# Creational Patterns

## Introduction

Almost all programming languages with object oriented support provides you rich features in creating instances of classes using constructor methods. Inside the constructors you can add business logic to initialize objects and make them ready for use. Some programming languages (like Java or C++) even have the capability to have more than one constructor method so that instances can be shipped with different states depending on the chosen constructor.

Unfortunately native constructors capabilities are not powerful enough for our standards of elegance. Some systems have complicated object production mechanisms that require extra capabilities. Sometimes classes have too many attributes for a simple constructors. Sometimes object creation require polymorphic support and decoupling against the exact subtypes or realizations. Sometimes you need to ensure that certain classes have exactly one instance throughout the lifetime of your system.

## Learning Outcomes

1. Design systems that apply the factory method design pattern

2. Design systems that apply the abstract factory pattern

---

## Factory Method Pattern

### Problem

The exact type of the dependency (a product) created and used by some client (a factory) is decided by a client of that factory. Somewhere, inside this factory class, a specific product is being instantiated and maybe used (this instantiation happens maybe more than once). But, as it turns out, there are different types of products, (there's also the possibility of more product types in the future). You can change the code of the factory class to accommodate multiple product types. For every product, you modify the factory and add some if-else clause to produce the correct product type.

As you see this process is quite tedious. For every new product type that is added to your system, you perform surgery to the factory class. This process will end up forcing you to create smelly if-else checks to switch to the correct product type.

### Solution

You encapsulate the creation of a class inside a **factory method** that is specified to return an abstraction of the product. If there are other real product types that have to be produced, you create a specialized factory which overrides the factory method.

> Somewhere inside factory you have one or more instances of creating or using the product.

If you choose to build `Factory` as a concrete superclass, the factory method inside the `Factory` should return some realization of `Product`. This is the default product returned by any `Factory`. If you need to return a different `Product` realization, you override the factory method to return that particular `Product` realization.

### Example

#### Online Marketplace Delivery

Consider you're developing the product delivery side of an online marketplace app (think Amazon/Lazada). Your app is on its early stage so their is only one delivery option, standard nationwide delivery that takes a minimum of 7 days.

What you have is `Shipment` class that contains a `StandardDelivery` class. Inside the shipment class is the `shipmentDetails()` builder which builds a string representing the details of the shipment, this includes the delivery details (which requires access to the composed `StandardDelivery` instance). Inside the constructor of `Shipment` an instance of `StandardDelivery` is created so that every `Shipment` is set to be delivered using standard delivery.

This system does work. It works but it is still inelegant. As soon as your app grows, you will incorporate new delivery options like express delivery, or pickups or whatever. Every time you need to add a new delivery method you will need to perform surgery in `Shipment` since the `StandardDelivery` instance is created inside the constructor of `Shipment`. `Shipment`'s code is too coupled with `StandardDelivery`.

To solve this you need to implement the factory method pattern. Right now shipment is a factory since it constructs its own instance of `StandardDelivery`. To refactor this into elegant code, you need to so create an abstraction called`Delivery` first to support polymorphism. Inside `Shipment` instead of creating instances of `Delivery`'s using a constructor, you invoke a factory method that encapsulates the instantiation of `Delivery`. In this case we name this method `newDelivery()`. All it does is return an instance of `StandardDelivery` using its constructor.

In this new architecture, whenever there are new delivery methods a shipment could have, all you have to do is to create a realization of that delivery method. In this case the new delivery method is `ExpressDelivery` which delivers for two days but is twice as expensive. And instead of changing `Shipment` (violates Open/Closed Principle), you make an extension to `Shipment`. This extension is the specialization to shipment called `ExpressShipment` (a shipment that uses express delivery). In this specialization, you only need to override the factory method delivery, so that every instance of delivery construction creates `ExpressDelivery`. The difference between `ExpressDelivery` and `Delivery` is that `ExpressDelivery` has a delivery fee of 1000 and the estimated delivery date is 1 day after the processing date.

### Why this is elegant

- **Single Responsibility Principle** - the extra level of encapsulation on the construction of the product (factory method), allows the factory to be responsible of creating the exact product type it needs.

- **Open/Closed Principle** - instead of modifying the factory to incorporate the creation of different product realizations, you instead create an extension of the factory. No need for introspective checks since the factory method supports polymorphism of the product it creates.

- *Encapsulate what varies* - This pattern upholds one of OOP paradigms most important principles. Since the construction of product varies from product type to product type, it is encapsulated into the factory method.

- This avoids tight **coupling** between the factory and the product

> Coupled classes are classes which are very dependent on each other. Changing the code of one will most likely affect the other

### How to implement it:

1. Create an abstraction for all product types (`Product`).

2. Inside the base factory create the the factory method function `newProduct():Product`. Make sure it is specified to return abstraction `Product`.

3. For every new product type that is added to the system, create 2 new classes: the new product type as a realization of `Product` and, and the factory for the new product type as a specialization of `Factory`.

4. Inside each factory specialization override `newProduct()` to return the correct realization of `Product`.

5. Replace every instance of constructor calls inside `Factory` with a call to the factory method `newProduct()`.

## Abstract Factory

### Problem

Your system consists of a family of related products. These products also have different variants. Some client class or function dependent on your products needs a way to create these products so that the products match the the same variant. The exact variants of the family of products are decided during runtime somewhere else in the code (similar to product creation in a factory method). To accomplish this you can simply switch between products using some kind of selection (if-else, switch-case, when, etc.)

This solution works right now, but what if there are new product variants? Every time there are new variants you will end up adding new branches to your client code.

### Solution

You create different kinds of factories that realize under the same abstract factory. Said abstract factory will contain abstract factory methods that delegate product construction for each product type. These factory methods are named `newProductA()` and `newProductB()`.

For every possible variant, you create a realization if `AbstractFactory`. The exact realization of factory (`FactoryVariant1` or `FactoryVariant2`) will decide the variant of the family of products that are created. These realizations will implement the factory methods based on their variant. For example `FactoryVariant1`'s `newProductA()` will return a new instance of `ProductAVariant1`, while `FactoryVariant2`'s `newProductA()` will return a new instance of `ProductAVariant2`. Using this an instance of `AbstractFactory` can either produce products from variant 1 or variant 2 depending on its exact realization.

Whenever there are new variant types that are added to your system, you will not need to change any client code. All you need to do is to create new `Product` realizations based on the new variant as well new `AbstractFactory` realizations that produce these product variants.

### Example

#### Bootleg Text-based Zelda Game

You're creating the dungeon encounter mechanics of some bootleg text-based zelda game. In this game, every time you enter a dungeon, you encounter 0-8 monsters (the exact number is randomly determined). There are 3 types of monsters, bokoblins, moblins, and lizalfos (different types have different moves). The exact type of monster is randomly decided as well.

Right now the game works like this:

As soon as you enter the dungeon, all the enemies are announced:

```

5 monsters appeared

A lizalflos appeared

A lizalflos appeared

A lizalflos appeared

A moblin appeared

A moblin appeared

```

After this, each enemy in the encounter attacks. They randomly pick an attack from their moveset.

```

Lizalflos thorws its lizal boomerang at you for 2 damage

Lizalflos thorws its lizal boomerang at you for 2 damage

Lizalflos camouflages itself

Moblin stabs you with a spear for 3 damage

Moblin stabs you with a spear for 3 damage

```

The encounter ends with Link dying since you haven't coded anything past this part.

You decide to make things exciting for your game by adding harder dungeons, medium dungeon and hard dungeon.

##### Medium dungeon

Instead of encountering, normal monsters you encounter stronger versions of the monsters, these monsters are blue colored:

- **Blue Bokoblin**

- equipped with a spiked boko club and a spiked boko shield

- bludgeon deals 2 damage

- **Blue Moblin**

- equipped with rusty halberd

- stab deals 5 damage

- kick deals 2 damage

- **Blue Lizalflos**

- equipped with a forked boomerang

- throw boomerang deals 3 damage

##### Hard dungeon

These monsters are silver colored extra stronger versions of the monsters

- **Silver Bokoblin**

- equipped with a dragonbone boko club and a dragonbone boko shield

- bludgeon deals 5 damage

- **Silver Moblin**

- equipped with knight's halberd

- stab deals 10 damage

- kick deals 3 damage

- **Silver Lizalflos**

- equipped with a tri-boomerang

- throw boomerang deals 7 damage

To seamlessly incorporate these harder monsters in your system, you need to create an abstract factory for each dungeon difficulty. There are now three variants for each monster. For every variant, there is a factory that spawns new instances of each monster.

### Why this is elegant

- **Open/Closed Principle** - This solution is easier to maintain since you can add more variants of `Product` without touching any existing code. All you have to do is to add new realization for `Product` and a new realization `AbstractFactory`

- Changing the form and behavior of specific variants are isolated since its creation is abstracted.

- You can easily switch between variants by swapping out the factory.

### How to implement it:

- For every product in the family of products, create an abstraction of it (`ProductA`, `ProductB`).

- For every variant of the products, create a factory, (`FactoryVariant1`, `FactoryVariant2`). These factories must realize under an abstraction `AbstractFactory`. The factory should contain abstract factory methods for each product,

- Inside every factory realization implement all factory methods.

## Singleton Pattern (Optional Read)

### Problem

Sometimes it wouldn't make sense for a class to have more than one instance in the lifetime of the application. These things are called singletons.

### Solution

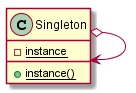

Inside the singleton. Create a static attribute that represents the singleton. Since it is static all instances of the class will share this value. Create a builder to lazily instantiate the value of the singleton and expose the value of the instance.

Disallow the usage of the normal constructor as much as possible. To access the shared static instance, use the builder.

> Disallowing the creation of a singleton depends on the language you use, you can set the constructor to private, or you can raise an error if you try to use the constructor outside the instance builder.

>

> You can also choose to not disallow the use of the constructor, as long as you trust the users to always use the instance builder instead.

### Example

#### A Catalog of Globals

It doesn't make sense for you to keep multiple copies of global variables in your application, so you decide to place them in a singleton class.

#### Why this is NOT elegant

A singleton pattern is actually hated by most developers. Yes you can ensure that there is exactly one instance of a class, but its advantages come with a lot of drawbacks.

- You can ensure single instance classes, just by being vigilant.

- Singletons require the use of static attributes and methods. Statics are anti-pattern because they are global variables and manipulators that can have invisible changes to state.

- Singletons are usually symptoms of bad design.

## Optional Reading

Shvets A. (2018) [Creational Patterns](https://sourcemaking.com/design_patterns/creational_patterns) Accessed August 31, 2020