---

tags: ironhack, lecture,

---

<style>

.markdown-body img[src$=".png"] {background-color:transparent;}

.alert-info.lecture,

.alert-success.lecture,

.alert-warning.lecture,

.alert-danger.lecture {

box-shadow:0 0 0 .5em rgba(64, 96, 85, 0.4); margin-top:20px;margin-bottom:20px;

position:relative;

ddisplay:none;

}

.alert-info.lecture:before,

.alert-success.lecture:before,

.alert-warning.lecture:before,

.alert-danger.lecture:before {

content:"👨🏫\A"; white-space:pre-line;

display:block;margin-bottom:.5em;

/*position:absolute; right:0; top:0;

margin:3px;margin-right:7px;*/

}

b {

--color:yellow;

font-weight:500;

background:var(--color); box-shadow:0 0 0 .35em var(--color),0 0 0 .35em;

}

.skip {

opacity:.4;

}

</style>

# ES6 | Basics and a bit more

## Learning Goals

After this lesson you will:

* Understand what **hoisting** and **scope** are

* Understand a bit more the new variable declaration approaches in ES6, and what kinds of **scopes** there are in JavaScript

* Get more familiar with **string interpolation** in **template literals**

* Understand **destructuring** and the **spread operator**

## Recap - Intro to ES6

:::info lecture

Javascript connait de nombreuses évolutions, notamment en 2015 avec ES6.

:::

In [JavaScript Intro](http://learn.ironhack.com/#/learning_unit/6369) lesson we spoke about [ECMAScript](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ECMAScript) and how we came to `ES2015` or more popularly called, `ES6`.

Let's recap shortly:

:::info lecture

ECMAScript est un peu la norme ISO du Javascript.

:::

JavScript was created in 1995. and since then, it's been through a lot of changes. [ECMA International](http://www.ecma-international.org/) has made all these changes standardized. ECMA International is a global organization that aims to create standards for computer systems. Created in 1961, they have defined many important specifications for common technologies, such as:

:::info lecture

ECMA interational, c'est aussi une gamme variée de standardisations :

:::

- ASCII - text encoding

- CD-ROM, Floppy disks, etc

- JSON

- and many programming languages! ie. C++, Dart...

One of their most popular specifications is known as [ECMAScript](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ECMAScript) (ES), which is their trademark name for JavaScript.

:::info

ECMAScript is the standard and JavaScript is its most popular implementation.

:::

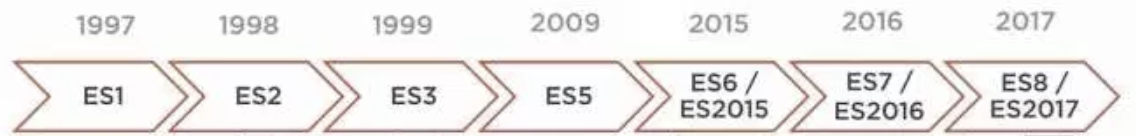

On the following chart, we can see the evolution of JavaScript:

:::info lecture

Les différentes versions du language (☝️toujours rétro-compatibles) :

:::

:::info lecture

Compatibility table :

[](http://kangax.github.io/compat-table)

-> babel

:::

:::info lecture

Avec ES6, en plus de `var` nous avons maintenant `let` et `const` pour déclarer des variables. Re-voyons ce que cela change en terme de portée de variables...

:::

One of the most significant changes in ES6 was introducing a new way of declaring variables, using `let` and `const` keywords and these also brought to a play a different `scope` than the ones we used to have with `var`.

Before we move forward, let's make sure everyone understands:

:::success

A **scope** represents where a declared variable is available to be used, or better saying - accessed.

:::

Let's break it down a bit.

## `var`, `let`, `const`, and **scope**

### The case of **var**

Before the ES6, all variables were declared using `var` keyword. Declaring the variables this way has some specifics:

#### `var` and **hoisting**

:::info lecture

Le hoisting est un mécanisme qui va rassembler les déclarations de variables tout en haut du scope.

:::

:::info

**Hoisting** is a JavaScript mechanism where **variables and function declarations are moved to the top of their scope before code execution**.

:::

:::info lecture

Ainsi, si l'on essaye d'accéder à une variable AVANT sa déclaration :

```jsx

console.log(toto); // ReferenceError ?

var toto = 2;

```

En fait non, pas d'erreur, nous n'aurons pas d'erreur mais `undefined`, car le hoisting s'applique :

```jsx

// var toto; 👈 hoisting

console.log(toto);

var toto = 2;

```

:::

:::info lecture

C'est CE MECANISME qui permet en fait de par ex utiliser une fonction avant (dans le code) qu'elle ne soit déclarer :

```jsx

hey();

function hey() {

console.log("coucou");

}

```

:::

This means you can use the variable in the parts of your code before you declared it officially:

```javascript

console.log(message); // <== undefined

var message = "Hello from the global scope!";

```

**Variables declared using `var` are moved to the top if it's scope (we say - hoisted) and initialized with a value of `undefined`**.

#### `var` and the **scope**

:::info lecture

Une variable `var` est scopée dans sa fonction. Elle n'existera pas en dehors.

:::

:::warning lecture

Si pas de fonction autour d'une variable `var` => globale.

C'est ce qui nous a permis dans le jeu de *communiquer* des variables entre les fichiers :

```jsx

// main.js

var $canvas = document.querySelectory('canvas');

var W = $canvas.width; // 👈 GLOBALE

```

```jsx

// obstacle.js

class Obstacle {

constructor() {

this.x = W/2; // 👈 ACCES à W

}

}

```

PS: l'objet global est en réalité (coté navigateur) `window`.

:::

:::success

Using keyword **`var`** to declare variables, they become available in:

- **global** or

- **function/local** scope.

:::

:::info

To simplify, any time a variable is declared outside of a function, it belongs to the **global scope** and can be accessed (used) in the whole window.

If we declare a variable inside the function, then the variable belongs to the **functional or local scope**.

:::

Let's see it on the example:

:::info lecture

Regardons cet exemple:

:::

```javascript=

var message = "Hello from the global scope!";

function sayHelloFromLocalScope(){

var greeting = "Hello from functional/local scope!";

return greeting;

}

console.log(message); // <== Hello from the global scope!

console.log(greeting); // <== ReferenceError: greeting is not defined

```

:::info lecture

- L1: `message` est globale

- L4: `greeting` est scopée dans `sayHelloFromLocalScope` et n'existe donc pas en dehors => `ReferenceError` L9

:::

As we can see, `message` belongs to the **global scope and can be accessed from anywhere** in the code. In the second example, the `greeting` variable is **functionally/locally scoped and can't be accessed outside of the function where it was declared**.

:::warning

This *doesn't apply* to *if statements* and *for loops*. They don't have their scope.

:::

:::warning lecture

Bien sur, une boucle n'étant pas une fonction, une variable déclarée dans une boucle ne sera pas locale à la boucle :

:::

```javascript

for (var i = 1; i <= 30; i++) {

console.log(`Iteration number: ${i}`);

}

console.log(`After the loop: ${i}`);

// [...]

// Iteration number: 28

// Iteration number: 29

// Iteration number: 30

// After the loop 31

```

:::danger lecture

⚠️ Implied global

Une variable assignée mais **non-déclarée devient implicitement globale** :

```jsx

function foo() {

x = 0; // x devient implicitement globale (pour le reste du programme)

}

```

Ce peut être très dangereux, comme dans cet exemple :

```jsx

for (i = 0; i < 10; i++) {

…

}

```

Si 2 fichiers JS utilisent la même variable globale, l'un risque de modifier la valeur pour l'autre.

:::

#### Using `var` variables **can be re-declared and updated**

:::info lecture

Un propriété intéressante des variables `var` est qu'elles peuvent être **re-déclarées** + **ré-assignées**.

:::

The following won't cause the error:

```javascript

var message = "Hello from the global scope!";

var message = "This is the second message.";

// OR

var message = "Hello from the global scope!";

message = "This is the second message.";

```

But is this necessarily a good thing? Let's see:

:::warning lecture

Par contre, ça ne nous arrangera pas tout le temps :

:::

:::warning

```javascript=

var name = "Ironhacker";

if (true) {

var name = "Ted";

console.log(`Name inside if statement: ${name}`);

}

console.log(`Name outside if statement: ${name}`);

// Name inside if statement: Ted

// Name outside if statement: Ted

```

:::

:::info lecture

Ici, par ex, L3 : name est re-déclarée et l'anciene valeur en L1 est perdue.

:::

As we can see from the example above, variable *name* is re-declared, and if we didn't know that there's already a variable *name* declared earlier, we could've broken bunch of things.

If we use the same variable throughout our code, and we reassign it like we just did, we won't see the results we expected for sure. That's why `let` and `const` are here to prevent this and we will see now how.

### The case of **`let`** and **`const`**

:::info lecture

`let` et `const` vont nous permettre d'autres choses...

:::

In general, `let` and `const` came to fix the issues `var` have had.

#### **`let`** and **hoisting**

:::info lecture

SUBTIL

Comme pour `var`, les variables `let` sont aussi hoistés (en haut de leur scope). Cependant, on ne pourra pas "utiliser" la variable avant dans le code. Sinon, on aura un `ReferenceError`.

:::

There's a slight difference between `var` and `let` when it comes to hoisting: variables declared with *let* are hoisted to the top as well but they are not initialized. So using *var* we would get the value of *undefined* but using *let* we get a *Reference Error*.

According to the official docs, the reason for that is:

:::info

`let` and `const` (read the lesson further to understand the *const* part) hoist but you cannot access them before the actual declaration is evaluated at runtime.

:::

#### **`let`** and **`const`** and **block scope**

:::info lecture

Plus intéresant, le scope de `let` et `const` est **le block** (non plus la fonction).

:::

:::info

We can say that **block is any code between open and closed curly braces `{}`**.

:::

:::info

**`let`** gives us **`block scoping`**, is _not_ bounded to the `global` or `window` object by default, and should be used in favor of `var`.

:::

If we replace `var` with `let` in one of the previous examples, we will get a different result.

:::info lecture

Nous le voyons dans cet ex, où `i` n'existe qu'à l'intérieur du block `for {}`. Après ce block, `i` n'existe pas.

:::

```javascript

for (let i = 1; i <= 30; i++) {

console.log(`Iteration number: ${i}`);

}

console.log(`After the loop: ${i}`);

// [...]

// Iteration number: 29

// Iteration number: 30

// Iteration number: 30

//

// console.log("After the loop", i);

// ^

// ReferenceError: i is not defined

```

:+1: Sometimes *errors are ok*. `let` can help us prevent some JavaScript pitfalls, by throwing an error back at us.

:::info

As we can see, `let` gives us the **block** scope which means that variable declared in a block using *let* can be only used in that block. Blocks also include *if* statements and *for* loops as well as functions.

:::

:::info lecture

En règle générale, nous préfèrerons utiliser `let` à `var`, car elle sera plus locale. (en général, ie: pas toujours 😆).

:::

#### Using **`let`** variables **can't be re-declared but can be updated**

:::info lecture

- Contrairement à `var`, `let` ne peut **PAS être re-déclarée** : cf. L8

- Par contre, elle **peut être ré-assignée** : cf. L3

:::

```javascript=

// THIS IS OKAY ✅✅✅

let message = "This is the first message.";

message = "This is the second message."; // <== This is the second message.

// BUT THIS WILL THROW AN ERROR 🚨🚨🚨

let message = "This is the first message.";

let message = "This is the second message."; // <== Duplicate declaration "message"

```

:::info lecture

Par contre, c'est ok de re-déclarer une variable dans un autre scope, comme par ex ici L8 :

:::

```javascript=

// HOWEVER, IF THE SAME VARIABLES BELONG TO DIFFERENT SCOPES,

// NO ERROR WILL BE SHOWN BECAUSE THEY ARE TREATED AS DIFFERENT VARIABLES

// WHICH BELONG TO DIFFERENT SCOPES

let name = "Ironhacker";

if (true) {

let name = "Ted";

console.log(`Name inside if statement: ${name}`);

}

console.log(`Name outside if statement: ${name}`);

// Name inside if statement: Ted

// Name outside if statement: Ironhacker

```

To recap and compare: `let` gives us much more security because when variables are declared with `let`, if declared in different scopes, are two different variables while using `var` the second one will redeclare the first one. At the same time, `let` doesn't allow having the same named variables in the same scope while, as we saw, with `var` that is possible to happen and no error will be thrown.

#### Using **`const`** variables **can't be re-declared nor updated**

:::info lecture

- De même que pour `let`, une variable `const` ne peut **PAS être re-déclarée**. cf. L8

- Et contrairement à `let`, elle ne pourra **PAS être ré-assignée** : c'est toute la différence d'avec `let`. cf. L3

:::

The most secure and preferred way of declaring variables is using **`const` - variables declared this way can't be re-declared nor updated**.

```javascript=

// THIS WILL THROW AN ERROR 🚨🚨🚨

const message = "This is the first message.";

message = "This is the second message."; // <== "message" is read-only

// AND THIS WILL THROW AN ERROR 🚨🚨🚨

const message = "This is the first message.";

const message = "This is the second message."; // <== Duplicate declaration "message"

```

:::danger lecture

Du fait qu'une variable `const` ne peut être ré-assignée, on ne pourra pas d'abord la déclarer puis l'assigner.

```jsx

const name;

name = "John" // ERROR

```

Il nous faudra le faire en même temps :

```jsx

const name = "John";

```

:::

:::danger

Variables declared with `const` have to be initialized in the moment of declaration. This will throw an error:

```javascript

const name = "John"; // <== CORRECT

const name; // <== WRONG!

name = "John"; // <== this doesn't work

```

:::

:::success lecture

Par contre, si une variable `const` contient un objet :

```jsx

const me = {

name: "John",

age: 23

};

```

on pourra :

```jsx

me.age = 24;

```

car ce n'est pas ici `me` que l'on ré-assigne mais bien la propriété `age` de `me`.

:::

We saw in the case of objects and arrays declared using *const*, we can update the existing properties.

A quick reminder:

:::info

In the case of declaring an object using the `const` keyword, this means that new properties and values can be added BUT the value of the object itself is fixed to the same reference (address) in the memory and the object (or any variable declared with const) can’t be reassigned.

:::

```javascript

// This is ok ✅

const obj = {};

obj.name = "Ironhacker";

// This is not 🚨

obj = { name: "Ironhacker" };

// SyntaxError: Assignment to constant variable

```

### Summup

:::info lecture

Pour résumer :

:::

:::info

🤔 *Potential interview questions*:

<br>

| | hoisted/initialized | scope |updated |redeclared |

|:---: |:---: |:---: |:---: |:---: |

| var | ✅/✅ |global or functional(local)|✅ |✅ |

| let | ✅/❌ |block |✅ |❌ |

| const | ✅/❌ |block |❌ |❌ |

⭐️ `var` and `let` can be declared and later on initialized.

⭐️ `const` have to be initialized when declared.

:::

## Template Strings

In [Data Types in JavaScript - number & string](http://learn.ironhack.com/#/learning_unit/7872) we mentioned that one of the ways of creating strings is using backticks ` `` `, and also in the majority of console logs we used *string interpolation using backticks* but now let's dig a bit deeper.

:::success

**Template literals** are string literals allowing embedded expressions.

:::

Strings in JavaScript have been historically limited. [ES6 Template Strings](https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/JavaScript/Reference/Template_literals) introduces an entirely different way of solving these problems.

### Interpolation

Template Strings use back-ticks (``) rather than the single or double quotes. The following example shows how we can write a template string:

```javascript

let greeting = `Yo, Ironhack!`;

```

:::info lecture

interpolation de string en utilisant la syntax `${}` dans les backticks.

:::

One of their first real benefits is **string substitution**. Substitution **allows us to take any valid JavaScript expression and place it inside a template literal, and the result will be output as part of the same string**.

Template Strings can contain placeholders for string substitution using the **`${ }` syntax**, as demonstrated below:

```javascript

let awesomePlace = "Ironhack";

let greeting = `Yo, ${awesomePlace}!`;

console.log(greeting);

// => "Yo, Ironhack!"

```

The `${}` syntax works fine with any kind of expression. Check the following example:

**ES5 Old-school style!!**

:::info lecture

AVANT

:::

```javascript

var customer = { firstName: "Foo", lastName: "Kim" };

var message = "Hello " + customer.firstName + " " + customer.lastName + "!!";

console.log(message);

```

**ES6 Interpolation style!!**

:::info lecture

APRES

:::

```javascript

let customer = { firstName: "Foo", lastName: "Kim" };

let message = `Hello ${customer.firstName} ${customer.lastName}!!`;

console.log(message);

```

As you can see, this kind of interpolation using template literals makes our code much more readable and cleaner!

#### Multiline Interpolation

:::info lecture

permet également le multiligne : intéressant par ex pour écrire du HTML:

```jsx

let html = `

<div>

<p>Bonjour</p>

</div>

`;

```

:::

Multiline strings in JavaScript require workarounds using regular ways of interpolation. The current solution is just using a `\`(backslash) before each newline. Super easy! For example:

```javascript

let greeting = "Yo, Joey! \

How are you doing?";

```

Also, any whitespace inside of the backtick syntax will be considered part of the string and it will help you organize your multiline strings.

```javascript

console.log(`string text line 1

string text line 2`);

```

### ES6 new string methods

:::info lecture

De nouvelles fonctionnalités

:::

#### `startsWith()` method

The `startsWith()` method determines whether a `string` begins with the characters of a specified string, returning `true` or `false` as appropriate.

It's important to remember that this method is case-sensitive.

**Syntax**

:::info

```

str.startsWith(searchString[, position])

```

- **`searchString`** - the characters to search at the start of this string,

- **`position`** (optional) - the position in this string at which to begin searching for `searchString` (the default is 0).

:::

**Example**

```javascript

const str = "To be, or not to be, that is the question.";

console.log(str.startsWith("To be")); // true

console.log(str.startsWith("not to be")); // false

console.log(str.startsWith("not to be", 10)); // true

```

#### `endsWith()` method

The `endsWith()` method determines whether a string ends with the characters of a specified string, returning `true` or `false` as appropriate. It's also case-sensitive.

**Syntax**

:::info

```

str.endsWith(searchString[, length])

```

- **`searchString`** - the characters to search at the start of this string,

- **`length`** (optional) - if provided, overwrites the considered length of the string to search in. If omitted, the default value is the length of the string.

:::

**Example**

```javascript

const str = "To be, or not to be, that is the question.";

console.log(str.endsWith("question.")); // true

console.log(str.endsWith("to be")); // false

console.log(str.endsWith("to be", 19)); // true

```

#### `includes()` method

:::info lecture

Plutôt que de

```jsx

if (str.indexOf("Julie") !== -1) {

…

}

```

on peut maintenant éviter une négation :

```jsx

if (str.includes("Julie")) {

…

}

```

:::

The `includes()` method determines whether one string may be found within another string, returning `true` or `false` as appropriate. The method is case sensitive.

**Syntax**

:::info

str.includes(searchString[, position])

- **searchString** - the characters to search for at the start of this string,

- **length** (optional) - the position within the string at which to begin the search (defaults to 0).

:::

**Example**

```javascript

const str = "To be, or not to be, that is the question.";

console.log(str.includes("to be")); // true

console.log(str.includes("question")); // true

console.log(str.includes("nonexistent")); // false

console.log(str.includes("To be", 1)); // false

```

## Object and Array Destructuring

:::success

**Destructuring** is an easy and convenient way of extracting data from arrays and objects.

:::

The problem is that in ES5 this was very verbose.

### Objects

Let's say we have a person object.

:::info lecture

Voici comment nous faisons SANS destructuring :

:::

```javascript=

let person = {

name: "Ironhacker",

age: 25,

favoriteMusic: "Metal"

};

let name = person.name;

let age = person.age;

let favoriteMusic = person.favoriteMusic;

console.log(`Hello, ${name}.`);

console.log(`You are ${age} years old.`);

console.log(`Your favorite music is ${favoriteMusic}.`);

```

:::info lecture

L7 on déclare une variable `name` et on l'assigne à la valeur de la propriété du même nom que `person`.

Idem pour `age` et `favoriteMusic`.

:::

This is ok, but didn't we repeat the word `person` multiple times here? Yes, we did. And as developers, we don't like to repeat things because we want our code to be DRY, clean and neat. So let's do the same but using `object destructuring`.

:::info lecture

Tout ceci est parfaitement ok.

Mais nous allons avoir un raccourci pour le faire, grâce au destructuring :

:::

```javascript=

let person = {

name: "Ironhacker",

age: 25,

favoriteMusic: "Metal"

};

let { name, age, favoriteMusic } = person;

console.log(`Hello, ${name}.`);

console.log(`You are ${age} years old.`);

console.log(`Your favorite music is ${favoriteMusic}.`);

```

:::info lecture

L7 maintenant regroupe L7, L8 et L9 en une seule : nous créons 3 variables et les assignons à la valeur des propriétés correspondantes dans l'objet `person`.

---

Par ex:

<span style="font-size:200%">`const { 🔧, 🔩 } = 🧰`</span>:

```jsx

const boiteOutils = {

marteau: "je suis un marteau",

tenaille: "je suis une tenaille",

clef: "je suis une clef",

tournevis: "je suis un tournevis",

ecrou: "je suis un ecrou"

};

const {clef, ecrou} = boiteOutils;

console.log(clef, ecrou);

```

:::

Awesome.

:::info

What we're doing is creating variables using the same names as the properties of our object.

:::

JavaScript breaks it apart and assigns these values to the new variables.

We can even get to nested objects:

```javascript

const person = {

name: "Ironhacker",

age: 25,

favoriteMusic: "Metal",

address: {

street: "Super Cool St",

number: 123,

city: "Miami"

}

};

let {

name,

age,

favoriteMusic,

address

} = person;

console.log(address.street); // <== Super Cool St

```

### Arrays

:::info lecture

Le desctructuring est aussi possible pour les tableaux...

:::

Array destructuring is very similar.

:::info

First, we declare our variable(s) inside of array brackets and then assign them to the one we're trying to destructure.

:::

:::info lecture

Considérons `numbers` :

:::

```javascript

const numbers = ["one", "two", "three", "four", "five"];

```

**Examples:**

* Put the first item in the array in a variable

:::info lecture

Une variable `first` valant le premier élément de `numbers` :

:::

```javascript

const [first] = numbers;

console.log(first); // <== one

```

* Take the first 3 items in the array

:::info lecture

Trois variables `first`, `second`, `third` valant respectivement le premier, deuxième et troisième élément de `numbers` :

:::

```javascript

const [first, second, third] = numbers;

console.log(first, second, third); // <== one two three

```

* Skip the first element, and take the second one only

:::info lecture

Ou même que le 2e :

:::

```javascript

const [, second] = numbers;

console.log(second); // <== two

```

<div class="skip">

ES6 uses *fail soft destructuring* by default meaning that if there are more variables than items in the array, it won't throw an error, it will just be undefined.

```javascript

// Whoops, we only have one element in the array!

const [a, b] = [1];

console.log(a * b); // <== a * undefined => NaN

```

We can combine this with default arguments to make sure we always have values in our variables.

```javascript

const [a, b = 1] = [2];

console.log(a * b); // <== 2

```

#### Quick Exercise

**What's the result? And more importantly, why?**

```javascript

let [a, b = 2, c, d = 1] = [3, 4];

console.log(a, b, c, d);

```

</div>

## Spread Operator

:::info lecture

Nous avons [déjà vu](https://hackmd.io/@abernier/BJu4SImur#How-to-copy-an-object) que le spread operator nous permet de créer une shallow-copy d'un tableau/objet :

```javascript

const = book1 = {

author: "Charlotte Bronte"

};

const book2 = { ...book1, author: "Julie" }; // shallow-copy of book1

```

```javascript

const ironhackers = [ ...students, {name: 'Billy'} ]

```

:::

One of the new ES6 features is the **spread operator**. It is a small change, but it can be useful on different occasions.

Let's take a look at an example of how to use the spread operator.

Let's say we have these two arrays, one with reptiles, and one with mammals.

```javascript

const reptiles = ["snake", "lizard", "alligator"];

const mammals = ["puppy", "kitten", "bunny"];

```

Now let's say we want to create a new array called `animals` that has all of the reptiles and all of the mammals. How would we do that?

Well, without using the spread operator, we would have to do something like this:

```javascript

const animals = [];

reptiles.forEach(oneReptile => animals.push(oneReptile));

mammals.forEach(oneMammal => animals.push(oneMammal));

console.log(animals);

// [ 'snake', 'lizard', 'alligator', 'puppy', 'kitten', 'bunny' ]

```

We run two different loops to push each item from each of the two arrays into `animals` array.

Let's take a look at how we can use the ES6 **spread operator** to accomplish the same thing.

:::info lecture

Ici L3 on crée un tableau `animals` qui sera la réunion des copies respectives de `reptiles` et `mammals` :

:::

```javascript=

const reptiles = ["snake", "lizard", "alligator"];

const mammals = ["puppy", "kitten", "bunny"];

const animals = [...mammals, ...reptiles];

console.log(animals);

// [ 'puppy', 'kitten', 'bunny', 'snake', 'lizard', 'alligator' ]

```

That's it.

So, how does it work?

Well, the spread operator looks like this `...`. It's just three dots.

In this example, we use the spread operator `...` in front of the name of an array - this returns its contents, without the array itself.

## Advanced

### Rest Parameters - Other uses of the Spread Operator

:::info lecture

L'opérateur `...` peut également servir dans les arguments/paramètres d'une fonction...

---

Si l'on souhaite écrire une fonction mais en ne connaissant pas d'avance le nombre de paramètres :

```jsx=

function add(...numbers) {

return numbers.reduce((acc, num) => acc + num);

}

console.log(add(1,2,3)); // 6

console.log(add(1,2,3,4,5,6,7)); // 28

```

L1 : `...numbers` transformera l'ensemble des paramètres transmis en un tableau

:::

<div class="skip">

The other way we make use of the spread operator is to use it in the definition of a function. It is known as [Rest parameters](https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/JavaScript/Reference/Functions/rest_parameters).

❗The rest parameter syntax allows us to represent an indefinite number of arguments as an array.

We commonly write functions like this

```javascript

function myFunction(arg1, arg2) {

console.log(arg1);

console.log(arg2);

}

```

If we call this function like this

```javascript

myFunction("first argument", "second argument");

```

We get this:

```

first argument

second argument

```

Great, we have two arguments and we see them in the console. But what if we don't know how many arguments we are going to have? What if we call the same function with an extra argument, what happens?

```javascript

myFunction("first argument", "second argument", "third argument");

```

This code will give us

```

first argument

second argument

```

Our program will completely ignore the 3rd argument because it is not part of the definition of our function.

There's a workaround this:

```javascript

function add() {

let sum = 0;

for(let i = 0; i < arguments.length; i++) {

sum += arguments[i];

}

return sum;

}

add(); // 0

add(1); // 1

add(1, 2, 5, 8); // 16

```

:::info

:bulb: **arguments** is kind of magic word here: it represents a special `array-like` object that contains all arguments by their index.

:::

If we were to console.log() arguments in the previous example in the case `add(1, 2, 5, 8);`, we would have seen this:

```javascript

...

console.log(arguments);

...

// { 0: 1, 1: 2, 2: 5, 3: 8 }

```

So it looks okay, why do we need a rest parameter then?

Well, let's try to apply `.reduce()` instead 'manually' calculating the sum. (If you need to sneak peek how `.reduce()` works, check [Arrays - Map, Reduce & Filter](http://learn.ironhack.com/#/learning_unit/6393) lesson.)

```javascript

function add() {

return arguments.reduce((sum, next) => sum + next);

}

add(1, 2, 3); // TypeError: arguments.reduce is not a function

```

We got the error and since we explained earlier what is `arguments`, it is kind of obvious why - because `arguments` is not the array so we can't apply any of its methods.

In order to avoid this kind of situation, we can use the rest parameters in a function definition.

We will use `...` in front of the argument name and they literally mean “gather the remaining parameters into an array”.

Let's see it through example:

```javascript

function add(...numbers) { // numbers is the name for the array

// we will pass in when invoking the function

let sum = 0;

for (let oneNumber of numbers){

sum += oneNumber;

}

return sum;

}

add(1); // 1

add(1, 2); // 3

add(1,2,5,8); // 16

```

And using `.reduce()`, we will have cleaner code:

```javascript

function add(...numbers) { // numbers is the name for the array

let sum = 0;

return numbers.reduce((sum, next) => {

return sum + next;

})

return sum;

}

add (1,2,5,8); // <== 16

```

</div>

:::info lecture

On peut également :

```jsx

function addPow(power, ...numbers) {

return numbers.reduce((acc, num) => acc + num**power, 0);

}

addPow(3, 2,2) // 16

```

:::

❗We can choose to get the first parameters as variables and gather only the rest.

Here the first two arguments go into variables and the rest go into `movies` array:

```javascript

function showMovie(title, year, ...actors) {

console.log(`${title} is released in ${year} and in the cast are: ${actors[0]} and ${actors[1]}.`);

}

showMovie("Titanic", "1997", "Leonardo Di Caprio", "Kate Winslet");

```

## Summary

In this lesson, we learned about the new features of ES6, caused by introducing `const` and `let` and we learned about similarities and differences between declaring variables using `var` vs `let` and `const`. We also learned about **Template strings** features, and `string` methods such as `startsWith()`, `endsWith()`, `includes()`.

Finally, we saw how to use `arrays` and `objects` **destructuring**, and the `spread` operator with `arrays` and `rest` parameters.

Going forward, embrace and apply as many of these features as you can. While one of them on its own might not make a huge difference, all of them together used consistently can create a cleaner, easier to read the code, while avoiding some of the pitfalls of JavaScript.

## Extra Resources

* [MDN `const`](https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/JavaScript/Reference/Statements/const)

* [MDN `let`](https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/JavaScript/Reference/Statements/let)

* [Template Literals](https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/JavaScript/Reference/Template_literals)

* [ES6 Features](http://es6-features.org/)