---

title: 'Rust Lectures'

disqus: hackmd

---

# Table of Content

[TOC]

## Reference

- [The Rust Programming Language](https://doc.rust-lang.org/book/) (TRPL)

- [UPenn CIS 198](https://www.cis.upenn.edu/~cis198/)

- [Rust Design Patterns](https://rust-unofficial.github.io/patterns/)

# 09/03

In the first class, we should first do course introduction. it will take about 10 minutes.

Then, we will introdu the basic ideas in rust. I will follow TRPL to do this, which means I will introduce

1. install/update `rustc`

2. cargo basics

3. variables and mutability

4. data types

5. comments

6. control flow

## [Course introduction](http://www.cs.umd.edu/class/fall2021/cmsc388Z/)

## Why Rust?

### Rust Overview

"Rust is a systems programming language that runs blazingly fast, prevents segfaults, and guarantees thread safety."

In other words: Rust is designed for speed, safety, and concurrency.

#### What is "Systems Programming"?

Areas of systems programming:

- Operating Systems

- Device Drivers

- Embedded Systems

- Real Time Systems

- Networking

- Virtualization and Containerization

- Scientific Computing

- Video Games

Other systems languages include: C, C++, Ada, D.

Like C and C++, Rust gives developers fine control over the use of memory, and maintains a close relationship between the primitive operations of the language and those of the machines it runs on, helping developers anticipate the costs (time and space) of operations.

#### Who uses Rust?

- [Amazon](https://aws.amazon.com/blogs/aws/firecracker-lightweight-virtualization-for-serverless-computing)

- [Facebook](https://developers.libra.org/)

- [Firefox](https://servo.org)

- [Discord](https://blog.discord.com/why-discord-is-switching-from-go-to-rust-a190bbca2b1f)

- [Dropbox](https://dropbox.tech/infrastructure/rewriting-the-heart-of-our-sync-engine)

- [Coursera](https://medium.com/coursera-engineering/rust-docker-in-production-coursera-f7841d88e6ed)

"For five years running, Rust has taken the top spot as [the most loved programming language](https://insights.stackoverflow.com/survey/2020#technology-most-loved-dreaded-and-wanted-languages-loved)."

Now a [top 20 language](https://www.reddit.com/r/rust/comments/hz7dfp/rust_is_now_a_top_20_language_in_all_of_the_5/) in most language popularity rankings, and one of the fastest-growing:

[Second most used language](https://app.powerbi.com/view?r=eyJrIjoiZTQ3OTlmNDgtYmZlMS00ZTJmLTkwYTgtMWQyMTkxNWI5NGM1IiwidCI6IjQwOTEzYjA4LTQyZTYtNGMxOS05Y2FiLTRmOWZlM2U0YzJmZCIsImMiOjl9) for Advent of Code this year, after Python:

#### Why Rust?

- Fast

- Safe -> statically typed, and compile time checked for memory safety

- Trustworthy concurrency

In particular, Rust's goals of memory safety and trustworthy concurrency are what makes it most unique. These concepts -- in particular the issues surrounding data ownership -- can be both the most surprising and the most rewarding parts of learning Rust.

### Type Safety and Memory Safety

A language is said to be [memory-safe](https://www.zdnet.com/article/microsoft-70-percent-of-all-security-bugs-are-memory-safety-issues/) if all programs written in that language have defined semantics for all possible states.

#### Aside: [Typing](https://medium.com/android-news/magic-lies-here-statically-typed-vs-dynamically-typed-languages-d151c7f95e2b)

**Rust is a [type safe and statically typed](http://www.cs.umd.edu/class/spring2021/cmsc330/lectures/26-types.pdf) language:**

**C and C++ are not type safe!** Undefined Behavior is the root of all evil.

#### Undefined Behavior

- buffer overruns.

Your program will access elements beyond the end or before the start of an array.

```cpp

int main() {

int x = 1, *p = &x;

int y = 0, *q = &y;

*(q+1) = 5; // overwrites p

return *p; // crash

}

```

- dangling pointers (uses of pointers to freed memory)

… which can happen via the stack, too:

```cpp

int *foo(void) { int z = 5; return &z; }

void bar(void) {

int *x = foo();

*x = 5; /* oops! */

}

```

[Heartbleed](https://xkcd.com/1354/).

- Problem: C and C++ allow for direct memory dereference, no checking.

Systems languages are what we built everything on top of! Even other languages are built on top of C and C++:

- Java Virtual Machine

- CPython

**Why then, do we not check things at runtime?**

#### Null References -- Billion Dollar Mistake

> I call it my billion-dollar mistake. It was the invention of the null reference in 1965... My goal was to ensure that all use of references should be absolutely safe, with checking performed automatically by the compiler. But I couldn't resist the temptation to put in a null reference, simply because it was so easy to implement. This has led to innumerable errors, vulnerabilities, and system crashes, which have probably caused a billion dollars of pain and damage in the last forty years. [name=Tony Hoare]

### Performance

- **Zero Cost Abstraction:** In general, C++ amd rust implementations obey the zero-overhead principle:

What you don’t use, you don’t pay for. And further: What you do use, you couldn’t hand code any better.

Rust performs similar (even [slightly better](https://benchmarksgame-team.pages.debian.net/benchmarksgame/fastest/rust-gpp.html)) than C++.

### Concurrency

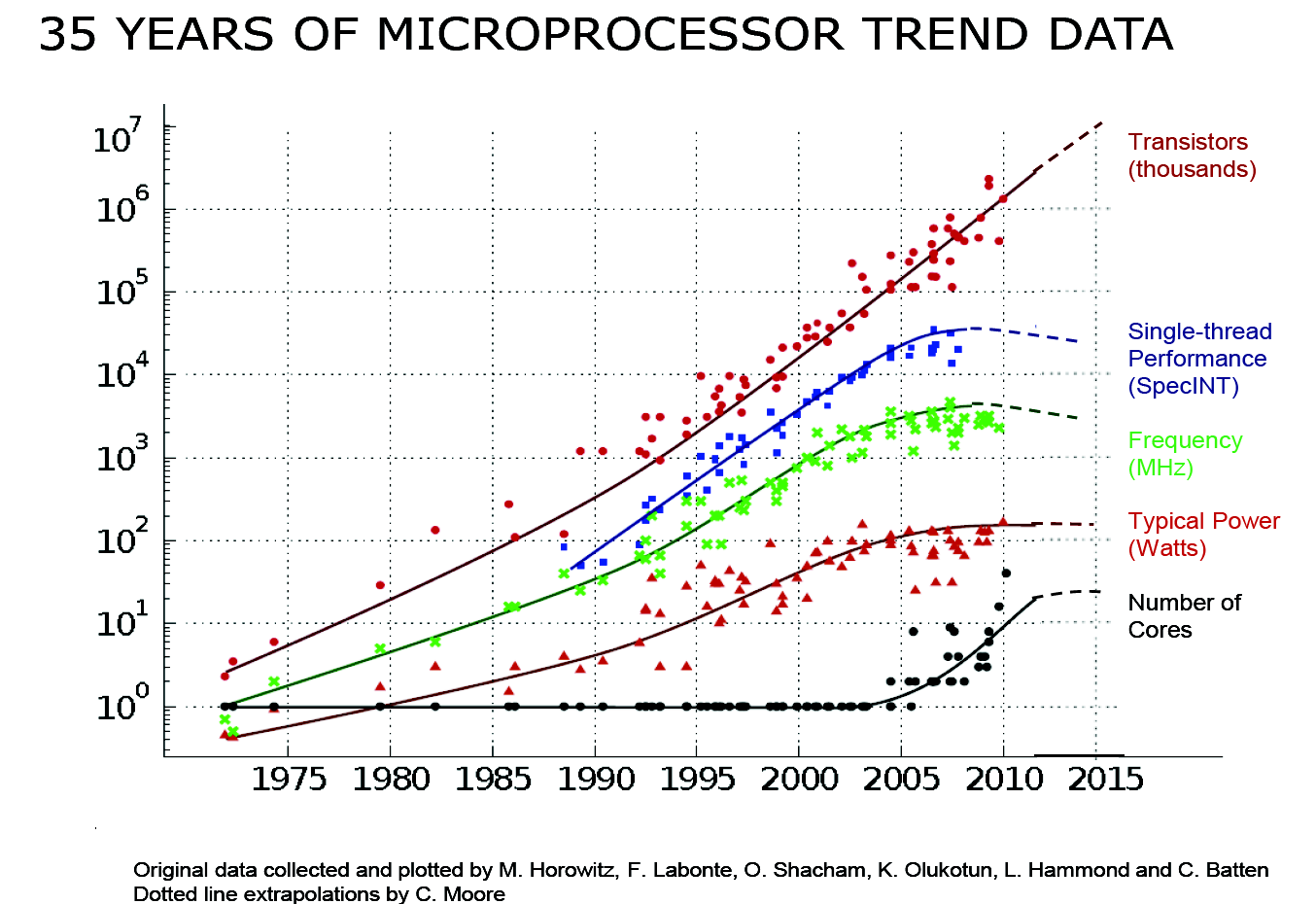

- Computers are multicore, need for parallelism.

- Concurrency is hard:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Therac-25

- No data race in rust (achieved by ownership)

### Examples of Rust Safety

No null pointer dereferences. (Not unique to Rust)

Your program will not crash because you tried to dereference a null pointer.

The problems with null

1) Used to represent a missing value:

`String getValue(HashTable<String, String> t)`;

3) Use to represent an error:

`void* malloc(size_t size)`

5) It is very easy to ignore.

```rust

// Optional Values:

enum Option<P> {

Some(P),

None

}

```

Still compiles down to pointer and null! But to use the value, one need to unwrap the value from `Option<P>`.

#### Handling Possible Errors

```rust

enum Result<T, E> {

Ok(T),

Err(E),

}

fn read(&mut fd: FileDescriptor, buf: &mut [u8]) -> Result<usize, std::io::Error>;

```

#### Memory Management

- **C and C++**: Manual memory management.

- **Python and Java**: Automatic Memory Management via a garbage collector.

- A garbage collector traces pointers in use by the program, starting from the stack and global variables.

- Drawback: Time critical code, performance, runtime/portability

- **Rust**:

- [Reference counting]() + [Non-Lexical Lifetimes](http://blog.pnkfx.org/blog/2019/06/26/breaking-news-non-lexical-lifetimes-arrives-for-everyone/#How.was.NLL.implemented)

- Fast, safe and smart.

## Rust install/update

To check whether you have Rust installed correctly, run this in your terminal:

```bash

$ rustc --version

```

you will see the version number

```bash

$ rustc 1.54.0 (a178d0322 2021-07-26)

```

If you have different version or you don't have rust installed:

- If you have not installed Rust in your computer, install it through [Rust-lang website](https://www.rust-lang.org/tools/install).

- If you have it installed in your computer, update it!

```bash

$ rustup update stable

```

To play with Rust online in your browser, go rust-lang playground (https://play.rust-lang.org).

## Hello Cargo

Cargo is Rust’s build system and package manager. Cargo comes installed with Rust if you used the official installers described above and in [TRPL](https://doc.rust-lang.org/book/ch01-01-installation.html#installation). Cargo is so frequently used so it has its own [book](https://doc.rust-lang.org/cargo/)! After installing Rust, You can check your Cargo version by:

```bash

$ cargo --version

```

Cargo integrated many useful commands to help you manage your projects. You can create, run, build, check and test your project with cargo's easy commands!

- Creating a Project with Cargo

```bash

$ cargo new hello_cargo

$ cd hello_cargo

```

- Building and Running a Cargo Project

```bash

$ cargo build

```

```bash

$ cargo run

```

- Building for Release

```bash

$ cargo build --release

```

- Check the format of your code

```bash

$ cargo fmt

```

- check the syntax of your code

```bash

$ cargo clippy

```

### build a project from GitHub

```bash

$ git clone example.org/someproject

$ cd someproject

$ cargo build

```

## Hello VSCode

I suggest you to write your rust code in [VS code](https://code.visualstudio.com/) with `rust-analyzer` [extention](https://github.com/rust-analyzer/rust-analyzer).

## Hello world!

Create a `hello_world` rust project using Cargo:

```

cargo new hello_world

cd hello_world

code .

```

You folder will contain the following files.

No `code` command on mac? [Here](https://code.visualstudio.com/docs/setup/mac) is the solution.

- `src/main.rs`

- `Cargo.toml`

#### check fmt

- Check the format of your code

```bash

$ cargo fmt

```

If you add some empty line in the `main()`, `cargo fmt` will clean it for you.

#### clippy it!

```bash

$ cargo clippy

```

if you define an unused variable, for example

```rust

fn main() {

let a = 1;

println!("Hello, world!");

}

```

`cargo clippy` will complain.

### Run it!

```bash

cargo run

```

### Build it

```bash

cargo run

```

#### Build release

- Building for Release

```bash

$ cargo build --release

```

## Common Programming Concepts

### Variables and Mutability

In rust, variables are defined via keyword `let`. By default, variables are immutable, except you specify it.

```rust=

fn main() {

let x = 37;

let y = x + 5;

y

} // 42

```

```rust=

fn main() {

let x = 37;

x = x + 5;//err

x

}

```

```rust=

fn main() {//err:

let x:u32 = -1;

let y = x + 5;

y

}

```

```rust=

fn main() {

let x = 37;

let x = x + 5;

x

}//42

```

```rust=

fn main() {

let mut x = 37;

x = x + 5;

x

}//42

```

```rust=

fn main() {

let x:i16 = -1;

let y:i16 = x+5;

y

}//4

```

### Differences Between Variables and Constants

```rust=

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

const MAX_POINTS: u32 = 100_000;

}

```

1. constants are defined using the `const` keyword.

2. You are not allowed to `mut` constants.

3. You **must** annotate the type of constants.

4. Constants are valid for the entire time a program runs, within the scope they were declared in.

5. constants cannot be set as the result of a functional call or any other value that could only be computed at runtime.

### Shadowing

```rust=

fn main() {

let x = 5;

let x = x + 1;

let x = x * 2;

println!("The value of x is: {}", x);

}

```

The result will be `12`.

Shadowing is useful if

1. a value needs a few modifications in the whole program

2. we want to change the type of the value but reuse the same name.

```rust=

let spaces = " ";

let spaces = spaces.len();

```

but rust will complain if we do

```rust=

let mut spaces = " ";

spaces = spaces.len();

```

because we want to change the value of the variable as well.

### Data Type

#### Scalar Types

A scalar type represents a single value. Rust has four primary scalar types:

##### 1. integers

The `isize` and `usize` types depend on the kind of computer your program is running on: 64 bits if you’re on a 64-bit architecture and 32 bits if you’re on a 32-bit architecture.

You can write integer literals in any of the forms below. Note that all number literals except the byte literal allow a type suffix, such as 57u8, and _ as a visual separator, such as 1_000.

##### 2. floating-point numbers

```rust=

fn main() {

let x = 2.0; // f64, default

let y: f32 = 3.0; // f32

}

```

##### Numeric Operations

```rust=

fn main() {

// addition

let sum = 5 + 10;

// subtraction

let difference = 95.5 - 4.3;

// multiplication

let product = 4 * 30;

// division

let quotient = 56.7 / 32.2;

// remainder

let remainder = 43 % 5;

}

```

4. Booleans

```rust=

fn main() {

let t = true;

let f: bool = false; // with explicit type annotation

}

```

The main way to use Boolean values is through conditionals, such as an if expression.

6. characters

```rust=

fn main() {

let c = 'z';

let z = 'ℤ';

let heart_eyed_cat = '😻';

}

```

Rust’s `char` type is four bytes in size and represents a Unicode Scalar Value, which means it can represent a lot more than just ASCII. Accented letters; Chinese, Japanese, and Korean characters; emoji; and zero-width spaces are all valid `char` values in Rust. Unicode Scalar Values range from `U+0000` to `U+D7FF` and `U+E000` to `U+10FFFF` inclusive. However, a “character” isn’t really a concept in Unicode, so your human intuition for what a “character” is may not match up with what a char is in Rust.

#### Compound Types

Compound types can group multiple values into one type. Rust has two primitive compound types: tuples and arrays.

##### The Tuple Type

A tuple is a general way of grouping together a number of values with a variety of types into one compound type. **Tuples have a fixed length**: once declared, they cannot grow or shrink in size. Tuple will be allocated on the stack.

```rust=

fn main() {

let tup: (i32, f64, u8) = (500, 6.4, 1);

}

```

**destructuring**

In addition to destructuring through pattern matching, we can access a tuple element directly by using a period (`.`) followed by the index of the value we want to access. For example:

```rust=

fn main() {

let tup = (500, 6.4, 1);

let (x, y, z) = tup;

println!("The value of y is: {}", y);

}

```

This program creates a tuple, `x`, and then makes new variables for each element by using their respective indices. As with most programming languages, the first index in a tuple is 0.

##### The Array Type

Another way to have a collection of multiple values is with an array. Unlike a tuple, every element of an array **must have the same type**. Arrays in Rust are different from arrays in some other languages because arrays in Rust have a **fixed length**, like tuples. arrays are allocated on the stack.

1. Creating an array

```rust=

fn main() {

let a: [i32; 5] = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5];

}

```

Here, `i32` is the type of each element. After the semicolon, the number `5` indicates the array contains five elements.

```rust=

let a = [3; 5];

```

The array named `a` will contain `5` elements that will all be set to the value `3` initially. This is the same as writing `let a = [3, 3, 3, 3, 3]`; but in a more concise way.

2. Accessing array elements

An array is a single chunk of memory allocated on the stack. You can access elements of an array using indexing, like this:

```rust=

pub fn array() {

// Size is hardcoded for arrays.

// There space is allocated directly in the binary.

let a = [1, 2, 3];

let zeroes = [0; 1000];

let b: [i32; 3] = [1, 2, 3];

// Typical example

let input_files = ["input/input_1.txt", "input/input_2.txt"];

let first = a[0];

let second = a[1];

// println!("{:?}", a + a);

// a.push(3);

}

```

3. Buffer overflow?

**NEVER**. Rust checks the bounds at both compile time and run time. You will get an OOB error.

#### Statements and Expressions

- Statements are instructions that perform some action and **do not return a value. **

- Expressions evaluate to a resulting value.

```rust=

// function body

fn main() {

let x = 5; // statement

let y = {

let x = 3; // statement

x + 1 // expression

}; // statement

println!("The value of y is: {}", y); // statement

}

```

In the function body, this block is an expression.

```rust=

{

let x = 3; // statement

x + 1 // expression

}

```

### Comments

In each line, everything after a double reversed slash `//` can be used to mark comments.

```rust=

// I am a comment.

a = 5; // I am also a comment.

```

Before a function definition, a triple reversed slash `///` can be used to mark the description of a function.

```rust=

/// I am the description of function `a_function()`.

fn a_function() {}

```

### Control Flow

#### `if`

```rust=

fn main() {

let number = 6;

let sign = if number < 0 {

-1

} else if number == 0 {

0

} else {

1

};

}

```

#### loops

##### `loop`

The loop keyword tells Rust to execute a block of code over and over again forever or until you explicitly tell it to stop.

```rust=

fn main() {

loop {

println!("again!");

}

}

```

##### `while`

```rust=

fn main() {

let mut number = 3;

while number != 0 {

println!("{}!", number);

number -= 1;

}

println!("LIFTOFF!!!");

}

```

##### `for`

```rust=

fn main() {

let a = [10, 20, 30, 40, 50];

let mut index = 0;

while index < 5 {

println!("the value is: {}", a[index]);

index += 1;

}

}

```

Rust provides a way to **iterate** over a collection

```rust=

fn main() {

let a = [10, 20, 30, 40, 50];

for element in a.iter() {

println!("the value is: {}", element);

}

}

```

If you know exactly which elements you want to iterate, used `Range`:

```rust=

fn main() {

let a = [10, 20, 30, 40, 50];

for element in (1..4).rev() {

println!("the value is: {}", element);

}

}

```

## Testing

In any language, there is the need to test code.

In most languages, testing requires extra libraries:

- Minitest in Ruby

- Ounit in Ocaml

- Junit in Java

Testing in Rust is a first-class citizen!

The testing framework is **built into cargo**.

### Unit testing

Unit testing is for local or private functions

Put such tests in the same file as your code

- Use `assert!` to test that something is true

- -Use `assert_eq!` to test that two things that implement the PartialEq trait are equal.

- E.g., integers, booleans, etc.

```rust=

fn bad_add(a: i32, b: i32) -> i32 {

a - b

}

#[cfg(test)]

mod tests {

#[test]

fn test_bad_add () {

assert_eq!(bad_add(1,3),3);

}

}

```

### Integration testing

Integration testing is for APIs and whole programs

(This is how we grade your projects).

- Create a tests directory

- Create different files for testing major functionality

- Files don’t need #[cfg(test)] or a special module

- But they do still need #[test] around each function

- Tests refer to code as if it were an external library

- Declare it as an external library using extern crate

- Include the functionality you want to test with use

`src/lib.rs`

```rust=

pub fn add(a: i32, b: i32) -> {

a + b

}

```

`tests/test_add.rs`

```rust=

extern crate your_project_name // this will tell rust you have an external source

use your_project_name::add; // this will tell rust you will use add() function from the extern source

#[test]

pub fn test_add () {

assert_eq!(add(1,2),3);

}

#[test]

pub fn test_negative_add() {

assert_eq!(add(1,-2),-1);

}

```

# 09/10

Every package in Rust has complete documentation. This is automatically generated by the Rust compiler when building the package.

- For *the rust standard library* `std`, you can find the documentation [here](https://doc.rust-lang.org/std/).

- For external crates from [crates.io](https://crates.io), each package has its documentation. For example, [`rand`](https://docs.rs/rand/0.8.4/rand/).

- For your own package, `cargo doc --open` will bring up the documentation. (so, please write a short description for your code!)

Next time when you are unclear about anything of a package, read their doc!

In this week's lecture, we will cover:

1. Ownership

2. references

3. borrowing

4. slices

## Collections

We will explain ownership using *String*, which is a member of Rust collection data type.

- String

- Vector

- HashMap

### String

```rust=

let s_literals = "hello";

let s1 = String::from(s_literals);

let s = &s1;

let s_slice = &s1[..]

```

There are four common types that relate to string.

- *String*: like `s1`. A String is stored as a vector of bytes (`Vec<u8>`), but guaranteed to always be a valid UTF-8 sequence. A string is heap-allocated, growable, and not null-terminated. Each `string` is allocated on the heap and consists of three parts:

- a **pointer** to the memory that holds the contents of the string.

- The **length** is how much memory, in bytes, the contents of the String is currently using.

- The **capacity** is the total amount of memory, in bytes, that the String has received from the allocator.

- *String Literals*: like `s_literals`, String literal is hardcoded into the text of our program. It is immutable and must have known fixed length at compile time. More examples can be found in [Rust by Example](https://doc.rust-lang.org/rust-by-example/std/str.html) and [TRPL](https://doc.rust-lang.org/book/ch04-01-what-is-ownership.html). You can regard string literals as a string slice that points to a specific point of the binary.

- The reference of a *String*: like `s`, it allows us to refer to the string without taking ownership of it.

- **string slice**: like `s_slice`. This type allows us to take a specific part of a string (i.e., substring). It consists of two parts: a pointer to the start of the data and a length.

UTF-8 is a variable-length character encoding

- The first 128 characters (US-ASCII) need one byte

- The next 1,920 characters need two bytes, which covers the remainder of almost all Latin-script alphabets, … up to 4 bytes

You may not index a string directly; Rust stops you because you could end up in the middle of a character! (more details at [here](https://doc.rust-lang.org/book/ch08-02-strings.html).)

```rust=

let s1 = String::from("hello");

let h = s1[0]; // rejected

```

#### Operate a string

```rust=

let mut s1 = "hello".to_string();

let mut s2 = String:: from("hello");

s1.push_str(", rust");

//iterating over the characters in a string

for c in s1.chars() {

println!("{:?}", c)

}

```

### Vector

Like `array`, vector `Vec` can store a single type of values next to each other. Unlike `array`, `Vec` is allocated in the heap and doesn't need to have a fixed length at compile time.

**you can find the entire list of methods for `Vec` and any data type in rust from their [documentation](https://doc.rust-lang.org/std/vec/struct.Vec.html#method.from_raw_parts).**

#### operating a vector

```rust=

// create a empty vector

let mut v: Vec<i32> = Vec::new();

// push in and pop off value from vector

v.push(5);

v.push(6);

v.pop();

// create a vector with initialized values

let v = vec![5,5,5,5];

let v = vec![5;4];

```

#### iterating over the values in a vector

```rust=

let v = vec![100, 32, 57];

for i in &v {

println!("{}", i);

}

```

if you want to change the values as well, we take the mutable reference:

```rust=

let mut v = vec![100, 32, 57];

for i in &mut v {

*i += 50;

}

```

#### sliced a vector

```rust=

for i in &mut v[5..8] {

*i += 50;

}

```

#### Generics and Polymorphism

The std library defines `Vec<T>` where `T` can be instantiated with a variety of types

- `Vec<char>` is a vector of characters

- `Vec<&str>` is a vector of string slices

This can also be used in functions:

```rust=

fn id<T>(x:T) -> T { x }

```

In this definition, `<T>` indicates the types this function is able to take.

### HashMap

The last of our common collections is the hash map. Hash maps store their data on the heap.

The type `HashMap<K, V>` stores a mapping of keys of type `K` to values of type `V`. When using `HashMap`, you need to bring it into scope by specifying `use std::collections::HashMap; ` before you use it.

```rust=

fn main() {

use std::collections::HashMap;

let mut scores = HashMap::new();

// insert values

scores.insert(String::from("Blue"), 10);

scores.insert(String::from("Yellow"), 50);

// get values

for (key, value) in &scores {

println!("{}: {}", key, value);

}

//overwrite

scores.insert(String::from("Blue"), 25);

//get or insert

let blue = scores.entry(String::from("Blue")).or_insert(50);

*blue *= 2;

}

```

or, you can initialize your `HashMap` from iterators and the `collect` method on a vector of tuples.

```rust=

use std::collections::HashMap;

let teams = vec![String::from("Blue"), String::from("Yellow")];

let initial_scores = vec![10, 50];

let mut scores: HashMap<_, _> =

teams.into_iter() // turn this variable into iterator

.zip(initial_scores.into_iter()) // zip it with another iterator

.collect(); // collect the zipped iterator as a vector of tuples.

```

## The Stack and the Heap

Both the stack and the heap are parts of memory that are available to your code to use at runtime, but they are structured in different ways.

### The stack

- The stack stores values in the order *last in, first out*.

- **All data stored on the stack must have a known, fixed size**.

- Adding data is called *pushing onto* the stack. Removing data is called *popping off* the stack.

- When your code calls a function, the values passed into the function (including, potentially, pointers to data on the heap) and the function’s local variables get pushed onto the stack. When the function is over, those values get popped off the stack.

### The heap

- when you put data on the heap, you request a certain amount of space.

- The memory allocator finds an empty spot in the heap that is big enough, marks it as being in use (by ownership), and returns a *pointer*, which is the address of that location.

- This process is called allocating on the heap and is sometimes abbreviated as just allocating.

- you can store the pointer on the stack, but when you want the actual data, you must follow the pointer.

### The Stack VS The Heap

- Pushing to the stack is faster than allocating on the heap

- because the allocator never has to search for a place to store new data; that location is always at the top of the stack.

- Accessing data on the stack is faster than accessing data in the heap

- because you have to follow a pointer to get there.

- A processor can do its job better if it works on data that is close to other data (as it is on the stack) rather than farther away (as it can be on the heap).

## Ownership

Rust’s heap memory is managed through a system of *ownership* with a set of rules that the compiler checks at compile time. **None of the ownership features slow down your program while it’s running.**

### Ownership Rules

First, let’s take a look at the ownership rules. Keep these rules in mind as we work through the examples that illustrate them:

- Each value in Rust has a variable that’s called its **owner**.

- There can only be **one owner** at a time.

- When the owner goes out of scope (when the *lifetime* is over), the value will be dropped.

Why?

- Each piece of memory has its owner. No data race!

- When the owner gets dropped, the piece of memory will be freed. No dangling pointers!

#### Heap memory

Heap memory is managed by ownership.

```rust=

{

let s1 = String::from("hello");

let s2 = s1; //x moved to y

println!("{}", s1); // error, `s1` doesn't own the value anymore.

} // s1, s2 are droped at this point.

```

when assigning `s1` to `s2`, we pass the ownership of the stored value, "hello", from `s1` to `s2`. In other words, we *move* the value from `s1` to `s2`. So `s1` cannot access the data anymore.

If we really want to keep `s1` and `s2` at the same time, we can `clone` it explicitly:

```rust=

{

let s1 = String::from("hello");

let s2 = s1.clone();

println!("s1 = {}, s2 = {}", s1, s2);

}

```

When the scope, marked by `{}` is over, rust calls `drop()` function automatically to drop `s1` and `s2`. In other words, delete these two variables and clear the memory they use.

#### stack memory

On the contrary, if we do this for values on the stack, for example

```rust=

let x: i32 = 5;

let y = x;

println!("x = {}, y = {}", x, y); //works

```

This is fOK because x has a primitive type, `i32`, whose length is known at compile-time and is stored on the stack. So, the Rust compiler will *copy* the value of `x` to `y`, so both `x` and `y` have the same value `5i32` (but are stored in a different place on the stack).

This is because `i32` has the `Copy` trait. If a type implements the `Copy` trait, the value of the type will be copied after the assignment.

#### Trait

A Trait is a way of saying that a type has a particular property

- `Copy`: objects with this trait do not transfer ownership on assignment. Instead, the assignment copies all of the object data

- `Move`: objects with this trait do transfer ownership on assignment usually so that not all of the data need be copied.

Another way of using traits: to indicate functions that a type is must implement (more later)

- Like Java interfaces

- Example: Deref built-in trait indicates that an object can be dereferenced via `*` op; compiler calls object’s `deref()` method

#### Lifetimes

The lifetime of a variable starts at the time when the variable is defined and ends after the last time that the variable is used.

While lifetime of a reference not always explicit.

```rust=

fn longest(x:&str, y:&str) -> &str {

if x.len() > y.len() { x } else { y}

} // this funcion doesn't work

```

When running this function, Rust doesn't know the lifetime of `x` and `y`. The following situation may happen:

```rust=

{

let x = String::from(“hi”);

let z;

{ let y = String::from(“there”);

z = longest(&x,&y); //will be &y

} //drop y, and thereby z

println!(“z = {}”,z);//yikes!

}

```

To fix it, we need to explicitly specify that `x` and `y` must have the same lifetime, and the returned reference shares it.

```rust=

fn longest<'a>(x:&'a str, y:&'a str) -> &'a str {

if x.len() > y.len() { x } else { y }

}

```

Note:

- Each reference to a value of type `t` has a `lifetime parameter`.

- `&t` (and `&mut t`) – lifetime is implicit

- `&'a t` (and `&'a mut t`) – lifetime `'a` is explicit

- Where do the lifetime names come from?

- When left implicit, they are generated by the compiler

- Global variables have lifetime '

- 'static

Lifetimes can also be generic

#### Lifetimes FAQ

- When do we use explicit lifetimes?

- When more than one var/type needs the same lifetime (like the longest function)

- How do I tell the compiler exactly which lines of code lifetime 'a covers?

- You can't. The compiler will (always) figure it out

- How does lifetime subsumption work?

- If lifetime `'a` is longer than `'b`, we can use `'a` where `'b` is expected; can require this with `'b: 'a`.

- Permits us to call `longest(&x,&y)`` when `x` and `y` have different lifetimes, but one outlives the other.

- Can we use lifetimes in data definitions?

- Yes; we will see this later when we define structs, enums, etc.

### Ownership Transfer in Function Calls

```rust=

fn main() {

let s = String::from("hello"); // s comes into scope, in the heap

takes_ownership(s); // s's value moves into the function...

// ... and so is no longer valid here

let x = 5; // x comes into scope, on the stack

makes_copy(x); // x would move into the function,

// but i32 is Copy, so it's okay to still

// use x afterward

} // Here, x goes out of scope, then s. But because s's value was moved, nothing

// special happens.

fn takes_ownership(some_string: String) { // some_string comes into scope

println!("{}", some_string);

} // Here, some_string goes out of scope and `drop` is called. The backing

// memory is freed.

fn makes_copy(some_integer: i32) { // some_integer comes into scope

println!("{}", some_integer);

} // Here, some_integer goes out of scope. Nothing special happens.

```

On a call, ownership passes from:

- argument to called function’s parameter

- returned value to caller’s receiver

## References and Borrowing

### Borrowing avoids transferring ownership

If we don't want a function to take ownership of our data, we can pass a reference to the function. Creating an explicit, non-owning pointer by making a reference is called `borrowing` in rust. Done with `&` ampersand operator. The opposite of referencing by using `&` is dereferencing, which is accomplished with the dereference operator, `*`.

```rust=

fn main() {

let s1 = String::from("hello");

let len = calculate_length(&s1); // &s1 has type &String

println!("The length of '{}' is {}.", s1, len);

}

fn calculate_length(s: &String) -> usize {

s.len()

}

```

### mutable reference

`&` alone doesn't give us the permission to modify the data. Remember that in Rust, everything is by default immutable. To make a mutable reference, we need to specify `&mut` when making a reference.

```rust

fn main() {

let mut s = String::from("hello");

change(&mut s);

}

fn change(some_string: &mut String) {

some_string.push_str(", world");

}

```

**REMEMBER:** Mutable references have one big restriction: you can have only one mutable reference to a particular piece of data in a particular scope.

The following code will fail

```rust=

fn main() {

let mut s = String::from("hello");

let r1 = &mut s;

let r2 = &mut s; // cannot have multiple mutable reference!

println!("{}, {}", r1, r2);

}

```

The benefit of having this restriction is that **Rust can prevent [data races](https://docs.oracle.com/cd/E19205-01/820-0619/geojs/index.html#:~:text=A%20data%20race%20occurs%20when,their%20accesses%20to%20that%20memory.) at compile-time**.

**Each piece of data in memory can have either one mutable reference or multiple immutable references.**

```rust=

fn main() {

let mut s = String::from("hello");

let r1 = &s; // no problem

let r2 = &s; // no problem

let r3 = &mut s; // BIG PROBLEM

println!("{}, {}, and {}", r1, r2, r3);

}

```

### [Non Lexical Lifetimes(NLL)](http://blog.pnkfx.org/blog/2019/06/26/breaking-news-non-lexical-lifetimes-arrives-for-everyone)

Rust has been updated to support NLL -- lifetimes that end before the surrounding scope:

```rust=

fn main() { // SCOPE TREE

//

let mut names = // +- `names` scope start

["abe", "beth", "cory", "diane"]; // |

// |

let alias = &mut names[0]; // | +- `alias` scope start

// | |

*alias = "alex"; // <------------------------ write to `*alias`

// | |

println!("{}", names[0]); // <--------------- read of `names[0]`

// | |

// | +- `alias` scope end

// +- `name` scope end

}

```

In practice, this is important when

```rust=

fn main() {

let mut s = String::from("hello");

let r1 = &s; // no problem

let r2 = &s; // no problem

println!("{} and {}", r1, r2);

// r1 and r2 are no longer used after this point

let r3 = &mut s; // no problem

println!("{}", r3);

}

```

### No Dangling References

In languages with pointers, it’s easy to erroneously create a *dangling pointer*, a pointer that references a location in memory that may have been given to someone else, by freeing some memory while preserving a pointer to that memory.

**In rust, the dangling pointer will NEVER happen** because Rust compiler will make sure that if you have a reference to some data, the compiler will ensure that the data will not go out of scope before the reference to the data does.

```rust=

fn main() {

// This function cannot return because

// the variable s is dropped at the end of the function.

let reference_to_nothing = dangle();

}

fn dangle() -> &String {

let s = String::from("hello");

&s

}

```

Instead, you need to return an actual string.

```rust=

fn main() {

let string = no_dangle();

}

fn no_dangle() -> String {

let s = String::from("hello");

s

}

```

## slice

Another data type that does not have ownership is the slice. Slices let you reference a contiguous sequence of elements in a collection rather than the whole collection.

### String slices

When passing the pointer to a string into a function, it is better to pass a string slice (`&str`) rather than a reference to the string (`&String`), so as to [avoid layers of indirection](https://rust-unofficial.github.io/patterns/idioms/coercion-arguments.html).

```rust=

fn main() {

let s = String::from("hello world");

let hello = &s[0..5];

let world = &s[6..11];

}

```

- `s` owns the string.

- `world` is a reference pointing to the second word of the string.

### array slices

```rust=

#![allow(unused)]

fn main() {

let a = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5];

let slice = &a[1..3];

assert_eq!(slice, &[2, 3]);

}

```

### vector slices

```rust=

fn main() {

let v = vec![1, 2, 3, 4, 5];

let third: &i32 = &v[2];

println!("The third element is {}", third);

match v.get(2) {

Some(third) => println!("The third element is {}", third),

None => println!("There is no third element."),

}

}

```

**Credit to: [UPenn CIS 198](https://github.com/upenn-cis198)**