<style>

.reveal {

font-size: 24px;

}

.reveal section img {

background:none;

border:none;

box-shadow:none;

}

pre.graphviz {

box-shadow: none;

}

</style>

# Pipelining

*(AMH chapters 3-5, 11.1)*

Performance Engineering, Lecture 2

Sergey Slotin

May 7, 2022

---

## CPU pipeline

To execute *any* instruction, processors need to do a lot of preparatory work first:

- **fetch** a chunk of machine code from memory

- **decode** it and split it into instructions

- **execute** these instructions (which may involve doing some **memory** operations)

- **write** the results back into registers

This whole sequence of operations takes up to 15-20 CPU cycles even for something simple like `add`-ing two register-stored values together

----

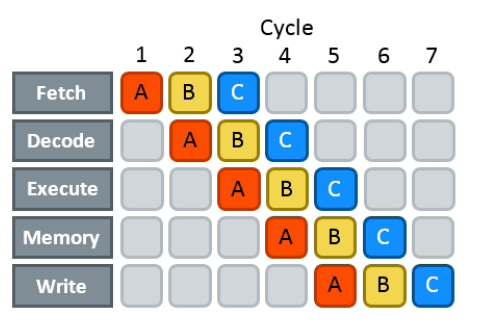

To hide this latency, modern CPUs use *pipelining*: after an instruction passes through the first stage, they start processing the next one right away, without waiting for the previous one to fully complete

Pipelining does not reduce *actual* latency but makes it seem like if it was composed of only the execution and memory stage

----

Real-world analogue: Henry Ford's assembly line

----

- To control for clock frequenccy, processor microarchitectures are benchmarked in terms of *cycles per instruction* (CPI)

- A perfectly pipelined CPU keeps every stage busy with some instruction, so that $\text{# of instructions} \to \infty,\; CPI \to 1$

- **Superscalar** processors have more than one of everything, in which case CPI could be less than 1 <!-- .element: class="fragment" data-fragment-index="1" -->

- The processor maintains a queue of pending instructions and starts executing them as soon as they are ready (*out-of-order execution*) <!-- .element: class="fragment" data-fragment-index="2" -->

---

## Hazards

*Pipeline hazards* are situations when the next instruction can't execute on the following clock cycle, causing a pipeline stall or "bubble"

- *Structural hazard*: two or more instructions need the same part of CPU

- *Data hazard*: need to wait for operands to be computed from a previous step

- *Control hazard*: the CPU can't tell which instructions it needs to execute next

----

- In *structural hazards*, you have to wait (usually one cycle) until the execution unit is ready; they are fundamental bottlenecks on performance and can’t be avoided

- In *data hazards*, you have to wait for the data to be computed (the latency of the critical path); data hazards are solved by shortening the critical pathr

- In *control hazards*, you have to flush the entire pipeline and start over, wasting 15-20 cycles; they are solved by removing branches or making them predictable so that the CPU can successfully *speculate* on what is going to be executed next

---

## The Cost of Branching

Let's simulate a completely unpredictable branch

```cpp

const int N = 1e6;

int a[N];

for (int i = 0; i < N; i++)

a[i] = rand() % 100;

// this part is benchmarked:

volatile int s; // to prevent vectorization, iteration interleaving, or other "cheating"

for (int i = 0; i < N; i++)

if (a[i] < 50)

s += a[i];

```

Measures ~14 CPU cycles per element

----

```nasm

mov rcx, -4000000

jmp body

counter:

add rcx, 4

jz finished ; "jump if rcx became zero"

body:

mov edx, dword ptr [rcx + a + 4000000]

cmp edx, 49

jg counter

add dword ptr [rsp + 12], edx

jmp counter

```

On a mispredict, we need to discard the pipeline (~19 cycles), perform a fetch and comparison (~5), per pipeline discard, and add `a[i]` to a volatile variable in case of a `<` branch (~4), bringing the expected value to roughly $(4 + 5 + 19) / 2 = 14$

----

Add a tweakable parameter `P`:

```cpp

for (int i = 0; i < N; i++)

if (a[i] < P)

s += a[i];

```

It sets the branch probability

----

----

- Most of the time, to do branch prediction, the CPU only needs a hardware statistics counter: if we historically took branch A more often than not, then it is probably more likely to be taken next

- Modern branch predictors are much smarter than that and can detect more complicated patterns

----

```cpp

for (int i = 0; i < N; i++)

a[i] = rand() % 100;

std::sort(a, a + n);

```

It runs 3.5x faster: using slightly over 4 cycles per element

(the average of the cost of pure `<` and `>=`)

----

```cpp

const int N = 1000;

// ...

```

Small arrays also at ~4 (it memorizes the entire array)

----

### Hinting likeliness

A new C++ feature:

```cpp

for (int i = 0; i < N; i++)

if (a[i] < P) [[likely]]

s += a[i];

```

When $P = 75$, it measures around ~7.3 cycles per element, while the original version without the hint needs ~8.3

----

Without hint:

```nasm

loop:

; ...

cmp edx, 49

jg loop

add dword ptr [rsp + 12], edx

jmp loop

```

With hint:

```nasm

body:

; ...

cmp edx, 49

jg loop

add dword ptr [rsp + 12], edx

loop:

; ...

jmp body

```

General idea: we want to have access to the next instructions as soon as possible

---

## Predication

The best way to deal with branches is to remove them, which we can do with *predication*, roughly equivalent to this algebraic trick:

$$

x = c \cdot a + (1 - c) \cdot b

$$

We eliminate control hazards at the cost of evaluating *both* branches

(and somehow "joining" them)

----

It takes ~7 cycles per element instead of the original ~14:

```cpp

for (int i = 0; i < N; i++)

s += (a[i] < 50) * a[i];

```

What does `(a[i] < 50) * a[i]` even do? There are no booleans in assembly

```nasm

mov ebx, eax ; t = x

sub ebx, 50 ; t -= 50 (underflow if x < 50, setting highest bit to 1)

sar ebx, 31 ; t >>= 31

imul eax, ebx ; x *= t

```

<!-- .element: class="fragment" data-fragment-index="1" -->

----

`((a[i] - 50) >> 31 - 1) & a[i]`

```nasm

mov ebx, eax ; t = x

sub ebx, 50 ; t -= 50

sar ebx, 31 ; t >>= 31

; imul eax, ebx ; x *= t

sub ebx, 1 ; t -= 1 (underflow if t = 0)

and eax, ebx ; x &= t (either 0 or all 1s)

```

This makes the whole sequence one cycle faster

(`imul` took 3 cycles, `sub` + `and` takes 2)

----

### Conditional move

Instead of arithmetic tricks, Clang uses a special `cmov` (“conditional move”) instruction that assigns a value based on a condition:

```nasm

mov ebx, 0 ; cmov doesn't support immediate values, so we need a zero register

cmp eax, 50

cmovge eax, ebx ; eax = (eax >= 50 ? eax : ebx=0)

```

The original code is actually closer to:

```cpp

for (int i = 0; i < N; i++)

s += (a[i] < 50 ? a[i] : 0);

```

----

75% is a commonly used heuristic in compilers

----

### Larger examples

- Zero strings

- Binary searching

- Data-parallel programming

```cpp

/* volatile */ int s = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < N; i++)

if (a[i] < 50)

s += a[i];

```

<!-- .element: class="fragment" data-fragment-index="1" -->

---

## Latency and Throughput

| Instruction | Latency | RThroughput |

|-------------|---------|:------------|

| `jmp` | - | 2 |

| `mov r, r` | - | 1/4 |

| `mov r, m` | 4 | 1/2 |

| `mov m, r` | 3 | 1 |

| `add` | 1 | 1/3 |

| `cmp` | 1 | 1/4 |

| `popcnt` | 1 | 1/4 |

| `mul` | 3 | 1 |

| `div` | 13-28 | 13-28 |

Zen 2 instruction tables

https://www.agner.org/optimize/instruction_tables.pdf

----

https://uops.info

----

For example, in Sandy Bridge family there are 6 execution ports:

* Ports 0, 1, 5 are for arithmetic and logic operations (ALU)

* Ports 2, 3 are for memory reads

* Port 4 is for memory write

You can lookup them up in instruction tables and find out which one is the bottleneck

----

Optimizing for latency is usually quite different from optimizing for throughput.

- Optimizing for latency, you need to make dependency chains shorter

- Optimizing for throughput, you need to remove pressure from bottlenecks

Nothing about "sum up all operations weighted by their costs" but throughput computing is ideologically somewhat closer to it

----

```cpp

int s = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < n; i++)

s += a[i];

```

(Pretend vectorization doesn't exist)

----

```cpp

int s = 0;

s += a[0];

s += a[1];

s += a[2];

s += a[3];

// ...

```

The next iteration depends on the previous one, so we can't execute more than one iteration per cycle despite `mov`/`add` having a throughput of two

----

```cpp

int s0 = 0, s1 = 0;

s0 += a[0];

s1 += a[1];

s0 += a[2];

s1 += a[3];

// ...

int s = s0 + s1;

```

We can now proceed in two concurrent "threads", doubling the throughput

---

## Profiling

1. Instrumentation <!-- .element: class="fragment" data-fragment-index="1" -->

2. Statistical profiling <!-- .element: class="fragment" data-fragment-index="2" -->

3. Simulation <!-- .element: class="fragment" data-fragment-index="3" -->

----

## Perf

---

## Case study: GCD

Euclid's algorithm finds the *greatest common divisor* (GCD):

$$

\gcd(a, b) = \max_{g: \; g|a \, \land \, g | b} g

$$

The algorithm recursively applies the formula and eventually converges to $b = 0$:

$$

\gcd(a, b) = \begin{cases}

a, & b = 0

\\ \gcd(b, a \bmod b), & b > 0

\end{cases}

$$

Works because if $g = \gcd(a, b)$ divides both $a$ and $b$, it should also divide $(a \bmod b = a - k \cdot b)$, but any larger divisor $d$ of $b$ will not

----

For random numbers under $10^9$, the average # of iterations is around 20 and the max is achieved for 433494437 and 701408733, the 43rd and 44th Fibonacci numbers

You can see bright blue lines at the proportions of the golden ratio

----

```cpp

int gcd(int a, int b) {

if (b == 0)

return a;

else

return gcd(b, a % b);

}

```

```cpp

int gcd(int a, int b) {

return (b ? gcd(b, a % b) : a);

}

```

<!-- .element: class="fragment" data-fragment-index="1" -->

```cpp

int gcd(int a, int b) {

while (b > 0) {

a %= b;

std::swap(a, b);

}

return a;

}

```

<!-- .element: class="fragment" data-fragment-index="2" -->

```cpp

int gcd(int a, int b) {

while (b) b ^= a ^= b ^= a %= b;

return a;

}

```

<!-- .element: class="fragment" data-fragment-index="3" -->

^Not even UB since C++17!

<!-- .element: class="fragment" data-fragment-index="3" -->

----

```nasm

; a = eax, b = edx

loop:

; modulo in assembly:

mov r8d, edx

cdq

idiv r8d

mov eax, r8d

; (a and b are already swapped now)

; continue until b is zero:

test edx, edx

jne loop

```

`perf` says it spends ~90% of the time on the `idiv` line: general integer division is slow

----

### Division by constants

When we divide one floating number $x$ by constant $y$, we can pre-calculate

$$

d \approx y^{-1}

$$

and then, during runtime, calculate

$$

x / y = x \cdot y^{-1} \approx x \cdot d

$$

This trick can be extended to integers:

<!-- .element: class="fragment" data-fragment-index="1" -->

```cpp

; input (rdi): x

; output (rax): x mod (m=1e9+7)

mov rax, rdi

movabs rdx, -8543223828751151131 ; load magic constant into a register

mul rdx ; perform multiplication

mov rax, rdx

shr rax, 29 ; binary shift of the result

```

<!-- .element: class="fragment" data-fragment-index="1" -->

But general division is slow, <!-- .element: class="fragment" data-fragment-index="1" --> **unless this is a divsion by two** <!-- .element: class="fragment" data-fragment-index="2" -->

----

### Binary GCD

1. $\gcd(0, b) = b$

(and symmetrically $\gcd(a, 0) = a$)

3. $\gcd(2a, 2b) = 2 \cdot \gcd(a, b)$

4. $\gcd(2a, b) = \gcd(a, b)$ if $b$ is odd

(and symmetrically $\gcd(a, b) = \gcd(a, 2b)$ if $a$ is odd)

6. $\gcd(a, b) = \gcd(|a − b|, \min(a, b))$, if $a$ and $b$ are both odd

$O(\log n)$: one of the arguments is divided by 2 at least every two iterations <!-- .element: class="fragment" data-fragment-index="1" -->

This algorithm is interesting because there is no division: the only arithmetic operations we need are binary shifts, comparisons, and subtractions — all taking just one cycle <!-- .element: class="fragment" data-fragment-index="2" -->

----

```cpp

int gcd(int a, int b) {

// base cases (1)

if (a == 0) return b;

if (b == 0) return a;

if (a == b) return a;

if (a % 2 == 0) {

if (b % 2 == 0) // a is even, b is even (2)

return 2 * gcd(a / 2, b / 2);

else // a is even, b is odd (3)

return gcd(a / 2, b);

} else {

if (b % 2 == 0) // a is odd, b is even (3)

return gcd(a, b / 2);

else // a is odd, b is odd (4)

return gcd(std::abs(a - b), std::min(a, b));

}

}

```

Two times **slower** than `std::gcd`, mainly due to all the branching and case matching

1. Replace all divisions by 2 with division by whichever highest power of 2 we can. This can be done with `__builtin_ctz` ("count trailing zeros"). Expected to decrease the number of iterations by almost a factor 2 because <!-- .element: class="fragment" data-fragment-index="1" --> $1 + \frac{1}{2} + \frac{1}{4} + \frac{1}{8} + \ldots \to 2$

2. Condition 2 can now only be true once: in the very beginning <!-- .element: class="fragment" data-fragment-index="2" -->

3. After we've entered condition 4 and applied its identity, $a$ will always be even and $b$ will always be odd, so we will be in condition 3. We can "de-evenize" $a$ right away and thus only loop from 4 to 3 until terminating by condition 1 <!-- .element: class="fragment" data-fragment-index="3" -->

----

```cpp

int gcd(int a, int b) {

if (a == 0) return b;

if (b == 0) return a;

int az = __builtin_ctz(a);

int bz = __builtin_ctz(b);

int shift = std::min(az, bz);

a >>= az, b >>= bz;

while (a != 0) {

int diff = a - b;

b = std::min(a, b);

a = std::abs(diff);

a >>= __builtin_ctz(a);

}

return b << shift;

}

```

It runs in 116ns, while `std::gcd` takes 198ns

----

```nasm

; a = edx, b = eax

loop:

mov ecx, edx

sub ecx, eax ; diff = a - b

cmp eax, edx

cmovg eax, edx ; b = min(a, b)

mov edx, ecx

neg edx

cmovs edx, ecx ; a = max(diff, -diff) = abs(diff)

tzcnt ecx, edx ; az = __builtin_ctz(a)

sarx edx, edx, ecx ; a >>= az

test edx, edx ; a != 0?

jne loop

```

----

Total time ~ length of dependency chain

We can calculate `ctz` using just `diff = a - b` because a negative number divisible by $2^k$ still has $k$ zeros at the end <!-- .element: class="fragment" data-fragment-index="1" -->

----

----

```cpp

int gcd(int a, int b) {

if (a == 0) return b;

if (b == 0) return a;

int az = __builtin_ctz(a);

int bz = __builtin_ctz(b);

int shift = std::min(az, bz);

b >>= bz;

while (a != 0) {

a >>= az;

int diff = b - a;

az = __builtin_ctz(diff);

b = std::min(a, b);

a = std::abs(diff);

}

return b << shift;

}

```

198ns → 116ns → 91ns. Our job here is done

{"metaMigratedAt":"2023-06-17T00:25:56.815Z","metaMigratedFrom":"YAML","title":"Pipelining","breaks":true,"slideOptions":"{\"theme\":\"white\"}","contributors":"[{\"id\":\"045b9308-fa89-4b5e-a7f0-d8e7d0b849fd\",\"add\":26312,\"del\":10452}]"}