<style>

.reveal {

font-size: 24px;

}

.reveal section img {

background:none;

border:none;

box-shadow:none;

}

pre.graphviz {

box-shadow: none;

}

</style>

# Instruction-Level Parallelism

High Performance Computing, Lecture 2

Sergey Slotin

Dec 20, 2020

---

## Recall: External Memory Model

* Memory is hierarchical, all reads are cached (we focus on ≤RAM today)

* Data is loaded in blocks (cache lines in our case, which are 64B)

* Cache misses dominate latency on higher levels (reading from RAM takes 100x more than arithmetic)

* ~~Everything is done sequentially~~ I/O operations may overlap! (within a limit) <!-- .element: class="fragment" data-fragment-index="1" -->

---

### Most of CPU isn't about computing

Hi-res shot of AMD "Zen" core die

----

It actually takes way more than one cycle to execute *anything*

----

## Pipelining

Modern CPUs attempt to keep every part of the processor busy with some instruction

$\text{# of instructions} \to \infty,\; CPI \to 1$

----

Real-world analogue: Henry Ford's assembly line

----

## Superscalar Processors

CPI could be less than 1 if we have more than one of everything

----

| Operation | Latency | $\frac{1}{throughput}$ |

| --------- | ------- |:------------ |

| MOV | 1 | 1/3 |

| JMP | 0 | 2 |

| ADD | 1 | 1/3 |

| SUM | 1 | 1/3 |

| CMP | 1 | 1/3 |

| POPCNT | 3 | 1 |

| MUL | 3 | 1 |

| DIV | 11-21 | 7-11 |

"Nehalem" (Intel i7) op tables

https://www.agner.org/optimize/instruction_tables.pdf

---

## Hazards

* Data hazard: waiting for an operand to be computed from a previous step

* Structural hazard: two instructions need the same part of CPU

* Control hazard: have to clear pipeline because of conditionals

Hazards create *bubbles*, or pipeline stalls

(i/o operations are "fire and forget", so they don't block execution)

<!-- .element: class="fragment" data-fragment-index="1" -->

----

## Branch Misprediction

Guessing the "wrong" side of "if" is costly because it interupts the pipeline

```cpp

// (assume "-O0")

for (int i = 0; i < n; i++)

a[i] = rand() % 256;

sort(a, a + n); // <- runs 6x (!!!) faster when sorted

int sum = 0;

for (int t = 0; t < 1000; t++) { // <- so that we are not bottlenecked by i/o (n < L1 cache size)

for (int i = 0; i < n; i++)

if (a[i] >= 128)

sum += a[i];

```

Minified code sample from [the most upvoted Stackoverflow answer ever](https://stackoverflow.com/questions/11227809/why-is-processing-a-sorted-array-faster-than-processing-an-unsorted-array)

----

### Mitigation Strategies

* Hardware (stats-based) branch predictor is built-in in CPUs,

* $\implies$ Replacing high-entropy `if`'s with predictable ones help

* You can replace conditional assignments with arithmetic:

`x = cond * a + (1 - cond) * b`

* This became a common pattern, so CPU manufacturers added `CMOV` op

that does `x = (cond ? a : b)` in one cycle

* *^This masking trick will be used a lot for SIMD and CUDA later*

* C++20 has added `[[likely]]` and `[[unlikely]]` attributes to provide hints:

```cpp

int f(int i) {

if (i < 0) [[unlikely]] {

return 0;

}

return 1;

}

```

---

## Branchy Binary Search

Contains an "if" that is impossible to predict better than a coin flip:

```cpp

int lower_bound(int x) {

int l = 0, r = n - 1;

while (l < r) {

int t = (l + r) / 2;

if (a[t] >= x)

r = t;

else

l = t + 1;

}

return a[l];

}

```

Also both temporal and spacial locality are terrible, but we address that later

----

This is actually how `std::lower_bound` works

```cpp

template<typename _ForwardIterator, typename _Tp, typename _Compare> _ForwardIterator

__lower_bound(_ForwardIterator __first, _ForwardIterator __last, const _Tp& __val, _Compare __comp) {

typedef typename iterator_traits<_ForwardIterator>::difference_type _DistanceType;

_DistanceType __len = std::distance(__first, __last);

while (__len > 0) {

_DistanceType __half = __len >> 1;

_ForwardIterator __middle = __first;

std::advance(__middle, __half);

if (__comp(__middle, __val)) {

__first = __middle;

++__first;

__len = __len - __half - 1;

}

else

__len = __half;

}

return __first;

}

```

[libstdc++ from GCC](https://github.com/gcc-mirror/gcc/blob/d9375e490072d1aae73a93949aa158fcd2a27018/libstdc%2B%2B-v3/include/bits/stl_algobase.h#L1023)

----

### Branch-Free Binary Search

It's not illegal: ternary operator is replaced with something like `CMOV`

```cpp

int lower_bound(int x) {

int base = 0, len = n;

while (len > 1) {

int half = len / 2;

base = (a[base + half] >= x ? base : base + half);

len -= half;

}

return a[base];

}

```

Hey, why not add prefetching? <!-- .element: class="fragment" data-fragment-index="1" -->

----

### Speculative Execution

* CPU: "hey, I'm probably going to wait ~100 more cycles for that memory fetch"

* "why don't I execute some of the later operations in the pipeline ahead of time?"

* "even if they won't be needed, I just discard them"

```cpp

bool cond = some_long_memory_operation();

if (cond)

do_this_fast_operation();

else

do_that_fast_operation();

```

*Implicit prefetching*: memory reads can be speculative too

$\implies$ reads will be pipelined anyway

<!-- .element: class="fragment" data-fragment-index="1" -->

(By the way, this is what Meltdown was all about)

<!-- .element: class="fragment" data-fragment-index="2" -->

---

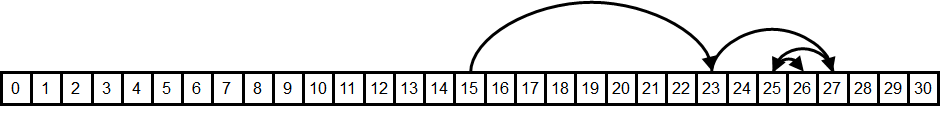

## Cache Locality Problems

* First ~10 queries may be cached (frequently accessed: temporal locality)

* Last 3-4 queries may be cached (may be in the same cache line: data locality)

* But that's it. Maybe store elements in a more cache-friendly way?

Access frequency heatmap if queries were random

---

## Eytzinger Layout

<!-- .slide: id="eytzinger" -->

<style>

#eytzinger {

font-size: 20px;

}

</style>

* **Michaël Eytzinger** is a 16th century Austrian nobleman known for his work on genealogy

* Ancestry mattered a lot back then, but writing down and storing that data was expensive

* He came up with *ahnentafel* (German for "ancestor table"), a system for displaying a person's direct ancestors compactly in a fixed sequence of ascent

*Thesaurus principum hac aetate in Europa viventium Cologne, 1590*

----

Ahnentafel works like this:

* First, the person theirself is listed as number 1

* Then, recursively, for each person numbered $k$:

* their father is listed as $2k$

* their mother is listed as $(2k+1)$

----

Here is the example for Paul I, the great-grandson of Peter I, the Great:

1. Paul I

2. Peter III (Paul’s father)

3. Catherine II (Paul’s mother)

4. Charles Frederick (Peter’s father, Paul’s paternal grandfather)

5. Anna Petrovna (Peter’s mother, Paul’s paternal grandmother)

6. Christian August (Catherine’s father, Paul’s maternal grandfather)

7. Johanna Elisabeth (Catherine’s mother, Paul’s maternal grandmother)

Apart from being compact, it has some nice properties, for example:

<!-- .element: class="fragment" data-fragment-index="1" -->

* Ancestors are sorted by "distance" from the first person <!-- .element: class="fragment" data-fragment-index="2" -->

* All even-numbered persons $>1$ are male and all odd-numbered are female <!-- .element: class="fragment" data-fragment-index="3" -->

* You can find the number of an ancestor knowing their descendants' genders <!-- .element: class="fragment" data-fragment-index="4" -->

Example: Peter the Great's bloodline is:

Paul I → Peter III → Anna Petrovna → Peter the Great,

so his number should be $((1 \times 2) \times 2 + 1) \times 2 = 10$

<!-- .element: class="fragment" data-fragment-index="5" -->

---

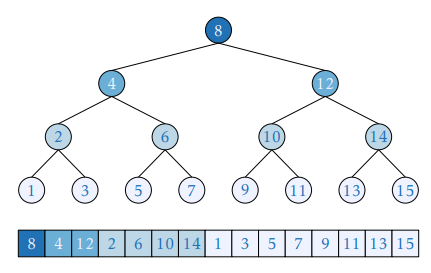

## Back to Computer Science

This enumeration has been widely used for implicit ("pointer-free") implementations of heaps, segment trees, and other binary tree structures

This is how this layout looks when applied to binary search

Important note: *it begins with 1 and not 0*

<!-- .element: class="fragment" data-fragment-index="1" -->

----

Temporary locality is way better

----

## Construction

You could build it by traversing and remapping the original search tree

```cpp

const int n = 1e5;

int a[n], b[n+1];

int eytzinger(int k = 1) {

static int i = 0; // <- carefull when invoking multiple times

if (k <= n) {

eytzinger(2 * k);

b[k] = a[i++];

eytzinger(2 * k + 1);

}

}

```

Notice that the order in which we exit nodes is just array elements themself,

so we can just copy elements on exit and not calculate $l$ and $r$

---

## Searching

Same as in binary search, but instead of ranges start with $k=1$ and execute:

* $k := 2k$ if we need to go left

* $k := 2k + 1$ if we need to go right

The only problem arises when we need to restore the index of the resulting element,

as $k$ may end up not pointing to a leaf node

<!-- .element: class="fragment" data-fragment-index="1" -->

----

<!-- .slide: id="searching" -->

<style>

#searching pre {

width: 410px;

}

</style>

Example: querying array of of $[1, …, 8]$ for the lower bound of $x=4$

(we end up with $k=11$ which is not even a valid index)

```

array: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

eytzinger: 4 2 5 1 6 3 7 8

1st range: --------------- k := 1

2nd range: ------- k := 2*k (=2)

3rd range: --- k := 2*k + 1 (=5)

4th range: - k := 2*k + 1 (=11)

```

* Unless the answer is the last element, we compare $x$ against it at some point

* After we learn that $ans \geq x$, we start comparing $x$ against elements to the left

* All these comparisons will evaluate true ("leading to the right")

* $\implies$ We need to "cancel" some number of riht turns

<!-- .element: class="fragment" data-fragment-index="1" -->

----

* The right turns are recorded in the binary notation of $k$ as 1-bits

* We just need to find the number of trailing ones in the binary notation

and right-shift $k$ by exactly that amount

* To do it, invert the bits of $k$ and use "find first set" instruction on it

```cpp

int search(int x) {

int k = 1;

while (k <= n) {

if (b[k] >= x)

k = 2 * k;

else

k = 2 * k + 1;

}

k >>= __builtin_ffs(~k);

return b[k];

}

```

Note that $k$ will be zero if binary search returned no result

(all turns were right-turns and got canceled)

---

## Optimization: Branch-Free

Inner "if-else":

```cpp

while (k <= n) {

if (b[k] >= x)

k = 2 * k;

else

k = 2 * k + 1;

}

```

...can be easily rewritten to:

```cpp

while (k <= n)

k = 2 * k + (b[k] < x);

```

Apart from mitigating branch mispredictions,

it also directly saves us a few arithmetic instructions

---

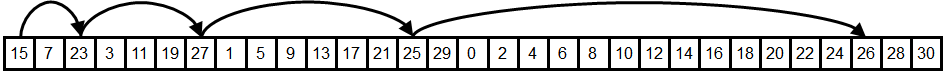

## Optimization: Prefetching

Let me just dump this line of code and then explain why it works so well:

```cpp

const int block_size = 64 / 4; // the number of elements that fit into one cache line (16 for ints)

while (k <= n) {

__builtin_prefetch(b + k * block_size);

k = 2 * k + (b[k] < x);

}

```

What is happening? What is $k \cdot B$?

It is $k$'s grand-grand-grandfather!

<!-- .element: class="fragment" data-fragment-index="1" -->

----

* When we fetch $k * B$, *if it is on the beginnigng of a cache line*,

we also cache next $B$ elements, all of which happe to be our grand-grand-grandfathers too

* As i/o is pipelined, we are always prefetching 4 levels in advance

* We are trading off bandwidth for latency <!-- .element: class="fragment" data-fragment-index="1" -->

*Latency-bandwith product* must be $\geq 4$ to do that (on most computers, it is)

<!-- .element: class="fragment" data-fragment-index="1" -->

----

### Memory Alignment

Minor detail: for all this to work we need to start at 2nd position of a cache line

```cpp

alignas(64) int b[n+1];

```

This way, we also fetch all 4 first levels (1+2+4+8=15 elements) on the first read

---

## Final Implementation

```cpp

const int n = (1<<20);

const int block_size = 16; // = 64 / 4 = cache_line_size / sizeof(int)

alignas(64) int a[n], b[n+1];

int eytzinger(int k = 1) {

static int i = 0;

if (k <= n) {

eytzinger(2 * k);

b[k] = a[i++];

eytzinger(2 * k + 1);

}

}

int search(int x) {

int k = 1;

while (k <= n) {

__builtin_prefetch(b + k * block_size);

k = 2 * k + (b[k] < x);

}

k >>= __builtin_ffs(~k);

return k;

}

```

(yes, it's just 15 lines of code)

---

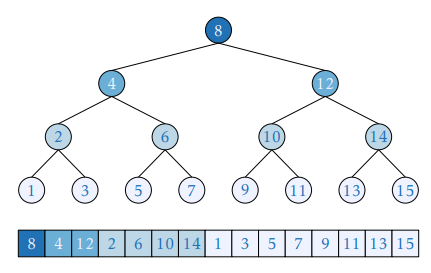

## B-trees

* Idea: store $B$ keys in each "node", where $B$ is exactly the block size

* In external memory model, doing $B$ comparisons costs the same as doing one

* This allows branching factor of $(B+1)$ instead of $2$

----

### Layout

Exact layout of blocks doesn't really matter, because we fetch the whole block anyway

```cpp

const int nblocks = (n + B - 1) / B;

alignas(64) int btree[nblocks][B];

// helper function to get i-th child of node k

int go(int k, int i) {

return k * (B + 1) + i + 1;

}

```

----

### Building

Very similar to `eytzinger`, just generalized over $B+1$ children:

```cpp

void build(int k = 0) {

static int t = 0;

if (k < nblocks) {

for (int i = 0; i < B; i++) {

build(go(k, i));

btree[k][i] = (t < n ? a[t++] : INF);

}

build(go(k, B));

}

}

```

----

### Searching

```cpp

int search(int x) {

int k = 0, res = INF;

start: // the only justified usage of the goto statement

// as doing otherwise would add extra inefficiency and more code

while (k < nblocks) {

for (int i = 0; i < B; i++) {

if (btree[k][i] >= x) {

res = btree[k][i];

k = go(k, i);

goto start;

}

}

k = go(k, B);

}

return res;

}

```

---

## Single Instruciton, Multiple Data

Remember talk about superscalar execution?

SIMD is like if we had multiple ALUs:

As the name suggests, it allows performing the same operation on multiple data points

(blocks of 128, 256 or 512 bits)

*This is the sole topic of the next lecture, stay tuned*

<!-- .element: class="fragment" data-fragment-index="1" -->

----

Let's rewrite comparison part in a data-parallel fashion:

```cpp

int mask = (1 << B);

for (int i = 0; i < B; i++)

mask |= (btree[k][i] >= x) << i;

int i = __builtin_ffs(mask) - 1;

// now i is the number of the correct child node

```

Here is how it looks with SIMD:

<!-- .element: class="fragment" data-fragment-index="1" -->

```cpp

// SIMD vector type names are weird and tedious to type, so we define an alias

typedef __m256i reg;

// somewhere in the beginning of search loop:

reg x_vec = _mm256_set1_epi32(x);

int cmp(reg x_vec, int* y_ptr) {

reg y_vec = _mm256_load_si256((reg*) y_ptr);

reg mask = _mm256_cmpgt_epi32(x_vec, y_vec);

return _mm256_movemask_ps((__m256) mask);

}

```

<!-- .element: class="fragment" data-fragment-index="1" -->

----

## Final Version

```cpp

int search(int x) {

int k = 0, res = INF;

reg x_vec = _mm256_set1_epi32(x);

while (k < nblocks) {

int mask = ~(

cmp(x_vec, &btree[k][0]) +

(cmp(x_vec, &btree[k][8]) << 8)

);

int i = __builtin_ffs(mask) - 1;

if (i < B)

res = btree[k][i];

k = go(k, i);

}

return res;

}

```

Cache line size is twice as large as SIMD registers on most CPUs (512 vs 256),

so we call `cmp` twice and blend results

---

## Analysis

* Assume all arithmetic is free, only consider i/o

* The Eytzinger binary search is supposed to be $4$ times faster if compute didn't matter, as it reads are ~4 times faster on average <!-- .element: class="fragment" data-fragment-index="1" -->

* The B-tree makes $\frac{\log_{17} n}{\log_2 n} = \frac{\log n}{\log 17} \frac{\log 2}{\log n} = \frac{\log 2}{\log 17} \approx 0.245$ memory access per each request of binary search, i. e. it needs ~4 times less cache lines to fetch <!-- .element: class="fragment" data-fragment-index="2" -->

* So when bandwidth is not a bottleneck, they are more or less equal <!-- .element: class="fragment" data-fragment-index="3" -->

---

## Segment Trees

* Static tree data structure used for storing information about array segments

* Popular in competitive programming, very rarely used in real life

* Built recursively: build a tree for left and right halves and merge results to get root

* Many different implementations possible

----

### Pointer-Based

* Actually really good in terms of SWE practices, but terrible in terms of performance

* Pointer chasing, 4 unnecessary metadata fields, recursion, branching

```cpp

struct segtree {

int lb, rb; // left and right borders of this segment

int sum = 0; // sum on this segment

segtree *l = 0, *r = 0;

segtree(int _lb, int _rb) {

lb = _lb, rb = _rb;

if (lb + 1 < rb) {

int t = (lb + rb) / 2;

l = new segtree(lb, t);

r = new segtree(t, rb);

}

}

void add(int k, int x) {

sum += x;

if (l) {

if (k < l->rb) l->add(k, x);

else r->add(k, x);

}

}

int get_sum(int lq, int rq) {

if (lb >= lq && rb <= rq) return sum;

if (max(lb, lq) >= min(rb, rq)) return 0;

return l->get_sum(lq, rq) + r->get_sum(lq, rq);

}

};

```

https://algorithmica.org/ru/segtree

----

### Implicit (Recursive)

* Eytzinger-like layout: $2k$ is the left child and $2k+1$ is the right child

* Wasted memory, recursion, branching

```cpp

int n, t[4 * MAXN];

void build(int a[], int v, int tl, int tr) {

if (tl == tr)

t[v] = a[tl];

else {

int tm = (tl + tr) / 2;

build (a, v*2, tl, tm);

build (a, v*2+1, tm+1, tr);

t[v] = t[v*2] + t[v*2+1];

}

}

int sum(int v, int tl, int tr, int l, int r) {

if (l > r)

return 0;

if (l == tl && r == tr)

return t[v];

int tm = (tl + tr) / 2;

return sum (v*2, tl, tm, l, min(r,tm))

+ sum (v*2+1, tm+1, tr, max(l,tm+1), r);

}

```

http://e-maxx.ru/algo/segment_tree

----

### Implicit (Iterative)

* Different layout: leaf nodes are numbered $n$ to $(2n - 1)$, "parent" is $\lfloor k/2 \rfloor$

* Minimum possible amount of memory

* Fully iterative and no branching (pipelinize-able reads!)

```cpp

int n, t[2*maxn];

void build() {

for (int i = n-1; i > 0; i--)

t[i] = max(t[i<<1], t[i<<1|1]);

}

void upd(int k, int x) {

k += n;

t[k] = x;

while (k > 1) {

t[k>>1] = max(t[k], t[k^1]);

k >>= 1;

}

}

int rmq(int l, int r) {

int ans = 0;

l += n, r += n;

while (l <= r) {

if (l&1) ans = max(ans, t[l++]);

if (!(r&1)) ans = max(ans, t[r--]);

l >>= 1, r >>= 1;

}

return ans;

}

```

https://codeforces.com/blog/entry/18051

---

## Fenwick trees

* Structure used to calculate prefix sums and similar operations

* Defined as array $t_i = \sum_{k=f(i)}^i a_k$ where $f$ is any function for which $f(i) \leq i$

* If $f$ is "remove last bit" (`x -= x & -x`),

then both query and update would only require updating $O(\log n)$ different $t$'s

```cpp

int t[maxn];

// calculate sum on prefix:

int sum(int r) {

int res = 0;

for (; r > 0; r -= r & -r)

res += t[r];

return res;

}

// how you can use it to calculate sums on subsegments:

int sum (int l, int r) {

return sum(r) - sum(l-1);

}

// updates necessary t's:

void add(int k, int x) {

for (; k <= n; k += k & -k)

t[k] += x;

}

```

Can't be more optimal because of pipelining and implicit prefetching

---

## Next week

* Will learn how to use SIMD instructions (SSE, AVX)

* Data parallel programming, loop unrolling, memory alignment, autovectorization

* Teaser: going to achieve 5-10x speedups on simple loops

Additional reading:

* [Text version of this lecture](htpp://algorithmica.org/en/eytzinger) by me

* [Modern Microprocessors: a 90-minute guide](http://www.lighterra.com/papers/modernmicroprocessors/) by Patterson

* [Array layouts for comparison-based searching](https://arxiv.org/pdf/1509.05053.pdf) by Khuong and Morin

{"metaMigratedAt":"2023-06-15T17:21:07.859Z","metaMigratedFrom":"YAML","title":"Instruction-Level Parallelism","breaks":true,"slideOptions":"{\"theme\":\"white\"}","contributors":"[{\"id\":\"045b9308-fa89-4b5e-a7f0-d8e7d0b849fd\",\"add\":33805,\"del\":11991}]"}