# SWP Git Tutorial

## Version Control Systems

### _What_ is VCS

A **Version Control System** is a piece of software that tracks and manages changes to a filesystem. It can sometimes provide utilities that help with collaboration as well. Generally speaking, its main functionality is to allow you to keep the history of modifications to your project and inspect it at will.

Examples: Git, CVS, Apache Subversion (SVN)

### _Why_ VCS

VCS allows you to:

- Have a backup of your project at every step along the way

- Find out when a bug was introduced

- Track metrics on the evolution of the code

- Compare different revisions of the same project

- Track who did what changes

- Share your code with someone else

- Experiment with a new feature without breaking the existing codebase

## Git

> _"Git is a [free and open source](https://git-scm.com/about/free-and-open-source) distributed version control system designed to handle everything from small to very large projects with speed and efficiency."_ - https://git-scm.com/

### Why git

Out of the available VCSs, git is:

- Distributed. It doesn't depend on one single source of truth that has full control over the data

- Open source. (nuff said :smirk:)

- Simple, yet extremely powerful

- Makes branching and collaborating a lot easier

- Works on many platforms

### Core concepts

#### Commit

A snapshot that captures the state of the project at that point in time. Contrary to what many people think, every commit takes a snapshot of the entire project; it doesn't just store the diff. However, it simply replaces unchanged files with a pointer to the previous version for efficiency.

> _That's why it doesn't scale nicely with large files, for which you can use the [Git Large File Storage (LFS)](https://git-lfs.github.com/)_

Commits are the building blocks of everything in git. They are also immutable (once created, cannot be changed - you *commit* to it - _ba dum tss_). The _history_, however, is **not** immutable.

Commits are identified through their unique (SHA-1, 40-character) hashes, calculated from the commit info including its content and metadata such as the parent commits, author, message, time, etc...

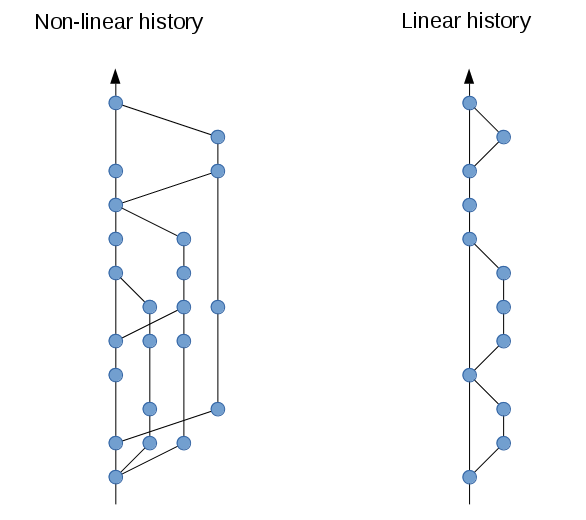

#### History

A collection of commits, stored as a directed acyclic graph (DAG). Some commits might have more than one parent (but typically 2 max) because of merge commits.

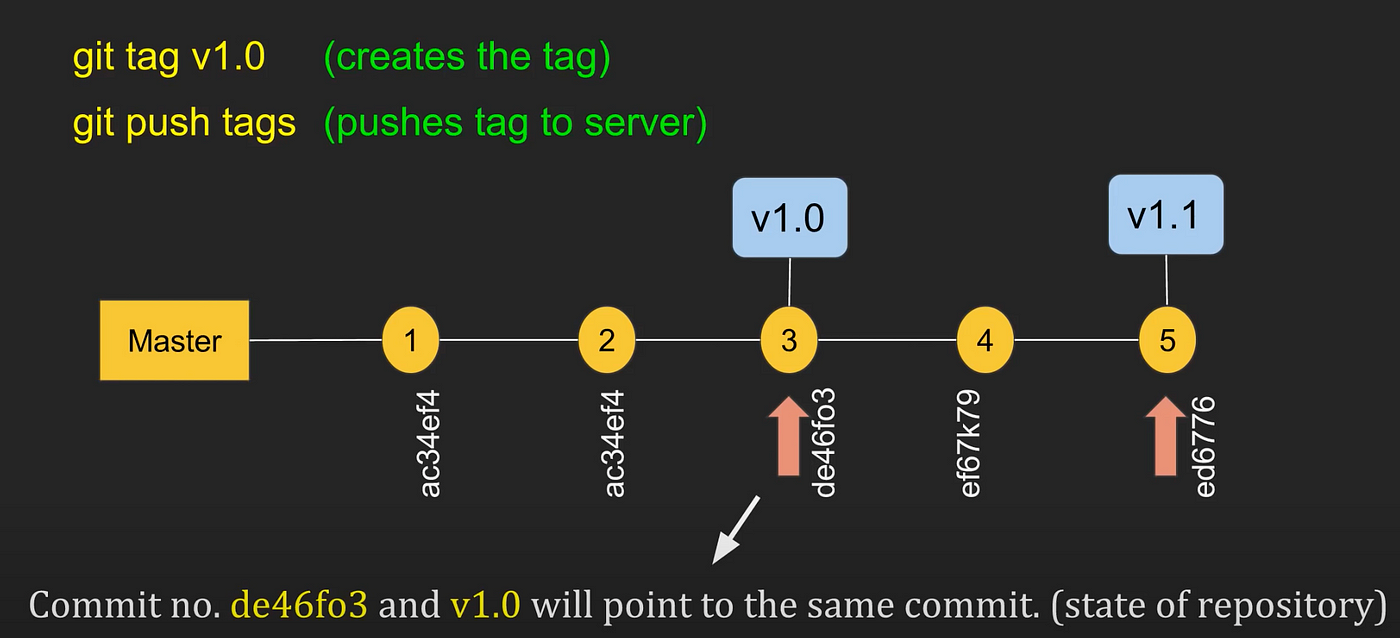

#### Tag

A reference with a human-friendly name given to a particular commit in the history.

#### Branch

Like a tag, but moves with you when you commit.

Usually, all branches will have at least one common anscestor commit, but it doesn't _have_ to be that way (though the image above is a bit misleading).

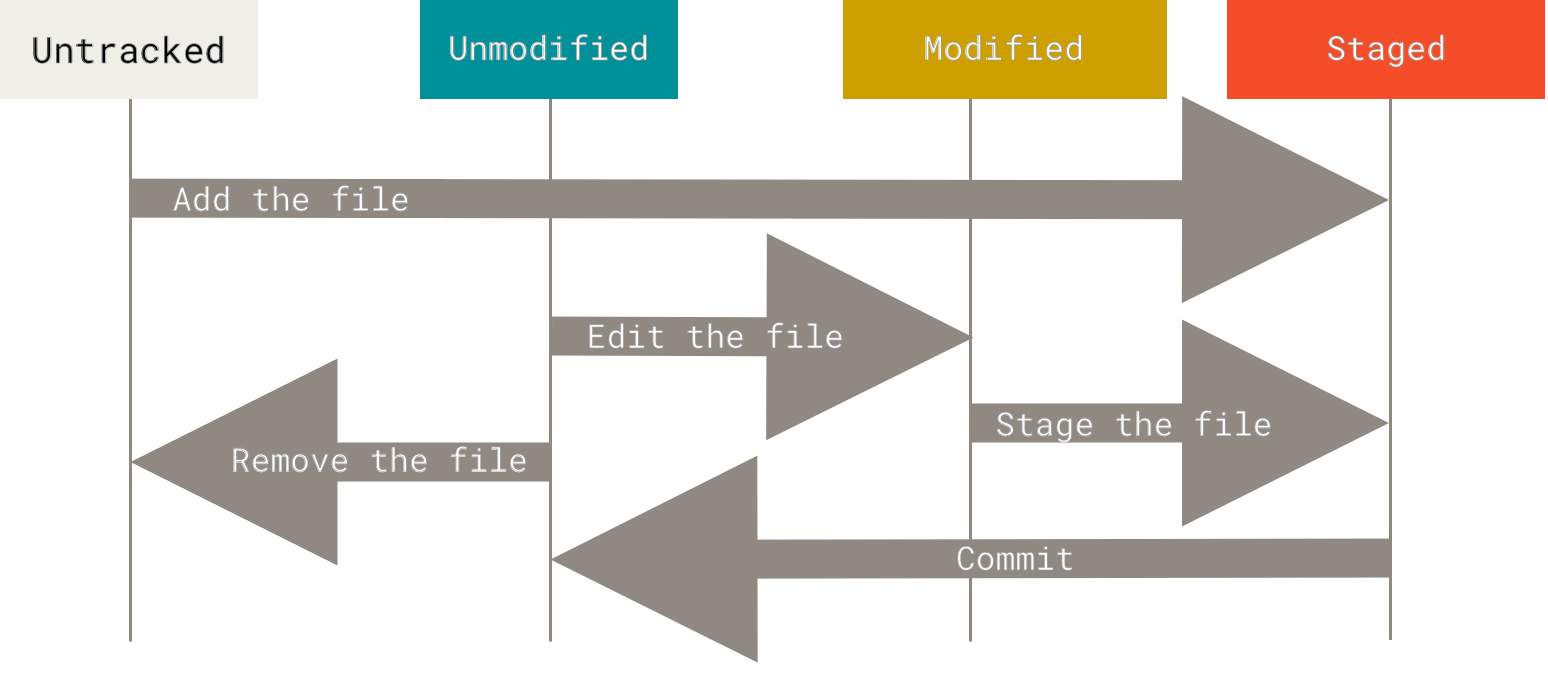

#### Staging area

Part of the interface rather than the data model. It is an intermediate step between the current state of the working directory and the snapshot we want to take (commit).

Think of it like a draft space. Your work doesn't have to be finalized yet, but part of it is good enough, so you just send those parts to the staging area and continue working on the rest.

It is also known as the "index".

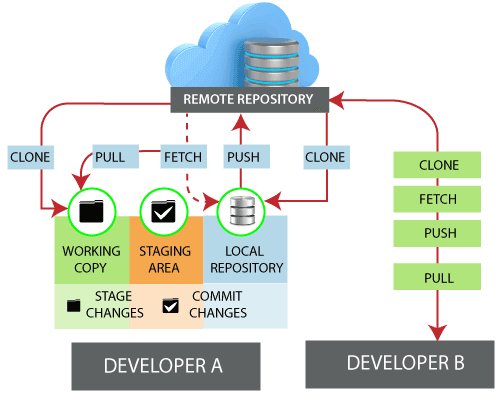

#### Remotes

Remotes are how you do collaboration on git, given that is a distributed system.

Basically, you tell your local git about the addresses of the other collaborators with whom you need to synchronize changes (commits). We call this a remote repo.

It would become tedious to have to register every single coworker, know their IP addresses (which change!), and try to track who has which features and so on, so we typically still depend on a central server that doesn't sleep (such as GitHub, GitLab, BitBucket, or your enterprise's server).

### Other terminology

- Blob: **b**inary **l**arge **ob**ject. Just a file

- Tree: a folder

- Repository: A project directory containing the special `.git` folder which stores metadata about the project

### Basic usage

> _Putting it all together_

You create a new repo in the current directory using `git init`. Alternatively, you can clone an existing repo using `git clone <url>`.

After cloning, you can create branches, modify files in existing branches, and do anything you want with the code.

Then, you stage those stages (add to the index), write a message describing this set of changes, and commit.

Now, you have your local repo in a state that is different to the remote, so you `git push` your changes to synchronize and send your updates to the server. If another developer already changed some files/lines that you also changed, but they pushed first, you will get a merge conflict.

This is why you should `git pull` first and try to fix the conflicts locally (if any).

It's worth noting that the local repo includes what's called **remote-tracking branches**, which are read-only branches that mirror the content of the remote repo. It gets updated automatically whenever you do any network communication, such as `git fetch`. Their names start with the name of the remote, followed by a slash. For example, if you have a branch called `main`, the equivalent branch tracking the remote repo will likely be called `origin/main`.

As a matter of fact, the `git pull` command is actually a shorthand for `git fetch` + `git merge` from the remote-tracking to your local branch.

## GitHub

One of the most popular git services that offers many features on top of just being a git server.

### Issues

Issues are central to the project management features of GitHub. They allow to track the work and keep the relevant communication in one place.

Let's take a look at an example: https://github.com/aabounegm/cast/issues

We can see that an issue consists mainly of a title and body. It can also have assignees, a milestone, and some labels.

Milestones help track progress of a group of issues that are expected to be done by some point in time, while labels are used to categorize the issues and pull requests.

### Pull requests

Pull Requests allow you to submit your changes for review by others. You specify the **head branch** (the branch containing your changes) and the **base branch** (the branch to which you want to merge your changes).

GitLab gives them the more intuitive name: Merge requests.

Collaborators can then examine the changes, comment on them, request additional changes, or approve the merge.

Example: https://github.com/aabounegm/cast/pull/228

### Pages

GitHub Pages allows you to host a static webpage straight from your git repo. You just enable it from the settings and pick a folder/branch that has the HTML files and you're good to go.

See https://pages.github.com/

### Actions

GitHub Actions is used to execute and automate some workflows in response to some events in your repo. Most commonly, it is used to integrate a CI/CD process, such as running unit tests on new code you push or deploying the latest version of the website after the updates are merged to the main branch.

Example: https://github.com/aabounegm/cast/actions

## Workflows

When working in teams, there has to be some agreed-upon workflow for a smooth and intuitive process. We need some rules in order to leverage Git effectively and be productive with it.

When talking about workflows, people usually limit them to "branching strategies", but they are much more than that.

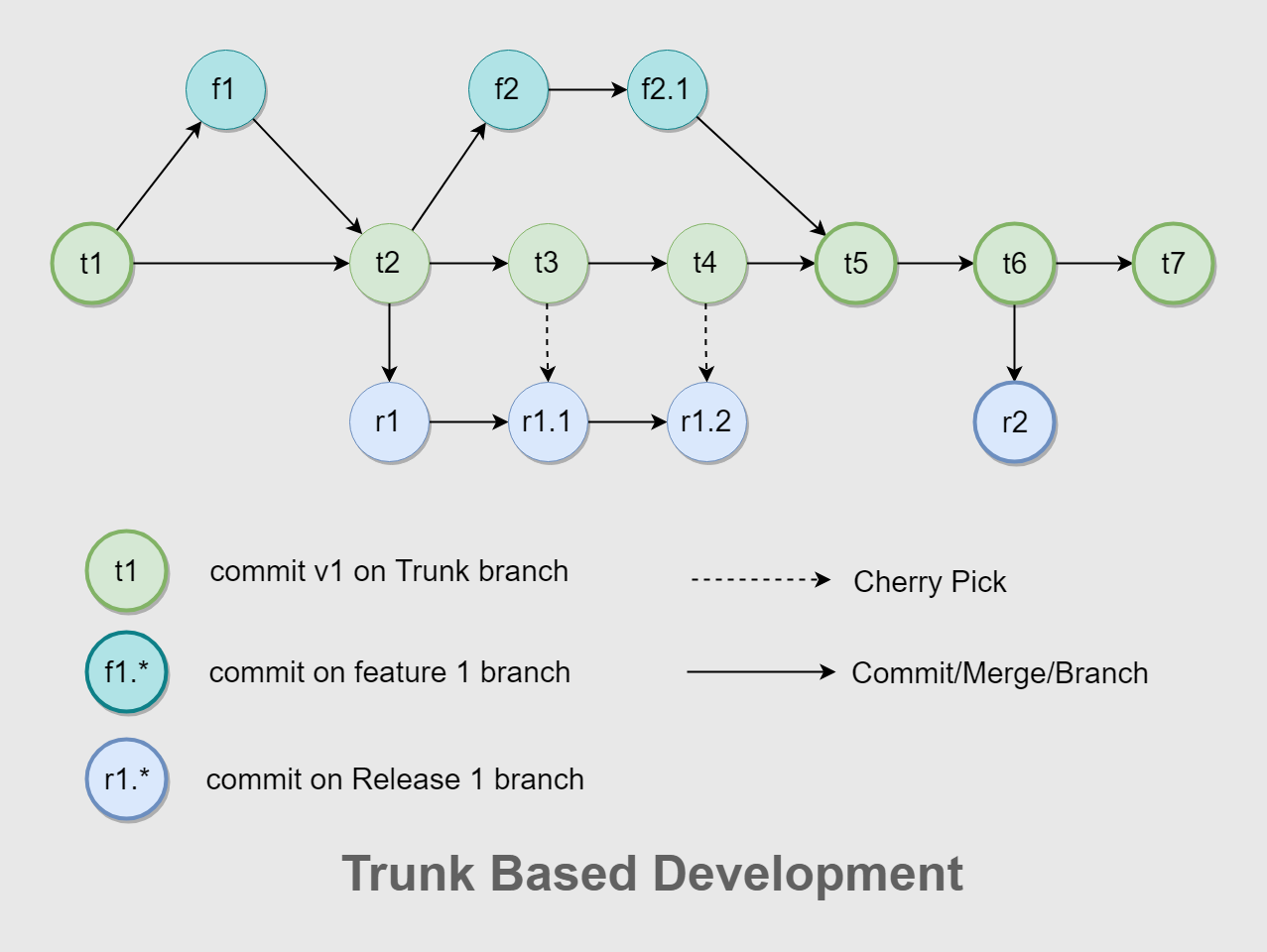

### Trunk-based

A.K.A.: Centralized

Only one long-living branch (trunk). Everyone commits directly to this branch (or to short-lived branches with frequent merges).

### GitFlow

In GitFlow, we have one main branch from which all releases are made, another long-living branch called `develop` that branches from the main one and back into it at the end of the sprint. We also have feature branches that live until the feature is completed, and hotfix branches that are for quick patches on production releases.

### Custom (per-team)

The most important thing when following a workflow style is to stay consistent and in agreement with the rest of the team. For example, here is the full workflow that we followed in our Cast project (as devised by Lev Chelyadinov):

1. In the beginning of the sprint, someone would create issues for every individual task, prefilled with acceptance criteria and milestones to a particular sprint

2. After the issues are created, they are assigned to the responsible person/people

3. If the assignment isn't satisfactory, issues are reassigned upon agreement of all involved parties

4. If the issue is of a low priority and assigned to no one, assign it to yourself before starting to work on it to let people know

5. Once you're done/when you want feedback, you create a PR, linking the issue with GitHub linking keywords.

6. At least one person should be assigned for review, preferably, randomly (configured using GitHub Actions)

7. Once the CI passes and the reviewer approves, the PR is merged (automatically) and the branch is deleted

## Best practices

Most importantly: follow your team's guidelines.

### Commit

- Keep your commits single-purpose

- Write meaningful (but concise) commit messages. Description can be added to the message's body

- Commit early and often in small instead of doing one mega-commit at the end of the day

- Do not commit generated files (executable binaries, build files, node_modules)

- Use imperative style

Keep the history linear as much as possible, and avoid rewriting it. Try to make it such that the commit history tells the story of the product's development.

For example, in a Pull Request (when reviewing), I like being able to go through the commits one by one and understanding as if the developer explained to me the whole process.

### Branching

- Don't push straight to master (I'm not a fan of trunk-based workflow) unless you're very early in the prototyping phase

- Add branch protection rules to require Pull Requests with approvals before merging to master

- Rebase your working branch on master so that you always work on updated code and keep the history linear

- Consider using interactive rebasing (if needed) to clean up your work before pushing (if needed)

### Hooks

Hooks are scripts that run locally when some git-related events happen.

Use `pre-commit` and `pre-push` to ensure the code follows your standards.

Example: scan for leaked API keys and do code formatting

## References

- [Pro Git Book](https://git-scm.com/book/en/v2)

- https://missing.csail.mit.edu/2020/version-control/

- https://xosh.org/explain-git-in-simple-words/

- https://bitbucket.org/product/version-control-software

- https://stackoverflow.com/questions/1408450/why-should-i-use-version-control

- https://www.quora.com/Why-is-Git-so-popular-for-version-control

- https://learngitbranching.js.org/

- https://docs.github.com/en

- https://www.atlassian.com/git/tutorials/comparing-workflows

- https://deepsource.io/blog/git-best-practices/

- https://git-scm.com/book/en/v2/Git-Branching-Rebasing

- https://git-scm.com/book/en/v2/Git-Tools-Rewriting-History