# Structural Patterns

## Introduction

As your system evolves, the structure of your classes could get complicated. As you introduce more features, your classes become bigger and harder to maintain. To alleviate these issues, you can assemble objects into maintainable structural patterns.

## Learning Objectives

1. Design systems that apply the decorator pattern

2. Design systems that apply the adapter pattern

## Decorator Pattern

### Problem

Some of your classes require extra features that can be added and removed during runtime. Sometimes you even need to support a set of extra features that can be arbitrarily combined with each other. You need to do this without breaking how these classes are being used by their clients.

### Solution

To solve this issue, all you have to do is to apply the open/closed principle. For every feature that can be arbitrarily added to some a simple class, you need to create a `Decorator` that extends the features of classes using inheritance and composition at the same time. The neat thing about this pattern is that the `Decorator`s will have polymorphically the same type as the simple class due to inheritance. `Decorator`s will also be able to control instances of the simple class because of composition.

To create an instance of a `SimpleClass` decorated by `Decorator1`, all you need to do is to wrap the `SimpleClass` instance with an instance of `Decorator1`. When this `Decorator1` instance, calls `doSomething()` it calls the wrapped `SimpleClass ` instance's `doSomething()` and do some extra behavior.

```kotlin

//Decorator1's implementation of doSomething():

override fun doSomething() {

wrappedObject.doSomething()

doSomethingExtra()

}

```

It would be handy to create a `BaseDecorator` abstract class that is inherited by all decorators. It's not required but this class will form a class hierarchy for all decorators. Plus, you can write all of the common behavior and data into this class. It would be better for the `BaseDecorator`'s `doSomething()` method to be abstract so that the decorator realizations are forced to override `doSomething()`.

### Example

#### Decorating Sentences

A sentence can be defined as a list of words (words are strings). The string representation of a sentence is the concatenation of all of the words in the list, separated by a space.

Instances of sentences can be printed with formatting:

- **bordered** - Given the sentence, `["hey","there"]` it prints:

```

-----------

|hey there|

-----------

```

- **fancy** - Given the sentence, `["hey","there"]` it prints:

```

-+hey there+-

```

- **uppercase** - Given the sentence, `["hey","there"]` it prints:

```

HEY THERE

```

The formatting of a sentence is decided during runtime. These formats should also allow for combinations with other formats:

- **bordered fancy** - Given the sentence, `["hey","there"]` it prints:

```

---------------

|-+hey there+-|

---------------

```

- **fancy uppercase** - Given the sentence, `["hey","there"]` it prints:

```

-+HEY THERE+-

```

To accomplish these features, you need to implement the decorator pattern. Each formatting will be a decorator for `Sentence` objects. These formats need to inherit from some abstract `FormattedSentence` class. This abstract class is specified to compose and inherit from sentence. The behavior that needs to be decorated is the `__str__()` function since you need to change how sentence is printed for every format.

### Why this is elegant

- **Open/Closed Principle** - Decorators extend classes via inheritance. It is easier to add new decorators without touching any exiting code.

- A class can have many variants because of diverse combinations of behaviors can be cleanly implemented using this pattern.

- You can arbitrarily mix and match decorators without the worry of polymorphic incompatibility during runtime

### How to implement it

1. Create an abstract class `BaseDecorator` that specializes some `SimpleClass`. This `BaseDecorator` will also have the attribute `wrappedObject` which is a reference to an instance of the decorated `SimpleClass`. This attribute is set as protected so that it may be inherited by `BaseDecorator`s specializations. `BaseDecorator` also contains the abstract method `doSomething()`. This method's behavior, when invoked by `BaseDecorator`s specializations, changes depending on the decorations attached to `SimpleClass`

2. For every decoration, that can decorate `SimpleClass`, a specialization for `BaseClass` is created. These specializations implement `doSomething()` in a manner that augments/modifies `SimpleClass`'s own `doSomething()`

## Adapter Pattern

### Problem

As the system evolves, you'll likely encounter interfaces of instances that are incompatible with their intended clients. These interfaces do perform the necessary behavior, but maybe the method names are just different. This happens quite a lot since the interface of the dependency may be originally built for different reasons. The interface may be an external module imported on existing client code. You can just change the incompatible interface to support the functionality you need but this is not always possible and may introduce code duplication.

### Solution

In the same way vga is usable on an hdmi port using an adapter, you can use an incompatible dependency on a client as a compatible instance using the adapter pattern.

Say you have an instance of `AbstractDependency` (it could be any realization of `AbstractDependency`), that needs to be used like an instance of `RequiredInterface` by some client. In this example, the `RequiredInterface`'s `method()` works the same way as `AbstractDependency`'s `dependencyMethod()`. But unfortunately they have different names, thus creating the incompatibility.

You can rename `dependencyMethod()` into `method()` and change `RealDependency`'s abstraction from `AbstractDependency` to `RequiredInterface`. This will fix the incompatibility but it will break existing clients of `AbstractDependency` since the method names have been changed. To avoid breaking clients of `RealDependency` you instead make it so that `RealDependency` realizes both `AbstractDependency` and `RequiredInterface`. This will fix the incompatibility without affecting any client code but this introduces redundant code and violates the Interface Segregation Principle. If `RealDependency` has specializations, it will clutter its specializations with redundant code as well.

What you need to do is to create an adapter to `AbstractDependency` called `Adapter` which realizes `RequiredInterface`. To adapt the instance of `AbstractDependency`, you have to compose it inside the `Adapter`. This way `dependencyMethod()` is now adapted to `requiredMethod()`.

Whenever, an instance of `Adapter` calls `requiredMethod()` it instead delegates the behavior to the embedded `dependency`, which instead calls `dependencyMethod()`

### Example

#### Printable Shipments

Looking back at our previous lab exercises, some of the example classes contain string representation but do not implement the `toString()` function. An example of this is `Shipment` back from the factory method example. It does contain a string representation builder called `shipmentDetails()`, but printing a shipment is quite tedious since you have to print, `s.shipmentDetails()`. You can replace the name of `shipmentDetails()` to `toString()` but this will potentially affect other clients of shipment. You can add the `toString()` function which does exactly the same but this may introduce unwanted code duplication.

The best solution for this problem is to create an adapter for shipment called `PrintableShipment`. This adapter will realize some `Printable` abstraction, which only contains the abstract method `toString()`.

### Why this is elegant

- **Open/Closed Principle** - Instead of changing existing incompatible interfaces, you can extend them by creating adapters.

- **Interface Segregation Principle** - Instead of cluttering up your code with duplicate functions and unused interface methods, you instead create adapters only when it is needed.

### How to implement it

1. If you want an `AbstractService` to be used like a `RequiredInterface`, Create a `ServiceAdapter` that realizes `RequiredInterface` and contains an attribute `service` that is a reference to an instance of `AbstractService`.

2. Inside `ServiceAdapter`, the implementations of `RequiredInterface`'s abstract methods are merely calls to the methods of the reference `service`.

## Composite (Optional Read)

### Problem

When entities in your system needs to be represented like trees, then you represent them like trees.

### Solution

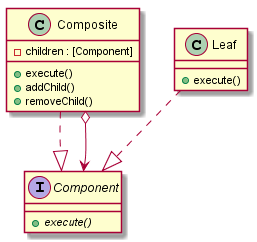

The composite pattern describes a tree structure described polymorphically. A tree node can either be a general tree or a leaf. in the composite pattern, a `Component` (tree node) can either be `Composites` (general tree), or a `Leaf`. Leaves and Composites are realizations of `Component`.

### Example

#### File System

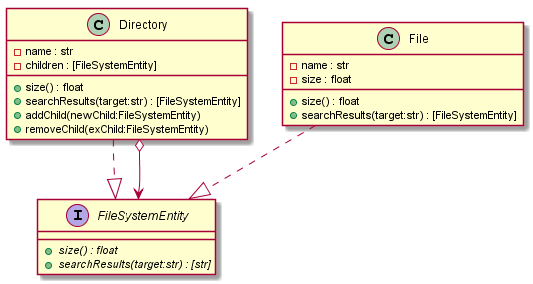

The file system in your computers are described using a tree structure. The entities in your file system are either directories or files.

What you need to do is to implement a simulation of a file system. Each node of the file system should be able to call the following methods:

- **`size()`** - the size of a `File` is based on the attribute size which is set during the initialization of the `File` instance. The size of a `Directory` is the size of all the `FileSystemEntities` inside it.

- **`searchResults(target)`** - if used by a `File`, if the name of the file matches the `target` it returns a list containing the `File`, if not it returns an empty list. If used by a `Directory` returns a list containing all the of the instances of `FileSystemEntity` (including itself) that matches the target inside the `Directory`.

### Why this is elegant

- **Open/Closed Principle** - You can introduce new component realizations in the system without touching any existing code.

- Working with composite trees are easier because of the polymorphism in the pattern

### How to implement it

1. Create an abstraction called `Component` that contains the abstract methods that are supposed to be executed across all components.

2. The `Component` has two realizations, `Composite`s and `Leaf`s.

3. `Component` contains an attribute `children` which is a list of `Composite` instance references and the methods `addChild()` and `removeChild()` to attach/detach `Composite`s. It also has `execute()` which an implemented method from `Component`.

4. `Leaf` contains the method `execute()` as well.

5. When a `Composite`'s execute is invoked, it calls invokes all of its children's`execute()`. When `Leaf`'s execute is invoked it performs, leaf related behavior.

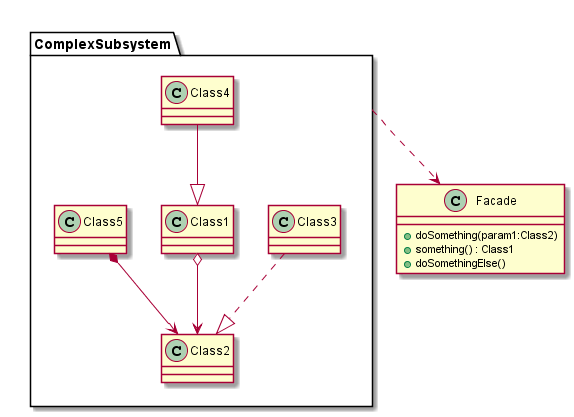

## Facade (Optional Read)

### Problem

When your system becomes large enough, parts of the system which is responsible for a single operation may involve interactions between multiple classes. Creating flexible and maintainable systems tend to look like this.

Looking from the outside, simple functionality (like borrowing a book or depositing money to an account) will appear complex since it involves multiple lines of object interaction.

### Solution

To solve this issue, you create a straightforward interface, that contains methods to encapsulate complicated functionality in your subsystem. Instead of using the internal classes to perform some functionality, you call the facade interface's method instead.

### Why this is elegant

- Implementing this pattern encapsulates complicated subsystem behavior into simple straightforward functions.

## Optional Readings

Shvets A. (2018) [Structural Patterns](https://sourcemaking.com/design_patterns/structural_patterns) Accessed August 31, 2020