# Intro to Solidity

<details><summary><b>Previous Section Recap</b></summary><br/>

In the previous week, we learned about how systems and developers communicate with the Ethereum computer. The flow we learned started at the lowest level: the [JSON-RPC API standard](https://www.jsonrpc.org/).

Specifically, the flow we built up is:

1. **JSON-RPC** to perform read requests and query data from the Ethereum computer

2. **JSON-RPC *signed* requests** to perform state changes on the Ethereum computer. The digital signature is produced cryptopgraphically using a user's private keys and the raw JSON object of the transaction.

3. Tools like [**Ethers.js**](https://docs.ethers.org/v5/) and the [**Alchemy SDK**](https://www.alchemy.com/sdk) are used to abstract the low-level away from us as developers. They still use JSON-RPC under the hood, but hide away any low-level complexities, which is great for developers. Master these tools! 🛠

</details>

### A First Look at [Solidity](https://docs.soliditylang.org/en/v0.8.11/)

As per the [official docs](https://docs.soliditylang.org/en/v0.8.11/), Solidity is an object-oriented, high-level language for implementing smart contracts. It is a language that closely resembles other popular programming languages like C++, Python and JavaScript.

> Solidity particularly resembles JavaScript! 👀

A decision that the early Ethereum founders had to make was: what language to use for the eventual Ethereum computer? It was decided that the creation of a new language would be more appropriate; Solidity is specifically designed to be compiled and run on the EVM.

Here are some important properties of the Solidity language:

- **statically-typed** (fancy term meaning variables must be defined at compile time)

- **supports inheritance**: (specifically, smart contract inheritance chains)

- **libraries**

- **complex user-defined types**, among other features

Solidity is a programming language used to write smart contracts.

> P.S.: There are many smart contract programming languages! We like to focus on Solidity because it has a very active developer ecosystem. [Vyper](https://vyper.readthedocs.io/en/stable/) is a cool language to explore too! 🐍

## Smart Contracts

Since we are focusing on Solidity, the language used to build EVM-compatible smart contracts, we should first also cover **smart contracts**.

### Smart Contracts - The Theoretical Approach

[Nick Szabo](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nick_Szabo), a famous computer scientist and cypherpunk, ideated the original concept and cointed the term smart contracts.

In his [1996 paper](https://www.fon.hum.uva.nl/rob/Courses/InformationInSpeech/CDROM/Literature/LOTwinterschool2006/szabo.best.vwh.net/smart_contracts_2.html), Szabo states the formal definition behind the early concept:

"A **smart contract** is a set of promises, specified in digital form, including protocols within which the parties perform on these promises."

The theoretical approach is for us to gain an understanding of the generalizec concept behind smart contracts... basically that they are typical contracts but in digital form and have stronger enforcement parameters.

### Smart Contracts - The Ethereum Approach

A smart contract is simply a program that runs on the Ethereum computer. More specifically, a smart contract is a collection of code (**functions**) and data (**state**) that resides on a specific address on the Ethereum blockchain. These are written in Solidity which means they must be compiled into bytecode first in order to be EVM-compatible.

### Smart Contracts - Properties 🛠

Smart contracts inherit many awesome cryptographic properties directly from the Ethereum computer. Mainly, smart contracts are:

- **permissionless**: *anyone* can deploy a smart contract to the Ethereum computer

> The only requirement here is some ETH in order to pay for gas fees! ⛽️

- **composable**: smart contracts are globally available via Ethereum, so they can be thought of as open APIs for anyone to use

> Functions in smart contracts can be thought of as globally accessible API endpoints! 🤯

### Smart Contracts - The Vending Machine ⛽️

In '[The Idea of Smart Contracts](https://www.fon.hum.uva.nl/rob/Courses/InformationInSpeech/CDROM/Literature/LOTwinterschool2006/szabo.best.vwh.net/idea.html)', published in 1997, Szabo states:

`“A canonical real-life example, which we might consider to be the primitive ancestor of smart contracts, is the humble vending machine.” `

Basically, he is saying that vending machines are a great analogous way to understand the concept of smart contracts. Why? Well because they function pretty much the same! A vending machine is a machine that you program some set logic into. That set logic dictates how users will interact with the machine. A vending machine's logic is pretty simple:

1. If you deposit sufficient money into the machine...

2. ... then select a drink that is priced *below or equal to* the amount of money you deposited...

3. ... then the machine will provide you the drink you selected.

In simpler terms, here is a quick formula representing the logic behind a simple vending machine:

**`money`** + **`drink_selection`** = **`drink dispensed`**

A smart contract, just like a vending machine, has logic programmed directly into it. That logic sets up how users must interact with the contract. If users interact outside of the scope of the programmed logic, then the program fails. Just like if you choose not to deposit money in a vending machine, it will simply not dispense a drink to you. Same with a smart contract! But smart contracts are cooler! And we can't wait to see you build em like a psycho-builder!! 💥🧑💻👩💻

## Back to Solidity

Ok, now that we've framed a conceptual understanding to smart contracts (smart contracts = really fancy digital vending machines with cryptopgrahic powers!), it's time to come back to our main focus: Solidity.

### Solidity - The Contract 📜

```solidity=

// SPDX-License-Identifier: MIT

pragma solidity ^0.8.4;

contract MyContract {

}

```

Let's the get the basics out of the way. Line by line:

`Line 1` - This is a line you will typically always see as the first line of most smart contracts. This line for the developer to specify what license rules fall on that specific smart contract.

`Line 2` - The `pragma` line tells us which version of Solidity to compile the smart contract with. The above tells us the contract will be compiled on `^0.8.4`.

`Lines 4-6` - The `contract` scope - anything inside is specific to `MyContract`. The `contract` keyword behaves eerily similar to the `class` keyword of JavaScript****

> Check out all of the licenses you can use for your smart contracts [here](https://spdx.org/licenses/).

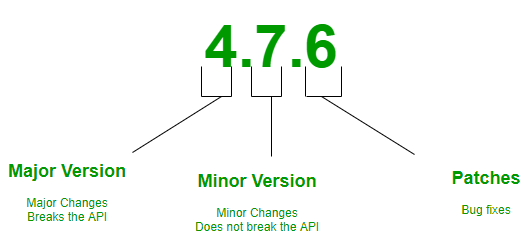

#### Solidity Uses Semantic Versioning

We are early! We are still on Solidity major version `0` which means the minor versions act as breaking changes (something major versions typically do) until the Solidity team feels like the language is ready for major version `1`.

### Solidity - Constructor

Let's add a `constructor()` to the skeleton Solidity code started above:

```solidity=

// SPDX-License-Identifier: MIT

pragma solidity ^0.8.4;

contract MyContract {

constructor() {

// called only ONCE on contract deployment

}

}

```

`Lines 5-7` - The `constructor()` function is called only once during deployment and completely discarded thereafter. It is typically used to specify state when deploying a contract. For example, if you are deploying a new DAO smart contract, the `constructor()` would make a great place to initialize it directly with specific state like an array of member addresses or a boolean flag to indicate whether the DAO will accept proposals on deployment.

### Solidity - State Variables

You might be wondering what is meant by a constructor specifying state at deployment... typically, a smart contract will contain **state variables** (let's keep adding to the same block of code!):

```solidity=

// SPDX-License-Identifier: MIT

pragma solidity ^0.8.4;

address owner;

bool isHappy;

contract MyContract {

constructor(address _owner, bool _isHappy) {

owner = _owner;

isHappy = _isHappy;

}

}

```

`Lines 4-5` - These lines *declare* two state variables: `owner` and `isHappy`. They are initialized to their default values (`0x0` and `false` respectively) if no explicit initialization is performed.

`Line 8` - Notice the smart contract's constructor now requires two parameters: an `address` and `bool` type respectively. This means the constructor expects you to pass two values as arguments at deploy time.

> Notice the `_owner` and `_isHappy` variables have underscore preceding them? This is to prevent [variable shadowing](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Variable_shadowing). 👻

`Lines 9-10` - These lines are executed as soon as the smart contract is deployed, which means the state variables declared at the top of the contract receive the value passed in by the deployer.

> A typical script deployment for the constructor above, written in JS, might look like this:

```js

// this line deploys a smart contract that sets the `owner` state variable to `0x38..CB` and the `isHappy` state variable to `true`

const myContractInstance = await contract.deploy('0x38cE03CF394C349508fBcECf8e2c04c7c66D58CB', true)

```

#### Solidity - State Variables Visibility

Let's add visibility to the state variables above:

```solidity=

// SPDX-License-Identifier: MIT

pragma solidity ^0.8.4;

address public owner;

bool public isHappy;

contract MyContract {

constructor(address _owner, bool _isHappy) {

owner = _owner;

isHappy = _isHappy;

}

}

```

`Lines 4-5` - These are the exact same lines as the above snippet *but* we've added a visibility of `public` to the contract's state variables

When you make state variables `public`, an automatic "getter" function is created on the contract. This just means the variable is publically accessible via a `get` call.

> 🚨 State variables can be declared as **`public`**, **`private`**, or **`internal`** but NOT **`external`**.

### Solidity - Numbers

Let's add a `uint` and an `int` state variable to our code:

```solidity=

// SPDX-License-Identifier: MIT

pragma solidity ^0.8.4;

address public owner;

bool public isHappy;

uint public x = 10;

int public y = -50;

contract MyContract {

constructor(address _owner, bool _isHappy) {

owner = _owner;

isHappy = _isHappy;

}

}

```

`Lines 6-7` - We've added two new state variables to `MyContract` and initialized them directly to `10` and `-50`. In Solidity there are `uint` and `int` variables used to represent numbers. An **unsigned integer** has no sign.

#### Numbers Have Different Sizes!

The `uint` and `int` variables have set sizes:

```solidity=

contract MyNumberContract {

uint8 x = 255;

uint16 y = 65535;

uint256 z = 10000000000000000000;

}

```

> A `uint` by default is 256 bits. So labelling a state variable as `uint` is the exact same as labelling it with `uint256`.

#### Familiar Math Operators ➕

Solidity has many of the same familiar math operators:

```solidity=

contract MyNumberContract {

uint x = 100 - 50;

uint y = 100 + 22;

uint z = 100 / 20;

}

```

### Solidity - [Data Types](https://docs.soliditylang.org/en/v0.8.17/types.html)

The following are all data types available on Solidity:

- [`boolean`](https://docs.soliditylang.org/en/v0.8.17/types.html#booleans): declared as `bool`

- [`string`](https://docs.soliditylang.org/en/v0.8.17/types.html#string-literals-and-types): declared as `string`

- [`integers`](https://docs.soliditylang.org/en/v0.8.17/types.html#booleans): declared as either `uint` or `int`

- [`bytes`](https://docs.soliditylang.org/en/v0.8.17/types.html#bytes-and-string-as-arrays): decalred as `bytes`

- [`enums`](https://docs.soliditylang.org/en/v0.8.17/types.html#enums)

- [`arrays`](https://docs.soliditylang.org/en/v0.8.17/types.html#enums)

- [`mappings`](https://docs.soliditylang.org/en/v0.8.17/types.html#mapping-types)

- [`structs`](https://docs.soliditylang.org/en/v0.8.17/types.html#mapping-types)

#### Solidity - `address` and `address payable`

You've probably seen similar variations of most of the types listed above. There is also a very important *Solidity-specific* type called `address`. As per the Solidity docs:

"The address type comes in two flavours, which are largely identical:

`address`: Holds a 20 byte value (size of an Ethereum address).

`address payable`: Same as `address`, but with the additional members `transfer` and `send`."

> Whenever you see the keyword `payable`, that's just Solidity fancy lingo for: "this can accept money!". Don't worry, we'll break down the `payable` keyword much further...

`address` and `address payable` are first-class types, meaning they are more than simple strings holding some Ethereum address value. Any `address`, either passed in to a function or cast from a contract object, [has a number of attributes and methods directly accessible on it](https://docs.soliditylang.org/en/v0.8.17/types.html#members-of-addresses):

- `address.balance`: returns the balance, in units of `wei`

- `address.transfer`: sends ether to a `address payable` type

> Curious to know a smart contract's own balance? Just use `address(this).balance`! ✅

## Smart Contract Context

> This short section is really important to understand! 🧠

When a smart contract function is called via a transaction, the called function gets some extra information passed to it. Within a smart contract function you’ll have access to these **context** variables, including:

1. **Message Context (msg)**

- `msg.sender` - returns the current transaction sender address

- `msg.value` - returns the `value` property of the current transaction

2. **Transaction Context (tx)**

- `tx.gasLimit` - returns the `gasLimit` property of the current tx

3. **Block Context (block)**

- `block.number` - returns the current block `number`

- `block.timestamp` - returns the current block `timestamp`

#### Other Ways to Think About `msg.sender`

- `msg.sender`: Who is currently sending this transaction?

- `msg.value`: How much `value` does this transaction carry?

## Suggested Reading

- [Mastering Ethereum](https://github.com/ethereumbook/ethereumbook)

- Chapter 7: Smart Contracts & Solidity

- Chapter 9: Smart Contract Security

- Chapter 13: EVM

- [Smart Contracts: Building Blocks for Digital Markets](https://www.fon.hum.uva.nl/rob/Courses/InformationInSpeech/CDROM/Literature/LOTwinterschool2006/szabo.best.vwh.net/smart_contracts_2.html)

- [The Idea of Smart Contracts](https://www.fon.hum.uva.nl/rob/Courses/InformationInSpeech/CDROM/Literature/LOTwinterschool2006/szabo.best.vwh.net/idea.html)

- [**Solidity by Example**](https://solidity-by-example.org/)

## Conclusion

We learned a lot of the basic stuff that powers Solidity such as data types and constructors. Using Solidity, we can write cutting edge smart contracts, which we learned to conceptualize as just really smart and cryptographically secure vending machine descendants.

The very important takeaways from this section are:

- `msg.sender` (understand message context!)

- `address` (understand the EVM-specific types)

In the next section, we'll look at [Solidity functions](https://www.fon.hum.uva.nl/rob/Courses/InformationInSpeech/CDROM/Literature/LOTwinterschool2006/szabo.best.vwh.net/idea.html).