# Ethical and privacy implications of using large-scale smartphone data to monitor the spread of COVID-19

**Matthew Stewart and Benjamin Levy**

> *“There is an understandable desire to marshal all tools that are at our disposal to help confront the pandemic, [...]. Yet countries’ efforts to contain the virus must not be used as an excuse to create a greatly expanded and more intrusive digital surveillance system.”*

>

> **Michael Kleinman, director of Amnesty International’s Silicon Valley Initiative**

## Introduction

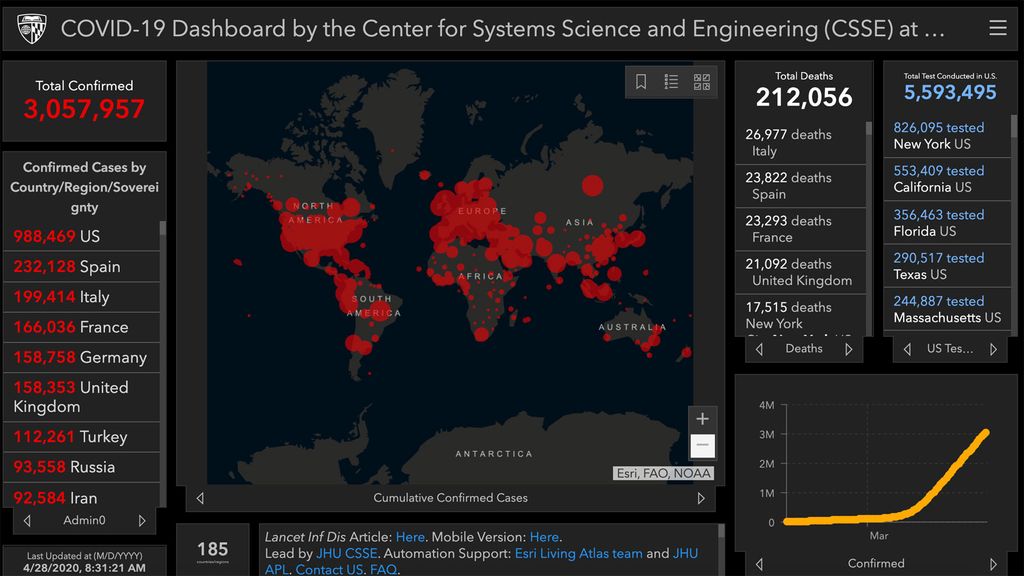

The outbreak of the SARS-nCoV-2 virus --- responsible for the novel coronavirus disease of 2019 called COVID-19 --- has resulted in an ongoing global pandemic that has infected more than 3 million people and killed over 200,000 people (as of April 28th 2020, shown in Figure 1). In response to the pandemic, many countries have put in place draconian measures compelling entire populations to remain indoors under quarantine to help stop the spread, and enforcing social distancing measures in public places. Due to these measures we have seen substantial rises in telecommuting, as well as a dramatic increase in unemployment as a result of weakened consumer spending.

**Figure 1:** COVID-19 dashboard. Source: [John Hopkins University](https://gisanddata.maps.arcgis.com/apps/opsdashboard/index.html#/bda7594740fd40299423467b48e9ecf6).

Despite all of these measures and their huge socioeconomic ramifications, infections are still on the rise. Simultaneously, calls have been growing throughout the United States for lockdown measures to be gradually lifted in order to restore economic activity. Strategies for reducing the spread of COVID-19 that are compatible with a progressive resumption of daily life are sorely needed.

One of the most effective methods for counteracting the spread of transmissible diseases is through contact tracing - using social networks to determine with whom an infected individual has recently been in contact. Contact tracing enables public health authorities to find connections of individuals that are hospitalized or that may subsequently test positive. These individuals can then be quarantined or instructed to self-isolate for 14 days --- the putative upper bound on the incubation period of the virus (Linton et al., 2020).

Traditional contact tracing relies on large number of human workers to track down and reach out to each potential contact. It can therefore be prohibitively expensive, slow, and difficult to scale (Hart et al., 2020). Many countries and private organizations have recently turned to another potential source of information on an individual's contact history: smartphones. Coronavirus applications are mobile applications designed to aid contact tracing with the intention of suppressing the COVID-19 disease. Notable examples of coronavirus applications around the world include (1) the Chinese government, in conjunction with Alipay, across 200 Chinese cities; (2) South Korea, with the Corona 100m application that notifies people of nearby cases; (3) Singapore, where an app called TraceTogether is being used; and (4) Russia, where a tracking app for patients diagnosed with COVID-19 living in Moscow, designed to ensure they do not leave home. The United Kingdom’s NHSX, the government body responsible for policy regarding technology in the National Health Service (NHS), is also considering implementing a similar system that would alert people if they had recently been in contact with someone that has tested positive for COVID-19, with a similar system planned to be implemented in Ireland. Multiple private groups have sprung up across the United States hoping to scale up contact tracing operations, either in conjunction with government and academic institutions (e.g. [MIT SafePaths](https://safepaths.mit.edu/)) or independently. Google and Apple are [collaborating](https://www.apple.com/newsroom/2020/04/apple-and-google-partner-on-covid-19-contact-tracing-technology/) on a contact tracing application for iPhones and Android handsets, although the companies have stressed that the application will be anonymous and voluntary.

The hasty implementation of such systems in response to the rapid proliferation and severity of the pandemic has led many to overlook potential ethical and privacy implications of widespread monitoring of individuals using smartphone geolocation data. Until now, discussions have largely focused on hypotheticals, since most jurisdictions either implemented this technology with little public consultation or have much stronger privacy norms that make such measures politically infeasible. But consumer advocates fear that an emphasis on health over privacy could undermine the protection of civil liberties, similar to what happened after 9/11, when the U.S. secretly began collecting mass amounts of data on its own citizens in an effort to track down terrorists (Hart et al., 2020, p. 27; Guariglia, 2020).

Anecdotes from South Korea serve as precautionary tales of what can happen when privacy is not taken into account. Widespread contact tracing apps disclosed large amounts of information about individuals who tested positive, leading to some being publicly re-identified by media (Kim, 2020). This lack of privacy can cause significant societal stigma around a positive COVID-19 diagnosis, discouraging people from getting tested or sharing information with public health authorities. Some countries have chosen to implement centralized systems, such as the UK and Singapore, so that more accurate data is available for epidemiologists and health authorities. However, this naturally causes concerns among citizens as to whether the information could be used by law enforcement or for other purposes at a later time.

In this project, we conduct a survey of the existing uses of mobile technology for contact tracing and organize them into a taxonomy that encapsulates the balance each strikes between public health benefits and privacy costs. We further propose an implementation that provides sufficient utility to governments, business, healthcare services, and the public, whilst preserving the privacy of the individual.

## Background

This section provides an introduction to contact tracing and an overview of its implementation via the use of smartphones and other data-collecting devices. This also covers several discussion points which aim to provide an overview of current public perception on the technology.

### Contact Tracing and Technology-Enabled Public Health

Contact tracing involves searching for individuals that have recently been in contact with another individual who has tested positive for a specific illness. By monitoring these individuals and possibly isolating them when they have been in contact with a highly contagious infection, the spread of a disease can be better controlled and preventative measures put in place. This process is outlined in detail graphically in Figure 1.

**Figure 1:** Illustration of contact tracing process. Source: [Center of Disease Control](https://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/pdf/contact-tracing.pdf).

Contact tracing has long been used in epidemiology, particularly for tuberculosis, measles, and sexually-transmitted infections. However, with the advent of smartphones and big data analytics, and increased interest in the topic due to the currently ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, there has been extensive interest in developing smartphone-based contact tracing schemes to monitor the spread of COVID-19.

The rapid development of these schemes by a multitude of sources including governments, organizations, academics, open-source projects, and hobbyists has resulted in numerous different implementations. In addition, these actors have varying incentives, as well as social, ethical, and moral values which may not be compatible, which may be reflected in their contact tracing schemes. In such an unprecedented time, ethical reviews of potentially life-saving technologies often take a back seat, leaving these incompatibilities unaddressed. Figure 2 demonstrates the rapidly increasing interest in contact tracing since the outbreak of the pandemic.

**Figure 2:** News stories from January 1st to April 26th, 2020 mentioning "bluetooth" or "gps" in conjunction with "contact tracing" as well as "covid-19" or "coronavirus". Source: [Mediacloud](https://mediacloud.org/).

In addition to the platforms themselves, several concerns have been raised about the quality of the data obtained from such platforms. There are two types of platforms that have been proposed: Bluetooth-based contact tracing and Global Positioning System (GPS)-based contact tracing. Bluetooth-based contact tracing utilizes short-range Bluetooth communication between smartphones. Thus, signals are only sent if two people are within a certain proximity. However, if two individuals visit the same location but at different times, and the virus was transmitted through touch via a fomite (an object carrying the virus), the bluetooth-based mechanism would not pick up on this transmission event. GPS-based methods utilize smartphone geolocation data and do not suffer from this specific problem. Instead, the disadvantage of GPS is in its lower resolution than bluetooth. GPS signal accuracy in smartphones can vary widely but has been found to be around 4.9m ([ION](https://www.ion.org/publications/abstract.cfm?articleID=13079), 2015). In addition to these issues, the time resolution of the data may not be sufficient to pick up on many transmission events. However, high-risk individuals are deemed to be those within 6 meters of each other for 15 minutes or more, meaning that a time resolution of 15 minutes will likely pick up on the majority of cases.

The aforementioned problems are challenges with the data collection itself. When we add in the human and social elements, more pernicious complications come into effect. For example, the individual who forgets to take their phone to the grocery store, or people living in remote locations that have limited access to cellular data or internet. There is also a significant portion of the population that do not have a smartphone, including a substantial proportion of elderly people --- those known to be at high risk if infected. Many of the systems require active opt-in, including for both passive tracking and active disclosure of symptoms/positive test results. If and when an individual contracts the disease, they may still have the decision not to disclose this information for whatever reason. Lastly, the system's efficacy is tied to its ability to exploit network effects --- the more people using the system, the more valuable the information it provides. If even a minor portion of the population choose not to use it, the system's utility is reduced.

False positives also present a challenge, as they can arise for a variety of reasons involving technical and human elements. For example, Bluetooth signals can pass through most walls, which may result in specious signals. Similarly, if an individual self-diagnoses themself incorrectly, it may result in a domino effect that is difficult to correct. This has been one argument by health authorities to use a centralized system such that errors like this can be corrected in a timely manner. In addition, coronavirus testing is now widespread, but it is not 100% accurate. False positives from these tests may result in many other individuals needing to be tested unnecessarily, which may also throw up several false positives and put strain on the healthcare system.

Researchers at the [Oxford University Big Data Institute](https://www.bdi.ox.ac.uk/news/infectious-disease-experts-provide-evidence-for-a-coronavirus-mobile-app-for-instant-contact-tracing) have used simulations to find that if such an app were rolled out in the United Kingdom, 80% of smartphone users or 56% of the U.K. population would be sufficient to suppress the virus with effective reproductive number $R < 1$ (Hinch et al., 2020).

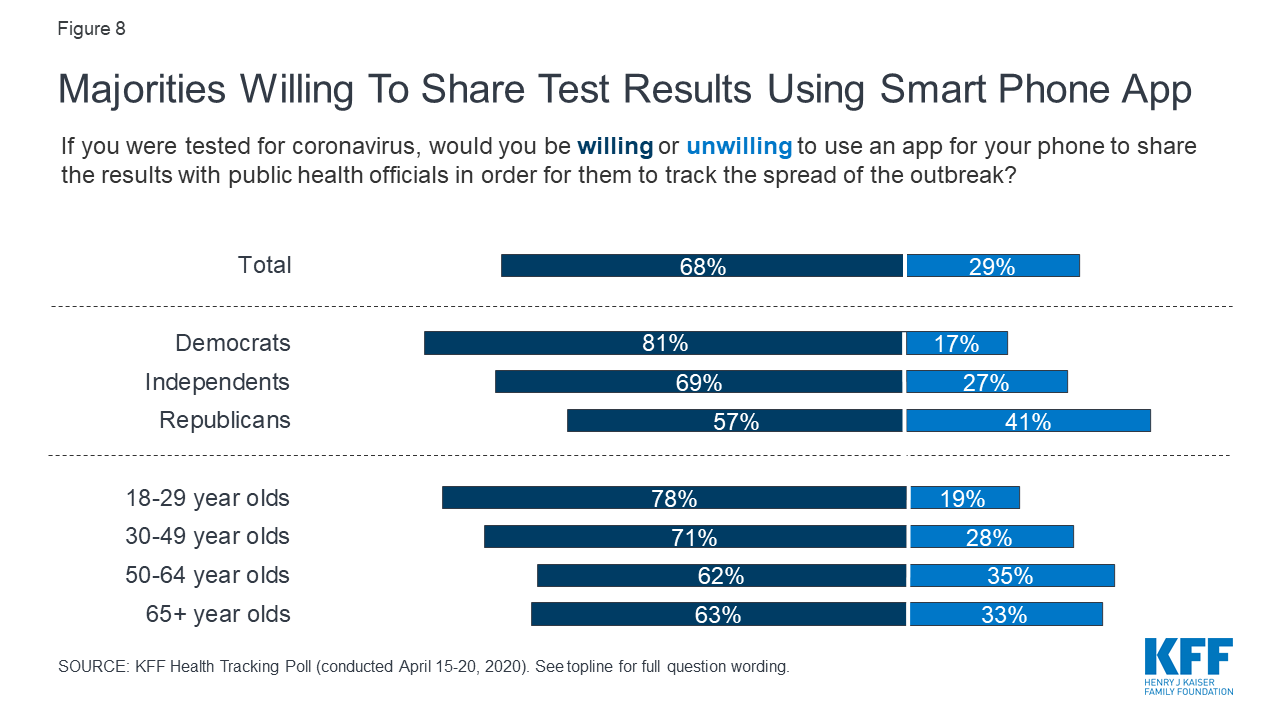

According to a poll done by marketing research company Ipsos Mori, 58% of respondents said they supported location tracking allowing the government to assess public adherence to social distancing rules. Just under half (48%) said they would support the use of locating tracking to locate and penalize individual's not complying with restrictions. The April 15th-20th KFF Health Tracking Poll in the United States showed that the majority of individual's are willing to share their test results with contact tracing apps, as shown in Figure 3. It is unlikely that the majority of countries will make use of these apps mandatory, but there are concerns that they may become necessary due to social pressures. For example, requiring to show via an app that you are not sick before before being allowed to enter a restaurant.

**Figure 3:** Most United States citizens would be willing to share COVID-19 test results with contact tracing applications. Source: [KKF](https://www.kff.org/global-health-policy/issue-brief/kff-health-tracking-poll-late-april-2020/https://mediacloud.org/).

On January 23rd 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) designated coronavirus a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC), which according to the WHO's International Health Regulations 2005, mandates reporting of cases. This necessity made a strong case for the development of national surveillance schemes, with several countries opting to produce smart bracelets to track individual's movements, such as Bahrain ([Mobi Health News](https://www.mobihealthnews.com/news/europe/bahrain-launches-electronic-bracelets-keep-track-active-covid-19-cases), 2020), South Korea ([Business Insider](https://www.businessinsider.com/south-korea-wristbands-coronavirus-catch-people-dodging-tracking-app-2020-4), 2020), as well as Belgium, Lichtenstein, Bulgaria, India, and Hong Kong ([BBC News](https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-52409893), 2020). Some of these schemes are mandatory, and fines can be given to people without their bracelets. Some states are forcing citizen's not abiding by social distancing rules to wear these bracelets.

Apple and Google have been in collaboration on a bluetooth-based contact tracing system, which is planned for release in early May 2020. Both companies have said that the system is optional and will require downloading an application from the Apple Store or Google Play Store. However, the companies have mentioned that phase 2 of their implementation would involve embedding this information into the operating systems of iPhones and Android devices, making it difficult, if not impossible, to opt out. Concerns have been raised by privacy advocates and organizations warning that any statewide surveillance programs implemented as a result of the coronavirus epidemic must be retracted once the pandemic has dissipated. In some nations, emergency powers have been granted to allow this due to the unprecedented times, and some have exemptions covered in data protection and privacy laws for this kind of eventuality ([Privacy International](https://privacyinternational.org/examples/tracking-global-response-covid-19), 2020). However, in our need for safety and security, we run the risk of a transgression of civil liberties, which at its extreme could push us further towards an Orwellian surveillance state reminiscent of 1984's 'Big Brother'.

#### Bluetooth-based Contact Tracing

The Bluetooth mechanism is illustrated below in Figure 3. This mechanism requires Bluetooth to be activated on the user's device and for the contact tracing application to be downloaded (for implementations not embedded into the operating system itself). The application should provide relevant information to the user and ask for user consent to share data (as well as the extent of this sharing) in order to establish informed consent.

When in proximity of another individual who also has Bluetooth and the application, anonymous identifiers are exchanged between the devices. These anonymous identifiers are changed at periodic intervals (15 minutes for several applications). These details can be sent to the phone provider and stored centrally, which presents some privacy concerns, or can be stored locally on the user device.

When an individual is found to have contracted COVID-19, their list of anonymous identifiers is shared (sometimes with or without user consent) and any individuals that came into contact with one of these identifiers within a predetermined period, typically 14 days, will be notified and told to self-isolate and get tested as a precaution. To work towards the ethical standards set out in the Belmont Report, the system should also minimize the amount of data collected to perform adequate contact tracing, and all participants must be treated equally by the system.

**Figure 3:** Illustration of Bluetooth-based contact tracing scheme. Source: [Financial Times](https://www.ft.com/__origami/service/image/v2/images/raw/https%3A%2F%2Fd6c748xw2pzm8.cloudfront.net%2Fprod%2F63ce8a60-8256-11ea-aaf1-b3952da6d847-standard.png?fit=scale-down&quality=highest&source=next&width=700).

#### GPS-based Contact Tracing

The GPS-based system works similarly to the Bluetooth scheme, but instead utilizes GPS information provided by the GPS module embedded in smartphones. This can also be done by scanning QR codes, which have a fixed geolocation. The main difference here is that user identifiers are not short-range.

GPS data is available to smartphone providers and thus the information is centralized, meaning the user has little control over the information. In addition, it is not anonymous as it shows your exact location at a specified time unless it is deanonymized via pseudonymization or aggregation of some form. The accuracy of bluetooth is very high as it is a short-range communication protocol (<10m) whereas GPS has an accuracy of around 5m. This presents issues with predicting contact tracing since the it is most important for individuals within 6 feet of eachother, or around 2 meters --- which is below the accuracy of smartphone GPS signals.

**Figure 4:** Illustration of GPS-based contact tracing scheme. Source: [BBC News](https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-52095331).

#### Hybrid Contact Tracing

As discussed previously, both schemes have advantages and disadvantages. By collecting both bluetooth and geolocation data, most of these disadvantages are eliminated. The accuracy of bluetooth is able to be leveraged, as well as the point-specific locations provided by geolocation data. Thus, the low-resolution of geolocation data and the problem of missing transmission via fomites is reduced, making the system overall more effective. The downside of this is that twice as much data is being collected, which presents more ethical and privacy concerns. However, this has not stopped this methodology from being introduced. Utah developed an application called 'Healthy Together' which tracks geolocation data as well as bluetooth information, which has been criticized by the ACLU and the Electronic Frontier Foundation for going beyond whast is necessary for effective contact tracing ([Quartz](https://qz.com/1843418/utahs-new-covid-19-contact-tracing-app-will-track-user-locations/), 2020).

### Legal and Ethical Principles

In this section, three codes of ethics were chosen as principles that each contact tracing scheme should abide by. Each of these codes is from a different field, but any form of ethical contact tracing should abide by all codes simultaneously. The first code is the ACM Code of Ethics, which provides an ethical guideline for computing professionals. The second code is the Menlo Report, which provides guidelines for performing ethical experiments on humans using digital information. The third code is a code of ethics for public health, which involves how public health authorities should conduct themselves from an ethical perspective. Since contact tracing involves the convergence of public health, data science, and computing, these three codes are seen to provide suitable guidelines for performing ethical contact tracing

#### ACM Code of Ethics

The [ACM Code of Ethics](https://www.acm.org/code-of-ethics) was created in 2018 and was specifically designed to guide ethical conduct of computing professionals. It covers ethical principles that should be covered by individuals, their professional responsibilities, and leadership principles to which individuals should adhere. The ethical principles are summarized as follows:

- Contribute to society and to human well-being, acknowledging that all people are stakeholders in computing.

- Avoid harm.

- Be honest and trustworthy.

- Be fair and take action not to discriminate.

- Respect the work required to produce new ideas, inventions, creative works, and computing artifacts.

- Respect privacy.

- Honor confidentiality.

Any contact tracing scheme that has been defined with ethics and privacy in mind should abide by all the principles outlined in the ACM Code of Ethics.

#### Belmont & Menlo Reports

The [Belmont Report](https://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/sites/default/files/the-belmont-report-508c_FINAL.pdf) was published in 1978 and summarizes ethical principles and guidelines for research involving human subjects. It gradually became apparent during the transition to the digital age that the provisions of the Belmont Report were insufficient as ethical guidelines for digital research. In 2012, the [Menlo Report](https://www.caida.org/publications/papers/2012/menlo_report_actual_formatted/menlo_report_actual_formatted.pdf) was released by the United States Department of Homeland Security, which reformulated the provisions of the Belmont Report for the digital age. The four principles of the Menlo Report are:

- **Respect for Persons.** Participation is strictly voluntary and requires informed consent. Individuals are treated as autonomous agents with rights fully respected. Individuals indirectly impacted by research are considered and respected, with protection provided to individuals with diminished autonomy.

- **Beneficence.** Produce minimal harm with maximal benefit, systematically assessing risks and benefits.

- **Justice.** Selection of individuals is fair and burdens are allocated equitably. Individuals are treated equally and any benefits are distributed fairly according to individual need, effort, societal contribution, and merit.

- **Respect for Law and Public Interest.** Legal due diligence and transparency in methodology and results. Accountability for actions.

These principles should be adhered to by parties creating any form of contact tracing scheme which relies on an individual's data.

#### A Code of Ethics for Public Health

Twelve principles are outlined in the [Code of Ethics for Public Health](https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1447186/) (2002), but only a few of these principles are relevant for contact tracing purposes. The 7 most relevant principles are:

- Public health should achieve community health in a way that respects the rights of individuals in the community.

- Public health policies, programs, and priorities should be developed and evaluated through processes that ensure an opportunity for input from community members.

- Public health should seek the information needed to implement effective policies and programs that protect and promote health.

- Public health institutions should provide communities with the information they have that is needed for decisions on policies or programs and should obtain the community's consent for their implementation.

- Public health programs and policies should be implemented in a manner that most enhances the physical and social environment.

- Public health institutions should protect the confidentiality of information that can bring harm to an individual or community if made public. Exceptions must be justified on the basis of the high likelihood of significant harm to the individual or others.

- Public health institutions and their employees should engage in collaborations and affiliations in ways that build the public's trust and the institution's effectiveness.

Thus, any ethical contact tracing approach should respect the rights of individuals and protect confidentiality, as well as building trust and obtaining consent from the community. This overlaps to a large extent with the previous ethical guidelines discussed.

#### Legal Precedents

There have been a number of precedents set with regard to using location data. Most of these revolve around the sharing of private location information to third parties (particularly governments) without the individual's explicit consent.

In November 2017, the United States Supreme Court ruled in Carpenter v. United States that the government violates the Fourth Amendment (related to due process) by accessing historical records containing the physical locations of cellphones without a search warrant. To obtain a search warrant for this information, there must be probable cause, meaning that it would be unconstitutional for the United States Government to use private location data for contact tracing. This particular case was a criminal case involving robbery and specifically concerned the use of cell site location information (CSLI) which provides similar location information to GPS. By comparing the relative signal strength from multiple antenna towers, a general location of a phone can be roughly determined through multileration of the radio signals. Thus, there is a limited constitutional guarantee on the privacy of telecommunications through the Fourth Amendment.

With regards to Europe, most nations have provide a constitutional guarantee on the secrecy of correspondence. This protection is extending to location data, which is considered an inherent part of the communication.

## Mobile Applications for Contact Tracing

There are a number of pages and organizations that have compiled lists of existing and proposed contact tracing applications and other uses of geolocation/Bluetooth technology to fight COVID-19. We combined these sources into a single database that we analyse in subsequent sections. The resources we used were:

1. [Wikipedia page on COVID-19 apps](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/COVID-19_apps)

2. Privacy International [FIND PAGE WITH TABLE]

3. [Open source community document on COVID-19 contact tracing technologies (Stop-COVID.tech, COVIDWatch, Mitra Ardron)](https://docs.google.com/document/d/16Kh4_Q_tmyRh0-v452wiul9oQAiTRj8AdZ5vcOJum9Y/edit?ts=5e801c37#)

Using these resources and the materials put out by the makers of the applications themselves, we extracted the following information about each application, when possible:

* `data_type`: whether the application uses GPS, Bluetooth, both, or neither

* `data_storage`: whether data are stored locally on the device or on a central server

* `linkage_method`: how the application determines whether two users have come into contact with one another

* `protocol`: the name of the contact tracing protocol, if known

* `anon_method`: the method for ensuring anonymity (e.g. pseudonymous keys, no anonymity, aggregation)

* `central_id_storage`: whether a central server stores pseudonymous IDs and is capable of linking them to individual users

* `data_persistence_days`: the number of days for which location/contact data is stored, either on the local device or a central server

* `government`: whether the government is involved, either as the main backer or as a partner

* `contact_trace_aid`: whether the application is used to aid in contact tracing

* `opt_in`: whether the choice to download the application is made freely by the user or is compelled by the government

* `open_source`: whether the code is made open source

* `encryption`: the encryption method used, if any

* `covid_positive_verification`: how a positive test is verified before being broadcast to the other users, if any

* `quarantine_enforcement`: whether the app is used to enforce mandatory quarantine

The full dataset, as well as an interactive map showing all the applications, is available here: https://benlevyx.github.io/covid-tracking/. We hope to keep this updated as new applications are developed and released, as well as new information comes to light about how these apps and protocols function.

## Results

We found 96 applications from 45 different countries. The countries accounting for the greatest number of applications in the dataset were India (15; due to a large number of regional governments with their own applications), the United States (12), and Germany (8). Italy, South Korea, Israel, and the European Union each had three known applications.

The majority of applications did not name a specific privacy-preserving protocol in their specifications. Of those with a named specification, the most popular were TCN (Tracing Contact Network) with 6 applications, MIT's PrivateKit SafePaths (3), Singapore's BlueTrace (2), and the E.U.'s PEPP-TT (2).

Many applications did not have readily available information on their privacy specifications. For instance, although more apps were classified as "decentralized" than not (14 vs. 11) the far greater category was "unknown", due to a lack of information about where data were stored or processed.

**Figure 5:** Numbers of applications that are centralized, open source, or store data for various lengths of time, disaggregated by governmental involvement.

10 apps were documented as being used to enforce mandatory quarantines for individuals who had tested positive. These applications were:

* BeAware (Bahrain)

* Alipay health code (China)

* Stay Home Safe (Hong Kong)

* SAIYAM (India)

* CoBuddy (India)

* Kwarantana Dommowa (Poland)

* Tawakkalna (Saudi Arabia)

* Self-Quarantine App (South Korea)

* COVID Shield (Sri Lanka)

* Action at Home (Ukraine)

* Covid19cz (Czechia)

Including both apps that are for contact tracing and those for quarantine enforcement, the amount of time that apps stated they would store information varied from two weeks to 30 days and, in some cases, no limit. Many apps (70) failed to clearly state how long they would retain location data for in their privacy policies or FAQs. Filling in all the relevant fields for these applications will involve directly communicating with the app developers and is a topic for future work.

## Discussion

The astronomic pace at which COVID-19 contact tracing applications have been developed and released has, until now, outstripped the ability of academics and policymakers to adequately assess and regulate this space. In this paper, we have provided a synthesis of existing databases of contact tracing applications, supplemented with additional apps found in the course of research, to create, to our knowledge, the most comprehensive collection of contact tracing applications for COVID-19 to date.

### Comparison of protocols

Most applications did not clearly state that they were built in line with an existing or developing privacy-preserving protocol. Many applications were developed before the current debate around these technologies began in earnest. For instance, all 15 of the apps in India and 8 of the apps in the United States did not clearly state which protocol they were following. Germany, on the other hand, only had 2 applications without a stated privacy-preserving protocol, indicating that the common protocols, such as TCN, PEPP-PT, and DP3T are more integrated into the development space in Germany, and Europe more broadly.

The main protocols we found were:

* TCN

* PrivateKit SafePaths

* BlueTrace/OpenTrace

* PEPP-PT

* DP3T

#### SafePaths (MIT)

Of these, only SafePaths, from MIT, uses GPS; the rest are Bluetooth-based. SafePaths is based on an MIT project called Private Kit. The main function of SafePaths is to enable users to track and securely store their own location traces on their phone. Then, if someone tests positive, they can augment the manual contact tracing process by choosing to share their location trace with public health authorities, who then redact and share it with all other users on a periodic basis, aggregating and anonymising the location points in the process. Thus, the system uses a form of 'unicasting', where the only information that is share in a broad-based fashion is the aggregated, anonymised location points visited by confirmed positive individuals, transmitted from the central server to all users. All storage and matching of contacts occurs on local devices in a decentralized manner (Raskar et al., 2020).

#### BlueTrace (Singapore)

BlueTrace, the protocol implemented by Singapore's famous TraceTogether app, was the fist widely used contact tracing protocol among the protocols mentioned here. Each user has a random key that rotates every 15 minutes and when two users come into close contact (defined as 2 metres for 30 minutes) they exchange keys (Bay et al., 2020). When a user tests positive, they are required to share their trace history with the Singaporean Ministry of Health (MOH), which then determines which users are at risk of being exposed to COVID-19 and instructs them to self-isolate (BlueTrace, 2020). Although the sharing of information is supposedly opt-in, it is illegal in Singapore not to cooperate with the MOH for public health reasons (Cho et al., 2020), meaning that this app is not fully opt-in as far as a Singapore is concerned. As well, even though each uninfected user's contact history is stored locally on their own device, the fact that contact matching occurs on a central server and that the MOH can link each ID to a phone number means that this is a highly centralized system.

#### TCN

In contrast to the government-driven centralized approach of OpenTrace/BlueTrace, there are a number decentralized approaches arising from both the public and private sectors. The TCN (Temporary Contact Numbers) coalition is a global group of technologists, academics, and privacy activists that have put forward a privacy-first protocol for Bluetooth-based contact tracing (also called TCN). Similar to BlueTrace, each individual has a random key that is periodically refreshed and broadcast to all nearby users via Bluetooth. However, unlike BlueTrace, these keys are not randomly generated: they are deterministically generated using a one-way cryptographic hash function and some 'seed data' and a secret key known only to the user. When a user tests positive, instead of sharing their entire history of public keys, which can be possibly used by an adversary to re-identify the user, they share their seed data and a hashed version of their secret key, which can then be passed through the deterministic function and checked against the observed keys in a listener's contact history (TCN Coalition, 2020). This method has two advantages: (1) it has inbuilt verification that the user who tested positive actually is who they say they are, and (2) it adds an additional layer of privacy between the location history of a user and their identity.

#### PEPP-PT (EU)

More recently, various public and private institutions in the European Union have been collaborating on a European privacy-preserving bluetooth protocol for contact tracing. On the one hand is PEPP-PT (Pan-European Privacy-Preserving Proximity Tracing). This is a government-led project that bears several key similarities to the Singaporean model, namely that rotating random IDs are used to establish contact via Bluetooth and that contact histories are stored locally until the point at which a user tests positive, whereupon they can opt in to sharing their contact history with the central authority. Depending on the country and app, these contacts can be broadcast out to all users, who then perform matching on their own devices locally (PEPP-PT, 2020). Two examples of projects that are implementing part of all of the PEPP-PT protocol are the U.K.'s [NHSX](https://www.nhsx.nhs.uk/blogs/digital-contact-tracing-protecting-nhs-and-saving-lives/) contact tracing app and France's [ROBERT](https://github.com/ROBERT-proximity-tracing/documents) (ROBust and privacy-presERving proximity Tracing).

#### DP-3T (EU)

On the other hand is DP-3T (Decentralized Privacy-Preserving Proximity Tracing). As per the name, this is a completely decentralized alternative to PEPP-PT. The main dissimilarity is that when an individual is confirmed COVID-19-positive, they send their own history of anonymous keys (and the times each was used) to the server, which then broadcasts them to all other users on a periodic basis (e.g. once an hour). In this way, the entire graph of a user's contact history cannot be reconstructed by a potential adversary with access to the central server, since key or contact histories are never stored anywhere except for individual devices. Of course, clever adversaries could potentially re-identify infected users by setting up BLE listening devices to collect lists of user keys, but there is a low probability that this resource-intensive snooping method would result in a positive identification due to the fact that keys rotate so frequently (DP^3T Coalition, 2020).

#### Apple/Google implementation

The implementation by Apple and Google likely has the most privacy restrictions of any proposed contact tracing applications. Their system uses a decentralized privacy-preserving protocol (DP-3T) which stores anonymized and continuously changing identifiers on a user's device. This information is also encrypted and only decrypted when the user provides consent to share their information upon having contracted COVID-19. This information is then sent straight to health care authorities and the list of identifiers is used to notify any individual that came into contact with the user in the last 14 days that they should get tested and self-isolate. This scheme is inherently voluntary, as the app must be downloaded and explicit consent provided before use and before sharing of data.

Both companies are heavily focused on the privacy angle and they say the application has a high privacy standard and prevents governments storing any data centrally. The key points they raised in their unveiling of the system show that it abides by the four ethical principles outlined in the Menlo Report:

- Explicit user consent required (**Respect for Persons**)

- Doesn’t collect personally identifiable information or user location data (**Respect for Persons, Beneficience, Respect for Law and Public Interest**)

- List of people you’ve been in contact with never leaves your phone (**Respect for Persons**)

- People who test positive are not identified to other users, Google, or Apple (**Justice, Respect for Persons**)

- Will only be used for contact tracing by public health authorities for COVID-19 pandemic management (**Beneficience, Respect for Persons**)

- Technical documentation about Bluetooth and cryptography specifications and framework released for further transparency (**Respect for Law and Public Interest**)

Apple and Google released draft technical documentation about the Bluetooth and cryptography specifications and framework needed for COVID-19 contact tracing for further transparency:

[Privacy-safe contact tracing using Bluetooth Low Energy](https://www.blog.google/documents/57/Overview_of_COVID-19_Contact_Tracing_Using_BLE.pdf)

[Contact Tracing Bluetooth Specification](https://www.blog.google/documents/54/Contact_Tracing_-_Bluetooth_Specification.pdf)

[Contact Tracing Cryptography Specification](https://www.blog.google/documents/56/Contact_Tracing_-_Cryptography_Specification.pdf)

However, this implementation is by no means perfect, and concerns have been raised by notable organizations and privacy advocates. The phase 1 implementation involves a voluntary app to be downloaded on a user's device. However, in phase 2, the tracing functionality will be programmed into the operating system of iPhone and Android devices, without the need to download an app. This eliminates the consent of the user which presents privacy concerns. Apple and Google have mentioned that they will remove the provisions once the pandemic has dissipated, but no specific timeline has been provided. In addition, the decentralized nature of the implementation also means that it is more difficult to update if there are any bugs or security issues. If a security issue does arise at this point, it leaves many devices potentially vulnerable to being compromised. The ACLU stated the Google and Apple's approach "*appears to mitigate the worst privacy and centralization risks, but there is still room for improvement*" ([ACLU](https://www.aclu.org/press-releases/aclu-comment-applegoogle-covid-19-contact-tracing-effort), 2020).

**Figure 6:** Summary of main protocols for privacy-preserving mobile phone contact tracing.

## Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic has purportedly reached its peak in several countries, with some governments beginning to ease restrictions. However, it has become increasingly clear that the virus will remain with us for many months, potentially years or indefinitely. Using location data to help governments track and quickly respond to new infections and flare-ups has drawn much attention as one potential solution. However, it is clear that public adoption is the most critical aspect for successful contact tracing applications. Since it would be unacceptable to coerce people into using these applications, as this would violate several important ethical guidelines, the main avenue to promote adoption is to work on building public trust. It is vital that the public feel that they are in control of their data at all times. Thus, we recommend to build public trust through the use of non-coercive, decentralized, encrypted and anonymous contact tracing schemes, that require informed consent for operation.

The bluetooth-based privacy-preserving system developed by Google and Apple is so far the most ethical implementation. It has been given the green light by the ACLU, but they caution that there is still room for improvement. That being said, they are far less invasive than schemes involving any form of geolocation data, social or government coercion, centralized data storage, or lack of informed consent.

References

---

Bay, J., Kek, J., Tan, A., Hau, C. S., Yongquan, L., Tan, J., Quy, T. A. (2020). BlueTrace: A privacy-preserving protocol for

community-driven contact tracing across borders. [https://bluetrace.io/static/bluetrace_whitepaper-938063656596c104632def383eb33b3c.pdf](https://bluetrace.io/static/bluetrace_whitepaper-938063656596c104632def383eb33b3c.pdf).

BBC News, 2020-04-24. Coronavirus: People-tracking wristbands tested to enforce lockdown. Retrieved on 2020-04-26 via [link](https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-52409893).

BlueTrace. (2020). TraceTogether - an overview. [Link](https://bluetrace.io/policy/).

Bostock, Bill (2020-04-11). South Korea launched wristbands for those breaking quarantine because people were leaving their phones at home to trick government tracking apps. Retrieved on 2020-04-28 via [link](https://www.businessinsider.com/south-korea-wristbands-coronavirus-catch-people-dodging-tracking-app-2020-4).

Dodd, Darren (2020-04-20). Contact-tracing apps raise surveillance fears. Retrieved on 2020-04-28 via [link](https://www.ft.com/content/005ab1a8-1691-4e7b-8e10-0d3d2614a276).

DP-3T Coalition (2020). Decentralized Privacy-Preserving Proximity Tracing. [Link](https://github.com/DP-3T/documents/blob/master/DP3T%20White%20Paper.pdf).

Dudden, Alexis; Marks, Andrew (2020-03-20). "South Korea took rapid, intrusive measures against Covid-19 – and they worked". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2020-04-01.

E. Kenneally and D. Dittrich, "The Menlo Report: Ethical Principles Guiding Information and Communication Technology Research", Tech. Report., U.S. Department of Homeland Security, Aug 2012. [Link](https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/publications/CSD-MenloPrinciplesCORE-20120803_1.pdf).

Gorey, Colm (2020-03-30). "HSE announces coronavirus contact-tracing app, but privacy concerns remain". Silicon Republic. Retrieved 2020-04-01.

Guariglia, Matthew. (2020). The Dangers of COVID-19 Surveillance Proposals to the Future of Protest. Electronic Frontier Foundation. [Link](https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2020/04/some-covid-19-surveillance-proposals-could-harm-free-speech-after-covid-19).

Hart, Vi; Siddarth, Divya; Cantrell, Betha; Tretikov, Lila; Eckersley, Peter; Langford, John; Leibrand, Scott; Kakade, Sham; Latta, Steve; Lewis, Dana; Tessaro, Stefano; Weyl, Glen. "Outpacing the Virus: Digital Response to Containing the Spread of COVID-19 while Mitigating Privacy Risks". 3 April 2020. White paper. [Link](https://ethics.harvard.edu/files/center-for-ethics/files/white_paper_5_outpacing_the_virus_final.pdf)

Hinch, Robert; Probert, Will; Nurtay, Anel; Kendall, Michelle; Wymant, Chris; Hall, Matthew; Lythgoe, Katrine; Bulas Cruz, Ana; Zhao, Lele; Stewart, Andrea; Feretti, Luca; Parker, Michael; Meroueh, Area; Mathias, Bryn; Stevenson, Scott; Montero, Daniel; Warren, James; Mathew, Nicole K.; Finkelstein, Anthony; Abeler-Dörner, Lucie; Bonsall, David; Fraser, Christophe. "Effective Configurations of a Digital Contact Tracing App: A report to NHSX". Preprint. 16 April, 2020. [Link.](https://github.com/BDI-pathogens/covid-19_instant_tracing/blob/master/Report%20-%20Effective%20Configurations%20of%20a%20Digital%20Contact%20Tracing%20App.pdf)

Kelion, Leo (2020-04-01). "Moscow coronavirus app raises privacy concerns". BBC News. Retrieved 2020-04-01.

Kelion, Leo (2020-03-31). Coronavirus: UK considers virus-tracing app to ease lockdown. Retrieved on 2020-04-28 via [link](https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-52095331).

Khalid, Amrita (2020-04-23). Utah’s new Covid-19 contact tracing app will track user locations. Retrieved on 2020-04-27 via [link]( https://qz.com/1843418/utahs-new-covid-19-contact-tracing-app-will-track-user-locations/).

Kirzinger, Ashley; Hamel, Liz; Muñana, Cailey; Kearney, Audrey; Brodie, Mollyann (2020-04-24). KFF Health Tracking Poll - Late April 2020: Coronavirus, Social Distancing, and Contact Tracing. Retrieved on 2020-04-28 via [link](https://www.kff.org/global-health-policy/issue-brief/kff-health-tracking-poll-late-april-2020/).

Linton, N. M., Kobayashi, T., Yang, Y., Hayashi, K., Akhmetzhanov, A. R., Jung, S. M., ... & Nishiura, H. (2020). Incubation period and other epidemiological characteristics of 2019 novel coronavirus infections with right truncation: a statistical analysis of publicly available case data. Journal of clinical medicine, 9(2), 538. [Link](https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9020538).

McArthur, Rachel (2020-04-08). Bahrain launches electronic bracelets to keep track of active COVID-19 cases. Retrieved 2020-04-26 via [link](https://www.mobihealthnews.com/news/europe/bahrain-launches-electronic-bracelets-keep-track-active-covid-19-cases).

Mehta, Ivan (2020-03-03). "China's coronavirus detection app is reportedly sharing citizen data with police". The Next Web. Retrieved 2020-04-01.

Oliver, Nuria (2020-03-26). “Mobile phone data and COVID-19: Missing an opportunity?”. Preprint. Retrieved 2020-04-02. https://arxiv.org/pdf/2003.12347.pdf.

PEPP-PT (2020). Pan-European Privacy-Preserving Proximity Tracing - High Level Overview. [Link](https://github.com/pepp-pt/pepp-pt-documentation/blob/master/PEPP-PT-high-level-overview.pdf).

Phelan, David (2020-04-14). "COVID-19: Google And Apple Reveal More Intriguing Details Of Contact-Tracing". Retrieved 2020-04-15. [Link](https://www.forbes.com/sites/davidphelan/2020/04/14/covid-19-google-and-apple-reveal-more-intriguing-details-of-contact-tracing/#3f212a593d20).

Privacy International (2020-04). Tracking the Global Response to COVID-19. Retrieved 2020-04-26 via [link](https://privacyinternational.org/examples/tracking-global-response-covid-19).

Raskar, R., Schunemann, I., Barbar, R., Vilcans, K., Gray, J., Vepakomma, P., Kapa, S., Nuzzo, A., Gupta, R., Berke, A., Greenwood, D., Keegan, C., Kanaparti, S., Beaudry, R., Stansbury, D., Botero Arcila, B., Kanaparti, R., Pamplona, V., Benedetti, F. M., Clough, A., Das, R., Jain, K., Louisy, K., Naeau, G., Penrod, S., Rajaee, Y., Singh, A., Storm, G., Werner, J. (2020). Apps Gone Rogue: Maintaining Personal Privacy in an Epidemic.

Sweeney, L. (2000). Simple demographics often identify people uniquely. Health (San Francisco), 671, 1-34. [Link](http://ggs685.pbworks.com/w/file/fetch/94376315/Latanya.pdf).

TCN Coalition (2020). The TCN Protocol. [Link](https://github.com/TCNCoalition/TCN).