# Falcon Signatures: A Post Quantum Signature Candidate for Ethereum

## Overview

Falcon signatures are lattice-based, hash-and-sign-type signatures which are proven to be classically and importantly quantum-secure.

There have been recent proposals to use Falcon in Ethereum for signing, as a post-quantum secure signature alternative. The recent [Beam chain](https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lRqnFrqpq4k) proposal is looking at Falcon as a candidate for attestation signatures in the consensus layer of Ethereum.

This article gives a brief introduction to Falcon and its internals. It also includes the advantages and disadvantages of Falcon in the context of Ethereum.

## Introduction

Falcon (Fast Fourier Lattice-based Compact signatures over NTRU) is based on the GPV (Gentry Peikert Vaikuntanathan) framework for lattice-based signature schemes. Falcon was submitted to NIST in 2017. It uses Fast Fourier Sampling as the trapdoor sampler and NTRU lattices as the lattice structure.

Falcon = GPV framework + NTRU lattices + Fast Fourier Sampling

One major challenge in post-quantum cryptography is the typically large size of keys and signatures compared to classical schemes.

The main goal while creating Falcon was to minimize the size of the public key and signatures. It was designed with compactness in mind.

```

Minimize:

|pk| + |sig| = (bitsize of public key) + (bitsize of signature)

```

## Basics

### Finite Fields

In Falcon, computations are performed in the ring $\mathbb{Z}_q[x]/(\phi)$, where $\phi = x^n + 1$ and $q$ is a prime modulus. This ring consists of polynomials with coefficients in the finite field $\mathbb{Z}_q$, reduced modulo the polynomial $\phi$.

Let us consider an example for polynomial addition over the integer field modulo $q$, say we have two polynomials $p(x) = x ^ 3 + 4$ and $q(x) = 5x^2 + 3$. Suppose we operate in the finite field $\mathbb{Z}_3$, i.e. calculations are modulo $3$.

Then,

$$

p(x) + q(x) = (x^3 + 5x^2 + 7)

= x^3 + 2x^2 + 1

$$

That is, each coefficient of the polynomial is added modulo 3.

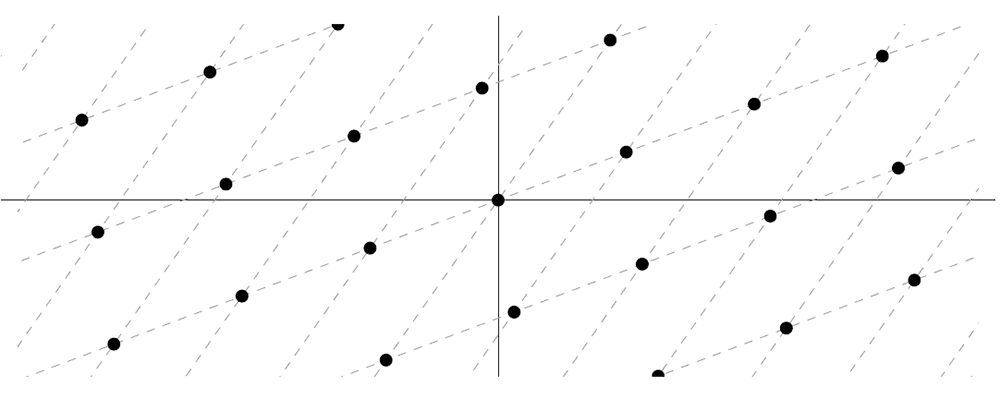

### Lattice Theory

A lattice is a regular grid of points in an n-dimensional space.

Mathematically, it is defined as integer linear combinations of a basis of vectors ${\{b_1, b_2, \dots b_k}\}$, where $b_i$ belongs to $\mathbb{R}^n$.

$$

v = c_1b_1 + c_2b_2 + \dots c_kb_k; \ c_i \in \mathbb{Z}, \ b_i \in \mathbb{R} ^ n

$$

$k$ is called the rank of the lattice. A lattice is called full-rank when $k = n$.

### Cryptography in Lattices

In every cryptographic scheme, there is an underlying "hard" problem. For example, RSA relies on the hardness of integer factorization, while ECDSA relies on the hardness of the Discrete Logarithm Problem. It is called "hard" because there is no known efficient classical algorithm that solves the problem.

The discrete-log problem, which is the basis of a lot of cryptographic schemes used today is a "hard" problem classically, but with a sufficiently-powerful quantum computer, one can solve it, thus breaking the cryptographic schemes.

Ethereum currently uses Elliptic curve cryptography (ECDSA) for signatures, which is based on the Discrete Log problem. If a capable quantum computer is constructed, Ethereum's network would be vulnerable to attackers.

As an alternative, lattice cryptography is being looked into, and it is promising. Problems such as Closest Vector Problem (CVP) and Short Integer Solution (SIS) are known "hard" problems even for quantum computers.

These form the basis of Falcon's security scheme.

#### Closest Vector Problem (CVP)

Given a random point, it is hard to find a lattice point closest to the random point using a random basis.

If you have access to a short basis (which is usually the private key in such schemes), it is easy to find a short vector closest to said point efficiently.

The public key is usually a long basis, which makes it hard for a malicious attacker to find a short vector closest to the point, thus making it hard to forge a signature.

#### Short Integer Solution (SIS)

Given a random matrix $A \in \mathbb{Z}_q ^ {n \times m}$ (meaning a matrix with $n$-rows and $m$-columns whose entries are integers modulo $q$), find a non-zero integer vector $x \in \mathbb{Z} ^ m$ such that $A.x = 0 \ (mod \ q)$ and $||x||$ is small. This is hard (NP-hard in average cases).

Falcon is based on the GPV-framework for lattice-based signatures, which rely on solving a version of SIS with a secret trapdoor (the private key).

### NTRU Lattices

In Falcon operations are done in the cyclotomic ring $\mathbb{Z}_q / (f(x))$, where $f(x) = x ^n + 1$, $n$ is a power of 2.

The meaning of this is that a polynomial $p(x) = a_kx^k + a_{k-1}x^{k-1} + ... + a_0$ in this space has degree k < n and integer coefficients modulo q ($a_i \in \mathbb{Z}_q$).

For example, suppose we work in the ring $\mathbb{Z}_q / f(x)$, where $q = 3$ and $f(x) = x ^ 4 + 1$.

Suppose we have a polynomial $p(x) = 5x ^ 4 + x + 10$. Since the degree of $p$ is $≥ 4$, we divide $p$ by $f$ and take the remainder.

$$

p(x) = (5x^4 + 5) + (x + 5)

= 5(x^4 + 1) + (x+5)

$$

Therefore we get $p(x) = x + 5 \ (mod f)$.

Now, we take the coefficients modulo $q$, i.e. 3 here.

$$

\therefore \ p(x) = x + 2 \ {\text { in }} \ \mathbb{Z}_q / f(x)

$$

The main reasons for using NTRU lattices in Falcon are:

- Compactness

- Reduces public key size by a factor of $O(n)$

- Speeds up some computations by a factor of atleast $O(n/log \ n)$

- Public key can be reduced to a single polynomial $h(x) \in \mathbb{Z}_q[x]$ of degree at most $n - 1$

## Falcon

### GPV Framework

At a high level, the framework works as follows:

- The public key contains a full-rank matrix $A ∈ \mathbb{Z}^{n×m}_q$ (with $m > n$) generating a lattice $Λ$.

- The private key contains a matrix $B ∈ \mathbb{Z}^{m×m}_

q$ generating $Λ^⊥_q$ , where $Λ^⊥_q$ denotes the lattice orthogonal to $Λ$ modulo $q$.

- Given a message $m$, a signature of $m$ is a short value $s ∈\mathbb{Z}^m_q$ such that $sA^t = H(m)$ ($t$ is the transpose of the matrix), where $H :\{0, 1\}^* → \mathbb{Z}^n_q$ is a hash function. Given $A$, verifying that $s$ is a valid signature is straightforward: it only requires to check that $s$ is indeed short and verifies $sA^t = H(m)$.

- Computing a valid signature is more delicate. First, a preimage $c_0 ∈ \mathbb{Z}^m_q$ is computed, which verifies $c_0A^t = H(m)$. As $c_0$ is not required to be short and $m ≥ n$, this is simply done via standard linear algebra. $B$ is then used in order to compute a vector $v ∈ Λ^⊥_q$ **close to** $c_0$ (**CVP**). The difference $s = c_0 − v$ is a valid signature: indeed, $sA^t = c_0A^t − vA^t = c − 0 = H(m)$, and if $c_0$ and $v$ are close enough, then $s$ is short.

In Falcon, two different signatures $s$ and $s'$ of a same hash $H(m)$ can never be made public at the same time. Doing so will break the security proof (it allows attackers to recover the private key). Therefore, a random salt $r: \{0,1\}^{320}$ (a 320-bit random number) is generated and prepended to a message before hashing it.

$$

H(r||m)

$$

### NTRU Lattices

Let $\phi = x ^ n + 1$, $n$ is a power of 2. A set of NTRU secrets consist of the polynomials $f, g, F, G \in \mathbb{Z}[x]/(\phi)$ which follow the NTRU equation:

$$

fG - gF = q \ \ mod \phi \ \ ;

q \in \mathbb{Z}, q \not= 0

$$

If $f$ is invertible modulo $q$, we can define the polynomial $h ← g · f ^ {−1} \ mod \ q$.

Normally, $h$ is the public key and $f,g,F,G$ are the secret keys.

Matrices $\begin{bmatrix}1 & h \\ 0& q\end{bmatrix}$ and $\begin{bmatrix}f & g \\ F& G \end{bmatrix}$ generate the same lattice but the first matrix contains two large polynomials $h$ and $q$ (which hide the secret basis) whereas the second matrix contains small polynomials, allowing signature generation to be fast.

### NTRU with the GPV framework

- The public basis is $A = \begin{bmatrix} 1 & h^* \end{bmatrix}$.

- The secret basis is $B = \begin{bmatrix}g & -f \\ G& -F \end{bmatrix}$. One can check that $B \times A^* = 0 \ mod \ q$ using the NTRU equation.

- The signature of a message $m$ consists of a salt $r$ plus a pair of polynomials $(s_1, s_2)$ such that $s_1 + s_2h = H(r || m)$.

### Trapdoor Sampler

A trapdoor sampler takes as input a matrix $A$, a trapdoor $T$ (the secret key), a target $c$ and outputs a short vector $s$ such that $s^tA = c \ mod q$.

Falcon uses a randomized version of fast Fourier nearest plane algorithm, introduced by Léo Ducas and Thomas Prest, due to its speed and NTRU-friendliness. The algorithm is similar to Fast Fourier transform (it recursively tries to find the nearest plane to the target) and thus the name.

## Signature Generation and Verification procedure

Now let's dive into what exactly is the procedure for generating and verifying signatures in Falcon. The Falcon specification is quite math-heavy so I'll try to give a simple overview of some of the techniques used. The official [Falcon specification](https://falcon-sign.info/falcon.pdf) uses the following parameters:

- Computations are done modulo a polynomial of the form $\phi (x) = x^n + 1$, where $n$ is 512 or 1024.

- Falcon uses $q$ = 12289, thus the field for coefficients becomes $\mathbb{Z}_{12289}$, which is a finite field.

- The polynomials used can be represented as matrices. An $n$-degree polynomial is written as an $n \times n$ matrix, with the rows being $x_if \ mod ϕ$, where $f(x)$ is the $n$-degree polynomial. For example, consider $n=3$ and $ϕ(x)=x^3+1$.

Take $f(x)=f_0+f_1x+f_2x^2$.

Then the matrix representation of $fmod ϕ$ would be:

$$

\begin {bmatrix} f_0 & f_1 & f_2 \\ -f_2 & f_0 & f_1 \\ -f_1 & -f_2 & f_0\end{bmatrix}

$$

Each row is a cyclic shift of the coefficients, with some minus signs coming from the fact that $x^3≡−1 \ mod (x^3+1)$.

### Signature Generation

Given a private key $s_k$ and a message $m$, the signer signs as follows:

1. A random salt $r$ is generated uniformly in $\{0, 1\}^{320}$. The concatenated string $(r||m)$ is then hashed to a point $c ∈ \mathbb{Z}_q[x]/(ϕ)$ as specified by a HashToPoint algorithm. The HashToPoint algorithm uses SHAKE-256, an extendable-output hash function. The algorithm generates a polynomial (a point in the lattice) in $\mathbb{Z}_q[x]/(ϕ)$.

2. A preimage $t$ of $c$ is computed, and is then given as input to the fast Fourier sampling algorithm, which outputs two short polynomials $s_1, s_2 ∈ \mathbb{Z}[x]/(ϕ)$ such that $s_1 + s_2h = c \ mod \ q$.

4. $s_2$ is encoded (compressed) to a bitstring $s$.

5. The signature consists of the pair $(r, s)$.

The signature generation process utilizes a structure called the Falcon Tree, which is a data structure used for speeding up the Fast Fourier sampling process. It is formed during key generation, and involves splitting key matrices into smaller matrices so that the algorithm can be implemented recursively and more efficiently.

### Signature Verification

The signature verification procedure is much simpler than key pair generation or signature generation. Given a public key $p_k = h$, a message $m$, a signature $sig = (r,s)$ and an acceptance bound $⌊β^2⌋$, the verifier uses $p_k$ to verify that $sig$ is a valid signature for the message $m$:

1. The value $r$ (called “the salt”) and the message $m$ are concatenated to a string $(r||m)$ which is hashed to a polynomial $c ∈ \mathbb{Z}_q[x]/(ϕ)$ using the HashToPoint algorithm mentioned above.

2. $s$ is decoded (decompressed) to a polynomial $s_2 ∈ \mathbb{Z}[x]/(ϕ)$.

3. The value $s_1 = c − s_2h \ mod \ q$ is computed.

4. If $||(s_1, s_2)||^2 ≤ ⌊β^2⌋$ (signature is short), then the signature is accepted as valid. Otherwise, it is rejected.

## Advantages and Disadvantages of Falcon

### Advantages

- **Compactness**: Falcon was designed with compactness as the main criterion.

- **Fast signature generation and verification**: The signature algorithm can perform more than 1000 signatures per second on a moderately-powered computer.

- **Easy signature verification**: The verification is very simple: essentially, one just needs to compute $[H(r∥m) − s_2h] \ mod \ q$, which boils down to just a few computations.

### Disadvantages

- **Complex Implementation**: The Falcon specification is non-trivial to understand and implement.

- **Floating point arithmetic**: The signing procedure of Falcon uses 53 bits of decimal precision, which may be a problem for hardware-constrained devices, and may pose a challenge with blockchain systems, where decimals are not inbuilt and have to be handled separately.

### Falcon and Ethereum

There are a couple of reasons why Falcon is being considered as a post-quantum cryptographic candidate for the Ethereum network.

- One of the reasons why Falcon is a promising candidate is because of the size of the public key and signature. Falcon maintains the same security guarantees as other lattice-based cryptographic schemes while having a public key and signature size significantly smaller than its competitors. For Ethereum, it could mean being able to have more attestations for a block, thus being able to host more validators (about 5 times more).

- Falcon signature aggregation, either with code-based SNARKs or with lattice-based SNARKs is being considered to replace BLS aggregation. Code-based SNARKs provide impressive prover and verifier efficiency. Lattice-based SNARKs give very small aggregated signature sizes, yet have verification time linear in the witness size. A best of both world's solution would be optimal for Ethereum.

## Conclusion

Falcon is a powerful post-quantum signature candidate with compact signatures and proven security. However, its implementation and complexity require careful engineering in production systems like Ethereum.

Only more research will be able to tell if Falcon is a good replacement for Ethereum's current signatures schemes or if some other quantum-secure signature scheme will prevail.

### Resources:

Here are some of the resources I used to understand Falcon:

- [Falcon's specification](https://falcon-sign.info/falcon.pdf)

- [Beam Call #2 (Post-Quantum Cryptography)](https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BtYb_guRq78)

- [Falcon as an Ethereum Transaction Signature - ethresear.ch](https://ethresear.ch/t/falcon-as-an-ethereum-transaction-signature-the-good-the-bad-and-the-gnarly/21512)