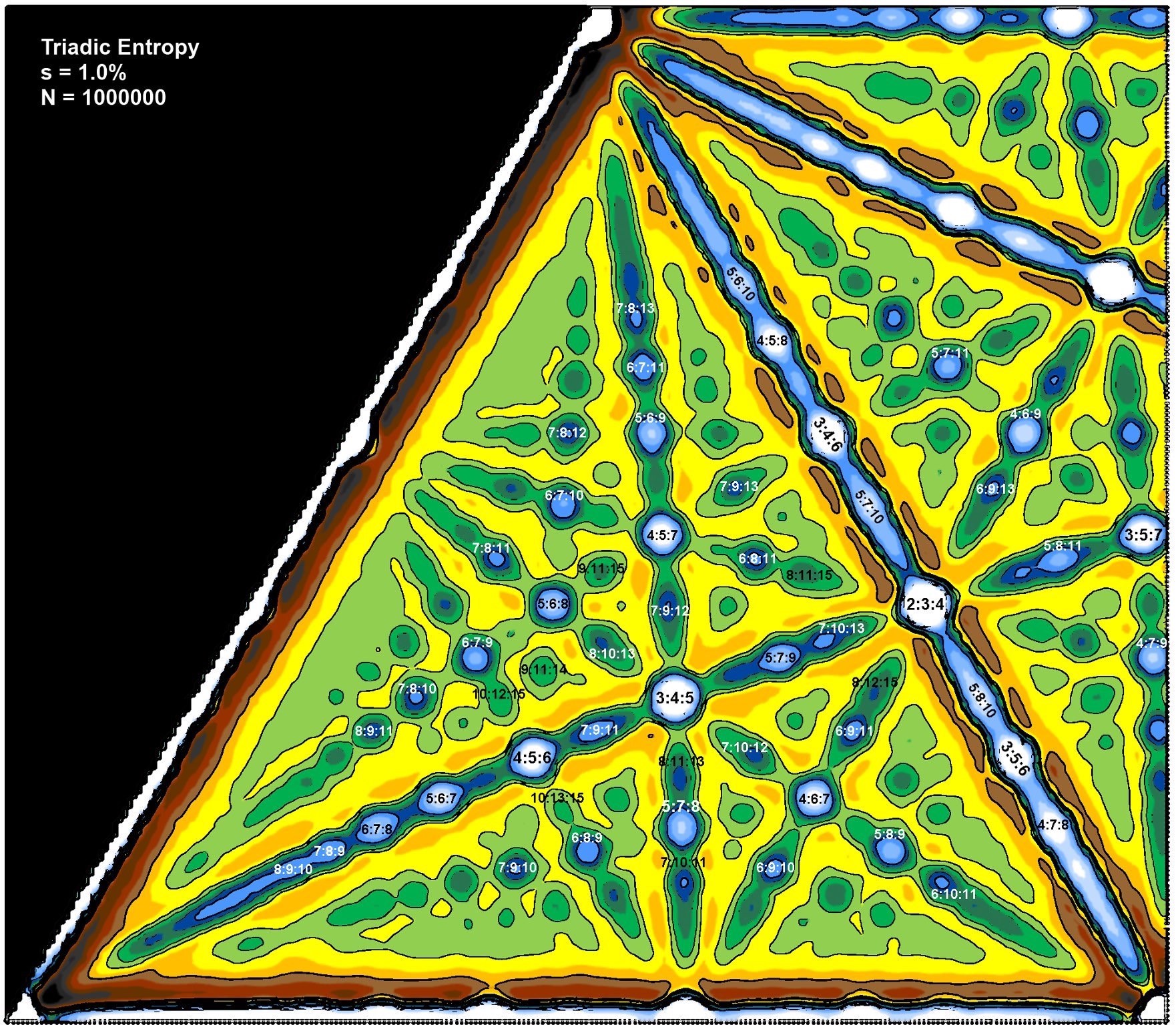

This is beginning of the deep end and it's hard to find accessible layman resources on how exactly to begin calculating this. Nevertheless, you can trust [Mike Battaglia's calculator](http://www.mikebattagliamusic.com/HE-JS/HE.html) and this image:

### I3f. R̴̛͓̰̗ą̸̰̗̈t̸̯̖̭̄i̷̛̳̙͇͊̌͝ò̶̡͖̘̊n̶̨̫͒̍̍a̶̻̕l̵̨̹̊ ̴̳̩̅̉͜p̴̟͍̥̝͒o̵͔̿͆͝͝i̷͈̽ǹ̶͈̫͗͜͜t̵̢͖̣̀̈́s̴̛͇̽̾͆ ̵͚̯̄̆̆o̶̡͓͔̍n̶͈̮͍̉ ̷̤̘̽̽̈́̚ȃ̴̧̤ ̴͍̜̮͐G̸̰͉̙͇͊̔r̴̨͕̝͆͋́a̶̮̾̈́s̶̞̤͆̋s̶̩̬̫̳̀̂́m̶͈͇̒ả̷̹̦̦͘ṉ̶̡̾̂n̴̪̮̊i̸̜̳͑͝a̸̪͈̱̲̍̐n̸͇̪͋̇ͅ

Instead of relying on empirical observation, you could use [group-theoretic](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Group_theory) means to reason about the symmetries that naturally arise in [subgroups](https://mathworld.wolfram.com/NormalSubgroup.html) of the [infinite-dimensional](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grassmannian) [just intonation lattice](https://en.xen.wiki/w/Just_intonation_subgroup), then [temper](https://en.xen.wiki/w/Wedgies_and_multivals) these using [rank-n](https://en.xen.wiki/w/Rank_and_codimension) [vals](https://en.xen.wiki/w/Val) in [defactored hermite form](https://en.xen.wiki/w/Normal_lists#Defactored_Hermite_form) to create a (n-1) dimension [fokker block](https://en.xen.wiki/w/Fokker_block) and find [homomorphisms](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Homomorphism) preserving/between a particular [cycle](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cyclic_permutation) in a [finite abelian group](https://groupprops.subwiki.org/wiki/Finite_abelian_group) of the [MOS](https://en.xen.wiki/w/MOS_scale) set [under](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Closure_(mathematics)) multiplication, and that of [multilinear mappings](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Multilinear_map) of the [geometric products](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Geometric_algebra) of [pergen](https://en.xen.wiki/w/Pergen) [k-vectors](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Multivector) of [grade](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Blade_(geometry)) (n-1) to calculate the [tenney-optimal tuning](https://en.xen.wiki/w/TOP_tuning) of a temperament that can, at the same time, maximize [isometry](https://ianring.com/musictheory/scales/#spectrum) and minimize the [exterior product](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Exterior_algebra) which allows the performer/composer to maximize expression and minimize cognition, and use the [image](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Image_(mathematics)) of $\sigma + it$ under the [Riemann $\zeta$ function](https://en.xen.wiki/w/The_Riemann_zeta_function_and_tuning#Zeta_EDO_lists) to find optimal supersets that can approximately support the [dual](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spectrum_of_a_C*-algebra) [join](https://rigidgeometricalgebra.org/wiki/index.php?title=Join_and_meet) of 2-blades while maximizing [telicity](https://en.xen.wiki/w/Telicity). Yeah.

The cool part about is how just a few 'common-sense' axioms can construct a rigorous idea of useful tunings and concordance from an a priori standpoint. I.e., the nature of how numbers relate to other numbers, how geometry just is, and how the number of symmetry preserving permutations given some structure is always fixed given the same conditions. All of which would make [mathematical realists](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Philosophy_of_mathematics#Major_themes) happy.

For more info, read the work of [Gene Ward Smith](https://en.xen.wiki/w/Gene_Ward_Smith), [Paul Erlich](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paul_Erlich), [Mike Battaglia](https://en.xen.wiki/w/User:Mike_Battaglia), [Flora Canou](https://en.xen.wiki/w/User:FloraC), Scott Dakota, [Joe Monzo](http://tonalsoft.com/default.aspx), [Dave Keenan](https://en.xen.wiki/w/Dave_Keenan), [George Secor](https://en.xen.wiki/w/George_Secor), [Steve Martin](https://soundcloud.com/ninly) et al.

### I3g. Music Theorym 1.1: Static Concordance-Discordance

:::success

To conclude this subsection, we shall state the first _music theorym_ of this article:

> The Concordance-Discordance spectrum is a heuristic ranking system for intervals, colors, chords, textures; such that sounds are said to have 'higher concordance'/'lesser discordance' if they are easier for the brain to process, internalize, regurgitate, audiate and cognize.

>

> Assuming an instrument/sound with a harmonic timbre which does not deviate too far from the harmonic series, intervals with simpler ratios or closely approximating simple ratios are generally more concordant than that of complex ratios.

:::

To dive even deeper, here are some recommended resources

- [A History of 'Consonance' and 'Dissonance' (James Tenney)](https://www.plainsound.org/pdfs/HCD.pdf)

- [Height functions](https://en.xen.wiki/w/Height)

- [Harmonic entropy](https://en.xen.wiki/w/Harmonic_entropy)

-----

## I4. The time dimension

According to the previous section, we can now agree that the major triad is a consonant structure.

So, here's an example consisting of only major triads. In just intonation no less.

<iframe width="560" height="350" src="https://xenpaper.com/#embed:(3)%0A4%3A5%3A6%0A%7Br7%2F6%7D3%3A4%3A5%0A%7Br9%2F13%7D4%3A5%3A6%0A%7Br9%2F7%7D5%3A6%3A8%0A%7Br10%2F11%7D3%3A4%3A5%0A%7Br13%2F10%7D4%3A5%3A6%0A%7Br7%2F5%7D3%3A4%3A5%0A%7Br11%2F16%7D4%3A5%3A6%0A%7Br5%2F7%7D5%3A6%3A8%0A%7Br31%2F25%7D3%3A4%3A5%0A%7Br32%2F33%7D4%3A5%3A6%0A%7Br7%2F6%7D3%3A4%3A5%0A%7Br9%2F11%7D4%3A5%3A6%0A%7Br9%2F7%7D5%3A6%3A8%0A%7Br4%2F5%7D3%3A4%3A5%0A%7Br29%2F17%7D4%3A5%3A6" title="Xenpaper" frameborder="0"></iframe>

Everything you just heard are bona fide major triads. So why doesn't it sound like the product of a consonant object? Instead, it reeks of randomness, atonality, or god forbid, _chromaticism_ (the most useless, indescriptive word in music theory). Whatever the case, it doesn't appear to be 'tonal', whatever that means.

If we slow it down, the reduced rate allows us to take in the color of the chords individually and now it starts to make a little more sense. However you couldn't really say that these chord changes are _predictable_. The consonance of each chord only stands alone, and only works in the context of itself.

<iframe width="560" height="220" src="https://xenpaper.com/#embed:(1%2F3)4%3A5%3A6%0A%7Br7%2F6%7D3%3A4%3A5%0A%7Br9%2F13%7D4%3A5%3A6%0A%7Br9%2F7%7D5%3A6%3A8" title="Xenpaper" frameborder="0"></iframe>

Finally, this example should sound a lot more familiar, and should give a sense of _resolve_ at the end.

<iframe width="560" height="315" src="https://xenpaper.com/#embed:(1%2F3)4%3A5%3A6%0A3%3A4%3A5%0A%7Br15%2F16%7D5%3A6%3A8%0A%7Br16%2F15%7D4%3A5%3A6" title="Xenpaper" frameborder="0"></iframe>

What gives? All the examples were just major triads in several inversions.

Perhaps you may guess:

- The last example is 'in tune', and the first two were not.

- The last example sticks to a scale, and the first two didn't.

However, the last example was just as 'out of tune' as the first two are. Since all these examples are in just intonation, none of these notes except $A=1/1=440\text{hz}$ can be found on the piano.

And what is a scale really? Why does staying in a scale matter, and why don't we see the first two examples as staying to a scale which just has more notes -- what's so special about _this scale_?

The goal of subsections I4 (on semitone cancellation conjecture) and I5 (on the etymology of chords) is to give you the ability to rigorously and confidently answer these questions the next time these intrusive epistemological and ontological thoughts about music hinder you or your buddies' consciousness.

The answer revolves around your short term memory, and the fact that music encodes information in a spatial tangible object, but also through the 'dimension' of time. Here goes:

### I4a. Hearing color

Perhaps this should sound familiar to you:

<iframe width="560" height="210" src="https://xenpaper.com/#embed:(2)_1%2F1_5%2F4_3%2F2_15%2F8_27%2F16_3%2F2_5%2F4_1%2F1_10%2F9_4%2F3_30%2F18_2%2F1_15%2F8--." title="Xenpaper" frameborder="0"></iframe>

Or this:

<iframe width="560" height="325" src="https://xenpaper.com/#embed:(2)_%7Br261.63hz%7D%0A1%2F1_5%2F4_3%2F2_2%2F1_5%2F2_3%2F2_2%2F1_5%2F2%0A1%2F1_5%2F4_3%2F2_2%2F1_5%2F2_3%2F2_2%2F1_5%2F2%0A1%2F1_10%2F9_30%2F18_20%2F9_8%2F3_30%2F18_20%2F9_8%2F3%0A1%2F1_10%2F9_30%2F18_20%2F9_8%2F3_30%2F18_20%2F9_8%2F3%0A15%2F16_9%2F8_3%2F2_9%2F4_8%2F3_3%2F2_9%2F4_8%2F3%0A15%2F16_9%2F8_3%2F2_9%2F4_8%2F3_3%2F2_9%2F4_8%2F3%0A1%2F1_5%2F4_3%2F2_2%2F1_5%2F2_3%2F2_2%2F1_5%2F2%0A1%2F1_5%2F4_3%2F2_2%2F1_5%2F2_3%2F2_2%2F1_5%2F2" title="Xenpaper" frameborder="0"></iframe>

Or this:

<iframe width="560" height="290" src="https://xenpaper.com/#embed:(2)_%7Br261.63hz%7D%0A1%2F1-.9%2F8_5%2F4-.1%2F1%0A5%2F4-1%2F1-5%2F4--.%0A9%2F8-.5%2F4_4%2F3_4%2F3_5%2F4_9%2F8%0A4%2F3---....%0A5%2F4--4%2F3_3%2F2-._5%2F4%0A3%2F2-5%2F4.3%2F2-.." title="Xenpaper" frameborder="0"></iframe>

Or just sing any melody you know of the top of your head.

Chances are, as you're singing or recalling a familiar melody, it is not merely the melody that goes through you mind. Depending on how familiar you are with that tune, you should be able to feel what color the notes have, perhaps what harmony goes under it, which melodic phrases sound like 'questions', and which ones are their 'answers'.

Why so? You are only singing one note at a time, and these examples are purely monophonic, there are no chords nor accompaniment, yet you are experiencing the fundamental element of tonal harmony. You are experiencing changes in color --- which is to say, the experience of tension and resolution.

What is the cause of this tension and resolution? There's only one note occuring at any one time, so what exactly do these notes 'conflict' with; what do these notes 'resolve' with respect to? The tonic?

### I4b. What is the 'tonic'

Not the first degree of a scale. Here, tonicity refers to the character of 'resolution'.

Firstly, listen to silence. Do not audiate anything. What is the tonic? If you have perfect pitch, you may answer with your favorite note/chord while audiating it, but for now, ignore that you have perfect pitch and pretend that you really are not able to conjure up any sound which you are confidently able to name.

The correct answer™: _there is no tonic_.

What can be judged to be resolved or dissonant if there is no sound? And if so, perhaps the ether of silence itself is the only true tonic, since we are inherently familiar with [_anahata_](https://www.semantic-danielou.com/semantic-danielou-36/ahata-anahata-semantic-danielou-36/), the sound of no sound.

Now listen to this:

<iframe width="560" height="150" src="https://xenpaper.com/#embed:420.69hz-----" title="Xenpaper" frameborder="0"></iframe>

What note is that? Well, it's not on any recently tuned piano, that's for sure. It doesn't matter what that note is called. But from now on until the next sound example, _this will be the tonic_.

Even after it is gone, it lingers, and most people probably would still be able recall and sing it within a small margin of error after a few seconds after it is gone.

Anything else you hear will be heard with respect to this note, until something else comes along and distracts you from that note and you forget what it was. You can only forget the sound through conscious agency or some very convincing new sound/thought.

Be distracted by this very convincing new sound:

<iframe width="560" height="150" src="https://xenpaper.com/#embed:420.69hz---_400hz---" title="Xenpaper" frameborder="0"></iframe>

Which is the tonic? The first, second, both, neither?

The correct answer™: everything except both at the same time.

It depends on what music you like, it depends on the musical culture that you're brought up with. Perhaps european classical music theory has informed you that anything that moves downwards is like a 'sigh' which means that the downwards motion implies that the lower note is resolved.

Perhaps your neocortex is telling you that the former of the two is always more important, or depending on the language you speak, the latter, and thus which ever is more important becomes the tonic, and the other note begs to be resolved.

Perhaps you still have the sound of the first note in your head and you have made it a mental note to regard this as the tonic, and for that reason the former is not the tonic and thus unresolved.

Whatever the case, are _both_ the notes simultaneously tonic? Could you hear them on perfectly equal footing, with perfectly equal function, without subjective preference or unbalanced directed consciousness for one or the other? Could the former note truly substitute the role of the other without changing the musical function and application of the two notes? Most probably the answer is no, unless you love Morton Feldman/Messiaen or are already a xen music enjoyer (then you really don't need to be reading this article).

Finally, here are two more notes:

<iframe width="560" height="150" src="https://xenpaper.com/#embed:(1%2F2)_1%2F1_3%2F2" title="Xenpaper" frameborder="0"></iframe>

Which is the tonic? First, second, both, neither?

Here's the same two notes in different octaves, different order and different transpositions:

<iframe width="560" height="315" src="https://xenpaper.com/#embed:(1%2F2)_%0A1%2F1_3%2F2..%0A%7Br2%2F3%7D3%2F2_2%2F1..%0A%7Br3%2F2%7D3%2F2_1%2F1..%0A%7Br3%2F2%7D1%2F1_3%2F2..%0A%7Br8%2F9%7D3%2F2_1%2F1..%0A%7Br3%2F4%7D3%2F2_2%2F1.." title="Xenpaper" frameborder="0"></iframe>

Could you consistently attribute the property of 'tonicity' to either $3/2$, and have $1/1$ & $2/1$ always sound like the 'unresolved' note? Or vice versa, where the $1/1$ & $2/1$ was always tonic and the $3/2$ is not. No matter the transposition or order of the notes?

Probably not. For example, if you heard the first 1/1 as tonic, then the 3/2 of the second phrase would initially be heard as 'resolved' note as well.

Furthermore, here's yet another example using only $1/1$ and $3/2$ (which for brevity, is notated as '0' and '7' semitones away from the tonic)

<iframe width="560" height="315" src="https://xenpaper.com/#embed:0_7_7_0_7_0_0_7%0A7_0_0_7_0_7_7_0%0A7_0_0_7_0_7_7_0%0A0_7_7_0_7_0_0_7%0A7_0_0_7_0_7_7_0%0A0_7_7_0_7_0_0_7%0A0_7_7_0_7_0_0_7%0A7_0_0_7_0_7_7_0" title="Xenpaper" frameborder="0"></iframe>

Which one feels more tonic?

Here is the same pattern but transposed down a fifth.

<iframe width="560" height="315" src="https://xenpaper.com/#embed:%7Br2%2F3%7D%0A0_7_7_0_7_0_0_7%0A7_0_0_7_0_7_7_0%0A7_0_0_7_0_7_7_0%0A0_7_7_0_7_0_0_7%0A7_0_0_7_0_7_7_0%0A0_7_7_0_7_0_0_7%0A0_7_7_0_7_0_0_7%0A7_0_0_7_0_7_7_0" title="Xenpaper" frameborder="0"></iframe>

Did you still stick to hearing the same tonic? What even is the 'same' tonic? Same with respect to absolute pitch? Or same with respect to relative scale degree in the new key?

Yet still, try playing both exerpts at the same time.

The above example features something mathematicians, game theorists, and cryptographers should find familiar: the [Thue-Morse sequence](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thue%E2%80%93Morse_sequence), also known as the 'fair share sequence'.

Here is a nice video about it by Matt Parker:

<iframe width="560" height="315" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/prh72BLNjIk" title="YouTube video player" frameborder="0" allow="accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture" allowfullscreen></iframe>

Lets draw from the above analogy of a turn-based game like connect-4/tic-tac-toe/hackenbush/chess and treat the above examples like a game of "which note is more important" fought out between the two notes:

We assume that the first note heard will always have more promimenence than the second (or vice versa, it doesn't matter). Even if we were to toggle between the two equally like `0 7 0 7 0 7 ...`, the first of every two will still be 0 and there will be a bias towards `0` over `7`.

So for the next iteration, we need to reverse the order of the notes' appearances. If a sequence begins `0 7`, then we follow it by `7 0` to make it fair. But even if we were to iteratively repeat `0 7 7 0 0 7 7 0 ...`, a 4-element pattern emerges which would still give increased prominence to either note.

So, the way around this is to employ the fair share sequence is to create the most fair winning chances for either note to win the title of 'Tonic'.

Even then, what did you hear as tonic? Perhaps take a break and touch some grass, come back to the examples in reverse order (play the second fair-share sequence first), and see if you've changed your mind. If you did, why? If not, was there some musical culture that you are heavily entrained towards that could be reason why you've always chosen the same answers, despite giving either note 'equal winning chances'? What does that culture say about deciding which one is the tonic? Why did it say so?

### I4c. What tonicity is/isn't.

Now that your conception of tonicity is completely broken. Let us gather our thoughts and reconstruct:

There is simply no way of attributing the tonic to _one_ note. There is no such thing as a one-note tonic. In fact, the idea that 'tonic' represents a 'fundamental note' is flawed from the get go. The [etymology](https://www.etymonline.com/word/tonic) of the word tonic (in the musical context) simply is 'tone'-'ful'. Tonic --- something that has the characteristics of a tone. If you want to go back even further, it would come from [τόνος](https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/%CF%84%CF%8C%CE%BD%CE%BF%CF%82#Greek) which simply means... a rope, a chord, a tone, string tension, a string. Going back even further, it comes from the proto-indo-european root word [ten-](https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/Reconstruction:Proto-Indo-European/ten-), which means 'to stretch', as in 'tension'. Remember the monochord at the start of this article?

The idea of 'tonic' being used to mean the one and only 'Do' note is a result of viennese classical analysis being used to analyse its own music, and elides much of the original essense of what the word really is.

The full exposition on the origin of the 'tonic' concept is beyond the scope of this article, but here are a few good places to start:

- [Greek genera](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Genus_(music)) an etymological parent of Byzantine/Persian/Arabic/Turkish/Gregorian/Guidonian musical constructs

- [Book of Later Han](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Book_of_the_Later_Han) detailing the constructions of scales and math for astronomy within the Sino etymological context.

- [Macam](https://www.maqamworld.com/en/index.php) which has very clear influences from the genera system

- The origin of Raag and the 22 shrutis (discussed prior)

- [Guidonian hand](https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IRDDT1uSrd0&ab_channel=EarlyMusicSources)

- [Clausula (16th/17th century cadences voice movements)](https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jaCRUdxTRSM&ab_channel=EarlyMusicSources)

All of which has ultimately influenced the modern western definition of 'tonicity'.

**After diving into all that**, or if you're lazy you can take my word for it, you should be able to conclude that tonicity is nothing to do with Viennese functional harmony, Schenkerian analysis, polyphony, nor having a single 'root note' to hear things with respect to.

Tonicity is a **set of sets**. There is set of notes that the ear is presently hearing as input stimuli, a set of notes that is currently being consciously processed and audiated, a set of notes that only exists in short term memory, and a set of notes in the subconscious extrinsic physiological factors as the result of cultural entrainment.

Simply put, tonicity is whatever the ear can 'feel at home' with. It could be no notes, one notes, or many notes. It is a byproduct of real-time stimuli experienced through physiological filters, and short and long term memory recall of what 'phrases' to expect, what 'beat' and 'tonic set' to feel, and what 'cliches' and common 'vocabulary' exists in that particular musical culture to draw from so that musical idioms can be used for succint and efficient expression.

Some academic sources coin the term 'tonic space'/'tonal space' to convey the idea that tonicity is not a single note but a cloud/area/spiral/segment of pitches where the characteristic of tonicity is prominent. For the purposes of this article, this idea will simply be referred to as the '_tonic_' or '_tonic set_'. (Also helps prevent an argument with those that believe a 'space' must fulfill right identity, associativity, transitive free actions, injective translations blah blah... music is not a hard science blah blah...)

One thing is clear though, no matter how hard you try, this (as in, the sum of all these notes concurrently) cannot be the tonic:

<iframe width="560" height="150" src="https://xenpaper.com/#embed:23%3A24%3A28%3A29%3A30%3A31%3A33%3A37------" title="Xenpaper" frameborder="0"></iframe>

In order to fulfil the requirements for being a 'tonic', the set of notes must:

- be easily recallable in the real-time context

- be easily audiatable (internally hear-able using willpower) in real-time context

- yield a sense of 'resolve' when resolved to

- be structurally strong enough to withstand other aural information being hurled at the listener for at least one second.

:::success

Note how this definition of tonicity is an instantaneous one. The 'tonic' is a constantly morphing object which can be different at every unique point in the song. So, when we talk about 'tonic', it really refers to the 'current tonic' with respect to this instantaneous point in time.

:::

The above example fails all of that, except the third one, because there are spectral ways to use such a chord as a partial resolution.

However, let's try to use that ridiculous chord anyways:

<iframe width="560" height="190" src="https://xenpaper.com/#embed:4%3A5%3A6---%0A23%3A24%3A28%3A29%3A30%3A31%3A33%3A37---%0A4%3A5%3A6---" title="Xenpaper" frameborder="0"></iframe>

Now, that sounds permissible. Perhaps even musical. Because that unnamable chord (_there are enough names in music, please do not make more_), was prefaced by, then resolved to _a_ tonic. In this particular case, a major triad was arbitrarily chosen to be the tonic. Anyone in the western music tradition will know what a major triad is, so:

- it is easily identifiable and recallable in real-time,

- it is easily audiatable,

- yields a strong sense of resolve just because it is a consonant structure (as earlier discussed),

- and is structurally strong enough to stay in the memory in spite of the temporary digression to the ridiculous unnamable chord.

### I4d. Answering the main question: The origin of functional/tonal harmony

So why can we hear functional harmony/color/tension-release in those examples at the start despite them being only monophonic excerpts without accompaniment?

Let us take our first example melody --- [_Mr. Sandman - The Chordettes_](https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CX45pYvxDiA&ab_channel=RiulDoamnei)

<iframe width="560" height="220" src="https://xenpaper.com/#embed:(2)_1%2F1_5%2F4_3%2F2_15%2F8_27%2F16_3%2F2_5%2F4_1%2F1_10%2F9_4%2F3_30%2F18_2%2F1_15%2F8--.%0A1%2F1_5%2F4_3%2F2_15%2F8_27%2F16_3%2F2_5%2F4_1%2F1_10%2F9_4%2F3_30%2F18_2%2F1_15%2F8--." title="Xenpaper" frameborder="0"></iframe>

First, we apply our new axioms of tonicity. Any note or set of notes that can be easily recalled and audiated at any instantaneous point in time will fulfil the 'tonic' characteristic.

The initial 'tonic' at the time of the first note is obviously just the first note itself.

Then, we add $5/4$ (major third) to the set of notes. Since those in the western tradition are familiar with this note appearing in the context of $1/1$ (that is, the interval between $5/4$ and $1/1$ being a major third), thus it doesn't hinder the ability to recall nor audiate the initial $1/1$, and we can append $5/4$ to our 'set of tonics'. Same goes for $3/2$.

However, $15/8$ may be up for debate. Some may say that $15/8$ is highly discordant with respect to $1/1$, and thus the presence of this new note will cause the listener to subconsciously forget the sound of $1/1$. However, others may say that it does not matter because the sound of $15/8$ can be cognized with respect to the existng $5/4$ instead, or that the current structure would equal a major7 tetrad which is a familiar color in post-classical harmony... the list of arguments could go on.

In whatever case, let us assume the most lenient rules which allow for the most number of unique 'tonic sets' possible in 12ED2, which still suffices for this guide and allows us to axiomatically rationalize most of rennaisance harmony and onwards:

### I4e. Music Theorym 1.2: Sesquisharp/Semitone Cancellation Conjecture

:::warning

Disclaimer: these are all just random names I came up with. I couldn't find anything consise online which conveys this idea that I am presenting here, though I found a generative music AI project which came to this conclusion on its own, by modelling tonality as a set of note-probability tuples instead of a binary "Does the current tonality contain note x" question. Sadly I can't remember what the project was called and I can no longer find the paper. Do inform me if you have found anything else online that shares a similar sentiment.

:::

:::success

We are now ready to state the second _music theorym_ of this article:

It is known that we can remember the sounds of pitches. We perceive new stimuli with respect to what we have already heard. The 'tonic set' consists of whatever pitches that the ear is familiar with at a given instantaneous point in time.

We assume all perceived notes are committed to memory, and thus the 'tonic set', and can affect perception of future pitches.

Then, assume the listener instantaneously removes 'tonic' status from an old note only when it is no longer in present stimuli, _and_ only if a new pitch occurs exactly one [sesquisharp](https://www.wikidata.org/wiki/Q18107341) or less from the old note (i.e., ≤1.33~1.66 semitones which is an empirically justified number taken from [Diana Deutsch's Short Term Memory for Tones](https://deutsch.ucsd.edu/psychology/pages.php?i=209)).

The interactions between stimuli and short term memory evokes changes in 'color', regardless if the stimuli is monophonic or polyphonic.

:::

The basis to assume these rules stems from the fact that Diana Deutsch has showed that listeners show an increase in uncertainty of a pitch when trying to recall it after another pitch that was within (66¢ and 166¢) from it was sounded. We can draw from this to mean that the cognizing ear does not consider a prior note to be in the 'tonic set' once a new note within (66¢ ~ 166¢) of the old note is sounded.

We **do not** assume octave equivalence. So a major 7th interval is regarded as a major 7th interval, not an octave shifted min2nd, and thus does not cancel a prior pitch at that interval. This is with the occasional exception where the cognitive dissonance between stimuli and pitch memory is subjectively too intolerable and prolonged for too long, according to a specific musical culture's rules (e.g. using unprepared major 7ths freely in the common practice era is not a good idea). However this exception is very vague and there is no rigorous way to describe this besides learning all the cultural rules and precepts within a musical culture.

Using this rule, let us juxtapose the melody of Mr. Sandman with the modelled 'short term memory' of the 'tonic set' by applying this semitone cancellation.

<iframe width="560" height="315" src="https://xenpaper.com/#embed:(2)_%0A1%2F1%0A%5B1%2F1%5D_%23_A%0A5%2F4_%0A%5B1%2F1%2C_5%2F4%5D_%23_Amaj3%0A3%2F2%0A%5B1%2F1%2C_5%2F4%2C_3%2F2%5D_%23_Amaj%0A15%2F8%0A%5B1%2F1%2C_5%2F4%2C_3%2F2%2C_15%2F8%5D_%23Amaj7%0A27%2F16%0A%5B1%2F1%2C_5%2F4%2C_3%2F2%2C_27%2F16%2C_15%2F8%5D_%23Amaj7(13)%0A3%2F2%0A%5B1%2F1%2C_5%2F4%2C_3%2F2%2C_27%2F16%2C_15%2F8%5D_%23Amaj7(13)%0A5%2F4%0A%5B1%2F1%2C_5%2F4%2C_3%2F2%2C_27%2F16%2C_15%2F8%5D_%23Amaj7(13)%0A1%2F1%0A%5B1%2F1%2C_5%2F4%2C_3%2F2%2C_27%2F16%2C_15%2F8%5D_%23Amaj7(13)%0A10%2F9%0A%5B1%2F1%2C_10%2F9%2C_5%2F4%2C_3%2F2%2C_27%2F16%2C_15%2F8%5D_%23Amaj9(13)%0A4%2F3%0A%5B1%2F1%2C_10%2F9%2C_4%2F3%2C_3%2F2%2C_27%2F16%2C_15%2F8%5D_%23B%5Cm11(%2F5%2C13)%0A30%2F18%0A%5B1%2F1%2C_10%2F9%2C_4%2F3%2C_3%2F2%2C_30%2F18%2C_15%2F8%5D_%23B%5Cm11(13)%0A2%2F1%0A%5B1%2F1%2C_10%2F9%2C_4%2F3%2C_3%2F2%2C_30%2F18%2C_2%2F1%5D_%23B%5Cm11%0A15%2F8-%0A%5B1%2F1%2C_10%2F9%2C_4%2F3%2C_3%2F2%2C_30%2F18%2C_15%2F8%5D--.._%23E9(13)%2FA%0A%0A%23_Don't_assume_tonality_resets%0A%23_after_a_phrase.%0A1%2F1%0A%5B1%2F1%2C_10%2F9%2C_4%2F3%2C_3%2F2%2C_30%2F18%2C_15%2F8%5D_%23E9(13)%2FA%0A5%2F4%0A%5B1%2F1%2C_10%2F9%2C_5%2F4%2C_3%2F2%2C_30%2F18%2C_15%2F8%5D%0A3%2F2%0A%5B1%2F1%2C_10%2F9%2C_5%2F4%2C_3%2F2%2C_30%2F18%2C_15%2F8%5D%0A15%2F8%0A%5B1%2F1%2C_10%2F9%2C_5%2F4%2C_3%2F2%2C_30%2F18%2C_15%2F8%5D%0A27%2F16%0A%5B1%2F1%2C_10%2F9%2C_5%2F4%2C_3%2F2%2C_27%2F16%2C_15%2F8%5D%0A%23_etc...%0A3%2F2-_5%2F4-_1%2F1-_10%2F9-_4%2F3-_30%2F18-_2%2F1-_15%2F8--." title="Xenpaper" frameborder="0"></iframe>

Whew. That wasn't hard, just very tedious. Such is the process of rigorously analysing the 'tonality' at any given point in time.

However, note that some of the 'tonal set chords' predicted by model is a bit off (like the E7 on A), because:

- We are not considering the real song Mr. Sandman with polyphonic pitch stimuli instead of just having a single monophonic melody

- We do not assume cultural rules about where 'wrong' notes implicitly resolve themselves just by convention, like how any listener familiar with music from the western tradition would naturally forget the 1/1 tonic A note on the supposed E7 dominant chord by the time the music gets to that point.

We can further refine the process by using a statistical and temporal-sensitive model (like the AI music generator project, which allows notes to be 'detonicized' if not resounded after a specific time threshold relative to its concordance score), or by regularly looking out for obvious consonant structures where all but one note adhere to a ratio (by using a computational model like harmonic entropy/critical bandwidth like [this 11-limit realtime JI visualizer](https://github.com/euwbah/31edo-lattice-visualiser), which is a project I made to apply a fuller, more general, version of this 'semitone cancellation conjecture').

If we allow for rhythmic and cultural entrainment, we can know that this melody consists of 2 bar of 4-4 time that repeats twice. We can use cultural entrainment to expect a chord change on the 1st beat of a new bar, especially since the 'bottom voice' of the melody shifts up from $1/1$ to $9/8$. This allows the listener to 'detonicize' $1/1$ just by cultural entrainment. That way, $1/1$ is no longer awkwardly a part of the E7 chord, resulting in this instead:

<iframe width="560" height="400" src="https://xenpaper.com/#embed:(2)_%0A1%2F1%0A%5B1%2F1%5D_%23_A%0A5%2F4_%0A%5B1%2F1%2C_5%2F4%5D_%23_Amaj3%0A3%2F2%0A%5B1%2F1%2C_5%2F4%2C_3%2F2%5D_%23_Amaj%0A15%2F8%0A%5B1%2F1%2C_5%2F4%2C_3%2F2%2C_15%2F8%5D_%23Amaj7%0A27%2F16%0A%5B1%2F1%2C_5%2F4%2C_3%2F2%2C_27%2F16%2C_15%2F8%5D_%23Amaj7(13)%0A3%2F2%0A%5B1%2F1%2C_5%2F4%2C_3%2F2%2C_27%2F16%2C_15%2F8%5D_%23Amaj7(13)%0A5%2F4%0A%5B1%2F1%2C_5%2F4%2C_3%2F2%2C_27%2F16%2C_15%2F8%5D_%23Amaj7(13)%0A1%2F1%0A%5B1%2F1%2C_5%2F4%2C_3%2F2%2C_27%2F16%2C_15%2F8%5D_%23Amaj7(13)%0A10%2F9%0A%5B10%2F9%2C_5%2F4%2C_3%2F2%2C_27%2F16%2C_15%2F8%5D_%23B%5C11sus%0A4%2F3%0A%5B10%2F9%2C_4%2F3%2C_3%2F2%2C_27%2F16%2C_15%2F8%5D_%23B%5Cm11(%2F5%2C13)%0A30%2F18%0A%5B10%2F9%2C_4%2F3%2C_3%2F2%2C_30%2F18%2C_15%2F8%5D_%23B%5Cm11(13)%0A2%2F1%0A%5B10%2F9%2C_4%2F3%2C_3%2F2%2C_30%2F18%2C_2%2F1%5D_%23B%5Cm11%0A15%2F8-%0A%5B10%2F9%2C_4%2F3%2C_3%2F2%2C_30%2F18%2C_15%2F8%5D--.._%23E9(13)%0A%0A%23_Since_we_are_taking_into_account%0A%23_phrasing%2C_expect_a_repeated_tonality%0A%23_reset_tonality_to_the_'initial_tonic'.%0A%23_Forget_10%2F9_at_the_'bottom'.%0A1%2F1%0A%5B1%2F1%2C_5%2F4%2C_3%2F2%2C_15%2F8%5D_%23Amaj7%0A5%2F4%0A%5B1%2F1%2C_5%2F4%2C_3%2F2%2C_15%2F8%5D_%23Amaj7%0A3%2F2%0A%5B1%2F1%2C_5%2F4%2C_3%2F2%2C_15%2F8%5D_%23Amaj7%0A15%2F8%0A%5B1%2F1%2C_5%2F4%2C_3%2F2%2C_15%2F8%5D_%23Amaj7%0A27%2F16%0A%5B1%2F1%2C_5%2F4%2C_3%2F2%2C_27%2F16%2C_15%2F8%5D%0A%23_etc...%0A(1)_3%2F2_5%2F4_1%2F1_10%2F9_4%2F3_30%2F18_2%2F1_15%2F8--." title="Xenpaper" frameborder="0"></iframe>

After applying these cultural traditions and extrinsic expectations on top of the semitone cancellation conjecture, you can get a pretty accurate model of tonality. But doing so requires musical sensitivity to the cultural traditions of the music in question in the first place. So, you still need to shed (practice), but hopefully you will have a clearer idea of what exactly to shed: divide your shed between shedding the axioms of physiology, psychoacoustics and math, and shedding the subjective rules, conscious that these are subjective rules, and juxtaposing them against musical cultures that don't have such rules. This will make the shed process much clearer and give you a beneficial, organic, constructive view of music, rather than prescriptivist, or descriptivist.

:::success

### Assignment 1:

Apply the semitone cancellation conjecture to the other two examples: Bach Prelude in C major WTC 1, and Do-Re-Mi, or whatever other (non-atonal) music of your choice.

Whenever some 'tonic set' doesn't seem to work, consider what cultural rules are required to make certain exceptions to make implicit 'detonicizations'.

:::

-----

Section I Part 5 ("What is a chord") onwards continued in the [next installation: GMT3B](https://hackmd.io/@euwbah/GMT3B)