# Behavioral Patterns

## Introduction

Some systems require complex and extremely decoupled relationships. Behavioral patterns are used on these tightly interconnected systems so that they are easier to maintain. These patterns separate behavioral responsibilities among the classes in your system in such a way that volatile behaviors are encapsulated deep into your object structure.

## Learning Outcomes

1. Design systems that apply the strategy pattern

2. Design systems that apply the state pattern

3. Design systems that apply the command pattern

4. Design systems that apply the observer pattern

5. Design systems that apply the template pattern

6. Design systems that apply the iterator pattern

---

## Strategy pattern

### Problem

Some systems require behavior that have to be parametrized for other behavior. This is easily done in a functional programming environment since higher order functions are used to represent these. In programming languages that don't support these features, the strategy pattern is used.

### Solution

Functions that are not first class citizens are encapsulated inside a `Strategy` class. A strategy class simply contains the method `execute(params)`, which represents the behavior that should be passed into a higher order function. Any method that can be passed into the higher order function should realize `Strategy`.

The object `params` represent the data that you need to pass into the correct class. In this pattern you pass the the whole `Strategy` realization so that `strategy.execute(params)` perform the desired behavior. You can add other methods in the `Strategy` abstraction, if it makes sense for the system.

### Example

#### Fraction Calculations

You're creating a less sophisticated version of a fraction calculator. This calculator only has arithmetic operations inside it, addition, subtraction, division, and multiplication. Inside this calculator, a calculation is represented in a `Calculation` instance. Every calculation has four parts:

- `left` - represents the left operand fraction

- `right` - represents the right operand fraction

- `operation` - represents the operation ($+$,$-$,$\times$,$\div$)

- `answer` - represents the solution of the operation

Kotlin does indeed support higher order functions but your boss is anti-functional programming so they forbid the use these features. Because of this you decide to implement the strategy pattern.

To do this, you need to create an abstraction called `Operation` to represent the different operations. For each operation, you create a class that realizes `Operation`.

### Why this is elegant

- **Open/Closed Principle** - If you want to add new strategies, you wouldn't need to touch any existing code.

- The implementation of a strategy is deeply tucked inside multiple layers of encapsulation. Changing these implementations are very easy.

- You can swap strategies during runtime in the same way you do in functional programming.

### How to implement it

1. Create an abstract `Strategy` that contains an abstract method called `execute`. This method should be specified to accept all the necessary parameters needed by your parameterized function.

2. For every strategy, the higher order method can accept, you create a realization for `Strategy` and implement the correct behavior in `execute`.

3. The higher order function should now be specified to accept a `strategy` of type `Strategy`.

4. Inside the higher order function, whenever it wants to perform the strategies embedded behavior, call `strategy.execute(...)`.

## State Pattern

### Problem

Some objects can change into many different states. If different objects behavior is dependent on its current state, it would require, bulky and annoying if-else blocks to handle its dynamic behavior.

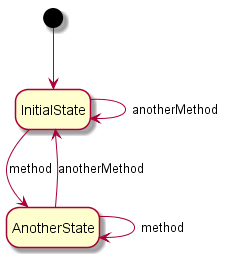

### Solution

An object that can have many states should contain an attribute representing its state. Instead of performing, state dependent behavior directly inside the object, you delegate this responsibility to its embedded state instead. In this way the object will behave according to its current state.

The state may be required to contain backreference to the context object that owns it. This is only required if state methods requires to access/control the context that owns it.

### Example

#### States of matter

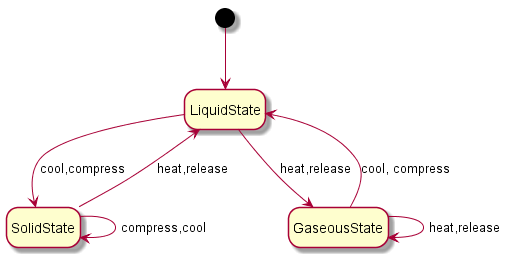

The state of any given matter is dependent on the pressure and temperature of its environment. If you heat up some liquid enough it will turn to gas, if you compress it enough it will become solid.

The state diagram would look something like this:

To implement something like this, you would need to create matter which owns an attribute called `state` which represents the matter's current state. Since there are three states, you create three realizations to a common abstraction to state.

When you compress/release/cool/heat the matter, you delegate the appropriate behavior and state change inside `state`'s version of that behavior. Each `State` realization will need a backreference to the `Matter` that owns it. This backreference will allow the `State` instance to change the `Matter`instance that owns said `State` intance.

> Delegating behavior to the composed state means that, when the `Matter` instances invoke, `compress()`, `release()` `heat()`, and `cool()`, the composed `State` owned by the matter calls its own version of `compress()`, `relaease()` `heat()`, and `cool()`.

> Matter owns an instance of `State`, and that instance has an attribute called `matter`. The attribute `matter` is the reference to the instance of `Matter` that owns it. The `State` instance needs this reference so that it can change the matter's state when it is compressed, released, heated, or cooled.

### Why this is elegant

- **Single Responsibility Principle** - behavior related to state is delegated to the state itself.

- **Open/Closed Principle** - You can incorporate new states to the system without touching any existing client code

- Implementing this pattern will remove bulky and annoying state conditionals

### How to implement it

1. Create an abstract `State` that contains abstract methods for all state dependent behavior (context related behaviors that are dependent on context's state).

2. For every state the `Context` can have, create a realization of `State`.

3. `Context` owns an attribute that represents the current state (`currentState`) that it owns.

4. If the state needs to control the `Context` instance that owns it, add a backreference to `Context` inside state.

5. Whenever a `Context` instance performs state dependent methods, it calls `currentState.stateDependentBehavior()` instead so that its behavior is dependent on its current state.

## Command Pattern

### Problem

Sometimes, object behavior contain complicated constraints. Sometimes, the system require the behavior to be invoked by an object but performed by another (this is common in presentation layer/domain layer separation in MVC enterprise systems). Sometimes, the system requires behavior to be undone. Sometimes the system requires a history of the behaviors that were being performed.

### Solution

These problems have a common solution, the **command pattern**. A `Command` is a more powerful version of a `Strategy`. While both of them encapsulates behavior, a `Strategy` is just that, a function wrapper. A `Command` on the other hand contains which object performs the behavior, which parameters are needed to perform the behavior, and how to undo the command (if needed).

Creating `Command`s, allow for more flexible behavior responsibility assignments. A separate `Invoker` object triggers the behavior by creating a command. This `Invoker` prepares the command with the appropriate `Reciever` (the object performing the command), and the appropriate parameters. The invoker then executes the prepared command. The command doesn't actually do anything, it just tells the `Reciever` to call the appropriate method.

This separation of responsibility allows for the creation of extra features that may be required for your system:

- If you want to keep a history of the performed commands, the `Invoker` may keep a list of `Commands`. This way the data stored in the list history, is a perfect representation of the previous commands.

- If you want the `Commands` to be undoable, you can store a backup of the receiver (and other affected objects) by the `Command` inside each instance of `Command` . Undoing a command will be as simple as restoring the receiver to its backup.

> Instead of passing the receiver in the `Invoker` methods, you can create an attribute called receiver inside `Invoker`. But doing this will make it so there is one `Receiver` instance for every `Invoker` instance.

>

> The commands should only affect the receiver. If the behavior that is performed changes a lot of objects, then make a `Receiver` class that encapsulates all of the affected objects. Doing this will make the implementation of undo easier since the backup inside of the command will simply be an older version of `Receiver`.

>

> Different command realizations are not necessarily of the same `Strategy`. That's why the parameters of the behavior are stored as attributes of the command, not passed in the `execute()` function. This is so that no matter what the command is, all `execute()` functions will have the same type signatures.

### Example

#### Zooming through a maze

You're creating a maze navigation game thing. This is what the application currently has right now:

- `Board` - this represents the layout of the maze. The layout is loaded from a file. It has these attributes:

- `__isSolid` - this is a 2 dimensional grid encoded as a nested list of booleans which represents the solid boundaries of the maze. For example if `__isSolid[row][col]` is true then it means that that cell on (row,col) is a boundary

- `__start` - a tuple of two integers that represent where the character starts

- `__end` - tuple of two integers that represent the position of the end of the maze

- `__cLoc` - tuple of two integers that represents the current location of the character

- `moveUp()`, `moveDown()`, `moveLeft()`, `moveRight()` - moves the character one space, in the respective direction. The character cannot move to a boundary cell, it will raise an error instead.

- `canMoveUp()`, `canMoveDown()`, `canMoveLeft()`, `canMoveRight()` - returns true if the cell in the respective direction is not solid.

- `__str()__` string representation of the board. It shows which are the boundaries and the character location

What's missing right now is controller support. This is how a player controls the character on the maze:

- `dpad_up()`, `dpad_down()`, `dpad_left()`, `dpad_right()` - The character dashes through the maze in the specified direction until it hits a boundary.

- `a_button()` - The character undoes the previous action it did.

To implement controller support you need to create a `Command` abstraction which is realized by all controller commands. The `Controller` (which represents the controller) is the invoker for the commands. Since commands are undoable, this controller needs to keep a command history, represented as a list. Every time a controller button is pressed, it creates the appropriate `Command`, executes it and appends it to the command history. Every time the `a_button()` is pressed to undo, the controller pops the last command from the command history and undoes it.

### Why this is elegant

- **Single Responsibility Principle** - The behavioral responsibilities in the system are thoroughly separated. One invokes the command, and the other performs the behavior associated with the command.

- **Open/Closed Principle** - If there are more commands you want to add, you don't have to touch any existing code.

- Switching between invokers and receivers is easily done

- You can implement undo (and redo)

- You can defer the execution of behavior

- A command may be made of smaller simpler commands

### How to implement it

1. Create an abstraction `Command` that contains abstract method `execute()`, and other command related methods like `undo()`.

2. For every command, create a realization to `Command`. These commands uses a reference to a `Reciever` instance. This instance represents the instance/s that are affected whenever `Command` realizations are executed.

3. Create an `Invoker` class that will be responsible for instantiating, preparing, and executing commands. Inside these class are methods for invoking each commands. When these methods are called, the invoker does the following:

1. Instantiate an instance of `Command` called `c` with the correct realization.

2. select the receiver of the `Command`, including the related parameters.

3. invoke `c.execute()`.

4. If the system supports undoable commands, the `Invoker` should keep a list of commands called `commandHistory` and each command instance should keep a reference called `backup` to enable restoration of `Reciever` instances.

## Observer Pattern

### Problem

What if you need to inform a lot of objects about the changes to some interesting data? If you globalize the data and let your client objects poll for changes all the time, this will affect the security and safety of your interesting data. Plus, global data is something that should be avoided as much as possible. Also, forcing your objects to poll for changes all the time will be inefficient if your interesting data has not changed.

### Solution

The responsibility of sharing information about the changes to interesting data should not be placed in the clients of the data. You should create a notifier class that encapsulates the interesting data. This class should be responsible of notifying interested clients about changes on the subject.

To do this you need to encapsulate the interesting data (from now on lets call it the `subject`), into a `Publisher` class. An instance of this class will be responsible of notifying the observers for any change in the `subject`. Whenever there are changes to the subject, the `Publisher` instance calls `notifyObservers()` so that all interested observers will be informed of the change. Any class that is potentially interested in the `subject` should realize an `Observer` abstraction, which in the bare minimum contains, the `update(updatedSubject)` function. Inside `Publisher`'s `notifyObservers()` method, every subscriber (an interested observer) is updated (`subscriber.update()`).

Any instance of an `Observer` should be subscribed to the change notifications using `Publisher`'s `subscribe()` function. They can also be unsubscribed using the`unsubscribe()` function.

> Whenever an observer has updated, the publisher needs to pass all the necessary details in the notification. This is generally done by passing the updated subject in the `update(updatedSubject)` method.

>

> In some cases, the observer needs to keep a copy of the subject as an attribute. Make sure to change the value of this attribute during updates.

>

> Make sure that changes to the subject are only done using the `Publisher` class (`manipulateSubject()`). If you change the subject without using `Publisher`'s methods, your subscribers won't be notified.

### Example

#### Push Notifier for Weather and Headlines

You are creating a push notification system that works for multiple platforms. You want to distribute information about the current weather and news headlines. This system will be potentially used on many platforms so you have to think about the maintainability issues for adding new platform support.

To implement this, you have to apply the observer pattern. Your subject would be `Weather` data and `Headline` data (which are their own classes). These subjects should be encapsulated into a single publisher class (which will be called `PushNotifier`).

Any platform, that is interested in the changes to the subject should realize a `Subscriber` abstraction (Observer), which contains the abstract method update().

You need to implement th following observer realizations:

- `EmailSubscriber` - every time the `currentWeather` or `currentHeadline` changes you send an email to the specified `email`. (you don't have to actually send an email. You can just simulate sending an email by printing something like "sending <weather> and <headline> to <email>").

- `FileLogger` - every time the `currentWeather` or `currentHeadline` changes, you append the updated weather and headline to the file specified in the attribute `filename`. You actually have to update a file via kotlin/python file writing.

### Why this is elegant

- **Open/Closed Principle** - You can add new `Observer` realizations seamlessly every time there are new objects that are interested in the subject.

- A observer can be subscribed/unsubscribed during runtime

### How to implement it

1. Create an `Observer` abstraction that represents all classes that can potentially observe changes to the `Publisher`. `Observer` will contain the abstract method `update()`.

2. All classes that want to be notified about changes to the `subject` should realize `Observer`.

3. `Publisher` will either own/use an instance of the `subject` of interest. It will also use an attribute which is stores the list of `Observers` that are interested in the subject. To attach or detach `Observer`s, `Publisher` contains the methods `subscribe()` and `unsubscribe()`.

4. Every time `subject` is manipulated, it should be done through `Publisher` , because `Publisher` needs to notify all `Observers` in its observer list attribute after every manipulation. This notification is done through `notifyObservers()` after the end of every subject manipulation.

5. Inside the `Publisher`s `notifyObservers` method, every `Observer` in its list of observers invoke their `update()` method.

## Template Method Pattern

### Problem

Say you have two or more *almost* identical behaviors from different classes. Rewriting these object behaviors as separate methods for each class duplicates many parts of the code (especially if the behavior has a lot of lines of code).

### Solution

To avoid code duplication, you break down your code into individual steps. By doing this you can create a superclass that contains the implementation for all common steps. This superclass will also contain the common implementation for the **template method**, the method that combines all steps into the original object behavior. Differences between steps will be resolved under different specializations of this superclass.

The method `templateMethod()` calls each of the steps defined in `step1()`, `step2()`, `step3()` and `step4()`. The exact type of the instance (either `Specialization1` or `Specialization2`) decides which versions of the steps are executed. For example, if the exact instance of the class is a `Specialization1`, it performs the template method with special versions of `step1()` and `step4()` (since `Specialization1` overrides them) but the other parts are inherited from the `Template`.

> The steps in the superclass can be a mix of abstract methods and concrete methods. Make a method abstract if you want to force all specializations to override these steps. You'll want to do these if some of the steps in your template doesn't have a default implementation.

### Example

#### Brute Force Recipe

If you write brute force algorithms as search problems, they will have a common recipe. This is the reason why it is called the exhaustive search algorithm. It will traverse all of the elements in the search space, trying to check the validity of each element, until it completes the solution

**Equality Search**

Search for integers equal to the target

```python

#searchSpace = [2,3,1,0,6,2,4]

#target = 2

i = 0

solutions = []

candidate = searchSpace[0]

while(i<len(searchSpace)):

if candidate == target:

solutions.add(candidate)

candidate = searchSpace[++i]

#solution = [2,2]

```

**Divisibility Search**

Search for integers divisible by the target

```python

#searchSpace = [2,3,1,0,6,2,4]

#target = 2

i = 0

solutions = []

candidate = searchSpace[0]

while(i<len(searchSpace)):

if candidate % target == 0:

solution.add(candidate)

candidate = searchSpace[++i]

#solution = [2,0,6,2,4]

```

**Minimum Search**

No target, searches for the smallest integer

```python

#searchSpace = [2,3,1,0,6,2,4]

#target = None

i = 1

solutions = [searchSpace[0]]

candidate = searchSpace[1]

while(i<len(searchSpace)):

if candidate <= solutions[0]

solutions[0] = candidate

candidate = searchSpace[++i]

#solution = [0]

```

**Common Recipe**

```python

i = 0

solutions = []

candidate = first()

while(isStillSearching()):

if valid(candidate):

updateSolution(candidate)

candidate = next()

```

Because of this we can write a general brute force template method that would return the solution to brute force problems. To do this you create a superclass `SearchAlgorithm()` that contains the template method for brute force algorithms. If you want to customize this algorithm for special problems, all you have to do is to inherit from `SearchAlgorithm` and override only the necessary steps.

> is `isValid()` and `updateSolution(candidate)` is different for each algorithm so it doesn't have a default implementation. It would be best to make these steps abstract.

### Why this is elegant

- **Open/Closed Principle** - The `Template` is open for extension but closed for modification

- *Encapsulate what varies* - steps can vary from specialization to specialization, therefore they are encapsulated into step methods.

- Implementing this pattern will remove duplicate code in the common parts of the algorithm.

- Clients may override only certain steps in a large algorithm, making it easier to create specializations

### How to implement it

1. Create an abstract class called `Template`. It contains the method `templateMethod()` broken down into separate steps through separate `step1()`, `step2()`, ... and etc. methods. When invoked `templateMethod()` will just call these step methods.

2. Each step method inside `Template` will contain the default implementation of that step. If there is no default implementation, the method should be abstract.

3. For every similar behavior to `templateMethod()` a specialization of `Template` is created. These methods will implement all abstract methods and override all step methods that vary for its behavior.

## Iterator

### Problem

One of the most common iteration recipes that you'll likely implement is the **for-each** loop. This loop traverses a collection, and performing some kind of operation along the way. Most programming languages implement for each loops on built in collections like arrays, sets, and trees. But what about non-built in collections?

### Solution

For non built-in collections, you can create an iterator that does the traversal for you. On the bare minimum these iterators will realize some `Iterator` abstraction that contains the methods, `next()`, and `hasNext()`. From these methods alone you can easily perform complete traversals without knowing the exact type of the collection:

```python

i = collection.newIterator()

while i.hasNext():

print(i.next())

```

The `hasNext()` method, returns a boolean value that indicates whether or not there are more elements to be traversed. The `next()` method, returns the next element in the traversal.

A collection can have more than one `Iterator`s, if it makes sense for the collection to be travsersed in more than one way. Despite this possibility, a collection must have a default iterator which will be the type of the new instance returned in the factory method, `newIterator()`

### Why this is elegant

- **Single Responsibility Principle** - Traversal algorithms can now be placed into separate classes that interact with an iterator instead of the collection itself.

- **Open/Closed Principle** - You can implement new types of collections and iterators without touching any existing code.

- You can traverse all the elements in a collection, even if you don't know the exact type of the said collection.

- Two iterators, can iterate over the same collection without problem as long as the iterators are of different instances.

### How to implement it

1. Create an abstraction called `Iterator` which contains the abstract methods `next()` and `hasNext()`.

2. Create an abstraction called `Collection` which contains the abstract method `newIterator()`.

3. For very collection that can be iterated through create a realization to `Collection`. Inside these `Collection` realizations, the `newIterator()` method must be implemented which simply returns a new instance of the default `Iterator`. (for collections that can be iterated through in more than one way, create different methods for creating other iterators as well but always keep `newIterator()` as the one that returns a new instance of the default iteration).

4. For every different way of iterating through a `Collection` realization, a realization to `Iterator` must be created as well.

5. `Iterator` realizations should contain an attribute that refers to the collection instance it is iterating through.

## Optional Reading

Shvets A. (2018) [Behavioral Patterns](https://sourcemaking.com/design_patterns/behavioral_patterns) Accessed August 31, 2020