---

tags: ironhack, lecture,

---

<style>

.markdown-body img[src$=".png"] {background-color:transparent;}

.alert-info.lecture,

.alert-success.lecture,

.alert-warning.lecture,

.alert-danger.lecture {

box-shadow:0 0 0 .5em rgba(64, 96, 85, 0.4); margin-top:20px;margin-bottom:20px;

position:relative;

ddisplay:none;

}

.alert-info.lecture:before,

.alert-success.lecture:before,

.alert-warning.lecture:before,

.alert-danger.lecture:before {

content:"👨🏫\A"; white-space:pre-line;

display:block;margin-bottom:.5em;

/*position:absolute; right:0; top:0;

margin:3px;margin-right:7px;*/

}

b {

--color:yellow;

font-weight:500;

background:var(--color); box-shadow:0 0 0 .35em var(--color),0 0 0 .35em;

}

.skip {

opacity:.4;

}

</style>

# Node | The Internet & HTTP Server

## Learning Goals

After this lesson you will be able to:

- Understand more about what the Internet really is

- Understand the basics of client-server architecture

- Understand the basics of the request-response cycle

- Understand the concept behind HTTP

- Understand what DNS is

- Create your first backend program using Node's `http` package

## Introduction

:::info lecture

Nous allons avoir le besoin de **mettre en ligne nos pages** afin qu'elles soient accessible depuis l'extérieur, et non plus seulement sur notre machine locale.

Pour cela, nous allons faire appel à une machine dédiée, restant allumée 24h/7, connectée à internet : un serveur.

:::

:::info lecture

Rien ne nous empêcherait d'utiliser notre propre ordinateur, mais il faudrait qu'il reste allumé 24/24...

:::

Up until now, our HTML, CSS, and JavaScript code have been in static files on our computer. This works fine for local development, but what if we want the world to see our code? We need to put our static files on a **server** to make them accessible to the whole Internet.

In this lesson, we will talk about the role of **servers** in Web applications, how **HTTP** is involved and we'll even write our first (messy) server code using some of these concepts.

:::info

Even if it was easy to for people on the Internet to connect to your computer and access your Website files, your computer would need to be **turned on**, **awake** and have **Internet literally all the time**. Not very practical for our personal computers.

**Servers**, however, are exactly that: computers that are always turned on, awake and connected to the Internet so that users can connect to them.

:::

## The Internet

:::info lecture

Internet est un réseau géant de serveurs interconnectés.

:::

To talk about **servers** we really have to talk about **the Internet**. What is it, anyway? It's actually **millions of devices** connected together in a **massive network**. Some devices are connected wirelessly and others are connected with real cables.

:::info

These devices are all over the world. To connect landmasses, there are **connecting cables at the bottom of the ocean**.

Visit the [Submarine Cable Map Website](https://www.submarinecablemap.com/) to see the cables under the ocean that connect the world together.

:::

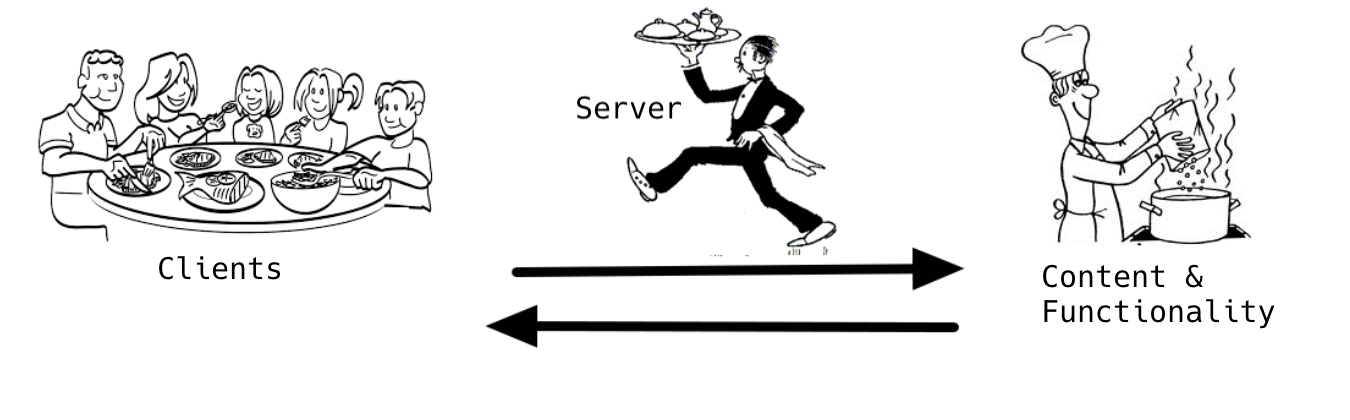

### Client-Server Architecture

:::info lecture

Pour naviguer sur internet, nous utilisons un navigateur : c'est le client.

:::

:::info lecture

Le serveur dispose du contenu tandis que le client demande et consomme le contenu.

:::

All the devices connected to the Internet are either **servers** or **clients**.

- A **server** is a device that <b>has **content</b> & functionality available for use**. Think of the server where we upload our Website code.

- A **client** is a device that wants to **<b>access the content</b> & functionality** from a _server_. Think of our own devices that we use to visit different Websites.

:::info lecture

On peut faire l'analogie avec un restaurant :

1.

2.

3.

4.

:::

Imagine that the Internet is a massive restaurant that has many different kitchens with all kinds of cuisine. In that restaurant, people wanting to eat are **clients** (they want to access the food). The waiters are the **servers** (they make the food available to the clients).

**Clients** have to ask the servers for what they want. Whatever food or drinks need to be **requested** from the server.

**Servers** have to wait on and listen to clients, figure out what they want and go to the kitchen to get it. If everything goes according to plan, the servers will get everything and they **respond** to the clients with what was asked for. If things go wrong, the server's **response** needs to communicate that to the client (like if they are out of the lasagna special).

:::warning

It may be confusing at first, but the terms **client** and **server** can each refer to two different things:

- the **physical computers (or devices)** that are connected to the Internet

- the **software** that runs on those computers.

For example, our **personal computers** can be considered **clients**, but a **Web browser application** like Google Chrome can also be called a **client**. It has a code that allows you to download content from servers like Websites, images, video, etc.

:::

### The Request-Response Cycle

:::info lecture

On parle d'architecture client/serveur où s'échangent des requêtes/réponses :

:::

The terms **request** and **response** are important ones when it comes to application development. Basically, all applications that we use are **client applications** that have code to make your computer **communicate with servers**. There are only very few exceptions (like your calculator app, probably). The way that communication happens is that your application (the client) makes a **request** for something and then a server on the Internet delivers a **response**.

This **requesting** and **responding** happens many many times while we use applications, so we call this the [request-response cycle](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Request%E2%80%93response). It's one of the most fundamental ways computers communicate with each other: the first computer (client) sends a request for some data and the second computer (server) responds to the request.

:::info lecture

Un cycle request/response type d'accès à une page web :

:::

For a Website, for example, your browser has to make all these requests (and others):

:::info lecture

Pour une page web complète, il y aura plus qu'une seule requête :

:::

1. Request the initial HTML code

2. Request the CSS file

3. Request any images (each file is a separate request)

4. Request any JavaScript files (file is a separate request)

5. Request any font files (again, each one its own request)

Here's an example of the hundreds of requests that your browser makes to visit Amazon's homepage:

:::info

You can see all the requests a Website makes by using [Chrome DevTools' Network tab](https://developers.google.com/web/tools/chrome-devtools/network-performance/reference). Open the Chrome DevTools first, select the _Network_ tab, and then visit any Website.

:::

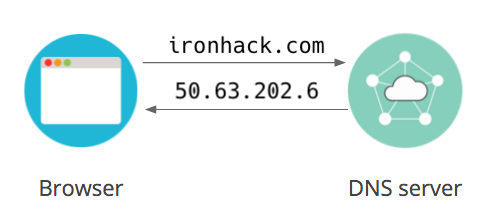

### DNS

:::info lecture

Un peu à l'instar des numéros de téléphones, chaque machine du réseau internet dispose d'une adresse unique :

:::

Every computer connected to the Internet has an **IP address**. Think of IP addresses like the street addresses of real buildings. We can connect to any "location" on the Internet because of these addresses.

An IP address consists of four numbers between 0 and 255 separated by dots. For example, this is one of Google's IP addresses: `66.102.1.102`. If you knew the IP address of your favorite Websites, you could actually paste that into your browser's location bar and it would work. The problem is that the average Internet user visits dozens of different Websites every day. Just like with real addresses, **it's difficult to remember IP addresses**. That is where DNS comes in!

:::info lecture

Plutôt que de retenir chaque numéro, un système appelé DNS va nous permettre d'associer un nom de domaine à l'IP d'une machine :

:::

The **Domain Name System**, or **DNS** for short, is what allows us to use domain names like _google.com_ instead of IP addresses. It's basically a system of online directories that can translate those domain names into the IP addresses that they belong to. Our software uses DNS behind the scenes whenever we navigate the Web.

### Elements of a URL

:::info lecture

Chaque ressource est identifiée par une "adresse" unique, c'est l'URL :

:::

```

http://www.example.org/hello/world/foo.html?foo=bar&baz=bat#footer

\___/ \_____________/ \__________________/ \_____________/ \____/

protocol host/domain name path querystring hash/fragment

```

:::info lecture

Voici l'anatomie d'une URL :

:::

Element | About

------|--------

protocol | the most popular application protocol used on the world wide web is HTTP. Other familiar types of application protocols include FTP, SSH, HTTPS

host/domain name | the host or domain name is looked up in DNS to find the IP address of the host - the server that's providing the resource

path | web servers can organize resources into what is effectively files in directories; the path indicates to the server which files from which directory the client wants

querystring | the client can pass parameters to the server through the querystring (in a GET request method); the server can then use these to customise the response - such as values to filter a search result

hash/fragment | the URI fragment is generally used by the client to identify some portion of the content in the response; interestingly, a broken hash will not break the whole link - it isn't the case for the previous elements

### HTTP (In a nutshell)

:::info lecture

HTTP est le mode de communication des machines pour échanger ces pages : c'est un protocol de communication.

:::

When you visit a Website and go through all this process of requests and responses, the first step is always typing in the URL of that Website. That's when DNS kicks in and routes you to an IP address of a server on the Internet. You probably noticed that proper URLs of all Websites start with _http_ (even if you don't type it initially).

**HTTP** stands for the *Hypertext Transfer Protocol*. It's the network protocol used to deliver virtually all files and other data (collectively called resources) on the World Wide Web, whether they're HTML files, image files, query results, or anything else.

A **protocol** is simply a set of rules for communication, in this case for communication between client and server computers. Us humans have protocols with rules to communicate with one another as well. If we don't follow the protocol, the communication will not go smoothly.

If I greet you with a "Hello", your natural assumption is to respond in English. You respond with "Hey, how are you?".

If I greet you with "Hello", and you respond with "Hola, ¿cómo estás?" the protocol is broken. We aren't communicating with the same rules, and we may not be able to understand each other.

**HTTP** is how computers on the Internet communicate. The technical details aren't important right now, but essentially clients (including your browser) use the rules of HTTP to **send its requests** to servers and servers **respond using those rules** as well. The server and the client have a small conversation to figure out what needs to happen.

An HTTP "conversation" is (conceptually) like this:

:::info lecture

Voici un ex d’échange (une page web) entre un client et un serveur :

:::

> **Client** _calls ironhack.com_

> **Client** - Hi

> **Server** - Hi

> **Client** - Can you get me `index.html`? (_this is the request_)

> **Server** _thinks_

> **Server** - Okay! Here it is.

> **Server** _sends the `index.html` file_ (_this is the response_)

> **Server** _hangs up_

All that for just the HTML. To get an image or the CSS file there has to be a completely new conversation. In these conversations, if your browser doesn't say "Hi", none of this works. That's part of the HTTP protocol.

:::info lecture

Le client demande maintenant la ressource feuille de styles :

:::

> **Client** _calls ironhack.com_

> **Client** - Hi

> **Server** - Hi

> **Client** - Can you get me `style.css`? (_this is the request_)

> **Server** _thinks_

> **Server** - Okay! Here it is.

> **Server** _sends the `style.css` file_ (_this is the response_)

> **Server** _hangs up_

:::info

If you are interested in more of the technical details of HTTP, you can [learn more about them on MDN](https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/HTTP/Overview) and see a lot of them in the **Chrome DevTools' Network tab**.

:::

## Backend

:::info lecture

Dans le module 2, nous allons donc apprendre à coder des servers qui répondent et délivrent des ressources web.

:::

Computers don't just naturally understand the HTTP protocol, how to make requests or send responses. It's the software that we put on these computers that give them extra abilities.

**Client** computers get **client software** that enables them to initiate HTTP conversations and send requests. **Server** computers get **server software** that enables them to wait for clients to initiate conversations and respond to requests. Client and server software is also known under different names: **frontend** and **backend** software.

In this module, we will focus on the new concepts we need for **backend** programming. Backend software enables servers to respond to requests, but there are also a few other things that only the backend can do.

### Why would I use a *backend*?

:::info lecture

Ce sera à la charge du serveur de notamment :

- accéder à la base de données

- authentifier les utilisateurs

- ...etc

:::

- **Databases**:

Gmail has a huge database of all of your emails.

- **Keep track of users**

Facebook needs to know who you are before you can make a post.

- **Business logic in my application**

Amazon needs to keep track of your shopping cart. We can add items, remove items, choose payment methods, and much more.

All these tasks are made possible by writing *backend* software for our Web applications.

:::info lecture

C'est grâce à Node.js que nous pourrons faire cela.

:::

## Node HTTP Server

:::info lecture

cf. https://hackmd.io/@abernier/SJQHMBZ2S

:::

<div class="skip">

Now that we have some basic concepts of servers and backend, **we can make our first server program**. Let's make our first server program using Node!

Let's start by creating a folder with our `server.js` file.

```shell

$ mkdir node-http-server

$ cd node-http-server

$ touch server.js

```

:::warning

:dizzy_face: Don't worry if this code doesn't make much sense to you. In backend programming, you can make a program from scratch but it's far easier to **use a framework**. We will talk about that in the next lesson.

:::

In our `server.js` file we will add the following code:

```javascript=

const http = require('http');

const server = http.createServer();

server.listen(3000);

```

Here we are using the `http` package built-in to Node.js. It has methods for dealing with HTTP. In this case, our goal is to write a program for a server that can **listen for requests** from a client and send responses.

To make our program work, we are creating a server object. It's through the Node.js server object that we can respond to requests. Let's run our application now:

```shell

$ node server.js

```

Unlike previous programs we've created in Node.js, this one doesn't immediately exit back to your normal terminal prompt. Instead, it will run until we stop it manually. This is exactly what we want because our program needs to be running to **respond to requests**.

:::info

💡 To stop the server, use the `CONTROL + C` keyboard shortcut in the terminal.

:::

Our server isn't quite ready to respond to requests just yet. This is our first backend program, so we need to get it to the point where we can make it say _Hello, world!_.

```javascript=

const http = require('http');

const server =

http.createServer((request, response) => {

response.write('Hello, world!');

response.end();

});

server.listen(3000);

```

Here we've added your best friend, a callback. This time, we are using the new arrow function syntax but it's still a callback function. This callback function receives two parameters from the `http` package: `request` and `response`. These are both objects that represent the **request** we received from a client and the **response** we will send back from our server.

The `response` object has methods that allow us to control what a client receives from us. Right now clients will always get the same thing: _Hello, world!_.

:::info

💡 To run the updated `server.js`, use the `CONTROL + C` keyboard shortcut to stop the previous version of the server and run it again with `node server.js`.

Later we will use a tool to do this automatically.

:::

Now that we have our backend _Hello, world!_ running, we can see the result by visiting [localhost:3000](http://localhost:3000). **localhost** is a special domain name that always goes to the special IP address `127.0.0.1`. Both **localhost** and `127.0.0.1` refer to your computer.

`3000` is the **port** of the connection. Servers use that number to route connections to different programs. Think of it like the mailbox number of a post office box. On the last line of our program we specified that our program's **port** is `3000`. All _mail_ that arrives at this computer that says `3000` belongs to our program.

:::info

The default **port** for HTTP requests is `80` (`443` for _https_ URLs). For example, [google.com:80](http://google.com:80) and [https://google.com:443](https://google.com:443) both work. If you try a different number, it will only work if Google's server is set up to handle it.

:::

Visiting [localhost:3000](http://localhost:3000) allows us to see the _Hello, world!_ sent from our server. No matter what URL we visit, if it starts with `localhost:3000` we will always get the same response. Try to visit [localhost:3000/pizza](http://localhost:3000/pizza) or [localhost:3000/shopping](http://localhost:3000/shopping).

To solve this problem, the next thing we should add is a 404 page. If you think about it, we only really have our homepage (the one that says _Hello, world!_. Any URL other than [localhost:3000](http://localhost:3000) should result in a 404.

```javascript=

const http = require('http');

const server =

http.createServer((request, response) => {

console.log(`Someone has requested ${request.url}`);

if (request.url === '/') {

response.write('Hello, world!');

response.end();

}

else {

response.statusCode = 404;

response.write('404 Page');

response.end();

}

});

server.listen(3000);

```

Here we use `request.url` to check which URL the client is asking for to decide which content to send. The `request` object contains a lot of information about the client's request: which URL the are asking for, the kind of browser they are using and any other information that they are sending (more on sending information in a later lesson).

You may have noticed that we are printing a message that includes `request.url` with `console.log()`. Like with other Node.js programs, this `console.log()` will show up in the **terminal** and _not_ in the browser's Console tab. Remember, this JavaScript is running on the server and not in our browser (the client).

Now visit different URLs on your server again and see the new messages in your terminal:

- [localhost:3000](http://localhost:3000)

- [localhost:3000/pizza](http://localhost:3000/pizza)

- [localhost:3000/shopping](http://localhost:3000/shopping)

For bonus points, open your Network tab on the browser before you visit the pages.

:::info

💡 Rember to `CONTROL + C` to stop the previous version of the server and run it again with `node server.js`.

:::

Notice that the `request.url` of [localhost:3000](http://localhost:3000) is actually `/`. We call that the **root** URL of the domain. It's short for [localhost:3000/](http://localhost:3000/). The `request.url` of [localhost:3000/pizza](http://localhost:3000/pizza) is `/pizza`. Referring to URLs **without the domain or the port** is actually very useful so we can write code that works both on [localhost:3000](http://localhost:3000) and (later) on a real domain like [mycoolwebsite.com](http://mycoolwebsite.com). Remember that real domains use the default HTTP port of `80` or `443` ([mycoolwebsite.com:80](http://mycoolwebsite.com:80) or [https://mycoolwebsite.com:443](https://mycoolwebsite.com:443)).

If we were to imagine the HTTP conversation that's going on now it would be something like this for the homepage:

> **Client** _calls localhost:3000_

> **Client** - Hi

> **Server** - Hi

> **Client** - Can you get me `/`? (_this is the request_)

> **Server** _thinks_

> **Server** - Okay! Here it is.

> **Server** _sends `Hello, world!`_ (_this is the response_)

> **Server** _hangs up_

This is what it would look like for any other URL:

> **Client** _calls localhost:3000_

> **Client** - Hi

> **Server** - Hi

> **Client** - Can you get me `/shopping`? (_this is the request_)

> **Server** _thinks_

> **Server** - Not found! Sorry I don't have that.

> **Server** _sends `404 Page`_ (_this is the response_)

> **Server** _hangs up_

Finally, let's add a second real page to our server. We will add an _About Me_ page at [localhost:3000/about](http://localhost:3000/about). Because we want to represent new pages in our code _without_ the domain or the port, our URL will be just `/about`.

```javascript=

const http = require('http');

const server =

http.createServer((request, response) => {

console.log(`Someone has requested ${request.url}`);

if (request.url === '/') {

response.write('Hello, world!');

response.end();

}

else if (request.url === '/about') {

response.write('My name is Izzy');

response.end();

}

else {

response.statusCode = 404;

response.write('404 Page');

response.end();

}

});

server.listen(3000);

```

Now visit [localhost:3000/about](http://localhost:3000/about) and it should work!

:::info

💡 Rember to `CONTROL + C` to stop the previous version of the server and run it again with `node server.js`.

:::

### Downsides of Node HTTP

That wasn't bad for our first backend code, but there are many limitations to doing things from scratch like he just did.

1. **Doesn't work for real HTML** - The "HTML" in our three pages wasn't very complicated, but we now know that even the simplest of Websites has hundreds of lines of HTML. If we put all that HTML inside our `response.write()` strings, we would have the biggest `if..else` statement in the world.

2. **What about CSS & images?** - In this simple server, every resource we want browsers to be able to access needs a new `else if`. Can you imagine having our entire CSS in there too? And what about images? It would take a lot more setup for those very normal needs to be met.

3. **Doesn't scale well** - Your average Website has dozens and dozens of different pages that users can visit. This approach of having each page be its own `else if` doesn't scale well for a lot of pages. We will end up with, again, the biggest `if..else` statement in the world. The code would not be organized, clean, readable or any of the good things we want the code to be.

In the next lesson, we will talk about how certain npm packages can help us solve these problems and many more! Building from scratch is **only useful for educational purposes**. It makes little sense for a real project.

</div>

## Summary

In this lesson, we covered a lot of important ground for backend programming. First, we talked a little about the concepts that make the Internet work. The Internet is just a **bunch of computers connected together** with actual cables (some of which are under the ocean). Some of those computers are **servers** because they provide content. Most of the computers are **clients** because they consume content. When a client wants to get content from a server, it makes a **request** to the server and the server sends a **response**.

Computers connect to each other using **HTTP**. To start an HTTP _conversation_ you need the server's IP address or (more likely) its domain. Domains only work thanks to **DNS** translating the domain name into an IP address for us.

Finally, we talked about the concept of **backend** programming: the code that runs on servers to make them do all that cool server stuff. We even wrote our own first backend programming using Node's `http` module. It wasn't very sophisticated, but it worked!

## Extra Resources

- [Submarine Cable Map Website](https://www.submarinecablemap.com/)

- [What is DNS?](https://www.cloudflare.com/learning/dns/what-is-dns/)

- [An overview of HTTP](https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/HTTP/Overview)

- [Anatomy of an HTTP Transaction (Node.js)](https://nodejs.org/en/docs/guides/anatomy-of-an-http-transaction/)