# SOLID Objects

## Introduction

SOLID is an acronym describing design principles for creating OOP systems. By committing your code to these principles you will naturally build systems that don't only work perfectly, but work elegantly.

## Learning Outcomes

1. Design methods and classes with exactly one responsibility

2. Design extension to classes to incorporate new behavior

3. Design proper realization and specialization relationships

4. Design purposeful abstractions and abstract methods

5. Design systems that interact through abstractions

---

Briefly, these five principles are:

- **Single Responsibility Principle** - Objects should have cohesive and complete responsibilities. It shouldn't be aware of knowledge it doesn't need and it shouldn't perform responsibilities that are irrelevant from it.

- **Open/Closed Principle** - Classes should be open to extension and closed to modification. Instead of changing the form and behavior of an existing class, you should extend the class

- **Liskov-Substitution Principle** - Substituting objects by their subtypes/realizations should always work.

- **Interface Segregation Principle** - A client shouldn't be forced to implement methods that it doesn't use

- **Dependency Inversion Principle** - Object relationships should depend on abstractions instead of implementations

### Single Responsibility Principle

#### The GOD Class

One of the canonical examples of violations against SRP is the concept known as the **god class**. A god class is a class that basically contains all the attributes and methods of the whole system. You'll recognize these god classes as those classes that control the behavior of objects (they contain the implementation of client objects' behavior). These god classes are also aware of all of the objects secrets (they expose and manipulate private attributes and methods).

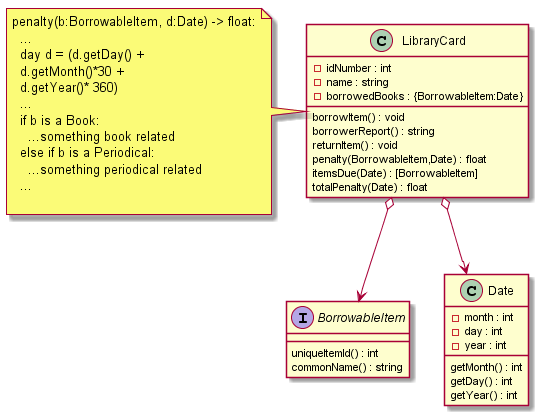

On the example above `LibraryCard` is a god class since it exposes the secrets of `Date` by forcing the creations of *evil* getters (`getMonth()`, `getDay()`, `getYear()`) for otherwise private details. Although it isn't obvious, it also tampers on the responsibilities of `BorrowableItem` by deciding by itself how penalty is calculated for each realization.

> The moment you ask an object what it's exact type is, you should consider refactoring your code since introspective checks like `isinstance` , `instanceof` `typeof` and etc., are symptoms of smelly design. You can think of these checks as analogies to racial discrimination since your client object asks the race (type) of the dependency.

#### Assigning the correct responsibilities

When you're introducing new behavior or information to a system, you should ask first: *who should be responsible of this behavior or information?*

- Who should be responsible of calculating the differences between dates? **`Date` should be responsible, not `LibraryCard`**.

- Who should be responsible of calculating the penalties of specific `BorrowableItem` realizations? **`BorrowableItem` realizations should be responsible, not `LibraryCard`**

The best implementation of the system contains multiple examples of SRP. The `Date` class should be responsible of subtracting dates and adding dates, not the `LibraryCard` class. Forcing `LibraryCard` to contain code for `Date` operations will force you into breaking the boundaries of your classes (e.g. creating getters to expose private attributes). `LibraryCard` should not be aware of **how** dates are subtracted to be able to subtract dates. The same is true for a `BorrowableItem`'s due date. The `LibraryCard` shouldn't contain the specifications as to how `BorrowableItem`s calculate their due date. In fact `LibraryCard` shouldn't even be aware of the exact type of the `BorrowableItem` (`isinstance` violates this).

The process of designing these cohesive systems requires not only OOP design techniques but also domain knowledge. The designer of the system, should know how a library system operates so that, he/she can accurately simulate their responsibilities on code.

You can also apply SRP on individual methods inside objects. Methods should be responsible of one thing only. Keeping methods pure like these will help reduce unwanted side effects. The builder/manipulator naming scheme will help you with this. Also a method should not be responsible of handling the problems. The method should delegate that responsibility to the clients of that method. The methods itself should only report the problem. The best way to do this in OOP is by raising an exception.

### Open/Closed Principle

A good class in OOP is both open and closed. It is open for extension but closed for modification.

To understand this principle lets have an example of a system that is closed for extension:

> Forgive the long Java-like method names, they're named as descriptive as possible so that I can s skip actually explaining what they do.

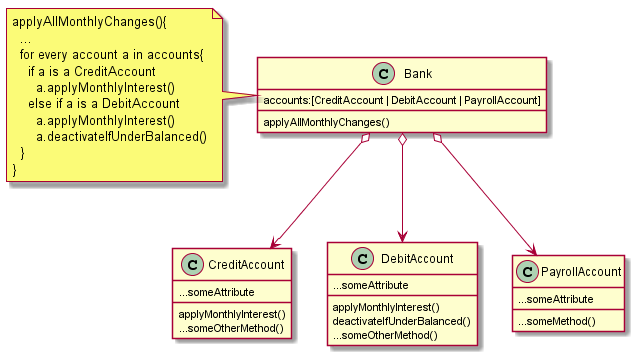

This is a system that indeed works perfectly. The bank will be able to apply the appropriate changes to the account types because of the `if-else` block that segregates the accounts based on its type (another instance of type discrimination so that's a hint that this is wrong). The problem with this is that whenever there are changes regarding the monthly changes or interest calculations, you would have to tamper with the contents of bank. This is **opening `Bank` up for modification**. Every time there's a change related to monthly updates you would have to do some kind of surgical procedure on `Bank` and rearrange its internal organs so that the change may be supported. This is extra rough on `Bank` because `Bank` shouldn't even be responsible for these behaviors (a violation of SRP). If there are new types of account, then you would have to open up `Bank` again and to add another `else if` block. Poor `Bank`, who knows how many more new types of accounts there are in the future.

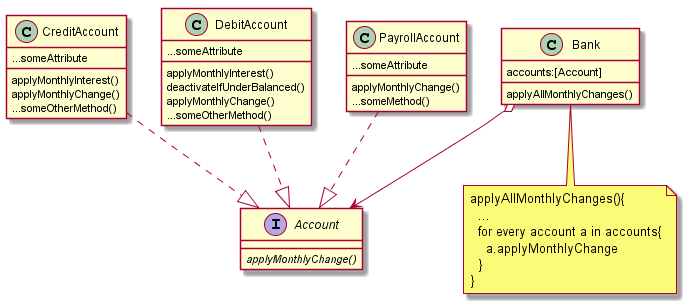

Instead of rearranging the organs of your classes to accommodate changes to behavior they are not even responsible for, you should close the classes for modification and open them for extension instead:

Since `applyMonthlyChange()` is an abstract method of account, all its realizations are required to implement it. We extend the functionality of `CreditAccount`, `DebitAccount`, and `PayrollAccount` by adding an extra method.

- inside `CreditAccount.applyMonthlyChange()` you just call `applyMonthlyInterest()`,

- inside `DebitAccount.applyMonthlyChange()` you call both `applyMontlyInterest()` and `deactivateIfUnderBalanced()`

- inside `PayrollAccount.applyMonthlyChange()` you do nothing

Is a method that does nothing inelegant? Not really because this is an accurate representation as to how a `PayrollAccount` changes every month— it doesn't. Also, in the future, the inertness of `PayrollAccount` may change so at least you have the function prepared.

> The previous library card example and bank examples are indeed similar . This is because introspective checks like `isinstance` are again symptoms of inelegant design.

Another example of this is how you need to augment the `PayrollAccount` class to contain the `recieveFund(float)` or `deposit(float)` method so that it can become a recipient for transfer.

> Closed for modification does not mean you cannot change literally anything in the class. Of course if there are mistakes in the specific behavior of the class then you have to modify it.

### Liskov-Substitution Principle

This principle basically dictates when should an object be a subtype or a realization of another object. Should `PayrollAccount` be a realization of `Account`? If you can substitute any instance of an `Account`with a `PayrollAccount` then the answer is yes. The same is true if you want to establish an inheritance relationship between `Account` and `PayrollAccount`. The LSP is important because it ensures the polymorphic capabilities of your realizations and subtypes.

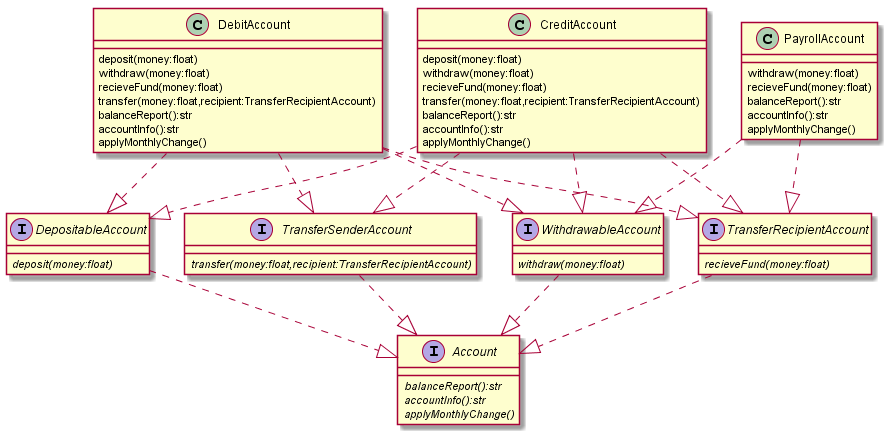

### Interface Segregation Principle

Sometimes the subtypes/realizations of a certain object may have diverse functionality. Some subtypes can deposit, some subtypes can't, all subtypes can be recipient for transfers but not all can be senders. The diversity of functionality supportability may sometimes force the designer to pollute the system with methods that the subtypes don't actually use. `PayrollAccount` will not use deposit but since it realizes `Account` then we reluctantly add it. This is a violation if LSP which states that an object should not be forced to implement methods it doesn't use.

#### Role Interfaces

The best way to design these diverse systems it by refactoring your architecture to have diverse role interfaces instead.

Now instead of cluttering you realizations with useless methods, your systems is now cluttered with role interfaces. This is a benevolent kind of clutter. Because more objects and looser dependencies make for a maintainable and therefore elegant system (in the same way a language with more words have less chances for ambiguity). Because of this clutter you can have rich polymorphism without sacrificing ISP. Although be careful not to over do it though. You wouldn't want a role interface for every conceivable method out there.

When you have role interfaces, you can refine lines of your code by describing which exact role interface applies. For example, instead if writing transfer to be an process which is `Account` to `Account` they are `TransferSenderAccount` to `TransferRecipientAccount`.

### Dependency Inversion Principle

The relationships between objects should be defined by surface instead of their interior. This means that How a bank interacts with an account should not be dependent on the implementation. The way `Bank` prints the balance report should not be by directly concatenating `"Your balance is" + account.balance` . Bank should interact with an account by printing the return value the abstract builder method, `balanceReport()`. The class `Bank` should not dissect an `Account` to retrieve the balance. It should tell the `Account` to build a balance report.

## Optional Reading

Bailey D., (2009) [SOLID Development Principles – In Motivational Pictures](https://lostechies.com/derickbailey/2009/02/11/solid-development-principles-in-motivational-pictures/). Accessed August 31, 2020