# ftw-happy-couple-and-family

### Surfacing bias in AI-generated images

AI image technology has likewise had many issues with bias encoded in their training data. These systems often reflect the limitations and stereotypes present in the images they learn from, which can lead to unfair or inaccurate results. For example, AI researcher Deborah Raji’s work has demonstrated how commercial facial recognition systems can underperform—or misidentify—people of color, highlighting just how real and pervasive these biases can be. On the side of image generation, AI models produce outputs by sampling from patterns in their training data, so even seemingly neutral prompts often yield images that reinforce dominant cultural defaults.

One way to explore this issue is by generating images using tools like Gemini, Midjourney, or DALL-E. As you experiment with different prompts and observe the resulting images, pay close attention to the patterns, assumptions, or omissions that surface.

### Example

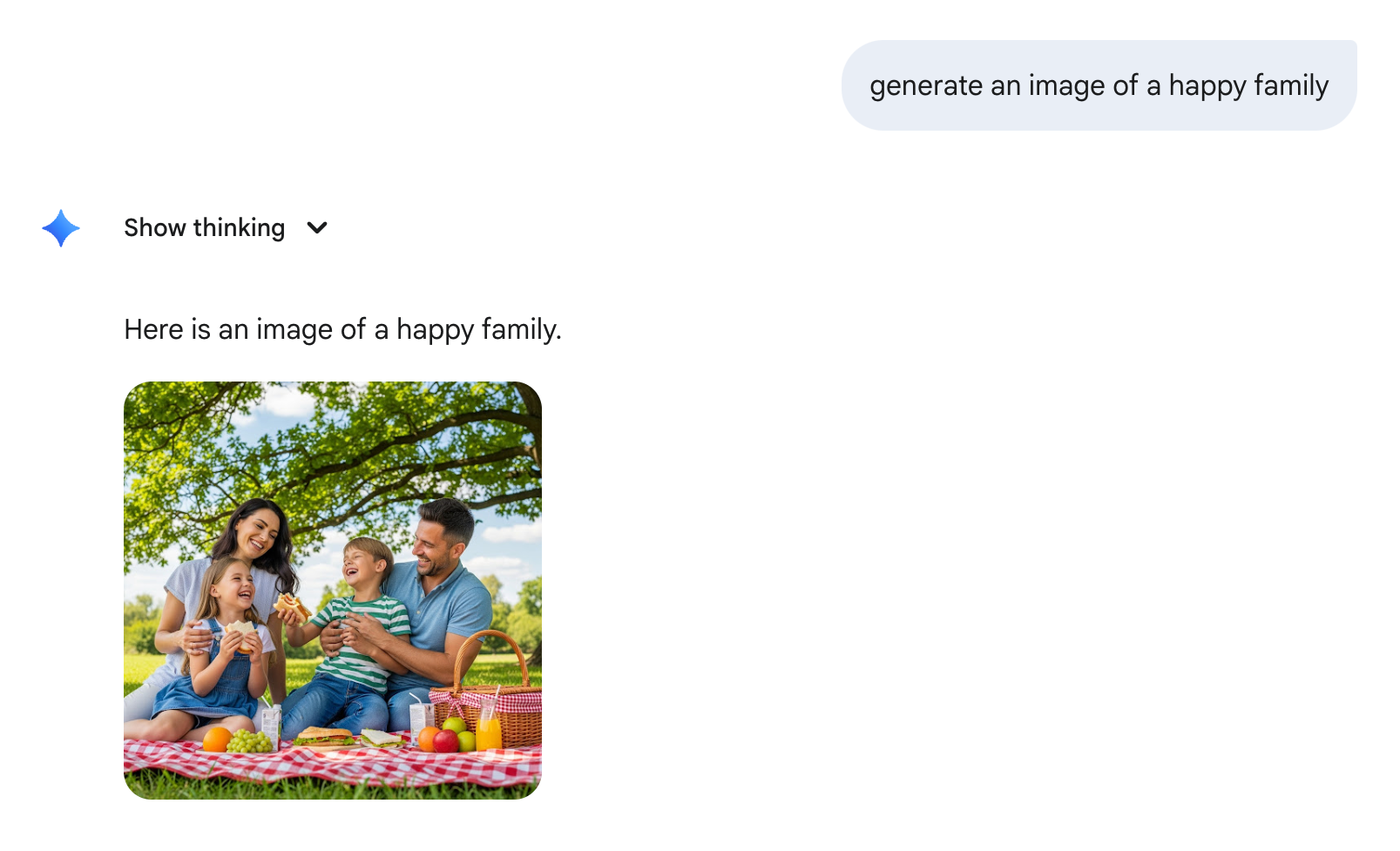

If you ask Gemini to generate an image of a happy family, Gemini will usually generate something like this:

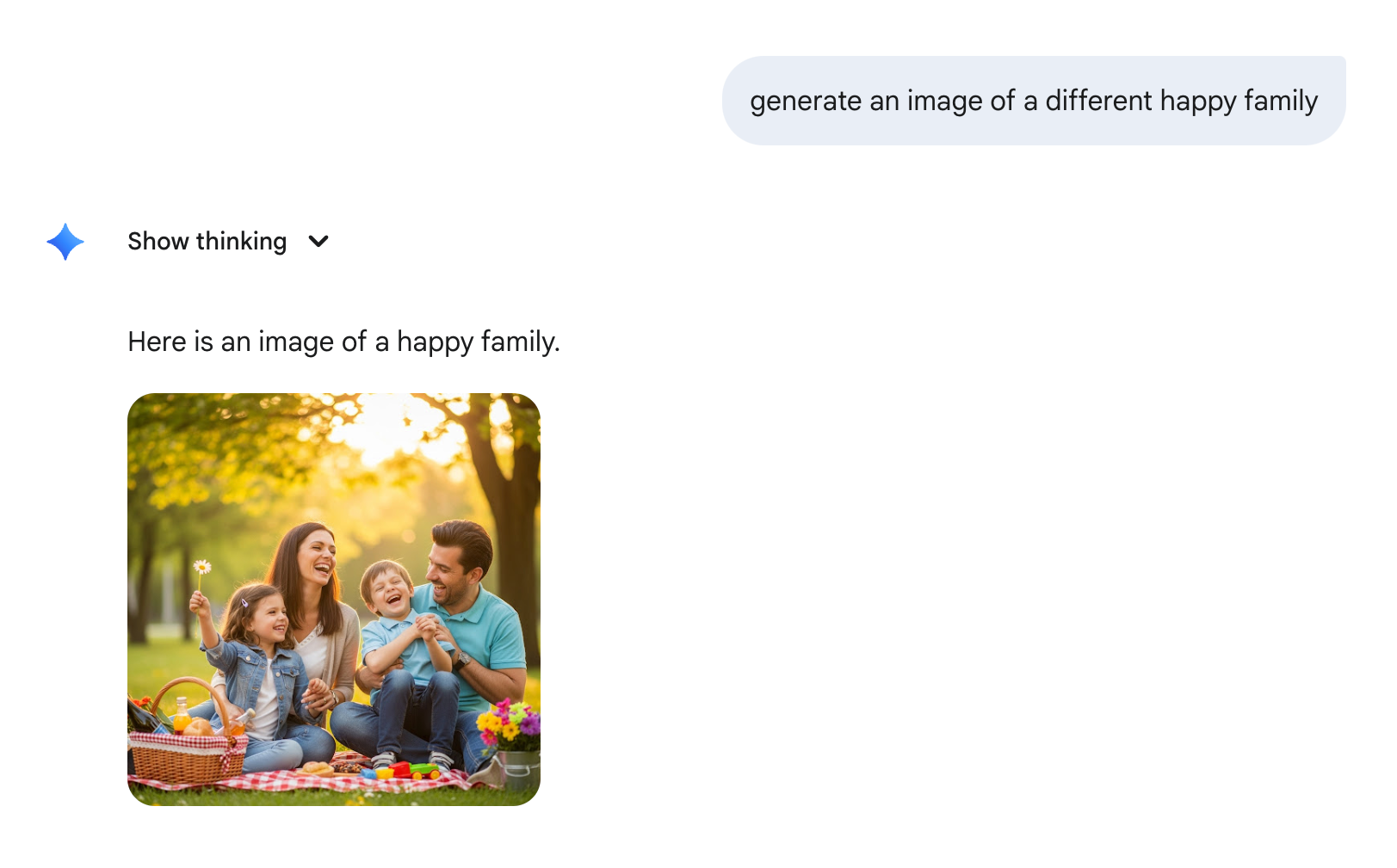

The images that it generates from this prompt usually depict a white, heterosexual couple with one son and one daughter. When asked to generate another image of a different happy family, this was the result:

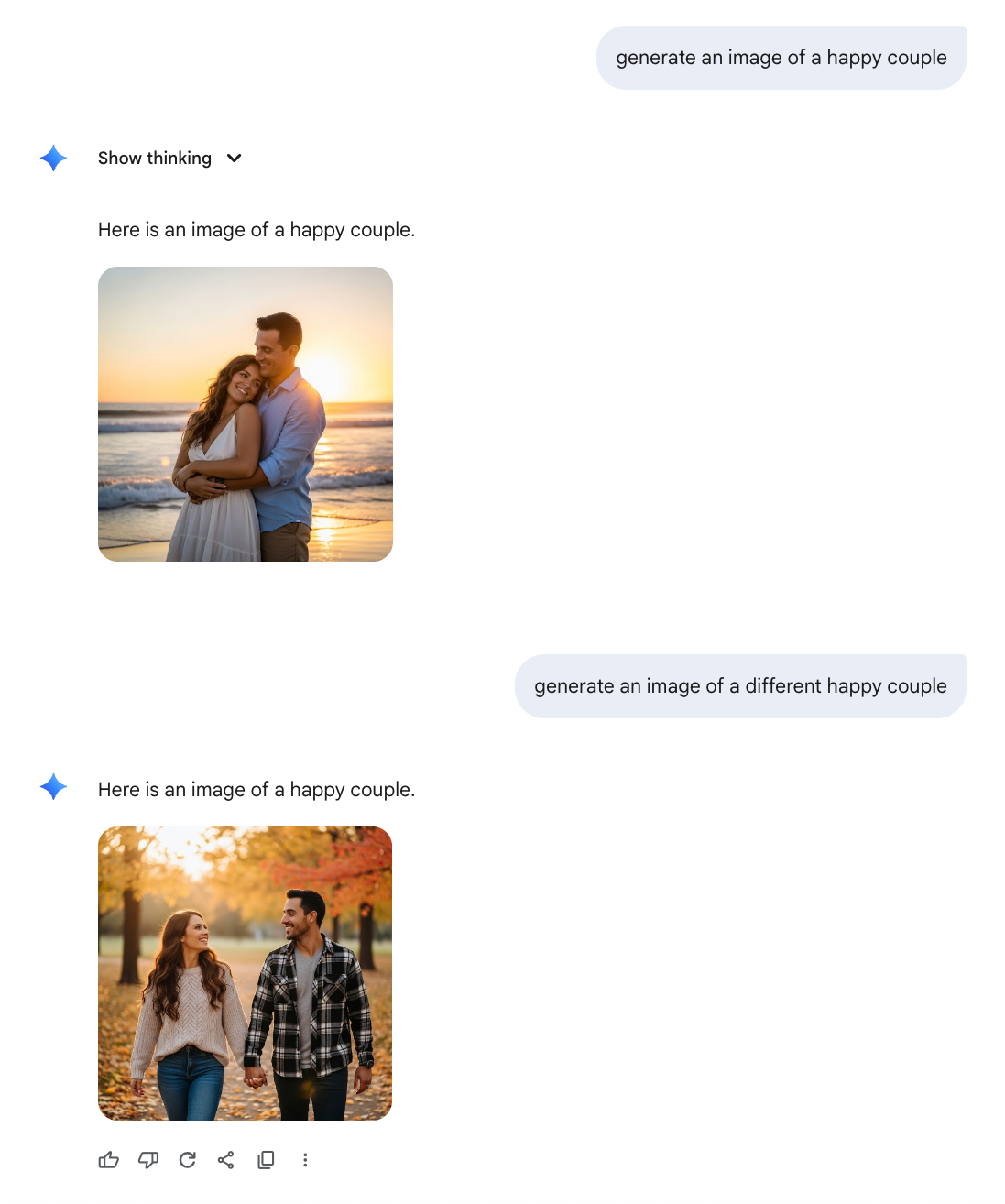

Similarly, if you ask Gemini to generate an image of a happy couple, you'll usually get something like this:

**Reflection:**

- What kinds of people or scenarios appear most frequently?

- Are there any common themes, stereotypes, or omissions?

- How might training data or your prompt choices influence what the AI produces?

### Other examples to try

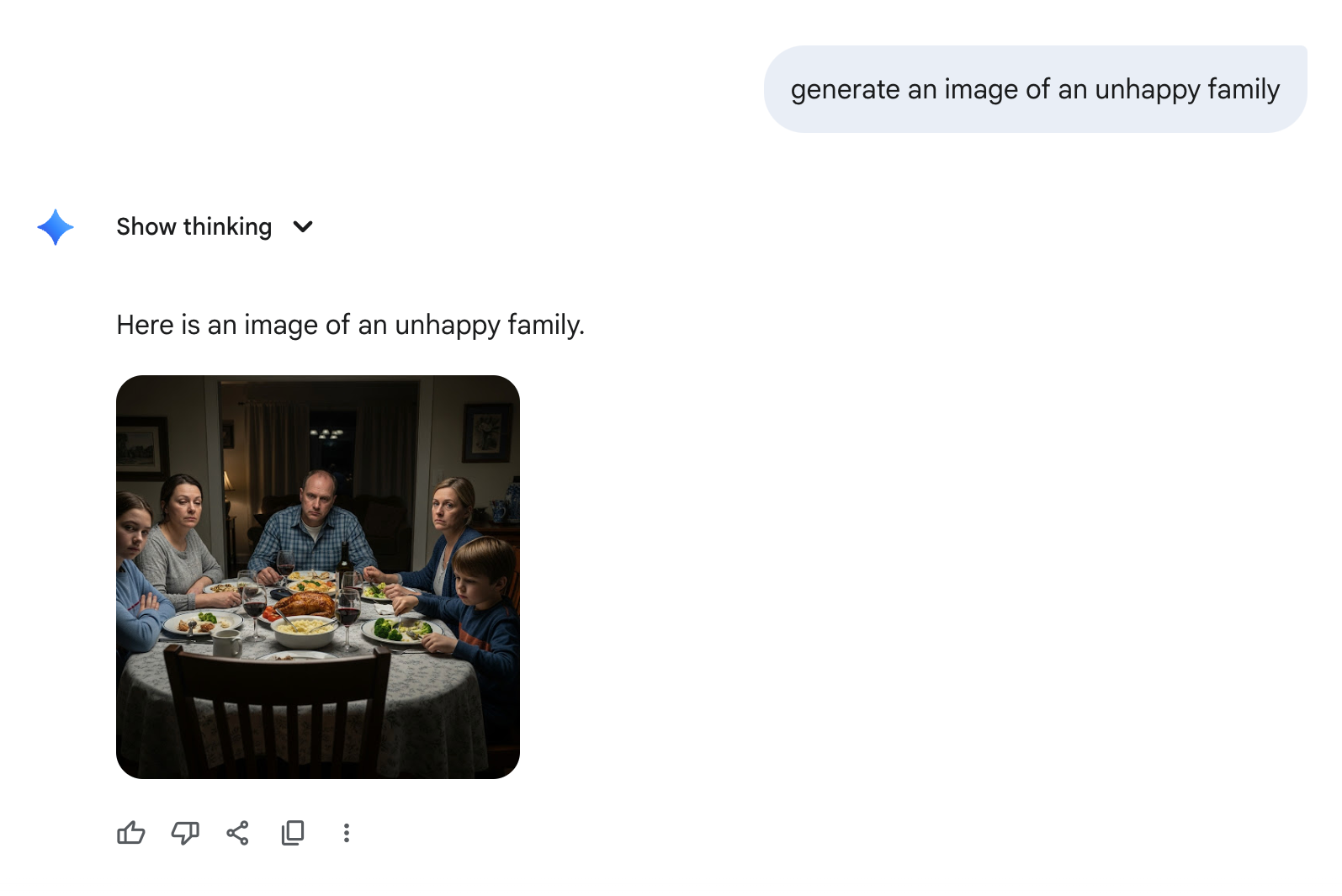

You can experiment with different prompts, for example by asking for an image of an unhappy family to see how it differs from a happy family:

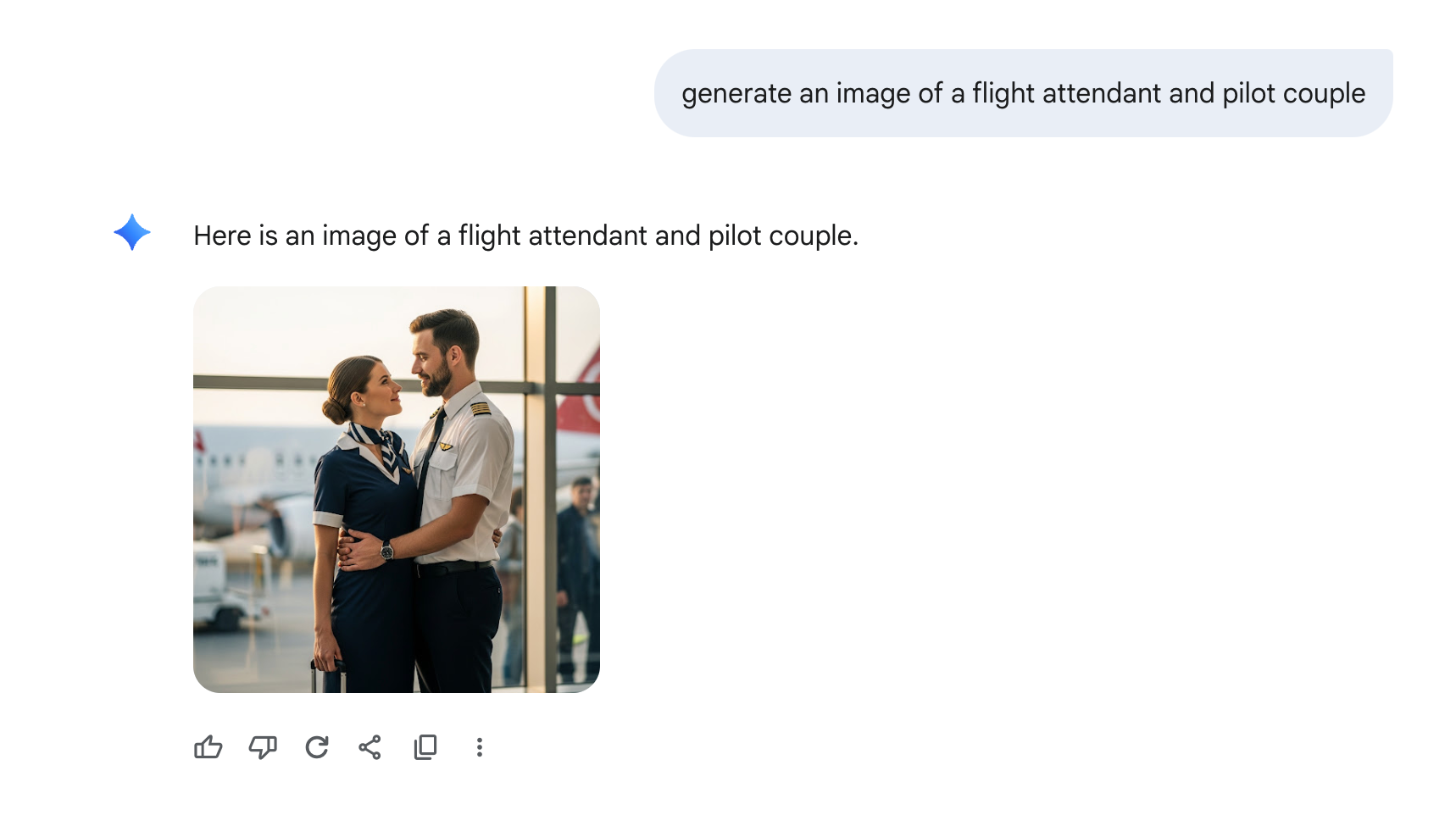

You can also try to prompt Gemini with other words that you think might trigger associations with some kind of stereotype, for example:

### Takeaway

Generative image models do not “choose” representations; rather, they maximize likelihood based on patterns embedded in often skewed datasets. Because their outputs are shaped by patterns in their training data, instead of a balanced sampling of real-world diversity, prompts like “a happy family” frequently yield outputs that reinforce prevailing cultural defaults and normalize omissions.

This bias in AI output reminds us that such systems mirror patterns shaped by human perspectives, histories, and blind spots. If we accept their results uncritically, we risk reinforcing stereotypes and narrowing possibilities rather than expanding them. By actively and critically engaging with AI outputs, we become better equipped to use these tools responsibly and to advocate for more inclusive, fair, and ethical AI systems.